[Due’s refusal to post bail] gave the Civil Rights Movement a new tactic in the struggle for equality. It was a tactical breakthrough that filled the jails and put pressure on the government. — Paul Ortiz, director, University of Florida Samuel Proctor Oral History Program

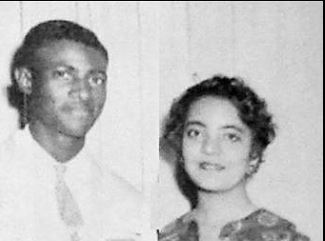

On Feb. 20, 1960 in Tallahassee, Florida, Patricia Stephens Due was fined and arrested at a Woolworth’s lunch counter that denied African Americans the right to be seated.

Due refused to pay a fine and instead, chose to stay in jail.

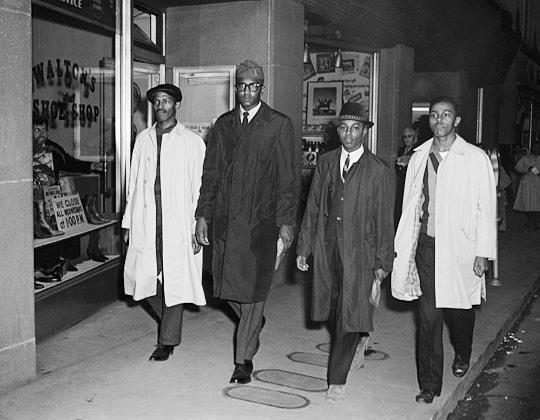

CORE members during a sit-in at Woolworth’s in Tallahassee. Feb. 13, 1960. Patricia Stephens Due is in dark glasses and Charles Steele Jr. is seated closest to camera. The counter was closed until the group left, then reopened. Source: State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory

Here is a description from the Florida Memory Blog:

The February 1, 1960, lunch counter demonstration at the Woolworth store in Greensboro, North Carolina, laid the groundwork for sit-ins across the South. Inspired by the non-violent direct action demonstration of the four students in Greensboro, national CORE asked local chapters to hold sympathy demonstrations in their communities. Ten students, including the Stephens sisters, participated in a sympathy sit-in at Woolworth’s lunch counter in Tallahassee on February 13.

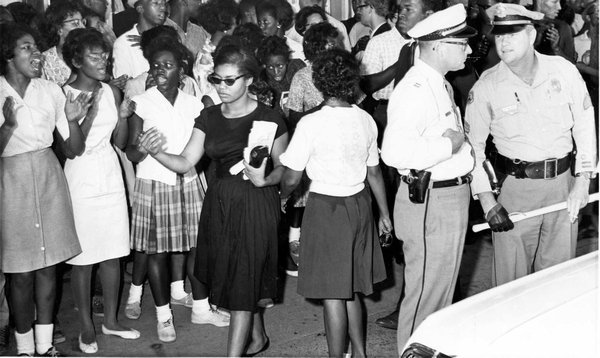

After this first sit-in, Tallahassee CORE planned another for the following Saturday. On February 20, a group of 17 demonstrators made their way to the Woolworth’s lunch counter and ordered food. Most of the group was composed of FAMU students, but there were also high school students participating. A large group surrounded the demonstrators and told them to move from their seats. Seven of them did leave, but the 11 remaining demonstrators were arrested by police. At their trial, they were charged with disturbing the peace.

All of them were found guilty and given the option to pay a $300 fine or spend 60 days in jail. Eight students [Patricia Due and her sister, Priscilla Stephens (Kruize), Henry Marion Steele and Florida A&M University students John and Barbara Broxton, Angelina Nance, Clement Carney, and William Larkins] refused to pay the fine. Rather than pay, they chose to hold the first jail-in of the civil rights movement. As a result, CORE and its principles of non-violent direct action were placed in the national spotlight, and people from all over the country wrote to the jailed students to offer support for their demonstrations. The students were released from jail after serving 49 days. Read in full.

The CRMvet.org website offers some history of the “Jail, No Bail” tactic:

At the October 1960 SNCC strategy conference in Atlanta, some activists argue for “Jail-No-Bail” tactics. They take a Gandhian position that paying bail or fines indicates acceptance of an immoral system and validates their own arrests. And by serving their sentences, they dramatize the injustice, intensify the struggle, and gain additional media coverage.

There is also a practical component to “Jail-No-Bail.” The Movement has little money and most southern Blacks are poor. It is hard to scrape up bail money, and sit-in struggles are faltering — not from lack of volunteers to risk arrest — but from lack of money to bail them out. Moreover, paying fines provides the cops with financial resources that are then used to continue suppressing the freedom struggle. By refusing bail, they render meaningless the no-money-for-bail barrier and by serving time they put financial pressure on local authorities who have to pay the costs of incarcerating them.

As the Freedom Movement continues into the future, the “Jail-No-Bail” tactic is tried again by many of the Freedom Riders. More than 300 of those arrested in Jackson, Miss., refuse to pay their fines and instead served sentences in Mississippi’s notorious Parchman Prison. But in later years, “Jail-No-Bail” is rarely used as a tactic-of-choice. Instead, it is mostly used as a tactic-of-necessity when there is no money available to pay bail or fines. There are a number of reasons for “Jail-No-Bail” becoming the strategy of last resort:

|

Read more reasons why Jail-No-Bail became the tactic of last resort in the full essay on the “Rock Hill Sit-Ins and Jail-No-Bail” at CRMvet.org. Also, read about the strategy at SNCC Digital Gateway.

Find more resources below on SNCC, sit-ins, and on Patricia Stephens Due.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn