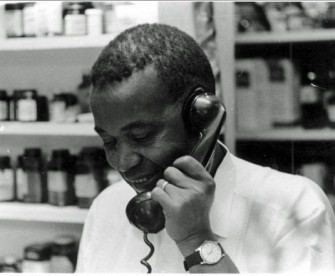

Update: We are sad to share that Ivanhoe Donaldson passed away on April 3, 2016 at the age of 74. Remembrances can be found on CRMvet.org.

On May 27, 2014, students in two U.S. history class at Stuyvesant High School in New York City had the opportunity to talk with Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) veteran Ivanhoe Donaldson. It was a virtual visit, made possible through a collaboration between the SNCC Legacy Project and the Zinn Education Project.

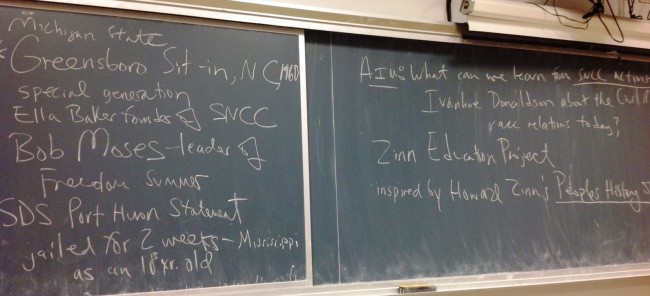

Donaldson began by telling the story of how he got involved in the Movement, inspired by the Greensboro sit-in while he was a student in Michigan. He placed his own activism in the context of being a child and grandchild of the WWII generation.

Challenging the assumption that Jim Crow was just in the South, Donaldson described his Civil Rights Movement activism in Mississippi and Michigan. One of the stories he told was about delivering food in December of 1962 to sharecroppers.

In the early sixties there was a major move by major plantation owners in the delta area of Mississippi to displace, to remove, to discourage activities by blacks who were trying to register to vote. One of the ways in which they created antagonisms was to go to the livelihoods of the sharecroppers and tenant farmers who worked in the cotton plantations in Mississippi. So they moved them off the plantation which took away their ability to survive.

SNCC put out a call for people to bring food. A guy named Ben Taylor and myself collected food in the Ann Arbor area of Michigan and East Lansing. We (SNCC and SCEF) had a major project in Louisville, Kentucky at the time. We went there and used it as a base and we got major truckloads of food and we drove it down to Clarksdale, Mississippi, in Coahoma county where Aaron Henry, the head of the NAACP in Mississippi, had his base in a drugstore. Everyone called him Doc Henry, but he was a pharmacist. Doc was the statewide coordinator and Coahoma was a major disbursing point for food to meet people’s needs.

Ben and I arrived in Clarksdale with a truckload of food in the wee hours of the morning, around 2:00-3:00 a.m. The store was locked and we didn’t remember how to get to Doc’s house so we simply parked the truck in front of the drugstore and cracked the windows and went to sleep. About two or three hours later, around 5:00 a.m., the police woke us up. We were harassed and juggled around and thrown in jail. We were locked up there for about five days before anybody even knew that we were locked up and people knew that we disappeared.

The county jails in Mississippi used prisoners to do local labor. One of the jobs was to collect money out of the parking meters. I met this guy in a bunk beside me who was going to collect money on Fourth Street where Doc’s store is; I gave him a little note—saying, “Doc, I’m in jail, help, Ivanhoe.” About three or four days later he got a message back to us. It eventually became a fairly large case down there. We were gotten out of jail by a writ of habeas corpus by the NAACP Inc. Fund, filed in federal court and we had a $15,000 a piece bail bond. We got beat up a couple of times while we were down there. The charges were based around the concept that we were taking narcotics across state lines, but what we had were aspirins and bandages as parts of first aid kits for people who might need some kind of medical help. [Text based on notes from the conversation and Eyes on the Prize interview.]

Then Donaldson responded to students’ questions and asked the students for their own opinions. Here are two of the many interactions from the class sessions:

Students took turns asking questions of their guest on the screen.

Student: How did you deal with fear?

Ivanhoe Donaldson: The work became more important than the individual.

Student: Which is more important, education or economic reform?

Ivanhoe Donaldson: Values come first. As long we have war, we will not advance. Most important is non-violence. As it says in a Pete Seeger song, “Peace in the world, or the whole world in pieces.”

Here are some student reflections from the session:

My only wish is that it could have been longer. The experience was worth it, by far. It’s incredibly inspiring to be able to listen and talk with someone who was so deeply involved in a movement that seemed to only be in the one-dimensional text of a textbook. One of the most moving quotes Mr. Donaldson said was that “Greensboro touched a nerve.” A strong advocate of peace, Mr. Donaldson told us that even cussing is considered violence.

Topics of the conversation.

I feel like I understood why people would risk their lives for this movement from listening to Mr. Donaldson. It was also interesting to learn that many were arrested and jailed without charges. Overall it was helpful in understanding the context of the movement.

I liked the connections he made between himself and Malcolm X’s brother and how he talked about key historical figures like Dr. Martin Luther King and Ella Baker. He made the movement much more real and one I could relate to, rather than just some story in a textbook.

I have never been part of an activity where we listen to someone from history and get to ask questions. It really was worth the time and something you only experience once in a lifetime. A primary source of the Civil Rights Movement also hypes up the situation because you get the facts straight up.

The non-Hollywood, authentic version of history, in addition to the discussion about civil rights today, was invaluable.

Before the visit, teacher Robert Sandler shared with students the following brief bio of Ivanhoe Donaldson:

Ivanhoe Donaldson worked for SNCC as an organizer and held leadership positions within the organization. In 1960-62, as a SNCC field secretary, Donaldson collected food in Michigan and Kentucky and brought it to Mississippi to help sharecroppers and tenant farmers who had been kicked off of their land for attempting to register to vote.

DANVILLE, Va.—SNCC members Ivanhoe Donaldson, Marion Barry, and James Forman protest police brutality, June 10, 1963. © Danny Lyon/Magnum

In 1963 he was active in demonstrations in Danville, Virginia, and later during “Freedom Summer” in Mississippi in 1964.

After the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) began planning a march from Selma, Alabama, to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1965, Donaldson became one of the SNCC organizers in Selma.

In 1968, Donaldson helped found Afro-American Resources, Inc., which ran the Drum and Spear Bookstore, Drum and Spear Press, and the Center for Black Education in Washington, D.C. He was also a visiting lecturer for Afro-American courses at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst in 1970. Donaldson advised and worked for Washington, D.C. mayor Marion Barry for many years. [Learn more from Eyes on the Prize interview and from Ivanhoe Donaldson’s profile on One Person, One Vote.]

This classroom dialogue with a SNCC veteran was one of three held this spring. In addition to New York, veterans spoke with students in Birmingham, Ala. and Indianapolis. During this decade of historic anniversaries of countless modern Civil Rights Movement milestones, the SNCC Legacy Project and Zinn Education Project hope to continue to provide opportunities for students to learn the history of the voting rights struggle outside of the textbook and discuss the implications for activism today.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn