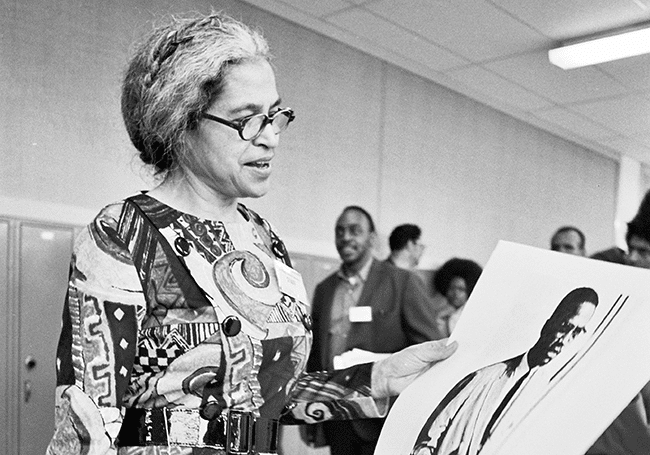

Rosa Parks, Emmett Till, T. R. M. Howard

On Nov. 27, 1955 Rosa Parks attended a packed mass meeting at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church to hear Dr. T. R. M. Howard speak. Howard was the lead organizer in the Emmett Till case, the 14-year-old Chicago boy who had been tortured and murdered near Money, Mississippi.

Four days later, when bus driver James Blake told Parks to give up her seat — “pushed as far as she could be pushed,” she refused.

This story is excerpted from the Rosa Parks biography website by Jeanne Theoharis. Read more:

Rosa Parks was sickened, angry, depressed, horrified. She had been fighting for years to get justice for Black people under the law — Recy Taylor and Gertrude Perkins who’d been raped, Viola White and Claudette Colvin who had been arrested for resisting on the bus. She’d sought protection for Black people and particularly Black men from false charges — like the Scottsboro boys and 16-year-old Jeremiah Reeves. A young Black minister that Raymond [Parks] knew had been killed for appearing to make an advance at a white woman, as had their neighbor Hilliard Brooks for resisting on the bus.

Parks was discouraged. Most of these cases just got swept under the rug.

With Till, people had brought enough attention — an incredible amount of attention — so there had actually been a trial. And yet still, Till’s killers were acquitted. These men who had killed a 14-year-old went free.

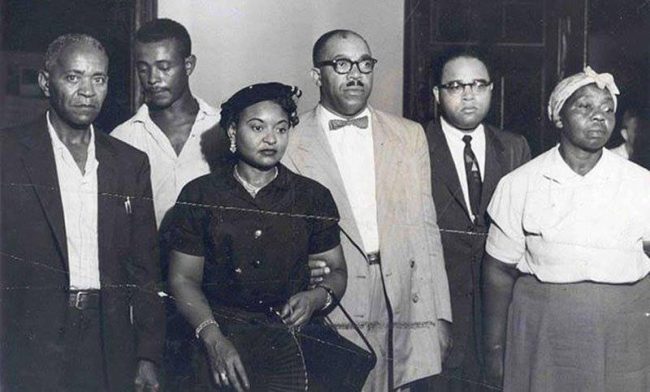

Wiley Nash Carthan, Walter Billingsley, Dr. T. R. M. Howard, Mamie Till-Mobley (Emmett Till’s mother), U.S. Rep. Charles Diggs, and Mandy Bradley. Source: University of Memphis Library

Many years later, she told Emmett Till’s mother that she had thought of him at this moment.

In key ways, then, the Montgomery Bus Boycott was not just a reaction to bus segregation but also to this pattern of injustice in the criminal justice system — and Rosa Parks’ determination to take a stand against it. Parks understood that it was not just about this lynching or this acquittal but about a structure that allowed and protected discrimination, segregation, the differential treatment of Black people under the law. Read more.

Learn more about Parks at the Rosa Parks biography website and in Jeanne Theoharis’s outstanding book The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks.

One of the sources for this post was T. R. M. Howard: Doctor, Entrepreneur, Civil Rights Pioneer by David Beito and Linda Beito, pages 138-139. (Read review here Black Maverick: T. R. M. Howard’s Fight for Civil Rights and Economic Power.)

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn