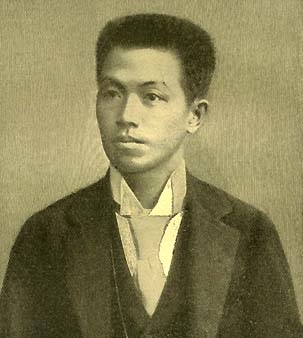

Aguinaldo and army 1900.

The Philippine Republic President Emilio Aguinaldo declared war on the United States on Feb. 4, 1899, when the United States refused to recognize Philippine independence.

In the lesson, History Textbooks: “Theirs” and “Ours”: A Rebellion or a War of Independence?, high school teacher John DeRose has his students analyze textbook passages from different countries and uses resources from the American Social History Project to explore different framing of the same event in history.

Students compare descriptions such as:

“Philippine-American War” vs. the “War of Philippine Independence”

Emilio Aguinaldo as “rebel leader” vs. the “President” who led the Filipinos in the war against the United States

His students watch the video, Savage Acts: Wars, Fairs, and Empire 1898-1904, a 30-minute documentary that links the pageantry of world fairs to the story of the Philippine War and U.S. imperialism. (Savage Acts is available for free online from the American Social History Project.)

Emilio Aguinaldo (ca. 1898)

Savage Acts points out that after Filipinos expelled the Spanish, they established their own independent government. But instead of recognizing Filipino independence, the United States annexed the Philippines and sent troops to crush any resistance. The video examines these events from multiple points of view ranging from antiwar activists like Mark Twain to supporters of imperialism like President William McKinley and describes the camps where U.S. soldiers tortured Filipinos.

After the video, DeRose gives his students eight primary source documents representing an array of perspectives on U.S. annexation. These included speech and article excerpts from McKinley, William Jennings Bryan, Sen. Alfred Beveridge, labor leader Samuel Gompers, the “Colored Citizens of Boston,” Filipino leader Emilio Aguinaldo, a Filipina activist named Clemencia Lopez, and a Filipino newspaper. These resources are in a lesson available online from the American Social History Project/Center for Media and Learning, the organization that created the Savage Acts video. Visit the American Social History Project for all the documents.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn