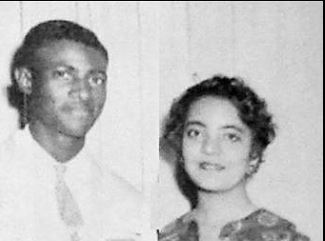

On Feb. 6, 1961, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) sent four volunteers to Rock Hill, South Carolina to sit-in: Charles Sherrod, Charles Jones, Diane Nash, and Ruby Doris Smith-Robinson.

They were sentenced to 30 days. This followed a sit-in a week earlier when 10 African American students in Rock Hill (to become known as the Friendship Nine) were arrested for requesting service at a segregated lunch counter.

Saying “Jail, No Bail,” both groups (except for one person) refused to post bail and demanded jail time rather than paying fines as a statement “that paying bail or fines indicates acceptance of an immoral system and validates their own arrests” and as a practical strategy when financial resources were limited.

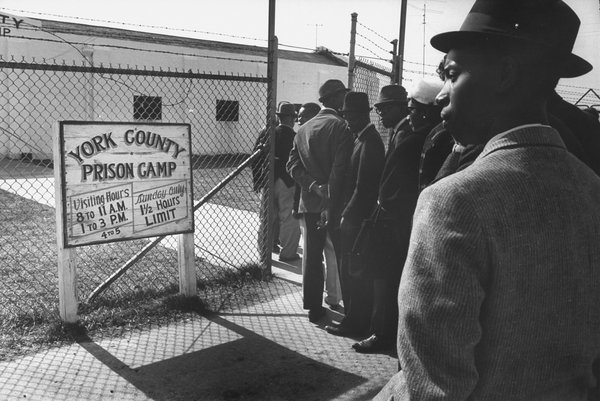

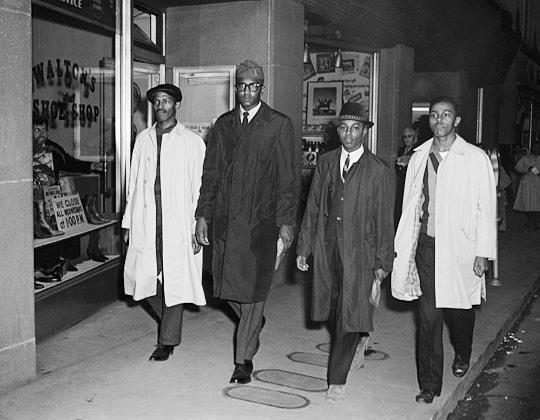

Supporters visit the sit-in activists in Feb. 1961. Source: © Lynn Pelham, LIFE Picture Collection, Getty Images

The Civil Rights Movement Archive describes the origins and use of the “Jail-No-Bail” tactic:

At the October 1960 SNCC strategy conference in Atlanta, some activists argue for “Jail-No-Bail” tactics. They take a Gandhian position that paying bail or fines indicates acceptance of an immoral system and validates their own arrests. And by serving their sentences, they dramatize the injustice, intensify the struggle, and gain additional media coverage.

There is also a practical component to “Jail-No-Bail.” The Movement has little money and most southern Blacks are poor. It is hard to scrape up bail money, and sit-in struggles are faltering — not from lack of volunteers to risk arrest — but from lack of money to bail them out. Moreover, paying fines provides the cops with financial resources that are then used to continue suppressing the freedom struggle. By refusing bail, they render meaningless the no-money-for-bail barrier and by serving time they put financial pressure on local authorities who have to pay the costs of incarcerating them.

As the Freedom Movement continues into the future, the “Jail-No-Bail” tactic is tried again by many of the Freedom Riders. More than 300 of those arrested in Jackson, Miss., refuse to pay their fines and instead served sentences in Mississippi’s notorious Parchman Prison. But in later years, “Jail-No-Bail” is rarely used as a tactic-of-choice. Instead, it is mostly used as a tactic-of-necessity when there is no money available to pay bail or fines. There are a number of reasons for “Jail-No-Bail” becoming the strategy of last resort:

-

- In the Deep South, racism and segregation do not yield to moral witness or appeals for decency and justice. As the Movement progresses, it becomes increasingly clear that only a political movement and political power can force an end to racial and economic injustice. As a result, in the years to come, student activists evolve into community organizers, and tactics shift from students courageously dramatizing the iniquities and abuses of segregation to building popular mass movements for justice. Drama and media coverage become less important than broad participation and stubborn, long-haul determination.

- When the Movement expands out of college centers into the impoverished and oppressed rural counties of the Deep South, it encounters sheriffs and jails far more vicious and dangerous than those faced by the student sit-ins. Freedom fighters in rural jails face beatings, rapes, and ultimately murder. It is simply too risky to leave anyone in jail if there is any way to get them out.

In 2015, Judge John C. Hayes III overturned the convictions of the Friendship Nine, stating: “We cannot rewrite history, but we can right history.”

Learn More

“Rock Hill Sit-Ins and Jail-No-Bail” at the Civil Rights Movement Archive includes more reasons why Jail-No-Bail became the tactic of last resort.

SNCC Digital Gateway on Rock Hill “Jail No Bail”

Thomas Walter Gaither oral history interview conducted by Joseph Mosnier in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania for the Library of Congress. Gaither discusses the student sit-ins in Orangeburg, South Carolina, joining the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and being arrested for protesting in Hollywood, Florida.

Find teaching resources below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn