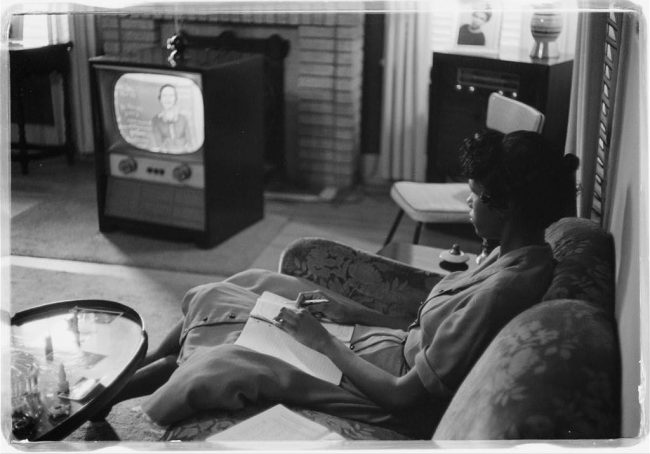

High school student taking a class via television during the period that the Little Rock schools were closed to avoid integration. By Thomas J. O’Halloran. Source: Library of Congress

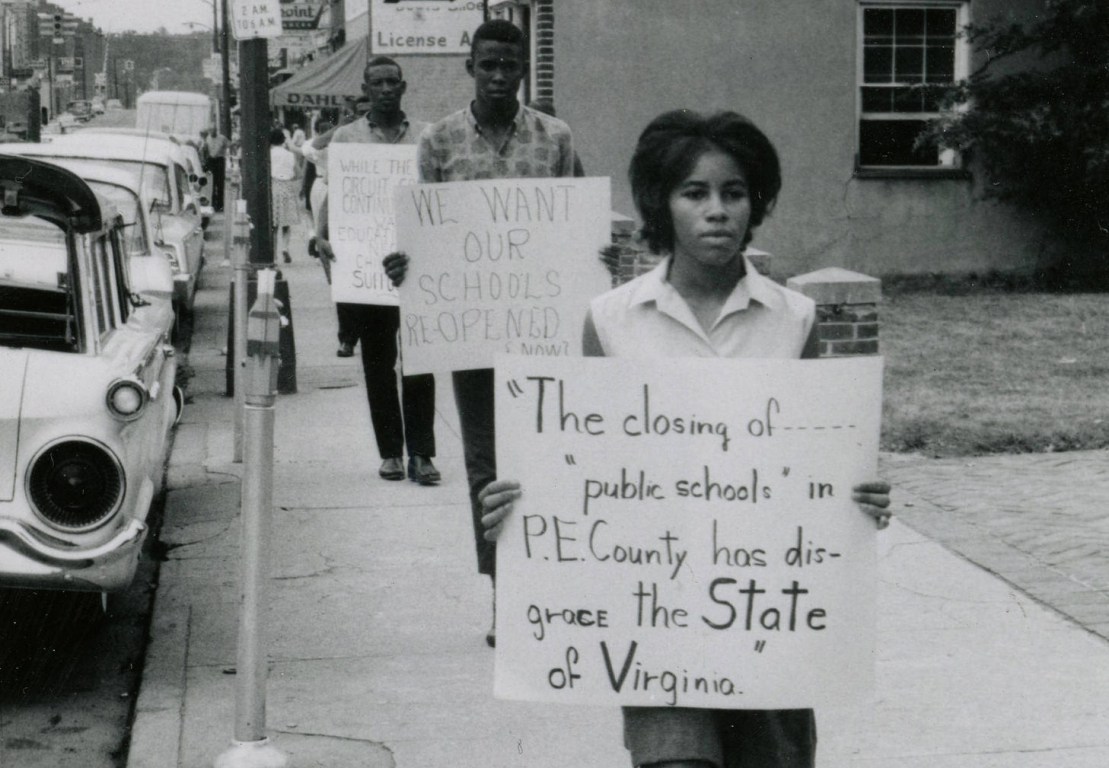

On Sept. 12, 1958, Gov. Orval Faubus closed all Little Rock, Arkansas public high schools for one year rather than allow integration to continue, leaving 3,665 Black and white students without access to public education. During this year, ninety-three percent of white students and fifty percent of the Black students gained access to some form of alternative schooling.

The Encyclopedia of Arkansas explains,

Faubus’s action not only locked students from their classrooms but locked 177 teachers and administrators in the schools, where they had to fulfill their contractual obligations and appear for work, despite the empty classes.

The Lost Year was one of the most peculiar situations in Arkansas history. High school teachers worked in empty classrooms. A private school corporation formed to lease public school buildings and hire public school teachers, but federal courts prevented this. The school district experimented for a few weeks with television teaching by fifteen white teachers on the three commercial television stations. Soon, private schools, aside from the three Catholic parochial schools that already existed, opened to accommodate displaced white students. No private schools for black students emerged.

The Lost Year continued with its peculiarities. . . . The Arkansas General Assembly targeted the NAACP (Act 115) and public school teachers (Act 10) with threatening legislation. The latter required teachers and all public employees to sign affidavits listing all organizations to which they belonged and/or paid dues, while the former immediately fired any teacher or state employee who was a member of the NAACP. . . . Though no academic work was conducted in public high schools in 1958–59, high school football games continued for the season by order of the governor.

. . . Throughout the Lost Year, several groups organized either to support closed schools or to open them. Among those who worked tirelessly for the latter cause was a large group of white, upper-class women called the Women’s Emergency Committee to Open our Schools (WEC). They organized voter registration, promoted the election of moderates to the legislature and the school board, and worked with others after the teacher purge. The Capital Citizens Council (CCC) and the Mothers League of Central High supported segregation. The purge of forty-four teachers on May 5, 1959, brought voters from both sides of the spectrum to organize a recall of either segregationists or moderates from the Little Rock School Board. This twenty-day campaign was led by two hastily formed groups: the Committee to Retain Our Segregated Schools (CROSS) and a group called STOP (which stood for “Stop This Outrageous Purge”), which worked with the WEC. The Lost Year ended with a recall of three segregationist members of the Little Rock School Board on May 25, 1959. Voters in Little Rock, after a year of closed public high schools and after the firing of teachers, were finally willing to accept limited desegregation. Read in full.

Visit the Lost Year website to learn about a film and book based on the history of that year. It is a collaborative project of filmmaker Sandra Hubbard and University of Central Arkansas professor of history Dr. Sondra Gordy. The film can be streamed online.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn