Howard Zinn wrote extensively about the history of the Civil Rights Movement in his memoir You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times and in SNCC: The New Abolitionists. His writing was informed by his work as a historian, professor, and active participant/adviser with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Here is an excerpt from Chapter 6 of You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train about the 1964 voting rights struggle in Hattiesburg, Miss. It provides a detailed description of the day to day bravery and challenges of voting rights activists — beyond-the-textbook narratives about national demonstrations and iconic leaders.

Howard Zinn wrote extensively about the history of the Civil Rights Movement in his memoir You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times and in SNCC: The New Abolitionists. His writing was informed by his work as a historian, professor, and active participant/adviser with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Here is an excerpt from Chapter 6 of You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train about the 1964 voting rights struggle in Hattiesburg, Miss. It provides a detailed description of the day to day bravery and challenges of voting rights activists — beyond-the-textbook narratives about national demonstrations and iconic leaders.

By Howard Zinn

By Howard Zinn

Mrs. [Fannie Lou] Hamer told me that a few months earlier she and five other movement people had been returning to Greenwood from a meeting in South Carolina. The bus stopped briefly in Winona, Mississippi, and some of them went into the “white” waiting room. They were all arrested, taken to jail, separated from one another. Annell Ponder, a graduate of Clark College in Atlanta (her younger sister was a student of mine at Spelman), was beaten to the point where her face was so swollen she could barely speak. Mrs. Hamer was beaten with blackjacks all over her body.

She reflected, “You know they said outsiders was coming in and beginning to get the people stirred up because they’ve always been satisfied. Well, as long as I can remember, I’ve never been satisfied.” I asked her if she was going to remain with the movement and she responded with the words to a song: “I told them if they ever miss me from the movement and couldn’t find me nowhere, come on over to the graveyard, and I’ll be buried there!”

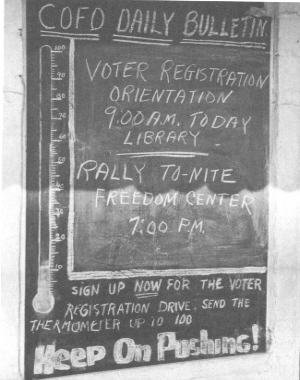

The next time I saw Mrs. Hamer was January 21, 1964. It was Freedom Day in Hattiesburg, in southern Mississippi. SNCC would try to have hundreds of black Mississippians register to vote, in a county where not one black person was registered.

I sat in on the strategy session for Freedom Day. There would be a mass meeting that night, a picket line around the courthouse the next day. There would be arrests, undoubtedly. A telegram was sent to Attorney General Robert Kennedy: “Tomorrow morning, hundreds of Hattiesburg’s citizens will attempt to register to vote. We request the presence of federal marshals to protect them. We also request that local police interfering with constitutional rights be arrested and prosecuted. Signed, Bob Moses.” We all knew there would be no reply.

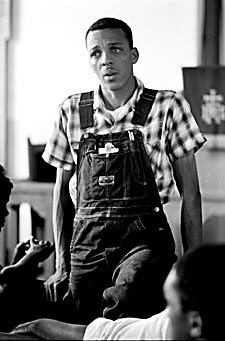

Ella Baker and John Lewis

Ella Baker and John Lewis arrived by train from Atlanta to speak at the church meeting, where a thousand people gathered, singing, “We shall not, we shall not be moved. . . .” The other civil rights groups were represented: Annelle Ponder for Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Dave Dennis for the Congress of Racial Equality. A rabbi spoke, part of a delegation of fifty clergymen who would join the picket line.

Ella Baker spoke, going beyond the immediate, as she always did, to fundamentals: “Even if segregation is gone, we will still need to be free, we will still have to see that everyone has a job. Even if we can all vote, but if people are still hungry, we will not be free. . . . Singing alone is not enough. We need schools and learning. . . . Remember, we are not fighting for the freedom of the Negro alone, but for the freedom of the human spirit, a larger freedom that encompasses all mankind.”

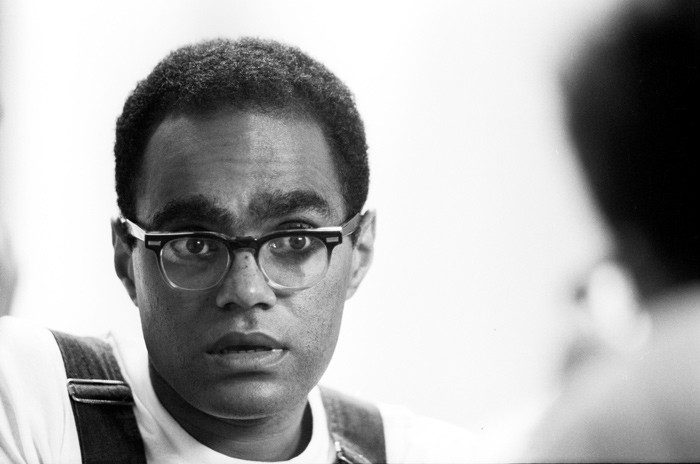

Dave Dennis in 1963. Source: ©Steve Schapiro.

When the meeting was over we all poured out of the building into the darkness. People were still singing. It was almost midnight. There were cots set up at the Freedom House where we would sleep. Over on a long counter a half-dozen people were lettering the picket signs for the morning.

It was 1:00 in the morning, and some of us didn’t feel like sleeping. I was assigned to share a cot with a white SNCC man named Mendy Samstein. We were friends from Atlanta, where he had taught briefly at Morehouse as a young graduate student at the University of Chicago, then left to work with SNCC. We had been together in a strange sit-in that in later years we would laugh about: the two of us and two black friends, sitting in at Leb’s, a Jewish delicatessen in downtown Atlanta, on Passover.

But we found someone already snoring on our cot. Two more guys joined us: Oscar Chase, a Yale Law School graduate then with SNCC (in later years to become a law professor at New York University) and Avery Williams, who still had scars on his leg from the cattle prods in Selma. Someone handed us a slip of paper with an address. It was 3:00 a.m. when we hesitantly knocked on the door of the house, which was all dark. The man who came to the door was in his pajamas. He smiled broadly. “Come on in!” He shouted through the darkness. back into his bedroom. “Hey, honey, look who’s here!” The lights were on now and his wife came out. “Can I fix something for you fellows?” We said no, and apologized for getting them up. The man waved his hand. “Oh. I was going to get up soon anyway.”

The man dragged out a mattress for us. “Here, two of you can sleep on the mattress, one on the couch, and we have a little cot.” I awoke at dawn, and in the semidarkness I could see my friends near me, still asleep. I became aware of the sound that had awakened me: at first I had thought it part of a dream, but I [can] still hear it now, a woman’s voice, pure and poignant, chanting softly.

At first I thought it came from outside, then I realized it was coming from the bedroom. The man was already gone to work, and his wife was praying, intoning, “Oh, Lord Jesus. Oh, let things go well today, Jesus. . . Oh, make them see, Jesus . . . Show your love today, Jesus … Oh, it ‘s been a long time, oh, Jesus . . . Oh, Lord. Oh, Jesus. . . .”

Avery awoke. A radio was turned on with dance music played loud. A light went on in the kitchen. As we dressed I looked through the open doorway into the couple’s bedroom and saw there was no mattress on their bed. They had given us theirs.

The woman made breakfast, a feast — eggs and grits and bacon and hot biscuits and coffee. She told us her husband drove down to the Gulf every morning to work on the fishing docks. She was soon to be picked up in a truck and taken off to work as a maid. As we prepared to leave, Avery Williams looked outside: “It’s raining!”

When we arrived at the county courthouse, a picket line was already formed.

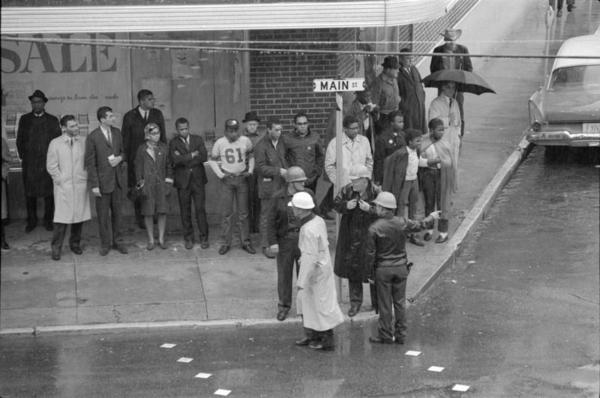

“Riot squad” on January 22, 1964, marching down Pine Street to courthouse where citizens plan to register to vote.

Two lines of policemen came down the street; a police car swung to the curb. A loudspeaker on its roof: “This is the Hattiesburg Police Department. We’re asking you to disperse. Clear the sidewalk.” John Lewis and I stood across the street in front of Sears Roebuck, on the sidewalk. None of us made a move to leave. About fifty black youngsters arrived to join the picket line.

Freedom Day, January 22, 1964, Hattiesburg, Miss., in front of the Sears Roebuck. Participants include: Howard Zinn, third from left; John Lewis, arms crossed, sixth from left; Bob Moses, immediate left of street sign; and James Forman, immediate right of street sign.

People prepared to register were lined up on the steps outside the glass door, which was guarded by a sheriff. The Justice Department had secured a court injunction against discrimination by the registrar. That was as far as they would go. The registrar was complying — minimally. Four people were admitted every hour, the rest having to line up on the steps, exposed to the rain. By noon, twelve people had filled out applications.

A Hattiesburg resident (left) attempts to register to vote on Freedom Day, January 22, 1964. Forrest County Circuit Clerk Theron Lynd (right) was notorious for doing all he could to keep African Americans off the voting rolls.

At 10:00 the drizzle had become a downpour. Jim Forman stood just outside the glass door of the courthouse, shirt collar open under his raincoat, pipe in his right hand, gesticulating with his left hand, black men and women bunched around him. He was calling to the sheriff to ask him to let these people inside the courthouse, out of the rain.

Someone said that Bob Moses had just been taken off to jail, arrested for standing on the sidewalk opposite the courthouse and refusing to move on.

Fannie Lou Hamer picketing on Freedom Day, 1964, in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Photo: © Matt Herron.

The picket line continued all afternoon. I could see the familiar form of Mrs. Hamer, moving along with her characteristic limp, holding a sign, her face wet with the rain and turned upwards, crying out her song against the sky: “Which Side Are You On?” After a while I took the picket sign from her and walked the line while she rested on the steps.

Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker, later in 1964 at a Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party convening. Image: © Johnson Publishing Company.

Later, in the summer of 1964, Mrs. Hamer went to the Atlantic City Democratic Party Convention with other black Mississippians, to demand of the Democratic big-wigs that blacks be represented in what was an all-white Mississippi delegation. She appeared on television to move the nation — if not the Democratic party — with her indignation: “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired!” (She visited me in Boston some time after that, on her way to an audience with Cardinal Cushing, whom she had been briefed to address as ”Your Eminence,” she told me, laughing, that she was afraid she would slip and address him as ”Your Enemy”.)

At 5:00 the picket line at the Hattiesburg courthouse ended. It was something of a victory — no mass arrests, no beatings.

There was one more piece of news. Oscar Chase had been arrested. His car had bumped a parked truck, doing no damage, but that didn’t matter; he was taken off to jail for “leaving the scene of an accident.”

I slept that night in the Freedom House. In the morning someone came along to say that Oscar Chase had phoned in to headquarters from the jail. He had been beaten the night before, and wanted to be bonded out. I went with two of the visiting ministers to get him.

As we entered the jailhouse a few minutes before 8:00 a.m., the police dogs were growling and barking in their kennels. We turned over the bond money.

A moment later, Oscar came down the corridor unescorted. A few moments before, the corridor had been full of policemen, but now there was not a soul around. Oscar was still wearing his badly worn corduroy pants, and his old boots, caked with mud. His blue workshirt was splattered with blood, and under it his T-shirt was very bloody. The right side of his face was swollen. His nose looked as if it were broken. Blood was caked over his eye.

He told us what had happened. They had put a prisoner into his cell who was in a state of great agitation, very upset about the demonstration at the courthouse. He had been a paratrooper in World War II and told Oscar he “would rather kill a nigger lover than a Nazi or a Jap.” He pushed a cigarette near Oscar’s face and said he would burn his eyes out. Oscar called for the jailer and asked to be removed from the cell. The ex-paratrooper asked if Oscar was “one of them nigger-lovers.” The jailer nodded. The next thing Oscar knew he was lying on the floor. He had been unconscious. Now he was being kicked. He was bleeding. The police came and took the ex-paratrooper out of the cell. Oscar made his phone call.

We arranged to take him to one of the two black doctors in town, but first I and two lawyers would show him to the FBI. The four of us waited in the FBI office for the interrogating agent to come out and get the facts about the beating. The two attorneys were impeccably dressed: John Pratt, an attorney with the National Council of Churches, tall, blond, slender, in a dark suit with faint stripes; Robert Lunney, of the Lawyer’s Committee on Civil Rights, dark-haired and clean-cut, attired as befit an attorney with a leading Wall Street firm. I did not come up to their standards (my pants had lost their press from the rain the day before), but I was clean-shaven and not too disreputable-looking.

Oscar Chase, after beating in Hattiesburg. Source: The Nation, 1964.

Oscar sat with us, looking just as he did when I saw him come out of his cell, his face swollen, his clothes bloody. The FBI agent came out from the inner office and closed the door behind him. He surveyed the four of us with a quick professional eye and then asked, “Who was it got the beating?”

At 4:00 that afternoon, the Hattiesburg Municipal Court convened to hear the case of Robert Moses, on trial for obstructing traffic by standing on the sidewalk and refusing to move on when ordered by a policeman. We had decided in advance that we would “integrate” the courtroom, although every previous attempt at that had met with arrests. I sat on the “colored” side with about ten other whites, and an equal number of blacks sat on the “white” side. Nine marshals stood against the wall.

The judge entered the chamber and everyone rose. To our surprise, it was a woman, Judge Mildred W. Norris, a gracious lady who smiled and posed for the photographers as she approached the bench, then nodded for everyone to be seated. She smiled pleasantly at the spectators, paused for a moment, then said sweetly, “Will the marshals please segregate the courtroom?”

Everything was quiet. The marshals moved toward us. The judge said, “I will ask you to please move to the side of the courtroom where you belong, or leave. If you do not, you will be held in contempt of court and placed under arrest.” None of us moved. The marshals came closer.

As one approached me I raised my hand. He stopped and said, rather uncertainly, “Do you wish to make a statement?” “Yes,” I replied. The judge said, “You may make a statement.” I got to my feet and said, “Your honor, the Supreme Court of the United States has ruled that segregated seating in a courtroom is unconstitutional. Will you please abide by that ruling?” The courtroom buzzed. The judge hesitated. John Pratt, the movement attorney, asked for a recess of a few minutes, and the judge granted it.

Robert Moses training Freedom Summer volunteers, 1964. Photo by Steve Schapiro.

During the recess no one changed seats. The judge reconvened the court, and the room was absolutely silent. She surveyed the situation, glanced at the marshals along the wall, and said, “We here in Mississippi have had our way of life for hundreds of years, and I obey the laws of Mississippi. I have asked that you sit segregated or leave or be placed under arrest. We would have appreciated your complying.” She paused. “But since you do not, we will allow you to remain as you are, providing you do not create a disturbance.”

We sat there astonished. The trial began: John Quincy Adams v. Robert Moses (Adams was the arresting officer, and the case came to be called Adams v. Moses). Three policemen took the stand and testified that Moses had obstructed pedestrian traffic by standing on the sidewalk. Cross-examined, John Quincy Adams admitted that no other pedestrians had complained about the sidewalk being obstructed and that he had not seen anyone who did not have free access.

The courtroom was very hot and the judge began fanning herself with a cardboard sign near her. It was one of the exhibits, a picket sign with large letters: “Freedom Now.”

Bob Moses took the stand, to be examined by a bullying prosecutor. He answered in a quiet, even voice, pointing out patiently again and again where the prosecutor had misunderstood his reply, occasionally blinking his eyes under the glare of the lights in the courtroom, but looking steadily, seriously at his questioner.

At the end of the day’s testimony, the judge found Moses guilty, sentenced him to a fine of $200 and sixty days in jail, and Patrolman John Quincy Adams took him back to his cell.

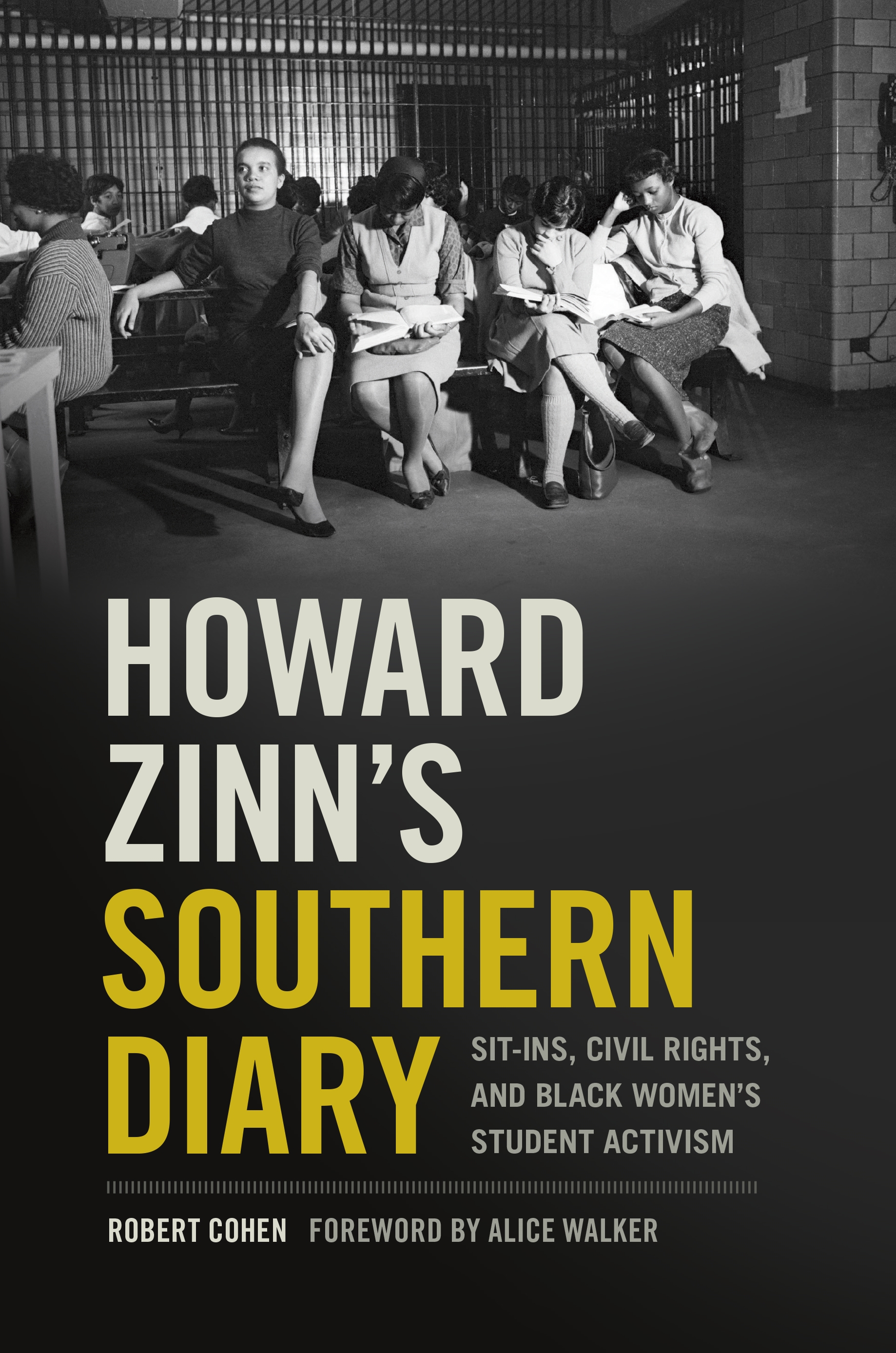

Excerpt from You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times by Howard Zinn (Beacon Press, 2002). This a student-friendly memoir by historian-activist Howard Zinn with stories about his years teaching at Spelman College; his involvement in the civil rights, labor, and anti-war movements; his fight for academic freedom for professors and students; how his experiences growing up in a working class family and in WWII shaped his political perspectives; and more.

The photos, unless otherwise noted, are by Hattiesburg photographer Winfred Harmon Moncrief. More photos can be found in the Winfred Moncrief Collection at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH).

Read more about Freedom Day in Hattiesburg on the Civil Rights Movement Veterans website.

Howard Zinn education project is great. One article a day removes years of blindness.