On Jan. 9, 1966, Vernon Dahmer announced on the radio that he would pay the poll tax for anyone who could not afford to register to vote. (Despite the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, a poll tax was still charged in local elections in Mississippi.)

On Jan. 9, 1966, Vernon Dahmer announced on the radio that he would pay the poll tax for anyone who could not afford to register to vote. (Despite the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, a poll tax was still charged in local elections in Mississippi.)

The next day, Dahmer’s home was firebombed by the Ku Klux Klan. Dahmer guarded the front door while his wife and children escaped out the back. He died the next day from severe burns and smoke inhalation.

Here is a brief description of his extraordinary life of activism, excerpted and adapted from the excellent profile of Vernon Dahmer on CRMvet.org.

Vernon Dahmer: Brief Background

Vernon and his wife Ellie Dahmer had a 200-acre farm, a small store, and an independent saw mill in north of Hattiesburg, Mississippi. They were one of the few prosperous Black families in southeast Mississippi, providing jobs and assistance for others in the community.

Dahmer was a leader and prime mover of the Forrest County NAACP. “If you don’t vote, you don’t count,” he told his friends and neighbors. Inspired by his example, a chapter of NAACP Youth Council became active. Among the young council members were high school students Joyce and Dorie Ladner, who traveled with Dahmer to statewide NAACP meetings in Jackson.

With Dahmer’s support, military veteran Clyde Kennard applied for admission to Mississippi Southern College, only to be framed on petty charges and sent to Parchman Prison to silence him. Dahmer, Medgar Evers, and the Ladners struggled for years to free him from prison.

In 1961, Dahmer invited the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to set up a voter registration project in Forrest County. They faced fierce opposition from Circuit Clerk and Registrar of Voters for Forrest County Theron Lynd and the Klan.

In early 1964, Dahmer was one of the speakers at Hattiesburg Freedom Day, a mobilization of would-be Black voters attempting to register en mass at the county courthouse. More than 150 courageous Black citizens defiantly lined up to register. Only a handful were allowed in the building, and few — if any — were added to the voting rolls. Some of those attempting to register were fired from their jobs, others were threatened with violence.

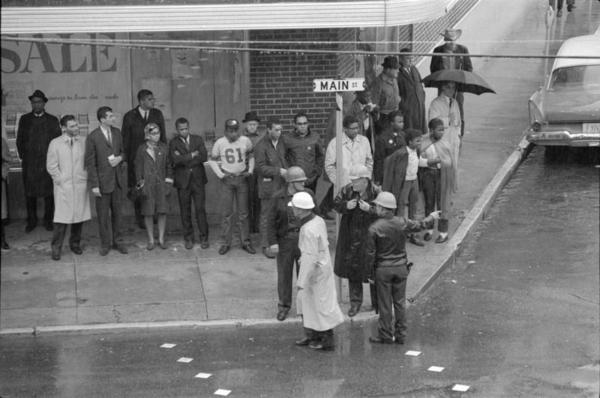

Demonstrators in the rain on Hattiesburg Freedom Day in 1964. Click image to learn more. Credit: Moncrief Collection, MDAH

Following passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Dahmer obtained the right and the materials needed to register voters and collect poll taxes at his store. This would have facilitated a great increase in voter registration by African Americans in Forrest County. It was on the day after he announced this opportunity that his house was bombed.

Harold Dahmer looks over the smoking ruins of his family’s home and car the morning after they were firebombed on January 10, 1966. Credit: Moncrief Collection, MDAH

Four of Dahmer’s sons were serving in the U.S. military to “defend democracy,” only to have their father murdered in his fight for the democratic right to vote in the United States. They returned home for his funeral and were joined by hundreds of mourners at Dahmer’s funeral on Jan. 16, 1966.

Four of Vernon Dahmer’s sons observe the family home burned to the ground. Photo by Chris McNair, courtesy of Jerry Mitchell

Demonstrators sing on the courthouse steps on the morning of Vernon Dahmer’s funeral, Jan. 16, 1966. Credit: Moncrief Collection, MDAH

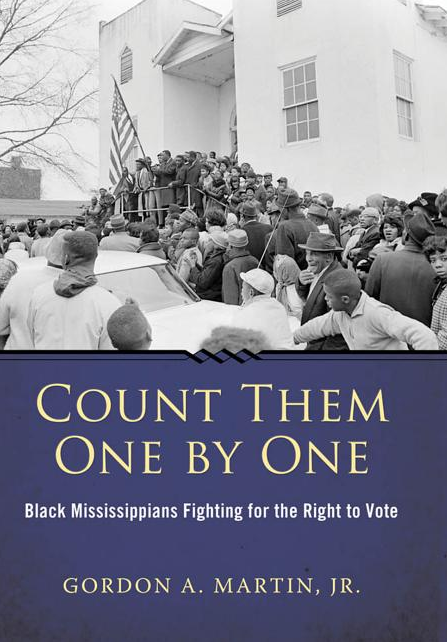

Two key resources on Dahmer are the profiles on the SNCC Digital Gateway and CRMvet.org websites. We also recommend Count Them One by One: Black Mississippians Fighting for the Right to Vote by Gordon A. Martin Jr. and Race Against Time: A Reporter Reopens the Unsolved Murder Cases of the Civil Rights Era by Jerry Mitchell, whose investigative journalism played a key role in the convictions of Klan imperial wizard Sam Bowers for ordering the fatal firebombing. For images, visit the Moncrief photo collection.

On Monday, January 6, 2020, a statue of Vernon Dahmer was unveiled outside the Forrest County Courthouse in Mississippi.

Find resources below for teaching about the fight for voting rights and terrorism in U.S. history.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn