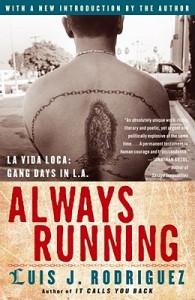

The award-winning and bestselling classic memoir about a young Chicano gang member surviving the dangerous streets of East Los Angeles, now featuring a new cover.

The award-winning and bestselling classic memoir about a young Chicano gang member surviving the dangerous streets of East Los Angeles, now featuring a new cover.

Winner of the Carl Sandburg Literary Award, hailed as a New York Times notable book, and read by hundreds of thousands, Always Running is the searing true story of one man’s life in a Chicano gang — and his heroic struggle to free himself from its grip.

By age twelve, Luis Rodriguez was a veteran of East Los Angeles gang warfare. Lured by a seemingly invincible gang culture, he witnessed countless shootings, beatings, and arrests and then watched with increasing fear as gang life claimed friends and family members. Before long, Rodriguez saw a way out of the barrio through education and the power of words and successfully broke free from years of violence and desperation.

Achieving success as an award-winning poet, he was sure the streets would haunt him no more — until his young son joined a gang. Rodriguez fought for his child by telling his own story in Always Running, a vivid memoir that explores the motivations of gang life and cautions against the death and destruction that inevitably claim its participants.

At times heartbreakingly sad and brutal, Always Running is ultimately an uplifting true story, filled with hope, insight, and a hard-earned lesson for the next generation. [Publisher’s description.]

ISBN: 9780743276917 | Touchstone

Excerpts

One day, my mother asked Rano and me to go to the grocery store. We decided to go across the railroad tracks into South Gate. In those days, South Gate was an Anglo neighborhood, filled with the families of workers from the auto plant and other nearby industry. Like Lynwood or Huntington Park, it was forbidden territory for the people of Watts.

My brother insisted we go. I don’t know what possessed him, but then I never did. It was useless to argue; he’d force me anyway. He was nine then, I was six. So without ceremony, we started over the tracks, climbing over discarded market cars and tore-up sofas, across Alameda Street, into South Gate: all-white, all-American.

We entered the first small corner grocery store we found. Eerything was cool at first. We bought some bread, milk, soup cans and candy. We each walked out with a bag filled with food. We barely got a few feet, though, when five teenagers on bikes approached. We tried not to pay attention and proceeded to our side of the tracks. But the youths pulled up in front of us. While two of the stood nearby on their bikes, three of them jumped off theirs and walked over to us.

“What do we got here?” one of the boys said. “Spics to order — maybe with some beans?”

He pushed me to the ground; the groceries splattered onto the asphalt. I felt melted gum and chips of broken beer bottle on my lips and cheek. Then somebody picked me up and held me while the others seized my brother, tossed his groceries out, and pounded on him. They punched him in the face, in the stomach, then his face again, cutting his lip, causing him to vomit.

I remember the shrill, maddening laughter of one of the kids on a bike, this laughing like a raven’s wail, a harsh wind’s shriek, a laugh that I would hear in countless beatings thereafter. I watched the others take turns on my brother, this terror of a brother, and he doubled over, had blood and spew on his shirt, and tears down his face. I wanted to do something, but they held me and I just looked on, as every strike against Rano opened me up inside.

They finally let my brother go and he slid to the ground, like a rotten banana squeezed out of its peeling. They threw us back over the tracks. In the sunset I could see the Watts Towers, shimmers of 70,000 pieces of broken bottles, sea shells, ceramic and metal on spiraling points puncturing the heavens, which reflected back the rays of a falling sun. My brother and I then picked ourselves up, saw the teenagers take off, still laughing, still talking about those stupid greasers who dared to cross over to South Gate.

Up until then my brother had never shown any emotion to me other than disdain. He had never asked me anything, unless it was a demand, an expectation, an obligation to be his throwaway boy-doll. But for this once he looked at me, tears welled in his eyes, blood streamed from several cuts — lips and cheeks swollen.

“Swear — you got to swear — you’ll never tell anybody how I cried,” he said.

I suppose I did promise. It was his one last thing to hang onto, his rep as someone who could take a belt whipping, who could take a beating in the neighborhood and still go back risking more — it was this pathetic plea from the pavement I remember. I must have promised.

. . . .

First day of school.

I was six years old, never having gone to kindergarten because Mama wanted me to wait until La Pata became old enough to enter school. Mama filled out some papers. A school monitor directed us to a classroom where Mama dropped me off and left to join some parents who gathered in the main hall.

The first day of school said a lot about my scholastic life to come. I was taken to a teacher who didn’t know what to do with me. She complained about not having any room, about kids who didn’t even speak the language. And how was she supposed to teach anything under these conditions! Although I didn’t speak English, I understood a large part of what she was saying. I knew I wasn’t wanted. She put me in an old creaky chair near the door. As soon as I could, I sneaked out to find my mother.

I found Rano’s class with the mentally disabled children instead and decide to stay there for a while. Actually it was fun; they treated me like I was everyone’s little brother. But the teacher finally told a student to take me to the main hall.

After some more paperwork, I was taken to another class. This time the teacher appeared nicer, but distracted. She got the word about my language problem.

“Okay, why don’t you sit here in the back of the class,” she said. “Play with some blocks until we figure out how to get you more involved.”

It took her most of that year to figure this out. I just stayed in the back of the class, building blocks. It got so every morning I would put my lunch and coat away, and walk to my corner where I stayed the whole day long. It forced me to be more withdrawn. It got so bad, I didn’t even tell anybody when I had to go to the bathroom. I did it in my pants. Soon I stunk back there in the corner and the rest of the kids screamed out a chorus of “P.U.!” resulting in my being sent to the office or back home.

In those days there was no way to integrate the non-English speaking children. So they just made it a crime to speak anything but English. If a Spanish word sneaked out in the playground, kids were often sent to the office to get swatted or to get detention. Teachers complained that maybe the children were saying bad things about them. An assumption of guilt was enough to get one punished.

A day came when I finally built up the courage to tell the teacher I had to go to the bathroom. I didn’t quite say all the words, but she got the message and promptly excused me so I didn’t do it while I was trying to explain. I ran to the bathroom and peed and felt good about not having that wetness trickle down my pants leg. But suddenly several bells went off and on. I hesitantly stepped out of the bathroom and saw throngs of children leave their classes. I had no idea what was happening. I went to my classroom and found nothing. Nobody. I didn’t know what to do. I really thought everyone had gone home. I didn’t even bother to look at they playground where the whole school had been assembled for the fire drill. I just went home. It got to be a regular thing there for a while, me coming home early until I learned the ins and outs of school life.

Not speaking well makes for such embarrassing moments. I hardly asked questions. I just didn’t want to be misunderstood. Many Spanish-speaking kids mangled things up; they would say things like “where the beer and cantaloupe roam” instead of “where the deer and antelope roam.”

That’s the way it was with me. I mixed up all the words. Screwed up all the songs.

. . . .

At 16 years old, Rano turned out much better than me, much better than anyone could have envisioned during the time he was a foul-faced boy in Watts.

When we moved to South San Gabriel, a Mrs. Snelling took a liking to Rano. The teacher helped him skip grades to make up for the times he was pushed back in those classes with the retarded children.

Mrs. Snelling saw talent in Rano, a spark of actor during the school’s thespian activities. She even had him play the lead in a class play. He also showed some facility with music. And he was good in sports.

He picked up the bass guitar and played for a number of garage bands. He was getting trophies in track-and- field events, in gymnastic meets and later in karate tournaments.

So when I was at Garvey, he was in high school being the good kid, the Mexican exception, the barrio success story—my supposed model. Soon he stopped being Rano or even Jose. One day he became Joe.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn