On December 18, journalist and author Norman Solomon joined Rethinking Schools editor and high school teacher Jesse Hagopian to discuss how Solomon’s book, War Made Invisible: How America Hides the Human Toll of Its Military Machine, relates to coverage of current events in Palestine-Israel, and strategies for teaching media literacy. As the Rethinking Schools editors note,

Norman Solomon begins his fine book, War Made Invisible, with a discussion of propaganda — which requires repetition, repetition, repetition. Think, for example, of the everywhere-present term “defense spending.” In his book, Solomon targets the media and the political establishment, but educators also should take his critique to heart. Too often, our curriculum “makes war invisible.” Too often, the ravages of U.S. militarism go unexamined in our classes. This excellent, fact-filled book insists: Teach about this; people’s lives depend on it.

This workshop was offered as part of our Teaching for Black Lives campaign.

Event Recording

Recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): I am pleased to welcome Norman Solomon, journalist and author of many books, including the one we’re going to focus on this evening, War Made Invisible: How America Hides the Human Toll of Its Military Machine. Norman, thank you so much for joining us this evening.

Norman Solomon: Well, I’m so glad to be part of this session.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Right on. I’ve just been really enjoying your book and finding it so rich to think about using the examples you give in the classroom and thinking about how to teach our students media literacy skills, and also how to help them understand U.S. foreign policy better — it’s just such a treasure trove of information. I just thought I’d begin with something that you wrote, because you write in it that “in the United States, nationalism masquerades as journalism.” I love that line. Can you share some examples of how you see that happen? And do you think that nationalism also masquerades as education?

Norman Solomon: A lot of it is so routine that we don’t really give it a second thought. It sort of blends into the scenery. If a news reporter refers to us as America, in the world the perspective is what we are doing on different parts of the planet. And then the specifics, there’s a couple that come to mind offhand. We tend to think of or are encouraged to perceive the venerable journalist Walter Cronkite as the epitome of good journalism. But there’s footage of him on CBS. And, of course, then there were only three channels during the Vietnam War to speak of. He would get off a jet bomber and say on camera, on CBS Evening News, “That’s a great way to fight a war, general.”

Or you fast forward a few decades and you have Dan Rather also on CBS Evening News, pumping the hand of a general and saying, “Congratulations on a job well done.” Or, during the so-called “shock and awe” with the bombing of Baghdad during the invasion of Iraq in March of 2003, where, on NBC and the other networks, we had these remarkable statements from journalists saying “it was like a tremendous light show.” Or we had reporters, anchors like Katie Couric telling the viewers — millions of them — that Operation Desert Storm had been virtually flawless. Well, we had hundreds of people who were incinerated in one attack on Baghdad in a bomb shelter, who were civilians literally burned alive. And yet you have that sort of nationalism that comes to the fore that says, in effect, that any untoward or negative event that the United States is part of is an anomaly. and anything bad that happens that we can be attributed to as the U.S. government, that is an anomaly. The default is that we mean well, we do well, and that’s what we do in the world right now.

Perhaps more than at any time in our lifetimes, educators are on the frontline. Many journalists, especially in the United States, are keeping their heads down. They’re running for cover. And we know there are all too many instances where teachers who were having the temerity to teach history or refer to current events in a matter of fact, accurate way, are under pressure. I think it’s doubly important for us to recognize that nationalism is a way of polluting the terrain through which we walk as people, as human beings, and it separates us. So, to sum up, whether it’s journalists, whether it’s teachers, we have the challenge to go higher than simple nationalism, to say that we’re on a planet with seven or eight billion people and our fates are intertwined.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): That’s absolutely right. I just love the way you reveal the humanity of the people that those nationalistic narratives hide. My mom helped to work on the study that showed how many excess deaths were a product of the war in Iraq, and it really drove home for me the mass death that was caused by our government, that was often just hidden by the media. In one of the epigraphs in War Made Invisible, in your book, you quote Aldous Huxley, written in 1936, “The propagandist’s purpose is to make one set of people forget that a certain other set of people are human.” I was hoping you could address how you see that happening right now with the situation in Gaza.

Norman Solomon: Unfortunately, there’s a hierarchy of empathy in U.S. media coverage, with some exceptions. As I stress in the first chapter of War Made Invisible, the essence of propaganda is repetition, it’s not what’s exceptional. I give an example, including to young people, when I speak to folks that if you watch a lot of TV, you don’t just see one McDonald’s commercial. If you watch a lot of TV, you see a lot. That’s because it’s about repetition. So, the ways in which human beings, who, in this case, are being terrorized frankly, as well as maimed and sometimes killed, with the help of U.S. military aid, they’re largely objectified and there’s an arm’s length tone and distancing that takes place.

The problem in this instance, I believe, is not that there is empathy towards the Israelis who were killed on October 7th. Of course, there should be complete empathy and condemnation for the terrible killing of those civilians. What’s imbalanced is the relative lack of empathy, of humane and human connection. And let’s face it, we have no way of knowing about people in Gaza right now except through journalism. Just in the last few days, again we’re told through news media in the United States, in a sort of passive voice way, that communications have not been functioning for the last few days. So, it’s even impossible, when an outlet like NPR wants to talk to a doctor in a hospital in Gaza, they’ve lost touch with a doctor for a few days. It didn’t happen as an act of God that there’s no communication in Gaza. These are actions taken by the Israeli Defense Forces, and we have to look at words like defense. It’s advertising. Just like the U.S. Defense Department, the Israeli Defense Forces really is that what they’re engaged in. They’ve made a choice to cut off communication in Gaza because basic information about what’s happening to human beings is a threat.

So, it goes back to that principle that Aldous Huxley was alluding to way back in 1936, which is, if we can distance ourselves or we are induced to distance ourselves from the humanity of certain others, then all kinds of atrocities become possible.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Yeah, they do. I mean, it’s breaking my heart every day to see what’s happening in Gaza, the bombing of hospitals, the bombing of schools, the killing of journalists who are trying to actually get some truth out about what’s happening. So that quote, I think, is just so critical to help us understand how that is allowed to occur. So, thank you for bringing that to our attention. I wanted to expand the lens a little bit, because you quote the brilliant writer Viet Thanh Nguyen, who wrote that, “The severity of anti-Black racism is inseparable from the endurance of American imperialism.” So, I was hoping you could elaborate on the linkage between anti-Black racism, imperialism, and militarism.

Norman Solomon: I grew up around Washington D.C. during the 1960s, when I was in high school. I learned a lot, not per se from the media. As a matter of fact, I learned very little from reading the Washington Post every day in terms of what was happening. But I learned a lot from music, and I learned a lot from lyrics of music, and I learned a lot from talking to people and listening to people. When I learned that there was an encampment in Washington called Resurrection City, as a 16 year old, I went down there. I subsequently learned about the vision of a Poor People’s Campaign.

Then, two decades later, with the [Jesse] Jackson campaigns of 1984 and 1988, that vision of a Rainbow Coalition is a humanistic vision about what can be created in this country and the world. After the murder of George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter movement was very clear about solidarity with people around the world. If the 20th century issue was the issue of the colorline, the 21st century is also an issue of the colorline, and not only in the United States. As a matter of fact, that gets to the broader lens that we’re talking about, the planet. This is another hot button issue and it’s hidden in plain sight.

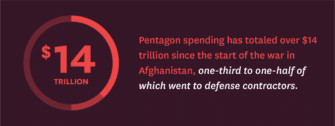

The so-called “war on terror” since October of 2001, with the initial attack on Afghanistan. When we step back and think about it, and look at the data coming from the Brown University’s Costs of War Project, for instance, the reality is that of all the people killed by Pentagon fire power in the last 22 years or so, virtually all of them are people of color. Yet we cannot find that talked about in U.S. news media or on Capitol Hill. That is a hot stove topic that is not touched, even if people were aware of it. And yet, in the last few years we’ve heard more and more, certainly in the last several years, about systemic racism. We’ve heard more about it. Not nearly enough, but it’s been a real step forward in terms of public discourse. Yet, somehow, we’re encouraged to believe that systemic racism stops at the water’s edge, that it only affects domestic government policy, it only affects institutions with purview and power over the United States internally. But, of course, that’s absurd. It’s the same institutions, the same power blocks, and the same individual biases and trainings that have a view on the world.

And I think it’s important to emphasize that the United States does not bomb countries because they’re inhabited by people of color. But when those countries are inhabited by people of color, it makes it easier for the U.S. government to engage in warfare on those countries, for all the same reasons that we have these pernicious and ongoing overt and covert aspects of institutionalized racism in the United States — from educational institutions to media to the so-called justice system to the prisons and the jails. I think we have an opportunity, it’s not just a teaching moment, it’s a teaching decade to say we can now look at systemic racism and systemic bias in a deep way and a wide way and understand not only the role of power centers within our country but the role of the power centers based in the U.S. for much of the rest of the world.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Yes, thank you so much for making those connections. It’s like Muhammad Ali, who refused to be drafted into the war in Vietnam, who said, “No Vietnamese ever called me the n word. My fight is right here at home.” We need to start making those connections again today when we look at how much the U.S. is spending to supply Israel with the weapons that are perpetrating the destruction of so many lives in Gaza. Thank you for that.

I want to ask you another question before we move to some video clips to have you comment on. In your book you write about the protracted silences and the power of omissions that allow U.S. war-making to go unchallenged. What are some of the key silences and omissions in our media and in our schools today?

Norman Solomon: The silences are just so important because they tell us tacitly what doesn’t matter, and about the people who don’t matter and the events that don’t matter. A lot of this is a convenient amnesia, I think. For instance, say Dick Cheney, he’s been rehabilitated largely. He was greeted with open arms a year after the January 6th attack on the Capitol by Democrats and Republicans alike on Capitol Hill. We’ve had so many instances of people engaged from the top ordering aggression on another country, which, according to the Nuremberg Tribunal judgment, was the supreme international crime.

And yet we had Ellen DeGeneres, we had Michelle Obama, making a point of saying that George W. Bush — the former president who had launched that war based on lies — that actually he was their friend, that they had the same values. We were told, “we have the same values, we just have different politics.” Well, what is the value of saying it’s okay to attack another country based on deception, violating international law, causing so much death and destruction? So, I think the silences are just so powerful, and it’s in ways that are omissions. Paradoxically, you can have silences by commission, because talking around it, making nice with those who actually should have been called to account and perhaps put on trial, that’s a way of saying it doesn’t really matter. All those Americans who died in Iraq and Afghanistan? No big deal. The people who live there in much later numbers, dying? No big deal.

And it’s also prefigurative, preemptive, because it’s saying if we can forgive Dick Cheney and George W. Bush, and hold them up as actual paragons of virtue, then when something like this might happen again not only will those leaders not be called to account or be prosecuted, but they will be held up in the future. So, it’s the annihilation, you might say the preemptive annihilation of history — saying history won’t matter. There is an Orwell 1984 aspect of this. I do think that part of the role of authentic journalists and authentic educators is to break the silence.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Yes, I hope everyone on this call will be breaking the silence with us in their classrooms this week, and in the weeks and months to come. Thank you for that framework. I want to look at some clips from the media that deal with the current attacks by Israel on Gaza, and I want to look at it from various perspectives because media literacy has always been something that’s important to me in my classroom. I’ve taught elementary/middle for ten years at my alma mater, Garfield High School here in Seattle. A big focus in my classroom was helping students understand that every document that we read or video that we saw all had a thesis, and that that thesis was being created by someone who had an opinion and a viewpoint on the world. I wanted them to not passively receive that information but actually analyze what is the argument in this text and do I agree with the argument in this text? So, I would often have students create a t-chart when we watched a video, and on one side of the chart they would write what they saw, and the other side they would write what they heard. And they would talk about how the images and the oral arguments put together a thesis and try to identify what that thesis was. So, that’s one strategy I could recommend for educators today.

But let’s play these clips and then I would love to get your comment on what’s going on with these clips and how educators could use them. We’ll start with this one from the nightly news.

Good evening and welcome everyone. We’ll show you some of what we saw in Ashkelon, close to Gaza earlier. But we start here in Tel Aviv tonight, where for six days now the world has watched and waited for the full might of the Israeli response to the horrific attacks inflicted on it, anticipated by many to be a massive invasion of the Gaza strip, making good on its promise to destroy Hamas after last Saturday’s brutal terrorist rampage in Southern Israel.

The toll keeps getting worse. 1,300 in Israel now reported killed; more than 1,500 lives lost in Gaza as Israel steps up its bombing. At least 27 Americans have been killed. And the fate of as many as 150 hostages, including some Americans, remains uncertain tonight. Secretary of State Antony Blinkin, who was here today, says the U.S. is doing everything it can to secure their release. I pressed him on it when we spoke one on one. As the humanitarian crisis in Gaza deepens, a UN agency estimates 340,000 Palestinians have been displaced as Israel’s air campaign intensifies.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): And now we’ll see from the same time period, the same same day, another news clip from Democracy Now!

[Amy Goodman] Welcome to Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, the War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman/ Gaza’s humanitarian crisis is deepening as Israel continues to pummel the besieged Palestinian territory with air and artillery attacks for a sixth straight day, reducing whole neighborhoods to rubble. Gaza’s Ministry of Health says Israel’s attacks have killed more than 1,350 Palestinians and wounded more than 6,000. More than 320 children are among the dead. Survivors have been seen searching the rubble of their homes for lost possessions and food.

[Displaced Gazan speaking] We left our homes thinking we would return in an hour. We left our belongings, money, food, and everything we owned. Now there are 50 people left homeless without food, drink, water, or electricity. I do not know how we will provide food for our children. I’m searching here under the rubble for even the remains of lentils and rice, even a little, for my children.

[Amy Goodman] Israel’s energy minister said no basic resources or humanitarian aid, including water, will be allowed into Gaza until Hamas releases hostages. His warning came after Gaza’s only power station ran out of fuel, plunging the territory into darkness. The International Committee of the Red Cross warned in a statement, “as Gaza loses power hospitals lose power, putting newborns and incubators and elderly patients on oxygen at risk. Kidney dialysis stops and X-rays can’t be taken. Without electricity hospitals risk turning into morgues.”

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): And we wanted to show just one more clip. Those two are from the same day, so early on. But I wanted to show one more clip and then get your comment.

[News anchor] [. . .] Extraordinary civilian death toll that has happened as a result of this war. Do you believe that anything that Israel has done in these six weeks of fighting has amounted to a war crime?

[Senator Fetterman] Of course not. Of course not. Let’s not forget what Hamas started. They broke the first ceasefire, and then they attacked Israel and murdered over 1,200 innocent women, children, babies, everything, and brutalized it in the most unspeakable kinds of ways. So that really is the ultimate criminal war. This is absolutely an unequivocal attack to destroy Israel, and we must remember that that’s what started all of this.

[News anchor] But are you comfortable, Senator, with the number of Palestinians who have lost their lives? 7,000 children, 15 or 16,000 civilians dead. Do you believe Israel is doing enough to minimize civilian casualties?

[Senator Fetterman] One death is too many. It’s tragic. I don’t value any Palestinian child life any more than, or any less than, my own child. It’s heartbreaking and it’s awful. But I do fundamentally believe that Israel must destroy Hamas to achieve long changing conditions that allow for peace to prosper.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Norman, can you help us make sense of what we’re seeing in these various clips, and how we might be able to use the media to teach our kids?

Norman Solomon: One aspect is the way in which adjectives are used. For instance, the NBC Report quite properly in the repertorial voice referred to the Hamas attack on civilians as “horrific.” But we’re not getting the same repertoire of voice from that media outlet or other mainstream U.S. outlets to use that kind of adjective to describe what the Israeli military is doing to the civilians in Gaza. So it’s horrific when it’s done to the Israeli civilians, according to the media, and it’s unfortunate and sad when it’s done to the civilians in Gaza.

There’s a similar problem with the use of words like terrorists and terrorism. If we’re going to use words like that, then we can and could justifiably apply it to what Hamas does, then why is it that, to my knowledge, there has never been a big mainstream U.S. media outlet reporting that the Israeli military is engaged in terrorism in Gaza? It’s a complete disconnect because there’s an unwritten rule that is so unconscious in the pervasive atmosphere of U.S. mass media that you would never do that. Can you imagine what would happen to a TV news anchor who matter of factly had just referred to the Hamas attack as terrorism then went on to say that meanwhile the Israeli forces engaged in more terrorism today in Gaza? I mean, leave your keys on the desk and don’t let the door hit you on the way out. That’s what would occur.

And of course journalists understand. Basically, if they want their career they would never dream of doing that. What we heard from Senator Fetterman is very typical, and that is to say, Hamas started it. So that seems to be an open-ended license to kill for the U.S ally Israel. But it’s not logical, because history doesn’t start at point X just because we wanted to start at point X. There’s a history going back months and years before it. You could talk about the Nakba, which started this. Not to find faults is to say that there’s always a context, there’s always a backstory, that as human beings it’s better for us to understand because that’s the way the real world operates.

When I heard the senator speak, it reminded me of something that I quote in the War Made Invisible book from then Defense Secretary Rumsfeld. When he was asked about the civilian deaths that were mounting in Afghanistan after the U.S. launched the so-called War on Terror in late 2001, Rumsfeld said, “Make no mistake about it, every death in Afghanistan, whether it’s Americans or Afghan civilians or anybody else, it’s all the fault of Al Qaeda.” Well, that’s just a complete license to kill. Go around killing anybody you want and it’s all okay because you’re not at fault. Well, that’s a complete absolution for not only past war crimes, but future ones as well.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Yes. Well, I think you’ve given the educators here today so much to think about how to frame these issues and ways to raise this in the classroom.

In the book you note that Biden requested a record $813 billion in military spending in 2023. You write, “This war budget stops up funds that could be devoted to health care, education, housing, job creation, and much more.” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. called military spending a “demonic, destructive suction tube.” How can teachers. teachers’ unions, parents, students, how can we all challenge these priorities?

Norman Solomon: The example you give, I think, is a great teaching moment, if you will, about the distant mirror of when Dr. King spoke in 1967. As I say in the book, he went down to Riverside Church in New York City and he got tremendous media abuse by pointing out what he called that terrible demonic suction tube. Here we are at the end of 2023, and most communities don’t have to walk very far to see that absence of health care, education, housing, and resources.

I think we have this opportunity. Maybe you could say it has something to do with what Paulo Freire talked about that starts with where people are, what they experience, and the deficits in basic social safety nets, social services, public space, and community. How is it that there’s hardly any place to go that isn’t bought and sold, where something is set up to sell you something? Where is our common space and community that nurtures everybody, not to require any money from them? There are so many countless aspects of how our society is suffering, not only as something happening far away, but nearby where all of us of any age are having tremendous impact.

I think another aspect is the culture of violence and the tacit, absurd assumption through omission, through silence, that literally millions of people, mostly men, can be run through boot camps, and can be trained and encouraged to learn how to kill people and use firearms to do it. Then the theory is that somehow, or the pretense is somehow, there’s an off switch, and they come home, and all of them are suddenly discarding all of that training, all of the emotions, all the reflexes and psychological synapses, however you want to describe it. I think the culture of violence is one of those throughlines that we can really talk about, beginning where people are.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Yeah, you’re breaking it all down this evening. I really appreciate this. People may have seen in the chat that we dropped a link to resources for educators to teach more about Israel, Palestine, and war. We hope that you check that out. I also just wanted to point out that Rethinking Schools magazine just had an editorial in our new winter edition inspired by your book. We write, quote, “We need schools to nurture a disgust for war and to expose students to the human consequences of the U.S. war machine. We need young people to come to see themselves as activists for peace and justice, to recognize our common humanity, and to do something about it.” So, I just wanted to recommend that Rethinking Schools also has a resource for educators.

As we move to our next question, I wanted to also point out that Sylvia has an article in the winter issue of Rethinking Schools magazine that describes our country’s long history of activism against militarism in our schools. Peace activists, educators, veterans, labor organizers, social workers, clergy. The Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs, who went to prison for opposing World War I, said, “I would no more teach school children military training than to teach them arson, robbery, or assassination.” So how do we account for the weakness of the movement against militarism in our schools today?

Norman Solomon: Of course schools are part of society. The walls don’t keep out all the different pressures and attitudes. Media is such a powerful educator; usually a miseducator. As you spoke of that memory and information about Eugene Debs, that aspect rarely taught about the history of World War I and the nonviolent, emphatic, articulate resistors, someone earlier in our session mentioned Muhammad Ali, and I think it’s very instructive. I’m old enough to remember the tremendous abuse that he took when he simply took a principled stand, and he said, “You want to send me to prison? Okay, that’s better than me going out and killing people who I have no reason whatsoever to want to harm at all.” I think that’s potentially instructive.

We have many examples, and Daniel Ellsberg is another one. But there are so many. Many whose names we don’t know. People who went to prison during the Vietnam War, not as draft dodgers as the media would put it — there we go with the words again — but draft resistors. And if we can give examples, again, Muhammad Ali is such a great one, somebody who was vilified at the time. Then, with the wisdom of hindsight, we see how heroic their actions were.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Yes, no doubt. Howard Zinn often urged teachers to use Dalton Trumbo’s novel Johnny Got His Gun to teach about the realities of war. So I wanted to ask you if there are other resources that you think teachers should incorporate into their curricula to help them teach against pro-war propaganda, to help them make war visible?

Norman Solomon: It’s such a powerful book, Johnny Got His Gun, and perhaps sometimes teaching or sharing it, he mentioned Dalton Trumbo. He was targeted by the McCarthy era and suffered as a result, as those who challenged institutionalized violence so often do. I think, in tandem with that book, also of Born on the Fourth of July. I was lucky enough to meet Ron Kovic, and his book is such a powerful call for peace, for dealing with realities of war. If students are not familiar with the book, they are more likely familiar with the film, which was perhaps the best star turn that Tom Cruise ever provided to the world. The film Born on the Fourth of July is powerful and would bring home to people of that age or younger what’s involved with going to war and the reality of it.

In terms of other resources, I think in real time it’s so infuriating to read the mainstream press in the United States, to watch the mainstream news, and, as has been alluded to here, I think it’s absolutely correct. The daily coverage by Democracy Now! is just crucial — It is bringing us in real time the human realities of this war machinery as it bears down on exterminating people in Gaza. I’m a big fan of, and have been a bit involved with, the media watch group FAIR, which is online at Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting. The website is just fair.org. For decades now, FAIR has been analyzing news media bias. One of the terrific things is it’s like walking on two legs — FAIR analyzes and organizes activism. So, quite often, when there’s an analysis — whether it’s the New York Times or NPR or anywhere else — they’re very specific. They’re very clear. It’s fact-based. Often it’s empirical. Then they say, “You can send an email to this director of news at this media organization.” So to pressure. Sometimes in a matter of hours they have generated, for instance. hundreds of emails to the New York Times demanding a correction and pointing out the inconsistencies in the flat out lies that are transmitted as actual journalism. I think one of the benefits there is not only that it helps us to get more in the habit, so to speak, of being our own media critics, but also it says we don’t have to just sit back and take it. We can organize effectively, we can talk back to our TV sets, or our scroll, our newspapers, our magazines.

Also, if we wanted to, we could get out the picket signs and picket a media outlet that we think is inappropriate. There are a couple others I want to briefly mention. Commondreams.org, I think, is an excellent source of daily news and commentary. Also, among the many silences that is so atrocious and outrageous in the U.S. media for the last eight years is the slaughter of people in Yemen and the fact that we’ve had three presidents — beginning with Obama through Trump, through now Biden — who have winked a nod and supported the Saudi-led slaughter of people in Yemen. The largest cholera epidemic in modern history was inflicted by that war on Yemen. The UN says close to 400,000 people have been killed in the last eight years, with the U.S. supporting through intelligence and weapons sales to Saudi Arabia that killing. You may remember, a year and a half ago was the fist bump that the President of the United States gave to the de facto leader of Saudi Arabia. Talk about silences and fears documented. You could watch MSNBC for years and barely see any mention of it whatsoever. I would just add that at one level we would say, “Well, gee, why isn’t their coverage? Because the United States is involved,” you would think. In spite of the fact that the U.S. is involved, there’s minimal to no coverage of this killing in Yemen. And yet when you step back and you look at the patterns, it’s even because the United States is involved that the silence has been maintained through the media here.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): It’s astounding that when the U.S. has interests in some region of the world, the abuses that they will turn a blind eye to. My heritage is both Black and Armenian and growing up I always knew that our government didn’t recognize that there was a genocide perpetrated against my Armenian family. It wasn’t recognized for over a hundred years, until just recently it was finally recognized because Turkey was an ally of the United States. So, those atrocities go overlooked. But I really appreciate you sharing those resources with us, and I hope that the educators here this evening will let us know how they’re using those resources. If you use one of the books — Johnny Got His Gun or Born on the Fourth of July — or you start using Democracy Now! or FAIR, if you use some of these resources in your classroom, send us a note at the Zinn Education Project and let us know how you’re using it so we can share that information with other educators across the country.

Norman Solomon: Something I forgot to mention in connection with Yemen, a resource there, which is fantastic, is an organization called the Yemen Relief and Reconstruction Foundation. On their website they’re very clear, they have tremendous information, slide shows, and so forth. The Yemen Relief and Reconstruction Foundation brings us up to speed on what’s really happening in that country and the relationship with the United States.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Wonderful. Yeah, I would love to hear from teachers if they begin teaching about Yemen, how that goes and what they teach. I just have one last question that will wrap up with this wonderful conversation. You write that in the media, “militarism is euphemized, accepted, internalized, and honored with silence, if not praise. Habits of abstraction, buffering and blocking human connection, enable continual war, and scarcely glimpsed consequences for people who are unseen and unacknowledged.” So, how would you respond to teachers who ask how they can teach a curriculum that centers the reality of war, but does not at the same time depress students or destroy their hopes?

Norman Solomon: When I think of that, I pull out from my files a quote from Noam Chomsky, because hope is so crucial, and we can’t really live without hope. For young people, or any people, to feel hopeless is just a nonstarter. This is what Noam Chomsky said, “If you assume that there is no hope, you guarantee that there will be no hope. If you assume there is an instinct for freedom, that there are opportunities to change things, then there is a possibility that you can contribute to making a better world.” In the long run, I think it’s understandable that people will say, “This is too depressing. I can’t wrap my mind around it. It brings me down to try to learn what’s happening in the world paradoxically,” and we can share these experiences. What is the most depressing, the most debilitating, in terms of feeling some hope and optimism to the world is to be passive, and that when we engage, when we connect with the humanity of others, when we work together, when we find ways to be organizing and be proactive about the future instead of consuming dreadful history like it’s Wonderbread on the shelf, it’s enlivening. We’re not going to be told that by the news media. But the fact is, when we’re activists, we’re going to feel much better, quite likely, about the way the world is and can be than if we, on the other hand, just consume the bad news.

Jesse Hagopian (he/him): Thank you so much for lifting my spirits this evening, and I bet a whole lot of other people. I mean, it’s just been an impossible time to see this genocide being perpetrated against the Palestinians in Gaza. It’s so hard to see these images day in and day out, but we do have a way to resist. A nd we had an amazing conversation about how to do that this evening. So, I want to thank you deeply from my heart for helping us in this conversation to learn how to resist better.

Norman Solomon: Well, I really want to say that the Zinn Education Project is really inspiring, and I can’t think of a better organization to be named after, and in tribute to, Howard Zinn. Howard Zinn Presente! He’s here and he’s enlivened by this organizing, and also, Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change. This is how we can elevate our lives. So thanks for all you’re doing to everybody on this call.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

During the workshop, participants watched two news clips about Gaza and Israel aired on October 12, 2023. Hagopian asked Solomon to comment on how the coverage by NBC and Democracy Now! differed. Many teachers said they would use a similar approach in their classrooms.

Resources

See many of the lessons, books, and other resources recommended by the workshop presenters and participants below, beginning with our evolving list of resources to teach about Palestine and Israel.

Lessons

|

Whose “Terrorism”? by Bill Bigelow Subversives: Stories from the Red Scare by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca Greed as a Weapon: Teaching the Other Iraq War by Adam Sanchez |

Books, Articles, and Films

| In addition to War Made Invisible: How America Hides the Human Toll of Its Military Machine, the following readings were referenced.

“Israel’s War on Gaza Is Also a War on History” by Jesse Hagopian “War Made Invisible” editorial by Rethinking Schools editors Teaching About the Wars edited by Jody Sokolower (Rethinking Schools) Johnny Got His Gun by Dalton Trumbo (Citadel Press) Born on the Fourth of July by Ron Kovic (Akashic Books) and adapted film. Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle by Chris Hedges (Bold Type Books) Slaughterhouse-Five: Or the Children’s Crusade, a Duty-Dance with Death by Kurt Vonnegut (Dial Press) The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien (Mariner Books Classics) A Midnight Clear, a film adapted from the novel of the same name by William Wharton. |

News Sources and Digital Collections

|

Costs of War project by Brown University |

Presenters

Norman Solomon is the national director of RootsAction.org and executive director of the Institute for Public Accuracy. He is the author of many books, including War Made Easy. His latest book, War Made Invisible: How America Hides the Human Toll of Its Military Machine, was published in summer 2023 by The New Press.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, and serves on the leadership team of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn