By William Loren Katz

By William Loren Katz

Before Christmas emerged as a commercial success it led a checkered life. In the 13 colonies it was far from a Silent Night, Holy Night. In Puritan colonies people could be arrested and fined for celebrating. Colonists knew it as a heavy drinking, brawling festival, a raucous blend of July 4th and New Year’s Eve.

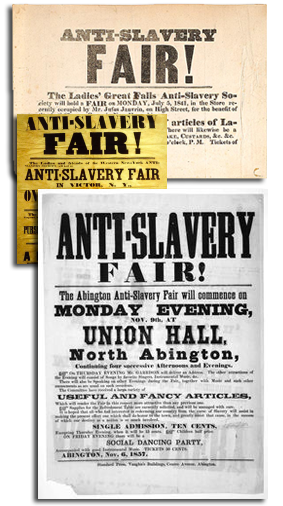

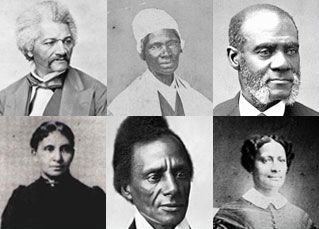

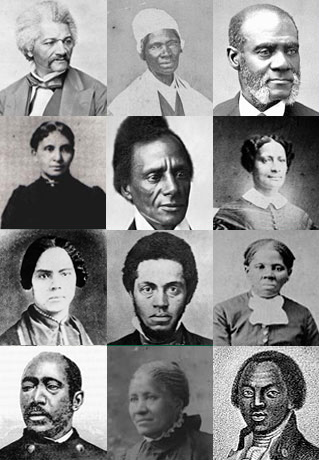

In 1834, men and women — African American and white — of William Lloyd Garrison’s newly formed Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society saw Christmas as an opportunity to expose a republic that proclaimed liberty yet held millions as slaves. Women assumed the lead, boldly defying a society that denied them a public voice or political opinions. To finance the abolition cause, these women organized Christmas bazaars that sold donated gifts, and trumpeted anti-slavery messages in the name of the prince of peace and emancipation.

Because women were prominent, the press labeled abolitionist gatherings “promiscuous assemblies” and denounced male supporters as “Aunt Nancy men.” Then came violence, mob attacks sanctioned by the rich and their media. After some meetings, women linked arms, Black and white, and surrounded their men to protect them from angry mobs. But anti-slavery men and women persisted.

During this Victorian era, women abolitionists also took the lead in confronting a Northern public that felt the degradation of enslaved women and children was too sensitive for public discussion. With clear language and images they used their fairs to show the brutality inflicted on their enslaved sisters.

The women also floated experimental symbols and language. To penetrate the Northern white conscience, they compared the common practice of whipping children — beginning to gain widespread disapproval — to the brutal whipping of enslaved men, women, and children. They used the evergreen shrub as their Christmas symbol.

By the end of the 1830s, Christmas fairs had become the primary source of abolitionist funds.

Women also turned the holiday into a generous, gift-giving Christmas that rewarded children. Their emphasis on children asked Americans to grant that enslaved people, who had even fewer rights than children, deserved Christian care and generosity. This strategy was also designed to challenge slaveholder propaganda portraying enslaved adults as children. At least one early Massachusetts anti-slavery fair featured an interracial children’s chorus known as the Boston Garrison Juvenile Choir, which sang popular holiday songs as “The Sugar Plums.”

By the end of the 1830s, Christmas fairs had become the primary source of abolitionist funds. Bazaar sponsors now replaced the small green shrub with a tall, full-grown evergreen tree. The tree idea was inspired by Charles Follen, a German immigrant, children’s rights advocate, and professor of literature at Harvard University, who had been fired in 1835 because of his anti-slavery activities.

That Christmas, popular British author Harriet Martineau visited Follen’s home and became entranced by his towering evergreen. Martineau enthusiastically described Follen’s “Christmas tree” in one of her books and the public became enthralled. The Christmas tree stood as a kind of tall green freedom flag.

Their early anti-slavery weapons handed Christians today such endearing symbols as the emphasis on children, gift giving, and the tall evergreen.

To expose the country’s greatest crime, challenge its largest vested interest, and persuade fellow citizens their cause was righteous, a daring interracial band of women transformed an antisocial and rowdy festival into a holiday that promoted freedom for all. Shining light on the sins of human bondage and demanding emancipation, pioneer Christian women agitators beat on closed doors.

Eventually, their once lonely crusade helped liberate their Southern brothers and sisters of color and later gave birth to a movement that freed all women. These brave Black and white women gave democracy, and all of us, a Christmas gift that never stops giving.

William Loren Katz is the author of Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage, The Lincoln Brigade: A Picture History, and 40 other books on African American history. Read a profile of Katz and more books and articles by Katz.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn