By William Loren Katz

With family excitement building with the approach of Thanksgiving, you would never know November was Native American Heritage Month. We would do well to recognize Native American resistance to colonialism on Thanksgiving instead of the myths about Native American dinner with Pilgrims.

With family excitement building with the approach of Thanksgiving, you would never know November was Native American Heritage Month. We would do well to recognize Native American resistance to colonialism on Thanksgiving instead of the myths about Native American dinner with Pilgrims.

Thanksgiving remains the most treasured holiday in the United States, honored by the White House since Abraham Lincoln initiated the holiday to rouse northern patriotism for a war that was not going well.

Thanksgiving has often served political ends. In 2003, in the current age of U.S. Middle East invasions, President George Bush flew to Baghdad, Iraq to celebrate Thanksgiving Day with U.S. troops. He sought to rally the public behind an invasion based on lies. A host of photographers came along to snap him carrying a glazed turkey to eager soldiers. In three hours he flew home, and TV brought his act of solidarity and generosity to millions of U.S. living rooms. But the turkey the President carried to Baghdad was never eaten. It was cardboard, a stage prop.

Thanksgiving 2003 had a lot in common with the first Thanksgiving Day. In 1620, 149 English Pilgrims aboard the Mayflower landed at Plymouth, Massachusetts, and survived their first New England winter when the Wampanoag people brought them corn, meat, and other gifts, and taught them survival skills. In 1621, Governor William Bradford of Plymouth proclaimed a day of Thanksgiving—not for his Wampanoag saviors but his brave pilgrims. Through resourcefulness and devotion to God his Christians had defeated hunger.

We are still asked to see Thanksgiving through the eyes of Governor Bradford. But Bradford’s fable is an early example of “Euro think”—a concoction by Europeans that casts their conquest as heroic.

Bradford claims Native Americans were invited to the dinner. A seat at the table? Really? Since Pilgrims classified their Indigenous saviors as “infidels” and inferiors—if invited at all, they were asked to provide and serve and not share the food.

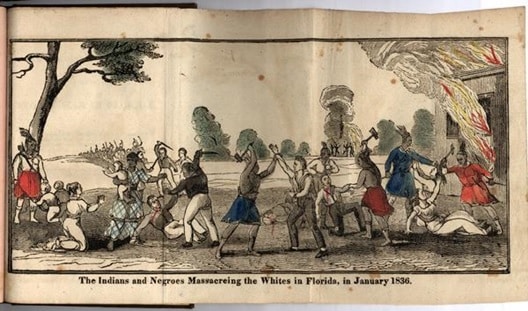

Pilgrim armies soon pushed westward. In 1637, Governor Bradford sent his troops to raid a Pequot village. As devout Christians locked in mortal combat with heathens, Pilgrims systematically destroyed a village of sleeping men, women, and children.

Bradford was overjoyed:

It was a fearful sight to see them frying in the fire and the streams of blood quenching the same and horrible was the stink and stench thereof. But the victory seemed a sweet sacrifice and they [the Pilgrim militia] gave praise thereof to God.

Years later Pilgrim Reverend Increase Mather asked his congregation to celebrate the “victory” and thank God “that on this day we have sent six hundred heathen souls to hell.”

School and scholarly texts still honor Bradford. The 1993 edition of the Columbia Encyclopedia [p. 351] states of Bradford, “He maintained friendly relations with the Native Americans.” The scholarly Dictionary of American History [p. 77] said, “He was a firm, determined man and an excellent leader; kept relations with the Indians on friendly terms; tolerant toward newcomers and new religions….”

Thanksgiving Day celebrates not justice or equality but aggression and enslavement. It affirms the genocidal beliefs that destroyed millions of Native American people and their cultures from the Pilgrim landings to the 20th century.

Americans proudly count themselves among the earliest to fight for freedom and independence. On Thanksgiving, Americans could honor the first freedom fighters of the Americas—those who resisted foreign invasion—but they were not Europeans, and they started long before 1776.

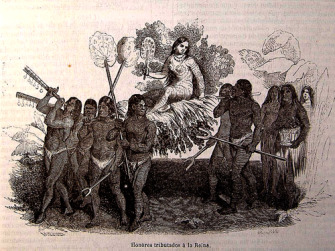

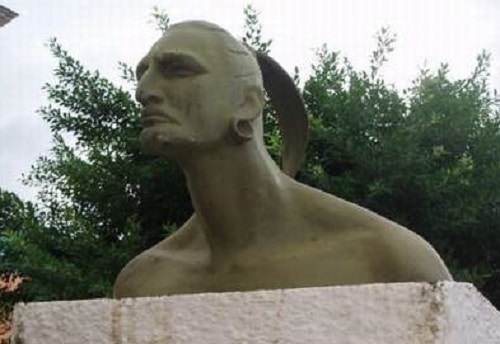

Long before pilgrims landed at Plymouth, thousands of enslaved Africans and Native Americans united to fight the European invaders and slavers. In the age of Columbus and the Spanish invasion, they were led by Taíno leaders such as Anacaona, a woman poet who was captured at 29; and Hatuey, who, in 1511, led his 400 followers from Hispaniola to Cuba to warn of the foreigners, and the next year was captured. Anacaona and Hatuey were both burned at the stake.

Monument to Hatuey in Baracoa, Cuba. |

The Taíno regale Queen Anacaona in an 1851 engraving. Image: Wikipedia. |

Before the Mayflower, thousands of runaway Africans and Indians in northeast Brazil had begun to unite in the Republic of Palmares, a three walled maroon fortress that enabled Ganga Zumba’s 10,000 people of color to defeat Dutch and Portuguese armies. Palmares lasted until 1694, almost a hundred years.

These early freedom fighters kept no written records, but some of their ideas about freedom, justice, and equality found their way into a sacred parchment Americans celebrate each July 4th.

The traditional and logical way to celebrate freedom fighters has been to start with the earliest. Anacaona and Hatuey would tell us Columbus and the Pilgrims do not qualify for anything but condemnation.

—William Loren Katz is the author of Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage, and 40 other books on African American history. More articles and books by Katz. This essay is adapted from the 2012 edition of Black Indians.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn