“Everything we experience happens in the flow of time from past to present to future . . . we are swimming in the currents of history.” This watery metaphor runs through Reconsidering Reparations, a book about world history, global justice, and the climate crisis.

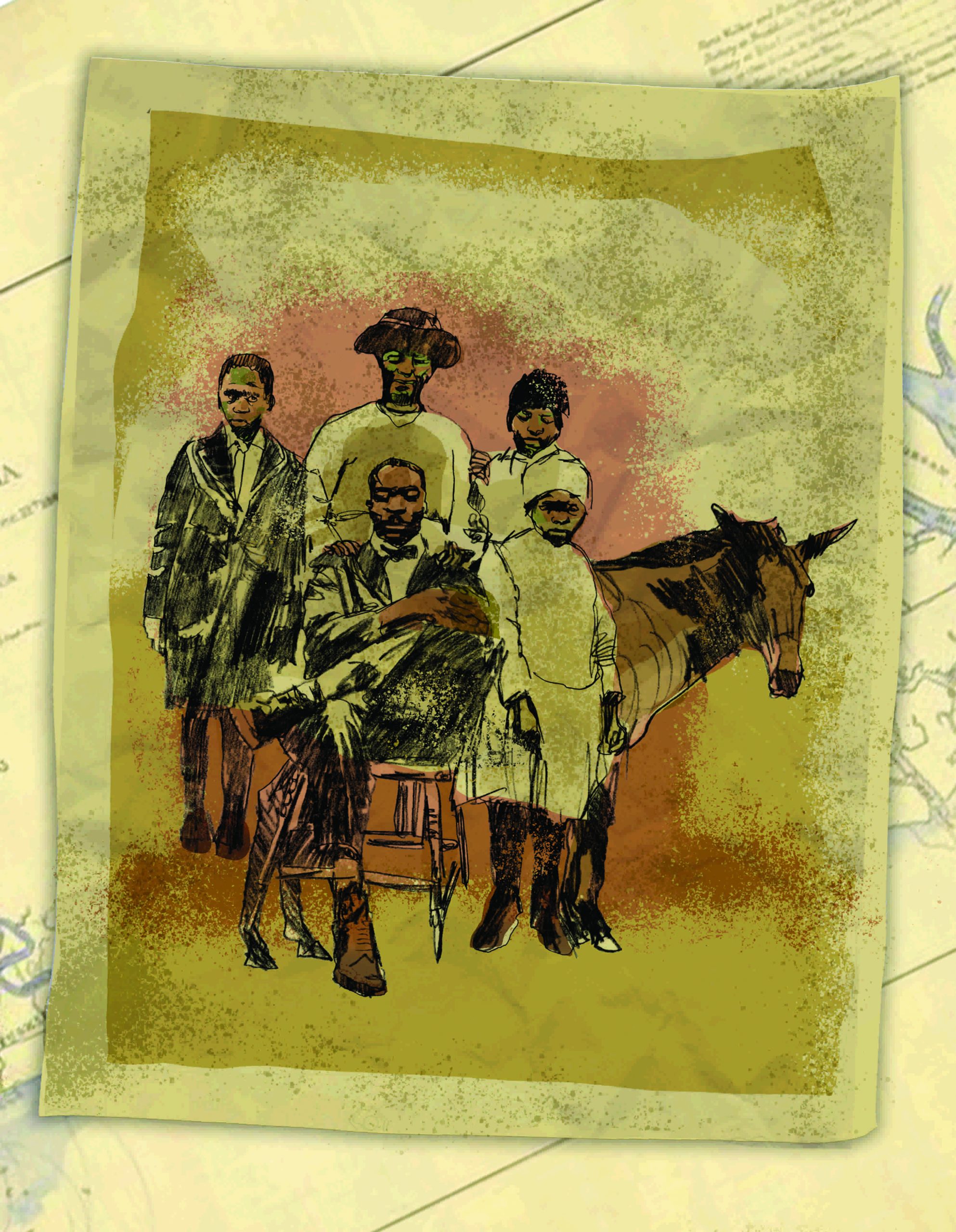

Olúfémi O. Táíwò offers a clear, new case for reparations as a “constructive,” future-oriented project: one that responds to the weight of history’s injustices with just distributions of benefits and burdens. Centuries ago, Táíwò explains, European powers engineered the systems through which advantages and disadvantages still flow. Colonialism and transatlantic slavery forged schemes of injustice on an unprecedented scale — a world order he calls “global racial empire.” The project of justice must meet the same scope.

Olúfémi O. Táíwò offers a clear, new case for reparations as a “constructive,” future-oriented project: one that responds to the weight of history’s injustices with just distributions of benefits and burdens. Centuries ago, Táíwò explains, European powers engineered the systems through which advantages and disadvantages still flow. Colonialism and transatlantic slavery forged schemes of injustice on an unprecedented scale — a world order he calls “global racial empire.” The project of justice must meet the same scope.

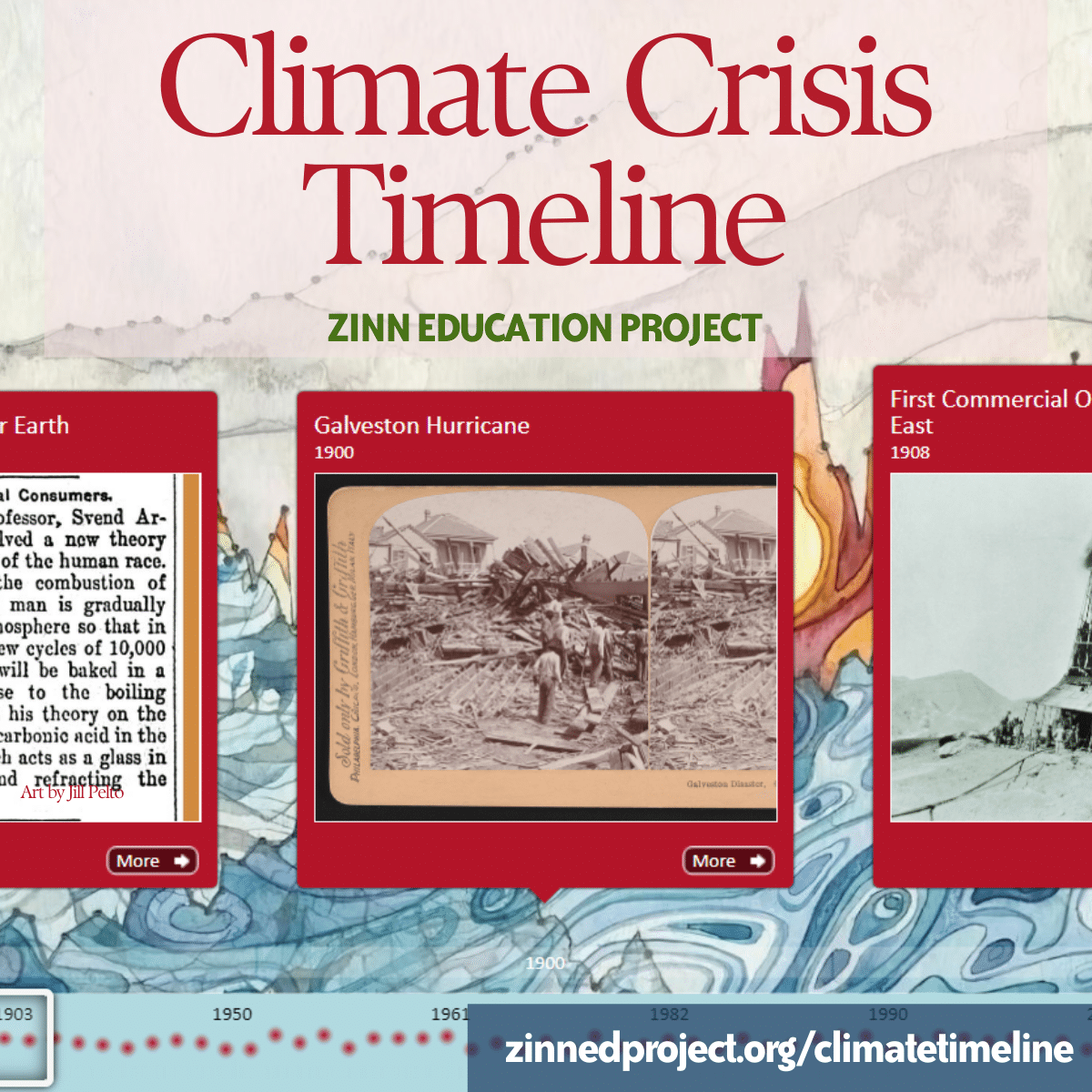

Táíwò describes how the global racial empire took up industrialism and fossil fuel burning that now fuse reparations with preventing runaway climate change. Environmental catastrophes echo past injuries. “If we don’t intervene powerfully,” he writes, climate change “will reverse the gains toward justice that our ancestors fought so bitterly for.” But this calculus discourages despair; it demands global resistance.

Reconsidering Reparations suggests policies, goals, and organizing strategies. And it leaves readers with brilliant advice: Act like an ancestor. Do what we can to shape the world we want our moral descendants to inherit, and have faith that they will continue the long struggle for justice. [Adapted from Rethinking Schools description.]

ISBN: 9780197508893 | Oxford University Press, USA

From Future Perfect: Can reparations be a way to stave off climate catastrophe? by Natasha Lennard in Book Forum

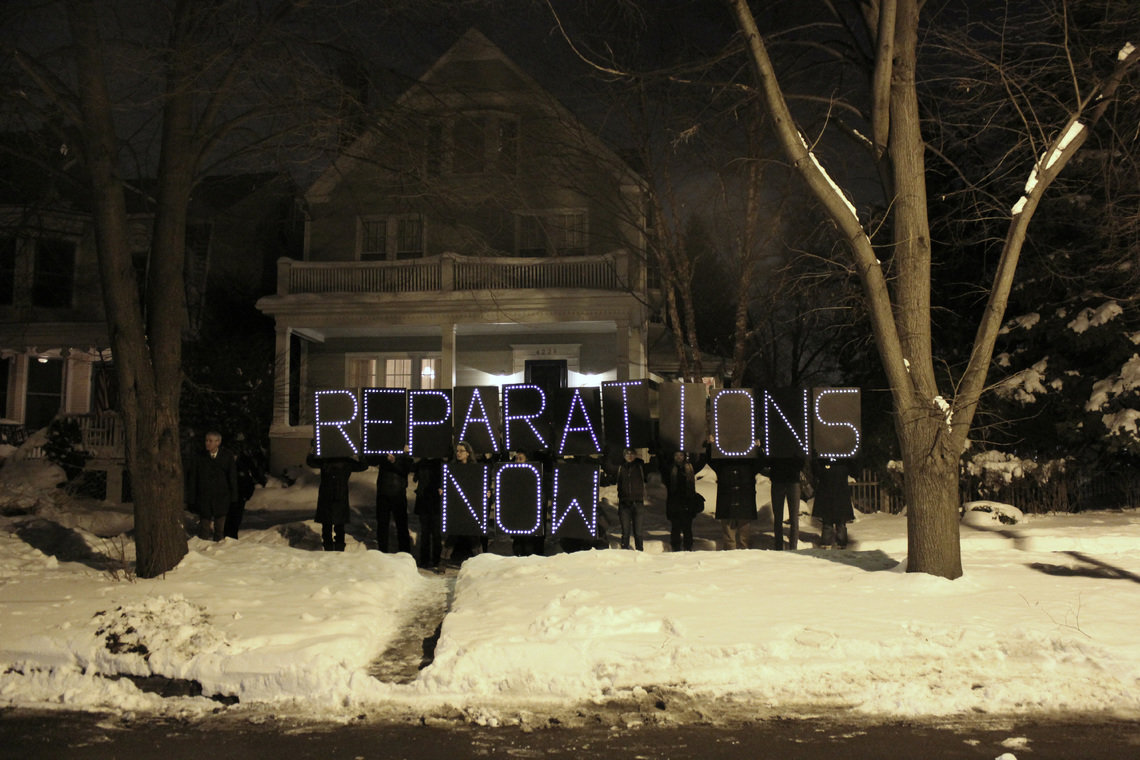

Táíwò works from the premise that a fruitful program of reparations must be future-looking: How can reparations benefit the communities most harmed by histories of colonialism and slavery if those communities remain condemned to suffer and perish in climate catastrophe? The history of capitalist development has meant that climate decimation has been unevenly distributed along colonial lines. Even within the United States, poor Black communities are at the greatest risk from the consequences of climate change. A program of reparations that fails to attend to the climate crisis would also fail to repair the world forged in colonial rule and through slave labor. In response to the question of why those fighting for a sustainable climate for all people need to think in terms of reparations, Táíwò argues that the only way to end climate apartheid is to understand and undo the systems that produced it. . . .

Táíwò avoids . . . problems of historic, individualized responsibility by thinking instead in terms of liability. For him, corporations and powers that have accumulated advantage through global racial empire can be considered liable for bearing the costs of reparations whether or not any of their living representatives can be said to bear responsibility or fault for past harms. “The racially advantaged, the Global North, and institutional repositories of plunder should bear more of the burdens of constructing the just world order, not because of the relationship that they, as responsible moral agents, hold to the injustices of the past,” he notes. Instead, “those advantaged by global racial empire should bear more burdens because of the relationship that their advantages hold to that history.”

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn