By Chris Dier

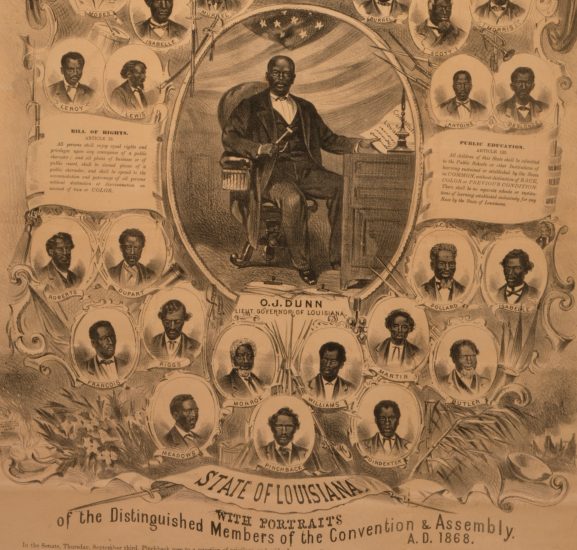

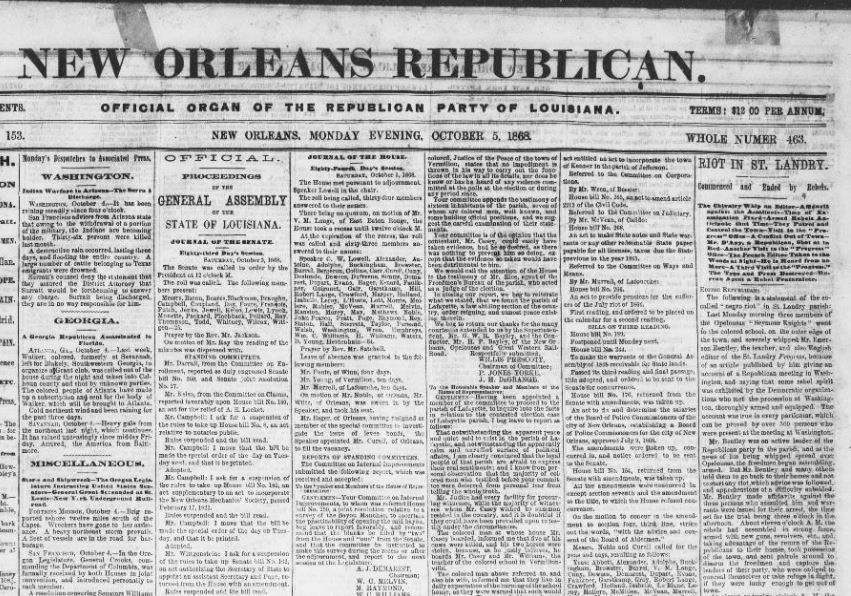

Portion of illustration depicting Oscar Dunn of Louisiana, the first African American elected lieutenant governor of any state, and other legislators. Source: Library of Congress (Click image for more info.)

Following the Civil War, as freedmen gained the right to vote, white Democrats of the St. Bernard Parish in Louisiana (and throughout the South) were afraid of losing their majority and thus their power to thwart Reconstruction efforts.

In late October of 1868, armed groups of white men mobilized to suppress the recently emancipated voters in the hopes of regaining their way of life turned upside down by the Civil War and Reconstruction. It was just days before the presidential election between Ulysses S. Grant and Horatio Seymour, which would decide the fate of Reconstruction in the South.

On October 25, 1868, the first blood spilled of the St. Bernard Parish Massacre.

Days later, freedman Louis Wilson was struck down from his horse and thrown in a makeshift prison by a group of white, Democratic vigilantes.

Freedpeople were dragged from their homes and murdered in cold blood. The reported numbers of those killed varies from 35 to over 100. Many who escaped death did so by fleeing to the cane fields, where they hid for days.

Over 60 freedpeople were arrested after the atrocities while not a single perpetrator was questioned. While the gruesome nature of the tragedy was swept under the rug, the implications reverberated throughout the South for generations.

Grant received only one vote in St. Bernard Parish as Seymour swept the state. As historian John C. Rodrigue puts it,

Republicans captured the presidency in 1868, but white terror carried the day in Louisiana.

Despite the federal investigation, no one was arrested for the killing of the freed people. Black survivors identified white neighbors as their assailants, but no justice was sought. Instead, more than 60 freed people were arrested by local authorities and vigilantes for the killing of Pablo San Feliu.

Over time, the massacre faded into obscurity. To this day, its only physical reminder is the tombstone of Pablo San Feliu, located in St. Bernard Cemetery, which reads:

Assassinated by Slaves

Incited by Carpetbag Rule

Died Oct. 1869

The inaccuracies on San Feliu’s tombstone misrepresent the circumstances surrounding his death. The incorrect date suggests that it was erected a significant amount of time after the massacre, perhaps memorializing his death as if he were a martyr. The engraver referred to the freed people as “slaves.” Most importantly, by placing blame on carpetbaggers, the derogatory term applied to Northerners and other outsiders who had migrated to the South during Reconstruction, the inscription implies that San Feliu was an innocent murder victim. Continue reading.

This entry was prepared by St. Bernard Parish high school history teacher Chris Dier on the 150th anniversary of the massacre. Dier is the author of “Unraveling a Forgotten Massacre in My Louisiana Hometown: A History Teacher Discovers a Racially Driven Rampage That Still Haunts His Students’ Lives” (Zócalo Public Square) and The 1868 St. Bernard Parish Massacre: Blood in the Cane Fields (History Press).

Chris Dier, an eight-year veteran in the St. Bernard Public Schools, researched and wrote about the St. Bernard Parish Massacre because,

Chris Dier, an eight-year veteran in the St. Bernard Public Schools, researched and wrote about the St. Bernard Parish Massacre because,

Not only did I live in the very parish where the massacre took place, but the surnames of the assailants and the victims matched those of some of my students, both Black and white, who worked together, played sports together, and shared lunches. My focus is to have students think critically about the past and its relevance to their own lives. It’s their history. They should own it.

Dier credits his passion for local history to his mother Lynne Dier, who taught high school history in St. Bernard for four decades.

Learn more in the Zinn Education Project national report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction,” and find teaching resources on Reconstruction below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn