The Make Reconstruction History Visible project is an opportunity for students and teachers to identify and advocate for public recognition of Reconstruction history in their community and the significant accomplishments made by newly freed people and their white allies.

As part of the Teach Reconstruction campaign, this project helps students learn about this vital era in U.S. history while also playing an active role in giving visibility to an era that has been hidden or misrepresented for too long.

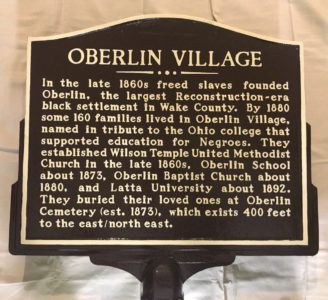

For example, there are nearly 200 historical markers in Charleston County, South Carolina, but the first to commemorate Reconstruction history was not erected until March 2018. After a 25-year campaign for recognition, in January 2017 the National Park Service dedicated the Reconstruction Era National Monument in Beaufort, South Carolina, the first national park dedicated to Reconstruction history.

Note: The Reconstruction Era is often defined as the period of 1865 to 1877, but for the purpose of the map we will accept subjects (people, places, events) with historical significance from Emancipation through the 1880s.

Project Overview

For this project, students (individually or as a class) are invited to identify and document accomplishments in Reconstruction history such as schools, hospitals, election sites, Freedmen’s Bureau offices, Black churches, Black newspapers, Black owned businesses, prominent individuals, organizations, and key events. Students can also choose to document white vigilante violence.

Some resources for exploring local and state Reconstruction history are listed at the end this page. In addition, the Zinn Education Project (ZEP) can connect teachers to our contacts at the National Park Service, the respective state historical society, or our #TeachReconstruction advisors to help identify sites in a particular community.

After students identify a site and write text for a plaque, they can submit the information and images for the Make Reconstruction History Visible online map (see below). Each entry will credit the student or class that contributed the information. Through this process, students will learn how to research and document local history. The stories will be shared via This Day in History, ZEP’s popular social media series, with credit cited to the respective student or class. Read about two classes that piloted this project.

ZEP staff will be available to offer guidance about researching Reconstruction history in the students’ school district. Staff is also available to work with students (individually or as a class) to pursue making the plaque official.

How to Participate

![]() Teachers in elementary, middle, and high school can work with their students to submit draft text, images, and source documentation for Reconstruction history in their community via this online form. The entries can be done as a class, a team of students, or individually.

Teachers in elementary, middle, and high school can work with their students to submit draft text, images, and source documentation for Reconstruction history in their community via this online form. The entries can be done as a class, a team of students, or individually.

This information will be shared publicly on the map below, so it is important that it be accurate, correctly sourced, and the draft text for the plaque should be in students’ own words.

This project is ideal as a culminating activity after engaging in a lesson(s) on Reconstruction era history.

Here are the steps to take:

1. Identify Reconstruction History

Invite students to identify Reconstruction era history (see explanation of time period below) in their community. Students can works individually or in small groups to explore key events and institutions: schools, hospitals, election sites, Freedmen’s Bureau offices, Black churches, Black newspapers, Black owned businesses, prominent individuals, organizations, conventions, teachers’ homes, etc. If help is needed, we recommend contacting your respective state historical society and referring to the resources listed at the end of this page. If additional help is needed, contact the Zinn Education Project for suggestions of books and/or scholars for your state.

2. Research

Have students research the history of the institution, person, or event — keeping a detailed list of all their sources.

3. Select Images

If there is a physical location, have students take a photo of the site. Cell phone photos are fine, using the best resolution possible. If there is not a physical location, they should try to identify historical images that connect to the site.

4. Write Text for Marker/Plaque

If there is not already a marker for the site, or if there is a marker that does not connect the site to the Reconstruction era, have students draft the text following the regulations for the respective state. For example, Alabama allows up to 15 lines with 43 spaces per line. (Read more at the Alabama Historical Association.)

5. Submit

Once you (the teacher) have reviewed and corrected the text, you or the student(s) can upload the text and images on this online form. The form has three sections:

(1) Event or Place

(2) Images

(3) Contact information for the student, teacher, and school. Note that this section of the form invites students to submit their own photo or a class photo. This is optional and depends on the image sharing policies at the school.

6. Review and Publicity

The Zinn Education Project will review the information and respond within two weeks to indicate that the entry is on the Make Reconstruction History Visible Map or with a request for more information.

Once posted, the Zinn Education Project will send a sample press release that the school or school district can use to announce the students’ role in researching and documenting Reconstruction era history.

Optional

Advocating for an official plaque or monument is an optional next step. In many states, this requires both making the case that it is historically significant and raising the funds for a marker. Here, for example, are the steps and fees for South Carolina and Alabama.

Classroom Examples

It was cool shining a light on the unknown history of the journey of African Americans after the Civil War and their successes during Reconstruction. I hope they will put this important history in textbooks. — J. J. Cornelius, 6th grade, Minnesota

Middle school U.S. history teachers Joshua Watne (Minnesota) and D.C. teacher Amy Trenkle (D.C.) piloted the Make Reconstruction History Visible project in the spring of 2018. Read about both examples of engaging students in the mapping project. Trenkle wrote a detailed description of the process she used.

Additional Information

Time Period: Most textbooks cite 1877, when newly inaugurated President Rutherford B. Hayes removed remaining federal troops guarding the South Carolina and Louisiana state-houses, as the end of Reconstruction. However, this implies that federal troops were the main source of protection for Black people in the South and that the main thrust of the Reconstruction era was government support for racial equality. Yet there were never more than 20,000 federal troops in the South during Radical Reconstruction, and after the historic conventions of 1868, that number was nearly halved. While these troops could be a source of protection for freedpeople, with a Southern population of 8 million, the forces allotted to this job were completely inadequate. To fill the gap, Union Leagues and other organizations of Blacks and poor whites organized and armed themselves to combat racial and political violence. Furthermore, the Reconstruction era was characterized by an anti-racist current of Blacks and poor whites struggling to wrest economic and political power from the elites. This current was at times supported, but most often opposed by the federal government. The populist movement of the 1880s and 1890s can be seen as part of this anti-racist wave. For these reasons, we end the Reconstruction era, not with the removal of federal troops in 1877, but with the imposition of Jim Crow laws across the South at the turn of the century. It took decades — with or without federal troops— to turn back the enormous strides African Americans made during the Reconstruction era.

Geography: While our focus is the South, we want students to explore and recognize that Reconstruction affected the whole nation. When enslaved people became free and won the right to vote, something that had previously seemed impossible, was made possible. This unleashed an era of struggle that extended beyond African American rights in the South and included the fight for women’s rights and workers’ rights in the North across the country. Similarly, the anti-racist movement and the subsequent backlash in the South had profound implications for Black rights in the North as well as the struggles of Indians and Chinese laborers in the West.

Suggestion for 15th Amendment: Have students research 15th Amendment celebrations in their city. Historian Stephen West notes that there were celebrations in hundreds of communities around the country after ratification in the spring of 1870. Students might search newspaper databases to which they have access to look for reports about their communities. They can refer to commercial databases (some schools and public libraries subscribe to these often pricey collections); Library of Congress’s Chronicling America is one freely available option; and some states have their own, such as California.

Let the Zinn Education Project team know if you need help identifying Reconstruction era history for your community. We will tap the expertise of our #TeachReconstruction advisors.

Related Projects

In addition to submitting text and images to the Make Reconstruction History Visible map, students can introduce the history to their peers, family, and community in various ways. For example, they could:

- Offer guided tours of Reconstruction history in their community.

- Submit entries to National History Day.

- Create a mini museum in their classroom to introduce fellow students and parents to this crucial history. While not about Reconstruction, a Colorado teacher had her high school students create monuments to hidden history. The projects provide ideas of the varied ways students can represent the history they have learned.

Resources

Below are selected texts, articles, and archival data bases on the Reconstruction era by region or state. The books listed below and many more can be found on these two lists of recommended books and films on the Reconstruction era at the Zinn Education Project (classroom lessons and books for grades 4-12) and Social Justice Books (scholarly texts for background reading). We welcome additional suggestions.

Multiple States

Colored Conventions: Starting in 1830 and continuing through Reconstruction, African Americans came together in state and national political conventions. They strategized about how they might achieve educational, labor, and legal justice. The Colored Conventions archival website includes information and documentation about the conventions in states throughout the United States.

Last Seen: Finding Family after Slavery: An archive of thousands of “Information Wanted” advertisements taken out by people freed from slavery who are searching for family members who had been sold apart. The “Mapping the Ads” page highlights the ads by location in the United States.

National Park Service (NPS) Landmark Theme Study on the Era of Reconstruction by Gregory P. Downs and Kate Masur. This NPS booklet provides an excellent overview of Reconstruction history and concludes with a list of significant sites in Reconstruction history in many states.

Alabama

The Union League Movement in the Deep South by Michael Fitzgerald.

Arkansas

The Encyclopedia of Arkansas offers a wealth of information. There is not a filter for Reconstruction, so for now one place to search is the Time Period: Civil War through Reconstruction (1861 – 1874).

Florida

Georgia

Freedom’s Shore: Tunis Campbell and the Georgia Freedmen by Russell Duncan.

Louisiana

Charles Roudanez and New Orleans Tribune: Archive of the work of Dr. Louis Charles Roudanez, founder of the first Black daily newspaper in the U.S., the New Orleans Tribune, with articles, excerpts, videos, and a timeline.

“The Thibodaux Massacre Left 60 African-Americans Dead and Spelled the End of Unionized Farm Labor in the South for Decades“: A Smithsonian Magazine article by Calvin Schermerhorn that explains how in 1887 African-American cane workers in Louisiana attempted to organize—and many paid with their lives.

St. Bernard Parish Massacre of 1868

Maryland

The Maryland Historical Society offers virtual fieldtrips, including Reacting to Freedom: Diverse Opinions in Reconstruction Era Maryland. Teachers can arrange a “visit” to their classroom via A/V and an internet connection with this program.

Mississippi

“Reconstruction“: By Jason Phillips

Reconstructing Democracy: Grassroots Black Politics in the Deep South after the Civil War by Justin Behrend

The Union League Movement in the Deep South by Michael Fitzgerald

South Carolina

The South Carolina State Historic Preservation Office provides a list of Reconstruction markers. Also see the South Carolina Historical Markers Interactive Map.

Virginia

“‘A powerful story’: How freed slaves helped shape Virginia after the Civil War” by Gregory S. Schneider. This Washington Post article gives great leads for Virginia teachers and students on Reconstruction history.

Washington, D.C.

An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle over Equality in Washington, D.C. by Kate Masur

Western States

West from Appomattox: The Reconstruction of America After the Civil War by Heather Cox Richardson

Note to teachers: We have contacts and resources on Reconstruction from the historical societies in most states. Please contact us so that we can send you current information for your state.

Learn more in the Zinn Education Project national report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction,” and find teaching resources on Reconstruction below.

Teachers and students: Thank you for interest to help

“Make Reconstruction History Visible” in your community.

Contact the Zinn Education Project if you have questions or need assistance.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn