Maria Gunnoe and Larry Gibson on the EPA steps, Appalachia Rising, September 2010. Source: David Novack.

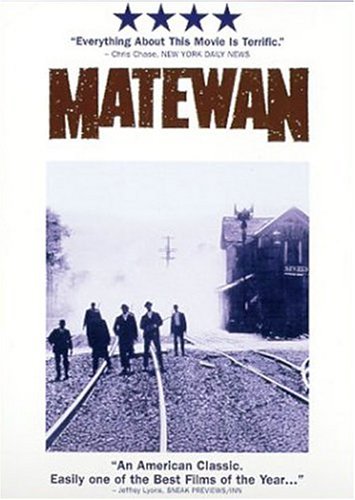

In 30 years of teaching, I’d never taught explicitly about coal. Coal appeared in my social studies curriculum solely as a labor issue. We read passages about the 1914 Ludlow Massacre of striking coal miners and their families in Colorado, and watched John Sayles’ excellent film Matewan when we looked at early 20th-century labor struggles. But coal was mostly invisible in my history classes. At the risk of sounding melodramatic, the world cannot afford this kind of curricular invisibility today. Forty percent of the main greenhouse gas produced in the United States, carbon dioxide, comes from burning coal for electricity; so does two-thirds of all the sulfur dioxide pollution.

According to the American Lung Association, coal is responsible for thousands of premature deaths every year. Almost 40 percent of this country’s electricity comes from burning coal: a billion tons of coal every year — more than 15 pounds of coal burned each day for every person in the United States. And most coal mining in the United States these days is strip mining — the Earth is essentially skinned alive to get at the coal seams within.

According to the American Lung Association, coal is responsible for thousands of premature deaths every year. Almost 40 percent of this country’s electricity comes from burning coal: a billion tons of coal every year — more than 15 pounds of coal burned each day for every person in the United States. And most coal mining in the United States these days is strip mining — the Earth is essentially skinned alive to get at the coal seams within.

Coal companies have sliced the tops off 500 mountains in Appalachia and dumped the waste in the valleys, burying 1,200 miles of streams and poisoning residents’ water. The term for this is mountaintop removal, and it’s not a metaphor.

So I decided that it was time to break my curricular silence on coal.

In this teaching activity, students have the opportunity first to play and later to analyze a game created by The American Coal Foundation. In this way they learn to think critically about the coal industry’s motives and goals. By writing creatively from the perspective of the coal-mining environment, its residents, and environmental activists, and by watching excerpts from films portraying the effects of U.S. coal mining after playing the game, students also expand their contextual knowledge of coal mining and its consequences.

This teaching activity was originally published by Rethinking Schools and is included in A People’s Curriculum for the Earth.

This teaching activity was originally published by Rethinking Schools and is included in A People’s Curriculum for the Earth.

Classroom Stories

Students learning about coal mining with an activity from @ZinnEdProject. We mined the “coal” today, and will discuss the environmental/ethical and political considerations later this week. pic.twitter.com/Xr9pADX3sX

— Brian Bigioni (@MrBigioni308) June 11, 2019

I used the Coal, Chocolate Chip Cookies, and Mountaintop Removal lesson most recently with a group of mostly 9th grade Earth & Environmental Science students.

My high schoolers pointed out how the activity shows that mining and reclamation are seemingly equal processes, according to amounts of time, even though reclamation of land post-mining would actually be a lengthy and sometimes impossible project. One student shared how silly that thought was, “You can’t just gather the crumbs and stick them back, those are plants and animals and homes and peoples livelihoods.” It was easy for them to connect this to environmental issues on water and erosion, how the loose crumbs would actually travel everywhere (as they actually did for some of the students), carrying valuable land away as well as any toxins they picked up.This led us into a natural conversation about other waste products from coal beyond mining, something missing from the cookie activity, which was very pertinent in my North Carolina classroom, where a coal ash spill had recently taken place. We coupled the activity with watching clips from Coal Ash Stories, a compilation of six short films that illustrate the public health concerns and community response to this byproduct.

To note, I modified the activity on two different occasions with inclusion classes (and might do the same in elementary classes). In one class, students got to choose whichever type of cookie they’d like and we just focused on the money related to their mining success and the reclamation. This still allowed us to compare how mining affects different land types and still talk about the destruction and reclamation of the land, as well as what the simulation didn’t show. I also tried it once using “play money” as in the original plans and without the actual calculations sheet, which was more tangible and easier for several students. Both methods were effective in helping all the students in the classroom participate without having to keep track of calculations on a separate paper.

“we all live in a burning coal mine”

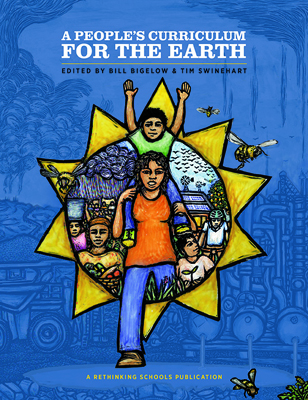

Also see these books for background:

To Save the Land and People: A History of Opposition to Coal Surface Mining in Appalachia

and

A People’s History of Environmentalism in the United States