By Adam Wasserman

From the summer to the winter of 1835, Black Seminole and Seminole leaders worked to recruit enslaved people in the St. Augustine plantations and build up arms on the southwest Florida coast to resist removal. Covert recruitment melded ties between people enslaved in the fields and the Black Seminoles. Yaha Hajo, a Seminole war chief affiliated with head chief Micanopy’s Black advisor Abraham, and Black Seminole leader John Caesar, second hand to King Phillip, were mostly responsible for the enlistment drive. Caesar, a very influential and intelligent Black Seminole sub-chief, was commissioned by the chiefs to the plantations on the St. John’s region to “hold out inducements to the negroes to join them.” As the Black Seminole leaders secretly moved among the enslaved population, they “endeavored to seduce them from their allegiance to their owners, with promises of liberty and plunder.”¹ A military officer reported the presence of Black Seminoles “tampering with the negroes” on the sugar plantations of Cruger and Depeyster.²

The first Seminole and maroon assault was being planned to coincide with a general uprising of enslaved people in the region. Frank Berry, a former slave from Jacksonville, believed that the Seminoles could be credited for “inciting many uprisings and wholesale escapes among the slaves.”³ General Thomas Jesup would later report not only the close connection between the plantation slaves and Black Seminoles but the “understanding that a considerable force should join on the first blow being struck.”4 General Duncan Clinch foresaw the collusion between plantation slaves and Black Seminoles: “The whole frontier may be laid waste by a combination of the Indians, the Indian negroes, and the negroes on the plantations.” In October 1835, Clinch reported the planter fears of a “secret and improper communication between the refractory Indians, Indian negroes, and plantation negroes.” Again in December, he wrote,

All the information I receive in relation to the movements of the Indians, represent them as being in considerable force, and manifesting a determination to engage in War, murder, and plunder. It appears also that they are joined by the negroes, and if they are not promptly put down, this spirit may extend to the plantations.5

In anticipation of a possible slave uprising, General Hernandez sent a request to Governor Eaton “that a part of the militia should be held in readiness to protect the Inhabitants from any danger”:

Much apprehension is already manifested by the community at large on this subject. And particularly as there are a large number of Negroes amongst the Indians, who may be under the influence of Abolitionists of the North, whose machinations, are now endangering our safety.6

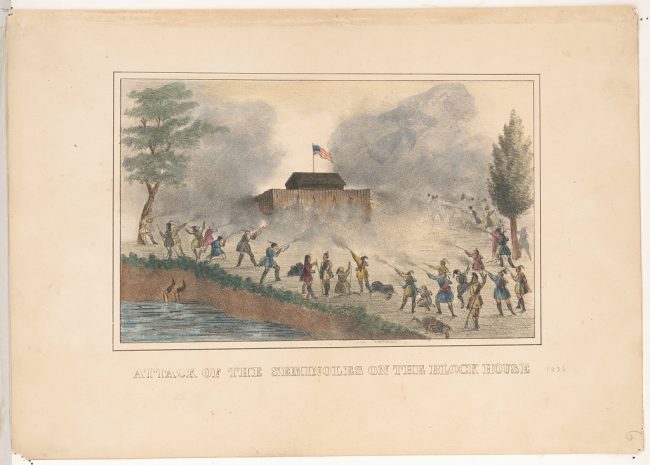

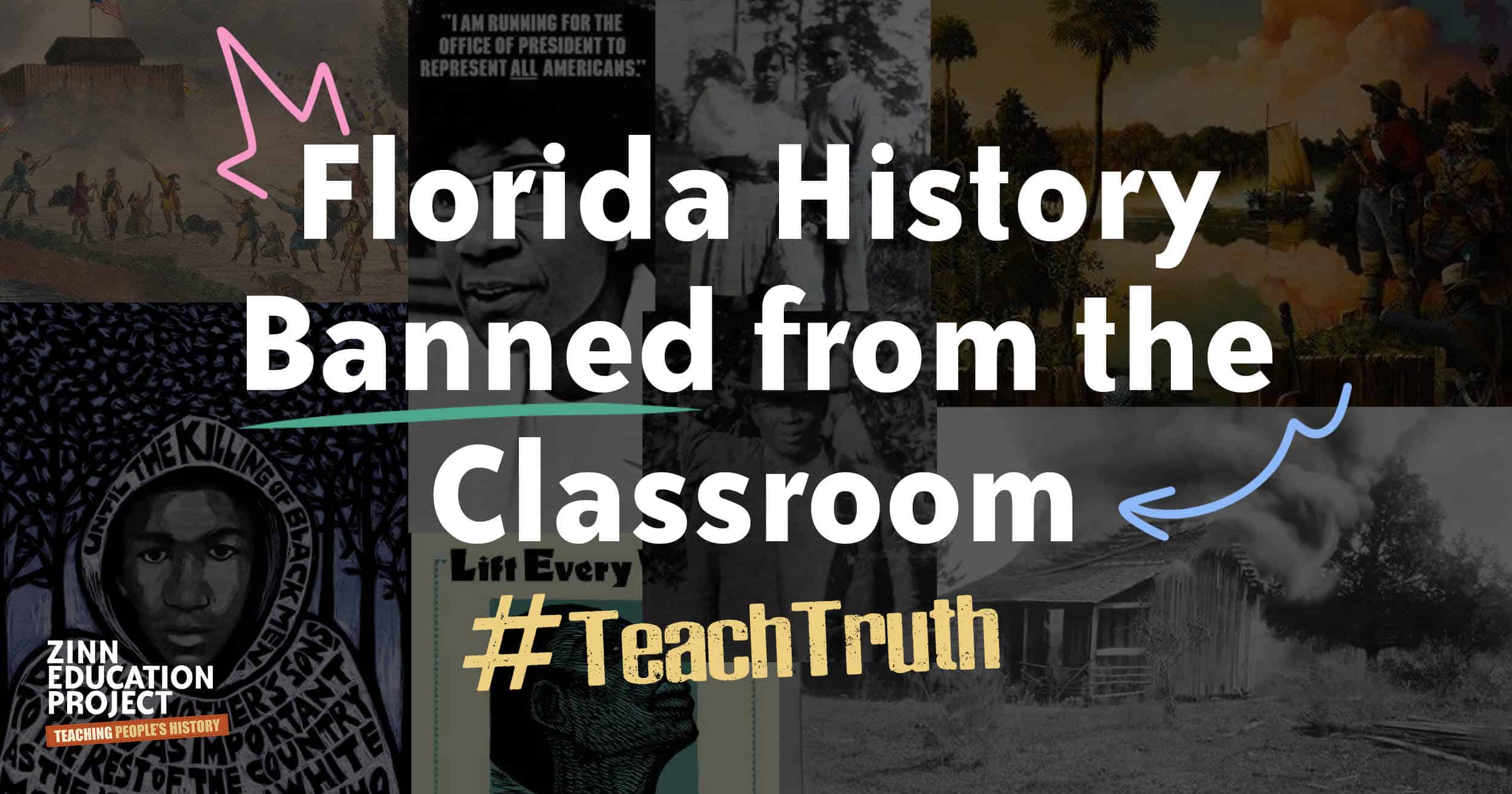

Print shows an attack by the Seminole Indians possibly on a fort on the Withlacoochee River in December 1835. Source: Library of Congress. Click for more information.

Terror swept every corner of the frontier. In Key West, Mayor William Adee Whitehead recalled that the entire town was on edge in the apprehension of a Seminole surprise attack. When a drum sound was heard in the middle of one night, the whites panicked and formed a patrol in fear that “the sound heard might have been some signal agreed upon between the Indians and Negroes, and it was therefore advisable that some of the houses of the latter should be visited.” Whitehead recalled that “the improbability of any cooperation of the Negroes with the enemy was not allowed to have any weight” and the patrols avidly searched the various slave quarters of the city. Whitehead recalled humorously that the “drumbeat” was actually the sound of a dog thumping his leg on a water cistern while scratching off his flees.7 Yet Floridian slaveholders, to their detriment, underestimated the Black Seminoles, free Blacks, and plantation slaves as a serious factor of Seminole resistance. On December 22, 1835, East Florida planter mistress Corinna Brown noted: “There was some alarm that the negroes should rise & fight with the Indians, but this fear has subsided & peace & good order reigns.”8 This was only several days prior to the outbreak of what was arguably the largest slave insurrection in U.S. history.

Slave participants in East Florida hid the Black Seminoles in preparation for the attack. On December 26, 1835, the Seminoles, Black Seminoles, and rebel slaves initiated the most coordinated uprising of Indigenous people and Blacks in the history of the United States. Chief Emathla, or King Phillip, and Black Seminole John Caesar, with an estimated force of 100 to 120 free Blacks and Seminoles, raided and burned down five plantations on the St. John’s River in two days.9 Hundreds of local enslaved people fled to the Seminoles, under arms and covered in war paint to symbolize their new allegiance. East Florida settler Earl C. Tanner recounted:

The general plan of the Indians has been to lurk about the plantations until they can kill the few whites to found and then by force and persuasion carry off the negroes who are immediately painted and armed. In this way near 400 have been already lost in E. Florida and there is not now in all the country east of the River St. Johns a person attending to his usual avocations.10

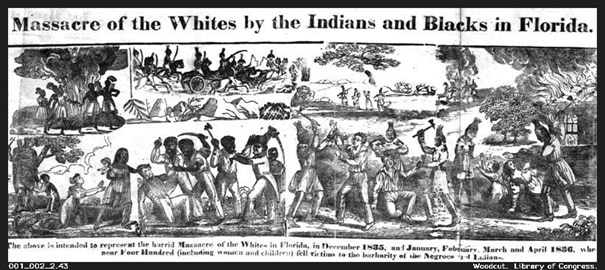

“Massacre of the Whites by the Indians and Blacks in Florida,” engraving depicting the slave uprising at the outbreak of the Second Seminole War, from An Authentic Narrative of the Seminole War. D. F. Blanchard, 1836. Source: Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division LC-USZ62-366.

Plantation after plantation was laid to waste. On the large plantations, slaves absconded in unbelievable numbers. At Spring Garden on the St. John’s River, a plantation owned by an absent overseer from South Carolina, more than three hundred slaves were reported to have been “carried away” by the Seminoles. Woodburne Potter reported the horror: “The scene of destruction of the east side of the river, and along the St. Johns River, is truly heart-rending.” The “principle ravages” occurred on the east side of the St. John’s River, from St. Augustine to the south. Near the Halifax River, the Seminoles destroyed the plantations of Depeyster and ran off with about sixty slaves. His “negroes, with but one or two exceptions,” were “captured and taken off.” They devastated Major Heriot’s plantation and moved off with eighty of his slaves.11 While Joseph M. Hernandez, East Florida militia leader, was escaping from a Seminole raid on his St. Joseph’s plantation, “so closely was he pressed, that the Indians captured about a dozen of the negroes as he was in the act of taking them away.”12 Potter reported a number of enslaved people from East Florida flocking to the Seminole ranks:

But the principle ravages had been along the east side, from St. Augustine to the south, wherever a settlement could be found. Near the Halifax River they destroyed the buildings of Mr. Depeyster, with whose negroes they formed a league, and being supplied by them with a boat, crossed the river, and fired the establishment of Mr. Dummett; but a faithful servant who had concealed himself when he found the Indians approaching, succeeded in extinguishing the flames before they attained much headway. Major Heriot’s plantation was laid waste — his houses were consumed, and eighty of his negroes moved off with the Indians.13

Gad Humphreys, former Indian Agent to the Seminoles, advanced a claim for fifty-nine slaves that fled from his Alachua plantation: “My heaviest loss consisted in negroes; a valuable gang of thirty-four of whom were captured by the enemy in the summer of 1836; some twenty-five others absconded before the war commenced, and took refuge in the Indian country.”14

Almost every plantation from St. Augustine to Cape Florida was consumed by the uprising. By January 6, even the remote Miami River plantation of Richard Fitzpatrick, a territorial council member, found itself under imminent threat from a Seminole invasion. James Wright, the overseer, was forced to evacuate all the slaves and local white families. But Wright faced considerable difficulty removing Fitzpatrick’s sixty slaves, who realized that they themselves were not threatened by the Seminoles and desired to join them. Fitzpatrick wrote that Wright “was obliged to abandon the plantation, leaving everything behind him except the negroes, which by great exertions he removed, and thus prevented them from falling into the hands of the Indians . . .”15

In the month of January alone, the uprising eradicated sixteen large sugar plantations — some of the wealthiest in the entire United States.16 The East Florida planters evacuated or bunkered down in absolute terror at their imminent destruction. A St. Augustine refugee explained why the white residents had good reason to fear:

Now just conceive their position-eight hundred or one thousand warriors, animated by sentiments of hatred and revenge, and well aware what is to be there fate by losing their superiority-with them three or four hundred negroes of their own, better disciplined and more intelligent than themselves, to whom there is a daily succession of runaway negroes from the plantations, supplied with arms and ammunition from the deceased whites. Conceive these people living upon roots, if necessary, for weeks entire, flying before regular charges of disciplined troops, or avoiding fortresses or stockades; but from ambushes and retreats cutting off the most valuable lives of individuals, or attacking and destroying valuable properties.17

A letter from St. Augustine lamented that the present crop was burnt and destroyed and there were no hopes of planting for the approaching season or even the following one: “in the meantime starvation must be the consequence with hundreds who, heretofore, were in comparatively easy circumstances.”18 Hundreds of wealthy families who had lived easy off of the exploitation of slave labor were thrown into starvation and absolute poverty at the hands of their own “property.” One sugar plantation fell after another as the Seminoles, maroons, and plantation slaves combined in a frenzied scourge of revenge and retaliation. An account summarized the horrors East Florida planters experienced — the culmination of abuses and oppression they had heaped on the Seminoles and blacks for many years — “a great number of the most valuable plantations have been totally destroyed, and whole families missing; and as the Indians have been frequently discovered dancing to and fro around their burning dwellings, there can be but little doubt but some of the missing were consumed in them.”19 Wealthy planters, “who from a competence acquired by industry and persevering enterprise,” cried a report from St. Augustine, “have, in many instances, been suddenly overwhelmed with absolute poverty and the deepest distress.”20 The refugees of St. Augustine had formed a committee pleading with the Federal government to supply them relief and emergency rations to save them from starvation. What had once been a bustling region with a highly lucrative slave-based sugar economy now found itself crushed under the retaliation of the very people who had been excluded and exploited to build its wealth. Myer M. Cohen, an officer during the first months of the war, wrote in his account:

The plantations extending from Cape Florida to Augustine, were visited in turn, and nearly all the buildings, including the sugar mills, were destroyed. It is estimated that property to the amount of two hundred thousand dollars was burnt in one week. Nothing was left except the storehouses containing corn and provisions; these were reserved by the Indians for their own consumption. Independently of this destruction of property, the loss to some of the planters was ruinous, in respect to their negroes; upwards of three hundred having been carried off; Col. Rees alone lost about one hundred and sixty.21

Seminole Chief Osceola (1804–1838) by George Catlin. Source: Smithsonian American Art Museum, public domain.

In the month of January alone, five hundred families were driven from their homes “in a situation bordering upon starvation,” and sought refuge in St. Augustine “and other fortified places.”22 As the world was falling apart around them, the planters were aware of who they had to fear. They assembled three hundred of their slaves within St. Augustine to prevent them from joining arms with the Seminoles and Blacks: “It was feared . . . that their sympathies would be with the Indians, and that they would aid in concert with them.” Most of these slaves had “lived on the frontiers in the neighbourhood of the Indians, spoke their language, and many of the men had wives among the Indian negroes, and the Indian negroes had wives among them.” As the slaves crowded within St. Augustine, the planters felt “strong apprehensions . . . that they would fire the town, and that, during the confusion resulting therefrom, the Indians might rush in.”23

Slaves were evacuated from the St. Joseph’s plantations of Bulow, Williams, Dupont, and Hernandez. They would have undoubtedly disaffected with their counterparts had they not been constrained in the city. White refugees within the city formed a militia patrol. But when they attempted to stock up on arms and ammunition, they found that only thirty or forty rusty muskets, rifles, and shotguns were left in the city, not ten of which could fire. Furthermore, all the powder had been bought up by a party of Seminoles before hostilities broke out. Later they learned that free Blacks and urban slaves in St. Augustine had secretly assisted the uprising by providing the Seminoles and plantation slaves with all the good arms and ammunition from the city’s stores. In apprehension, the planters took their slaves to Anastasia Island. Shortly after, the Seminoles destroyed the St. Joseph’s area.24 The conflict was appearing to be, as Thomas Benton put it, a war of the “colored races upon the white!”

While reports and letters decried the “savagery” and “barbarity” of the Seminoles and Blacks in their massacres of the East Florida whites, one account conceded that an escaped slave, “who had enlisted in the cause of the enemy,” felt pity for and protected the wife of William Godfrey and their several children from the Seminoles, who sought her out because her husband had enlisted in the East Florida militia. The escaped slave had left his own children in bondage and worried that the whites would possibly harm them if he was found a culprit for murdering a family. He provided the starving Mrs. Godfrey and her children with food, water, and blankets, even helping them escape from their miserable, diseased hide-out in the swamp “although at the risk of his own life!”25

The slave rebels of East Florida now entered the broader theater of combat. English traveler John Benwell, finding himself entrenched in Seminole war fighting while traveling through Florida, encountered a fugitive slave in the vicinity of East Florida: “He refused to tell me his master’s name, but said there were hundreds of negroes fighting with the Indians, six from the same plantation as himself.”26 A week into 1836, Capt. F.S. Belton wrote from Fort Brooke: “This place is invested by all the Florida Indians in the field, with a large accession of Negroes, particularly from the plantations of Tomoka & Smyrna.”27 In late January, Lieutenant Joseph Harris noted of the Seminoles: “They have been strongly reinforced of late by runaway and stolen negroes.”28 In June, Benjamin A. Putnam wrote a letter to the Secretary of War Lewis Cass: “Many have escaped to and joined the Indians, and furnished them with much important information and if strong measures were not taken to restrain our slaves, there is but little doubt that we should soon be assailed with a servile as well as Indian War.”29 While conceding to the slave threat, Putnam was unable, or perhaps willing, to admit what the war had already become.

General Thomas Sidney Jesup, on the other hand, testified to the war’s true character. In December 1836, Jesup warned that the possible results of the slave revolt could be drastic if it spread, going so far as to declare the conflict “a negro war”: “This you may be assured, is a negro, not an Indian war; and if it be not speedily put down, the south will feel the effects of it on their slave population before the end of the next season.” Jesup, being a newcomer to the war, did not realize that the St. John’s River valley had been feeling its effects for over a year by this time. Intelligence reports soon made him aware that the “depredations committed on the plantations east of the St. John’s were perpetuated by the plantation negroes, headed by an Indian negro named John Caesar.”30

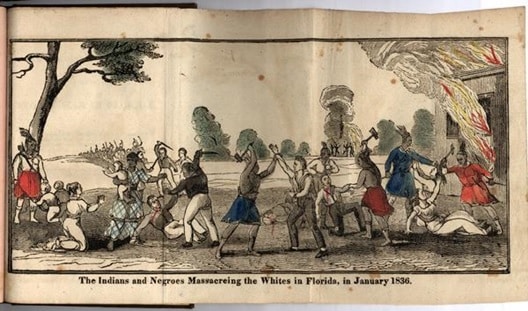

“The Indians and Negroes Massacring the Whites in Florida, in January 1836,” woodcut engraving depicting the slave uprising at the outbreak of the Second Seminole War, from A True and Authentic Account of the Indian War in Florida, Saunders & Van Welt, 1836.

A total of 21 sugar plantations in East Florida were obliterated in the first few months of the uprising, destroying the region’s extensive sugar industry. Woodbine Potter estimated the great costs that the insurrection inflicted on the East Florida plantation economy: “The loss of these planters is incalculable — it cannot fall short of two millions of dollars in improvements alone, independent of the immense inconvenience which they must suffer in not being able to make their crops.”31 In April 1836, East Florida marshal Samuel Blair suggested that “the present condition of the Country is such as to require unusual vigilance in relation to its slave population” and that it was generally believed the fugitive slaves from St. Augustine “held communication with the Indians” at the war’s outbreak. Likewise, East Floridian Jane Murray Sheldon reported that it eventually became general knowledge that the slaves had conspired with the Seminoles in the outbreak of hostilities:

We remained in St. Augustine two years, during which time I saw many Indian prisoners, who were brought in to be sent West. There were a good many negroes captured with them, and it came to light that the negroes were in sympathy and had aided them in the first outbreak. I saw a number of the Cruger and Depyste slaves and from them learned that they had secreted the Indians near there until the main body came up.32

General Jesup later became aware of this secret arrangement between the Seminoles, Black Seminoles, and slaves to join together in arms at the outbreak of war:

Having been apprised, by prisoners taken in the preceding campaign, of an arrangement entered into previous to the war, through the Seminole negroes, between the Indians and their slaves, that so soon as hostilities should commence, the latter were to join them and take up arms, I informed the Indians that all their negroes must be separated from them, and sent out of the country.33

Most traditional and even many revisionist Seminole war historians have failed to recognize or distinguish the hundreds of plantation slaves who rose up in arms at the outbreak of the Second Seminole War. Some historians have done so, such as Kenneth Wiggins Porter’s excellent work on the involvement of slaves in the Seminole War, but still failed to place their actions in the context of a large-scale slave revolt. Even the revisionist history on slavery that has emphasized slave resistance and revolts, discussing the Black Seminoles in-depth, has failed to mention the St. John’s River uprising as a distinct slave rebellion. It becomes even more amazing that this slave revolt has been discarded from the pages of history when considering its scale of white death, property-loss, slave participation, duration, and intensity. The estimated number slave participants ranges from four to five hundred to over a thousand. Florida historian Canter Brown claims that “When open warfare commenced in December 1835 and January 1836, hundreds-if not 1,000 or more-bondsmen cooperated by deserting to Indian and black settlements.”34 It’s little wonder then why Secretary of War Lewis Cass instructed Major General Scott, upon assuming command of the war, that he was “to allow no pacification with the Indians while a living slave belonging to the white man remained in their possession.”35 This order blatantly proved that the primary objective of the war was to hunt down fugitive slaves.

There are multiple reasons why an insurrection with the magnitude of the East Florida slave revolt has been marginalized, ignored, or simply forgotten by mainstream history: For one, the orthodox historical belief that there were no large-scale slave revolts or uprisings after the Nat Turner revolt of 1831; the Southern press was effectively censored following the Nat Turner revolt, fearing that news of slave unrest could incite another revolt; many Seminole War historians have failed to distinguish the plantation slaves, newly emancipated at the outbreak of the war, from the Black Seminole maroons who had long been Seminole allies; the 1836 “gag rule” that prohibited Congressional discussion of abolitionism or any topic involving slavery; the press reports at the time that claimed the Seminoles “captured” or “stole” plantation slaves during their raids, making it appear to outsiders as if the rebel slaves were taken against their will. But letters, reports, diaries, and other sources of information from Floridians, military officials, and Seminole War participants make it clear that many were aware that their slaves had allied with the Seminoles, plotted the uprising, and left the plantations on their own free will. In addition, planters, mostly incapable of believing that their slaves could possibly harbor any animosities towards their state of bondage, often used the terms “stolen” or “captured” interchangeably with running away. They wanted to make it appear, in the words of a Seminole War officer, as if their slaves were “attached to their owners from motives of gratitude and affection.”36

To contemporary observers, the Second Seminole War appeared to be an all-out race war between whites and people of color. U.S. politicians who debated the Seminole war at the time surely believed the conflict was drawn along racial lines. Expansionist politician Thomas H. Benton spoke to the Senate of the desolation of 41,000 square miles in Florida “made so by the ravages of colored races upon the white!”37 Blacks in Florida at the time usually belonged to one of three categories: 1) Plantation slaves concentrated on the cotton and sugar plantations of Middle and East Florida 2) Free Blacks in the vicinity of St. Augustine and Pensacola who had attained their freedom under Spanish rule 3) The Black allies to the Seminoles who were either born among the Seminoles, of mixed Seminole-Black blood, lived their lives in Seminole territory, or were more recent fugitives. All three of these groups would come to play a pivotal role in the initial outbreak of the Second Seminole War.

The revolt handicapped the powerful sugar economy of East Florida, inflicting more destruction, loss of civilian life, and loss of property than any other event in the long, expensive, and bloody war. A number ranging from four hundred to a thousand slaves, a larger number than any other recorded slave insurrection, joined the Seminoles and their Black allies in eradicating the Florida frontier, secretly corresponding with their emissaries, hiding them about the place, and taking up arms from their dead masters when the uprising began. While apparently a failure, some slaves still remained among the Black Seminoles when they received their freedom years later, meaning that a handful of slaves had openly revolted against their bondage and actually won — something that was unheard of again until the Civil War.

The slave revolt would continue to play a central role throughout the first two years of the Seminole war, contributing to its successes and failures, climaxes and downturns. Many of the unique features of the Seminole war, for instance, its prolonged length, could be attributed to the momentum furnished by the defected slave population of the St. John’s River region.

This post is a revised excerpt from A People’s History of Florida 1513-1876: How Africans, Seminoles, Women, and Lower Class Whites Shaped the Sunshine State by Adam Wasserman. Read the free PDF.

Footnotes

- Douglas, Thomas. Autobiography of Thomas Douglas: Late Judge of the Supreme Court of Florida. New York: Calkins & Stiles, 1856. 121.

- Cohen, Notices of Florida and the Campaigns, 81, 87.

- Florida Slave Narratives, 28.

- Cited in Franklin, John H. Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation. New York: Oxford UP, 1999. 87-88.

- A&NC 4: 386-387; Carter, Territorial Papers, XXV, 210.

- Carter, Territorial Papers, XXV, 190.

- Peter, Thelma ed. “William Adee Whitehead’s Reminisces of Key West.” Tequesta XXV (1965): 17.

- Corinna Brown to Mannevillette Brown, Dec. 22, 1835, Mandarin, FL in Denham, James M. and Keith L. Huneycutt. Echoes from a Distant Frontier: The Brown Sisters’ Correspondence from Antebellum Florida. Charleston, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2004. 16.

- ASPMA 7: 820.

- Tanner, Earl C. “The Early Career of Edwin T. Jenckes A Florida Pioneer of the 1830’s.” Florida Historical Quarterly 30 (January 1952): 275.

- Potter, War in Florida, 117-118; ASPMA 6: 20-21.

- U.S. Congress House. “Joseph M. Hernandez. (To accompany Bill H.R. No. 877.) July 6, 1838.” 25.2 Report 1043: 2.

- Potter, War in Florida, 118.

- U.S. Congress House 25.3 Ex. Doc. 225: 106.

- Cited in Black, Hugo L. “Richard Fitzpatrick’s South Florida Plantation, 1822-1840, Part II: Fitzpatrick’s Miami River Plantation.” Tequesta XLI (1981): 40.

- Sprague, Florida War, 106.

- ASPMA 6: 20.

- ASPMA 6: 21.

- A True and Authentic Account of the Indian War in Florida, Giving the Particulars Respecting the Murder of Widow Robbins, and the Providential Escape of Her Daughter Aurelia, and Her Lover, Mr. Charles Somers, After Suffering Almost Innumerable Hardships. The Whole Compiled From the Most Authentic Sources . . . New York: Saunders & Van Welt, 1836. 17.

- ASPMA 6: 20.

- Cohen, Notices of Florida and the Campaigns, 80-81.

- A True and Authentic Account of the Indian War in Florida, 5.

- Douglas, Autobiography, 120-122.

- Porter, “Florida Slaves and Free Negroes in the Seminole War,” 391, 401-403.

- A True and Authentic Account of the Indian War in Florida, 13-16.

- Benwell, John. An Englishman’s Travels in America. Kessinger Publishing, 2004. 97.

- Cited in Porter, “Florida Slaves and Free Negroes in the Seminole War,” 395.

- ASPMA 6: 565.

- Cited in Porter, “Florida Slaves and Free Negroes in the Seminole War,” 398.

- ASPMA 7: 820-821, 876.

- Boyd, Mark F. “The Seminole War: Its Background and Onset,” 59-69; Potter, War in Florida, 119.

- Carter, Territorial Papers, XXV, 328-329; Sheldon, Jane M. “Attacks Near New Smyrna, 1835-1856.” Florida Historical Quarterly 8 (April 1930): 192-93.

- Sprague, Florida War, 194.

- ASPMA 7: 21; Cohen, Myer M. Notices of Florida and the Campaigns. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida P, 1964. 81.

- ASPMA 6: 58.

- Brown Jr., Canter. “Race Relations in Territorial Florida 1821-1845.” Florida Historical Quarterly 73 (1995): 304.

- Porter, Kenneth W. “Florida Slaves and Free Negroes in the Seminole War, 1835-1842.” Journal of Negro History 28: 392-395; Horseman, Reginald. Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism. Cambridge, MA: Howard University Press, 1981. 205.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn