We are pleased to share this essay by Staughton Lynd in response to one of the recent media attacks on Howard Zinn and A People’s History. These attacks include Sam Wineburg’s “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short” in the American Federation of Teachers’ American Educator magazine and “Agit-Prof: Howard Zinn’s influential mutilations of American history” by David Greenberg in The New Republic. [See responses to the latter here.]

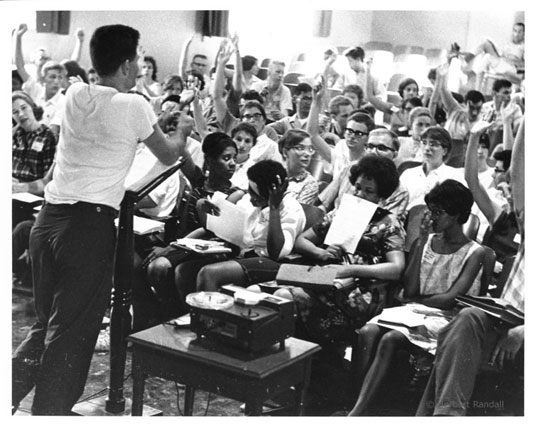

We have long been informed and inspired by Lynd’s decades of scholarship and activism including teaching history from the bottom up, making history with his leadership role in the Freedom Schools and anti-war movement, defending the rights of workers and prisoners, and much more. Lynd knew Howard Zinn since the early 1960s when they taught at Spelman College (in fact Zinn helped Lynd get his job there) where they both supported students active in the Civil Rights Movement.

A People’s History: Supplement or Textbook?

By Staughton Lynd

I think Sam Wineburg’s “Undue Certainty: Where Howard Zinn’s A People’s History Falls Short” can be a springboard for a useful discussion. Unlike some other critiques of Zinn it is a serious contribution. One does not have to fight one’s way through a blizzard of pejorative adjectives to get to what the author is trying to say.

Supplement or Textbook?

So that the busy teacher will know where I am going, here is my thesis. I believe that teachers who try to use A People’s History of the United States typically view it, and present it to their students and school administrators, as a supplement to the conventional mainstream narrative found in the course textbook. It is foreseen that school administrators and parents would be disturbed if the teacher were to ask students to buy and use A People’s History as the course textbook. (My wife and I face the same challenge in teaching history at a nearby prison.) Therefore, I suspect, teachers introduce Zinn’s book as a supplement and defend this practice as an effort to provoke a lively interchange of views and an interest in history that are all too often lacking.

So that the busy teacher will know where I am going, here is my thesis. I believe that teachers who try to use A People’s History of the United States typically view it, and present it to their students and school administrators, as a supplement to the conventional mainstream narrative found in the course textbook. It is foreseen that school administrators and parents would be disturbed if the teacher were to ask students to buy and use A People’s History as the course textbook. (My wife and I face the same challenge in teaching history at a nearby prison.) Therefore, I suspect, teachers introduce Zinn’s book as a supplement and defend this practice as an effort to provoke a lively interchange of views and an interest in history that are all too often lacking.

As Mr. Wineburg puts it: “Many teachers view A People’s History as an anti-textbook, a corrective to the narratives of progress dispensed by the state.” And the problem with his critique is that he seeks to judge A People’s History as if it were a scholarly monograph, in which every assertion is supported by an appropriate footnote.

If, instead, we viewed Zinn’s book as the course textbook, we would find it to be far more scholarly and full of primary sources than the ordinary textbook. This, then, should be our challenge as teachers who see themselves as part of the people’s struggle.

Yes, it would be difficult to tell the principal, “This year I plan to use Zinn as the textbook.” Yes, one would need to spend time and energy to find scholarly work defending Columbus or Andrew Jackson, viewing Lincoln’s relationship to slavery differently (as Eric Foner does), or arguing that Allied military intervention was necessary to stop Hitler. Yes, there could be the same kind of repressive response that Howard encountered at Spelman College and Boston University. But what else is new?

Present-Mindedness

A common criticism of Howard Zinn as an historian is his insistence that we talk about history that is relevant to action we might undertake in response to current political problems. Concern about this aspect of Howard’s work is an undertone in Mr. Wineburg’s commentary. He intimates that because Howard wants students “to better position [themselves] to take action in the present,” Howard wishes us, as a precondition to incisive action, to speak with certainty about the past.

A common criticism of Howard Zinn as an historian is his insistence that we talk about history that is relevant to action we might undertake in response to current political problems. Concern about this aspect of Howard’s work is an undertone in Mr. Wineburg’s commentary. He intimates that because Howard wants students “to better position [themselves] to take action in the present,” Howard wishes us, as a precondition to incisive action, to speak with certainty about the past.

Indeed, in the aftermath of Howard’s death some question was raised as to whether he was really an historian, and more particularly, whether he was able to produce the paradigmatic product of the academic historian: detailed narrative history based on fully cited primary sources. His master’s essay, an account of the Ludlow Massacre in Colorado at the time of World War I, should put that question to rest. It is available in summarized form in Howard’s book, The Politics of History, a source that all commentators on Zinn should read in considering his historical methods.

The detailed rendering of a particular event did not satisfy Howard. He makes this crystal clear at the end of his Ludlow essay, where he writes:

How shall we read the story of the Ludlow Massacre? As another “interesting” event of the past? Or as supporting evidence for an analysis of that long present which spans 1914 and 1970 [the year in which he was writing]. If it is read narrowly, as an incident in the history of the trade union movement and the coal industry, then it is an angry splotch in the past, fading rapidly amidst new events. If it is read as a commentary on a larger question—the relationship of government to corporate power and of both to movements of social protest—then we are dealing with the present. (The Politics of History [Champaign, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1990]: p. 100.)

This approach corrects for a significant deficiency in our work as historians from below. History from below, or as Jesse Lemisch put it, from the bottom up, has too often failed to demonstrate the relevance of our researches about neglected groups to the larger history of the nation and the world, or to the present.

Typically, our work has taken the form of portraying the experience of this or that group of poor and oppressed people at a particular point in the past. Exactly how what we have found challenges mainstream accounts is often not addressed. When this happens, Tom Humphrey has commented, we have “only succeeded in pressing the authors of the master narrative, which largely ignores class and class struggle, to alter their stories slightly or, worse, to add another box for ‘the poor’ on the margins” of the page. The Establishment has been willing to give us the stories of chimney sweeps who get cancer, or seamstresses who burn to death when the foreman locks the door, provided we leave undisturbed the belief that the United States is an exceptionally admirable place, the history of which other societies should do their best to imitate.

Typically, our work has taken the form of portraying the experience of this or that group of poor and oppressed people at a particular point in the past. Exactly how what we have found challenges mainstream accounts is often not addressed. When this happens, Tom Humphrey has commented, we have “only succeeded in pressing the authors of the master narrative, which largely ignores class and class struggle, to alter their stories slightly or, worse, to add another box for ‘the poor’ on the margins” of the page. The Establishment has been willing to give us the stories of chimney sweeps who get cancer, or seamstresses who burn to death when the foreman locks the door, provided we leave undisturbed the belief that the United States is an exceptionally admirable place, the history of which other societies should do their best to imitate.

War

Zinn’s first-hand experience as a World War II bombardier caused him to examine his role in the war, and the impact of war on the world. On a folder that contained his military papers and medals he wrote, “Never again.”

It should go without saying that a concern to make history relevant to the present must not cause the historian to distort the past. Let us consider the theme to which Mr. Wineburg devotes the bulk of his essay, namely, that Howard does in fact distort the past in A People’s History about World War II.

During World War II, Howard Zinn gave up a shipyard job that protected him from the draft in order to volunteer for the Air Force. Found to have aptitude as a bombardier, he traded places with other trainees in order to get into combat sooner. But when he left the military after victory in Europe, Howard wrote “Never again” on the folder that contained his military papers and medals.

What had happened? The eager bombardier has come to feel that no conceivable modern war could be just. It is inevitable that any modern war will involve dropping bombs on civilians and, especially, children, from a height or a distance (as in the case of drones) such that the bombardier cannot see, or hear, or smell, the consequences.

Howard’s last public address was delivered on November 11, the date that used to be called Armistice Day. The text of this speech is available in a collection titled Howard Zinn Speaks, edited by Anthony Arnove (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012), pp. 283–99. It is titled “Three Holy Wars.” Of course Howard meant unholy wars. The three unholy wars were the American Revolution, the Civil War, and World War II.

In this address, Howard criticized what are generally viewed—by historians, including many Left historians, and by the general public—as the three great people’s triumphs of our national history. How, Howard asked, can one criticize events that brought about independence, an end to slavery, and the defeat of fascism? He proceeded to do so.

Enslaved Africans didn’t benefit from the American Revolution. Native Americans lost ground—literally as well as figuratively—because there was no longer a British proclamation attempting to halt westward expansion at the crest of the Appalachians.

Was there a way to become independent without a war? Canada did it. It took Canada longer than the United States to become independent, but “[s]ometimes it takes longer if you don’t want to kill.”

Again, Howard asks of the Civil War if the same result might have been achieved without the deaths of three quarters of a million combatants. (He uses the figure 600,000, which has recently been increased based on the number of “missing males” in census returns.) There is no way to be sure, he concedes. But, he remarks, “slavery was ended in every other country in the Western Hemisphere” without “a bloody civil war.” (Haiti is an exception.)

Again, Howard asks of the Civil War if the same result might have been achieved without the deaths of three quarters of a million combatants. (He uses the figure 600,000, which has recently been increased based on the number of “missing males” in census returns.) There is no way to be sure, he concedes. But, he remarks, “slavery was ended in every other country in the Western Hemisphere” without “a bloody civil war.” (Haiti is an exception.)

Howard ends with what became a characteristic theme at the end of his life, as it is of mine: “When soldiers refuse to fight . . . wars can’t go on.” [Also see Howard Zinn on War.]

World War II

But what about World War II, specifically? Howard’s answer, as he looked back on November 11, 2009, offers the rationale for the account in A People’s History that Mr. Wineburg considers dangerously one-sided and dogmatic. I can’t provide an adequate summary. It’s on pages 294 to 298 of Howard Zinn Speaks. I can give you a taste.

But what about World War II, specifically? Howard’s answer, as he looked back on November 11, 2009, offers the rationale for the account in A People’s History that Mr. Wineburg considers dangerously one-sided and dogmatic. I can’t provide an adequate summary. It’s on pages 294 to 298 of Howard Zinn Speaks. I can give you a taste.

World War II, Howard begins, is still considered “The good war, the best. Fascism. That’s why I enlisted in the air force. . . . They are evil, we are good.”

What caused the eager volunteer to reconsider? One reason was a particular bombing mission in which bombs were dropped on the French town of Royan.

Three weeks before the war was to end, when everybody knew the war was to end and we didn’t need to drop any more bombs, but we dropped bombs on a little town in France. We were trying out napalm. [It was the] first use of napalm in the European theater. . . . And yes, there were really German soldiers there, hanging around. They weren’t doing anything, they weren’t bothering anybody, but they were there. And it gives us a good excuse to bomb. We’ll kill the Germans. We’ll kill some Frenchmen, too. What does it matter? It’s a good war. We’re the good guys.

Mr. Wineburg faults Howard for his failure to use primary sources, or for using primary sources that he finds in the books of other historians. It seems to me that Howard’s own experience as a bombardier in a war that devastated Dresden, killed 600,000 German civilians when industrial cities were deliberately targeted, and used Royan as an opportunity to experiment with napalm, was about as “primary” as one can imagine.

And the experience of disillusionment that Howard describes is not an experience of oversimplifying, of moralizing of the sort that concerns Mr. Wineburg. It is the opposite: an experience of breaking free from the oversimplifications with which every nation clothes its foreign adventures. “[Y]ou don’t think. It’s hard to think when you’re in military. It’s hard to sit back and examine, ask what you’re doing.” It’s so important, Howard pled with his audience of young people, not to say only “Oh, we won.” Fifty million people were dead in that war to end all wars, to end fascism and dictatorship and militarism. And fascism, racism, and militarism were not dead.

A B-29 over Osaka, Japan on June 1, 1945.

Howard Zinn was not personally involved in the bombing of Hiroshima. Like myself, he came to appreciate what had happened there when he read John Hersey’s book Hiroshima. But, Howard adds, he did investigate. He says: “Our own official investigative team, the Strategic Bombing Survey, which went into Japan right after the war, interviewed all the high Japanese civilian and military officials. Their conclusion was Japan was ready to end the war. Maybe not the next week. Maybe in two months, maybe in three months.”

Does Howard misrepresent the conclusions of the Survey? Probably not because he quotes it: “[C]ertainly prior to 31 December 1945, and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered.” (A People’s History of the United States, 1999 edition, p. 402.) Does Mr. Wineburg have a better primary source? It seems that in his view unless a statement displays cautious ambiguity, beginning with the words “On the one hand,” it can’t be real history.

Once Again, Could A People’s History Be a Textbook?

Mr. Wineburg appears to believe that unless we watch out, most high schools and colleges in the country will begin to use A People’s History as their “dominant narrative.” It would be interesting to have some evidence on this point. I would like to know how many high school and college history classes in the United States use Howard Zinn’s book as their principal textbook.

If there were more history classes that did so, we might have an Army abroad that did not burn the Koran or urinate on dead enemies. I was part of a citizens’ jury in Tacoma, Wash., that considered 1st Lt. Ehren Watada’s refusal to fight in Iraq. The very distinguished witnesses included Daniel Ellsberg. The one who sticks in my mind had been an ordinary soldier. He said what happened in Iraq was that you set up checkpoints, and as cars with Iraqi drivers came toward you, speaking a different language, responding to different hand signals, you tried to decide whether the driver was a suicide bomber.

One day a young American guessed wrong, pressed the butterfly trigger on his weapon, and killed the driver, his wife, and two young children. That evening the unit discussed what had happened. After a while the highest ranking officer in the room, some sort of colonel, ended the meeting with the words: “If these fucking hajis would learn to drive, things like this wouldn’t happen.”

We need you, Howie. Howard Zinn, presente.

____________________________________________________

Staughton Lynd taught history at Spelman College and Yale in the 1960s and coordinated the hugely successful Freedom Schools during the Mississippi Summer Project of 1964. After moving to New Haven, Lynd became a spokesperson for opponents of the Vietnam War. As a result of these activities, Lynd was denied work as a university professor and he and his wife became lawyers. Since 1976 they have lived in Youngstown, Ohio, working with and representing local victims of deindustrialization, and prisoners confined at Ohio’s first super-maximum security prison. Read more in From Here To There: The Staughton Lynd Reader.

An autobiography that’s auctally worth reading Let’s face it. Most autobiographies are ego-massaging personal recollections that shed little light on what makes the author tick. But this book represents what an autobiography should be, because it covers Zinn’s political history and how his political and historical views have shaped his life. So in reading this book, we not only know something about Zinn, we learn a great deal about the history of the United States over the past 50 years. To the extent Zinn discusses his personal history, it is usually in the context of his political education, for example, working at Brooklyn shipyards as a youth or flying airplanes in World War II or teaching college in the South during the early 1960 s. These personal events shape Zinn’s views on labor, war and civil rights. Like Forrest Gump, Zinn was there during the 20th Century’s most important events. He has lived an extraordinary life and his views on history deserve the greatest respect. Read this book to see what a real autobiography should look like.

I used A People’s History for years as the primary text in my U.S. History classes in high school. I was, and am still, the only National Board Certified secondary social studies teacher in my district. Two years before I was forced into retirement I was told not to use Zinn and then all my U. S. history classes were taken from me. I still use Zinn in my history classes at our local community college without any administrative interference…yet.

I once tutored a young man in South Park, Colorado, and this young man became interested in A People’s History. When he was found not to have risen for the playing at an assembly of the National Anthem, he became suspect. When the young man was discovered by one of the directors of the Lunch Team to be reading Zinn, he was ordered to appear before the principal. At the meeting, he was presented with a photo-copy of a Wikipedia description of Zinn’s politics as leaning toward “non-violent resolution of conflict” and asked how one could defend this potentially dangerous position.

In short, the book did not become the dominant narrative of the school.