More than 5 million people have been killed in Democratic Republic of the Congo since the late 1990s, home to some of the most serious human rights violations since World War II. A look back at Congo’s history sets the stage. From 1885 to 1908, Congo was colonized by the king of Belgium, Leopold II, who took it as his own personal property. Initially, Leopold did not know that Congo was rich in wild rubber, one of the hottest commodities on the global market at the time. At the opening of the 20th century, Congo was the most profitable colony in Africa. It is estimated that Leopold made about 220 million francs, equivalent to $1.1 billion today.

Artwork by Eduardo Relero, drawn in front of the Apple store in Madrid in June of 2016 for an Amnesty International campaign against child labor. See more street art by Relero. Used by permission of the artist.

Leopold refused to pay a fair price for labor or resources, and instead enslaved the population through a terror campaign, forcing the Congolese to harvest rubber. The magnitude of the violence is incomprehensible. During Leopold’s rule, 8 million to 10 million people were killed through a variety of colonial policies, making it one of the worst cases of European colonial brutality.

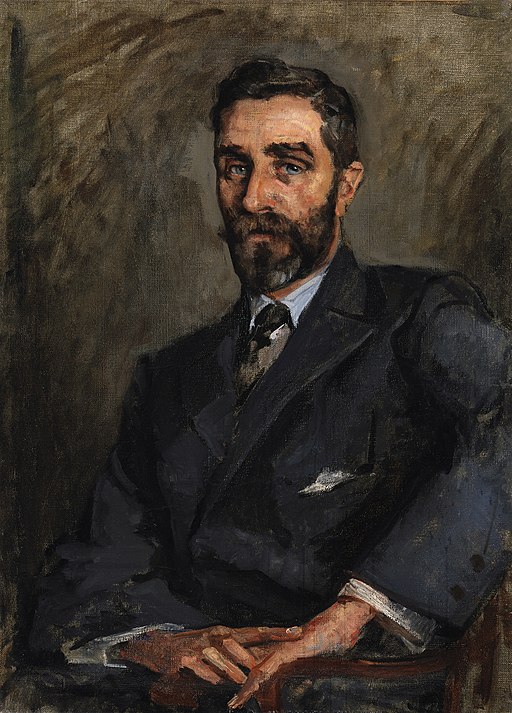

Congo’s colonial history foreshadows the current instability and violence plaguing the country. Since 1997, more than 5 million people have been killed there, making it one of the bloodiest battle zones since World War II. That year marked the end of a 32-year dictatorship (1965–1997) led by Joseph Mobutu, also known as Mobutu Sese Seko, a generously compensated and welcomed friend of six U.S. presidents. He came to power by assisting the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in assassinating the first democratically elected prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, in 1961. They wanted Lumumba dead because of his desire to nationalize natural resources in Congo where the money could be used to create a functioning state.

Patrice Lumumba (center), at the 1960 round table conference in Brussels to discuss Congo’s independence. Source: National Archives of The Netherlands.

Just as the bloodshed of the colonial period was financed by highly lucrative natural resources like rubber, the violence today is likewise fueled by natural resources. One of those is coltan, a mineral required for cell phone production. Congo is rich in coltan. By studying this history, we can see a direct connection between the brutality of colonialism and the contemporary injustice in Congo: highly coveted natural resources, exploited by distant, powerful nations.

The mixer activity includes roles for:

- Nzinga Mbemba Afonso / Afonso I, king of the Kingdom of Kongo from 1506–1543

- Chester A. Arthur, U.S. President

- Otto von Bismarck, German Chancellor

- Roger Casement, Irishman who served as a British representative

- John Dunlop, co-founder of Dunlop Company

- James Cardinal Gibbons, Catholic Archbishop of Baltimore

- Ilanga, resident of Waniendo Village, Congo

- Charles Lemaire, Force Publique officer

- King Leopold II of Belgium, Congo colonizer

- Patrice Lumumba, first elected prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Joseph Mobutu / Mobutu Sese Seko, president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1965–1997

- Edmund Dene Morel British citizen, journalist, and pacifist

- Chief Mulume Niama, Congolese freedom fighter

- Leon Rom, head of the Force Publique

- General Henry Shelton Sanford, U.S. diplomat turned lobbyist for Leopold

- Mary French Sheldon, British travel writer and publisher

- Reverend William Henry Sheppard, African American missionary for the Presbyterian Church

- Henry Morton Stanley (John Rowlands), explorer and colonizer

- Mark Twain, author and member of the Congo Reform Association

- George Washington Williams, African American minister, veteran, and historian

The trial activity includes roles for:

- Capitalism

- Colonial Administrators

- Consumers of Rubber

- Force Publique

- Ilanga, resident of Waniendo Village, Congo

- King Leopold II of Belgium

Classroom Stories

We use so many Zinn Education Project resources. Our favorites are Bill Bigelow’s mock trials about Columbus and Alison Kysia’s on the Congo. The skill development with connecting evidence to arguments is great and the wrestling with the responsibility for these two tragic events is so thought-provoking. The students really get a sense of how difficult it is to assign blame. I especially like the students wrestling with the system as defendants. I am doing the Columbus trial again next week.

The Congo trial is such a new area for students. There is little to no background for most students coming in. I love how the students see the parallels between Columbus and Leopold.

Last year was my first year teaching World History and I was in need of high quality simulations to help my students understand and engage their critical thinking. The Congo, Coltan, and Cell Phones lesson about Belgian rule of the Congo fit nicely into my unit on imperialism and it helped the students exercise empathy with people in the past.

The mixer presents different historical biographies of real and composite figures, and describes their roles as perpetrators or victims of European violence. The lesson was eye opening, and my students rated it highly. Our discussion after the mixer was insightful, with many students commenting on how topics like colonialism and imperialism still impact their daily lives. Overall the discussion was excellent and my students got to explore and interact with the past in a way that felt very meaningful and relevant.

The lesson Congo, Coltan, and Cell Phones worked great in my 12th grade Contemporary World Studies course. I had recently read the great book King Leopold’s Ghost by Adam Hochschild and I wanted to work Belgian atrocities in the Congo — and European colonialism in Africa more generally — into my teaching. This lesson was perfect in that it covered key ideas from history, but also made the story current. The activity is super engaging!

I used Congo, Coltan, and Cell Phones: A People’s History lesson plan. It was absolutely awesome! The students were so engaged in the role play and the trial, and even made comments about how much they learned and enjoyed the lesson. I can’t wait to use it again next year.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn