Sarah Keys

At just 22 years old, on Aug. 1, 1952, Sarah Keys Evans refused to give up her seat on a state-to-state charter bus, prompting the landmark court case, Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company, in which the Interstate Commerce Commission outlawed the segregation of Black passengers in buses traveling across state lines.

Eligible for leave, Women’s Army Corps (WAC) private Sarah Keys Evans was excited about going home from Fort Dix to North Carolina to see her family.

On August 1, 1952, Keys Evans boarded a bus in Trenton, New Jersey. Because the bus traveled straight through (she had no changes to make), she knew she had the right to sit where she pleased. She chose a seat in the middle of the bus as the back of any bus tended to be hotter and bumpier than the forward section. In addition, unpleasant smells from the engine frequently drifted in the rear windows.

Near midnight, the bus reached Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina, where a new driver was to take over. As was the custom, the new driver went through the bus and re-checked tickets. When he came to Sarah Keys, he told her to move to the back of the bus. A white marine boarded the bus at Roanoke Rapids, and Keys Evans was told to give him her seat.

Sarah was groggy from sleep but knew her rights. She refused.

The driver proceeded down the aisle, but that was not the end of the issue. As the driver returned to the front of the bus, he announced that all passengers were moving to a different bus with one exception: The woman who refused to change her seat was to stay on the bus as long as she wanted, because she would not be continuing on the route.

Moments later, two policemen came into the terminal. Each one took Sarah by an arm and took her to a patrol car for a ride to the police station. When she asked to call her family, she was told that they would make the phone call for her.

When she arrived home, her parents were frantic, not knowing what happened to her. She realized the police never called. [From America Comes Alive.]

Her case was brought before the Interstate Commerce Commission with Dovey Johnson Roundtree as her lawyer and wasn’t settled until 1955. In Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company, the ICC favored Keys Evans, ruling the Interstate Commerce Act forbids segregation.

We conclude that the assignment of seats on interstate buses, so designated as to imply the inherent inferiority of a traveler solely because of race or color, must be regarded as subjecting the traveler to unjust discrimination, and undue and unreasonable prejudice and disadvantage…We find that the practice of defendant requiring that Negro interstate passengers occupy space or seats in specified portions of its buses, subjects such passengers to unjust discrimination, and undue and unreasonable prejudice and disadvantage, in violation of Section 216 (d) of the Interstate Commerce Act and is therefore unlawful.

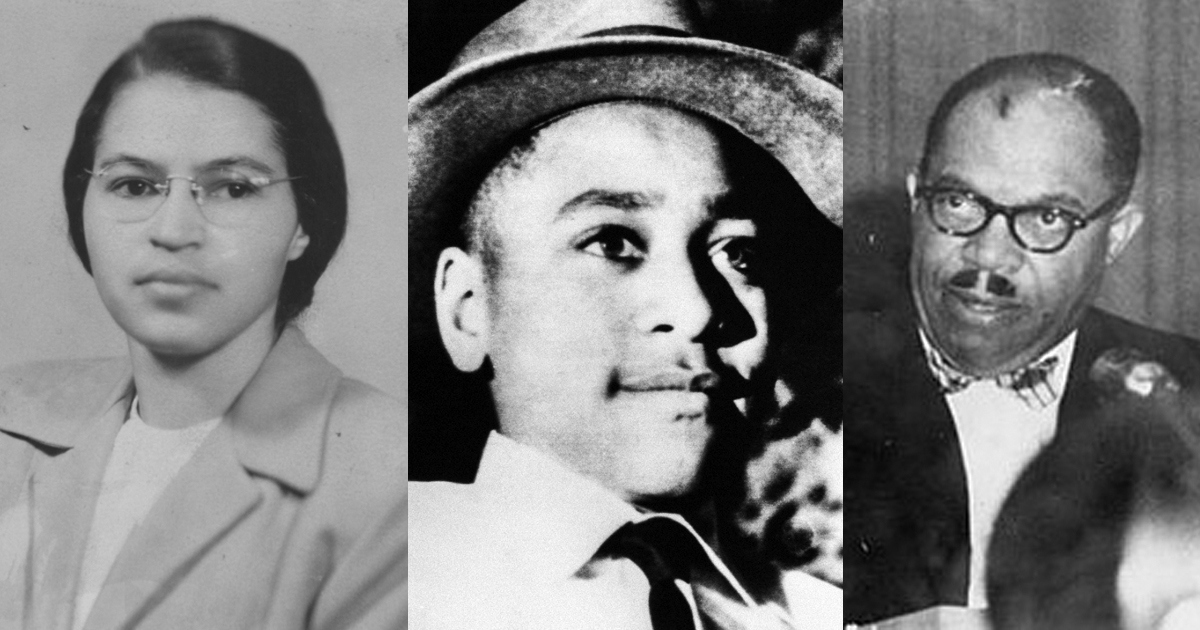

Keys Evans’ action preceded the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Though not the first civil rights movement figure to refuse to give up a seat, Keys Evans helped lay the foundation for protests for years to follow. Her story is seldom told, which is why Take a Seat—Make a Stand is such an important book. Author Amy Nathan self-published Take a Seat because commercial publishers told her they already had a book on Rosa Parks, or that Sarah Keys Evans wasn’t famous so nobody would be interested.

Keys Evans’ action preceded the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Though not the first civil rights movement figure to refuse to give up a seat, Keys Evans helped lay the foundation for protests for years to follow. Her story is seldom told, which is why Take a Seat—Make a Stand is such an important book. Author Amy Nathan self-published Take a Seat because commercial publishers told her they already had a book on Rosa Parks, or that Sarah Keys Evans wasn’t famous so nobody would be interested.

Nathan makes the story accessible for young readers, while not shying away from the brutality faced by African Americans during this time. Nathan explains how a victory in court doesn’t always solve the problem, alluding to negligence of the ruling (especially in southern states, where the ruling was not always enforced) and attacks on African Americans who exercised their new rights. With photos of Sarah Keys Evans and her family throughout the book, Take a Seat—Make a Stand: A Hero in the Family: The Story of Sarah Key Evans, a Civil Rights Hero Who Would Not Be Moved is highly recommended.

Listen to Sarah Keys Evans and Amy Nathan on WNYC below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn