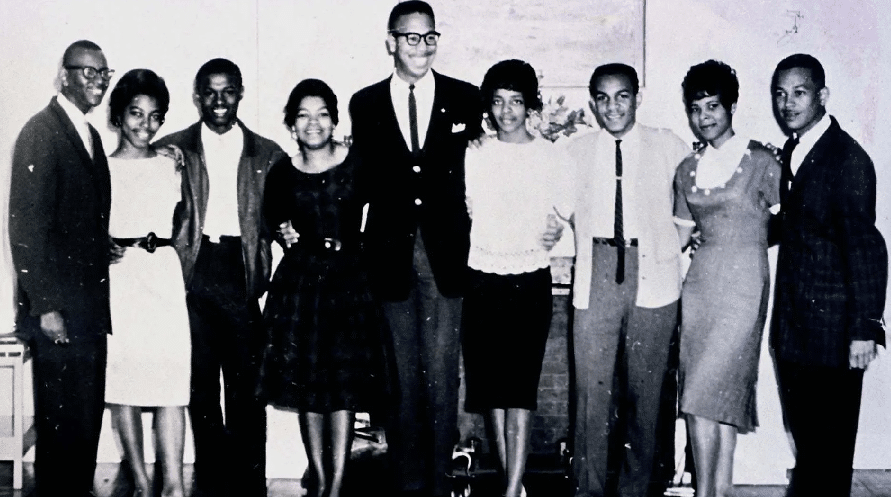

On July 16, 1960, seven Black high school students and a college student entered the Greenville County Public Library. As they quietly read books and magazines, the librarian called the police, who arrived and arrested the students. The eight — Margaree Seawright Crosby, Joan Mattison Daniel, Benjamin Downs, Elaine Means, Dorris Wright, Hattie Smith Wright, Willie Joe Wright, and Jesse Jackson (the college freshman) — were taken to jail and subsequently became known as the Greenville Eight.

On July 16, 1960, seven students from Sterling High along with college freshman, Jesse Jackson, entered the library and were arrested. This group became known as the Greenville Eight. Source: Greenville County Library

This act of civil disobedience was not the first to occur at the Greenville County Public Library. Four month earlier, on March 1, 1960, twenty Black high school students attempted to desegregate the library but were stopped when officials closed the library for the day. According to Joan Mattison Daniel, one of the Greenville Eight, as quoted in George M. Eberhart’s American Libraries article The Greenville Eight:

“Jesse Jackson was responsible for our getting together to stage the sit-in. He had come home in January and needed a book to write a paper. The book was not at the colored branch library, a small, one-room house on East McBee Avenue.” Librarian Jeanette Smith told him it would take another six days to get the book he wanted, which would have been too late. “So Jackson went to the main library to look for it,” Daniel said. “He was told he could not use that library, and that was the beginning of it.” He vowed to come back in the summer.

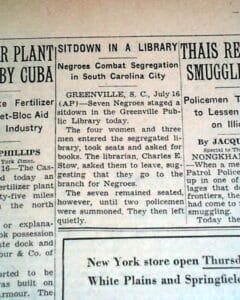

A July 17, 1960 New York Times article about the Greenville Public Library sit-in. Source: Rare Newspapers

The students had been to the library once before in the morning of July 16, but they had left when police arrived and told them to leave or they would be locked up. The Greenville Eight, as they were called (Jackson, Dorris Wright, Hattie Smith Wright, Elaine Means, Willie Joe Wright, Benjamin Downs, Margaree Seawright Crosby, and Daniel) had been counseled by the Rev. James S. Hall Jr., vice president of the South Carolina NAACP. They returned to Hall’s church, but he instructed them to go back, get a book, and sit down, Daniel recalls. “They would probably arrest us but, he said, don’t fear, we would be released.” . . .

Within a few minutes the police arrived and arrested all eight for disorderly conduct. Daniel says they were in jail about 15 minutes before African-American attorney Donald J. Sampson and Hall arrived. The court released each of them on $30 bond. [Continue reading.]

Attempts to desegregate the Greenville Public Library took a more legal approach in the following months, and, after public pressure mounted, the library was reopened as a desegregated facility on September 19, 1960.

The American Libraries article continues:

Although Greenville was not the first library system to integrate in South Carolina (Columbia and Spartanburg had already done so without any controversy), it was the first to do so as a result of public demonstrations by the Black community. The charges against the Greenville Eight were eventually dropped. [Continue reading.]

Additional Resources

“Greenville 8” Together 50 Years After Segregation by John Eby (WYFF4)

Service for All: Integration of Public Libraries in Greenville County (a photographic collection at the Greenville County Library)

The Desegregation of Public Libraries in the Jim Crow South: Civil Rights and Local Activism by Wayne A. Wiegand and Shirley A. Wiegand (LSU Press)

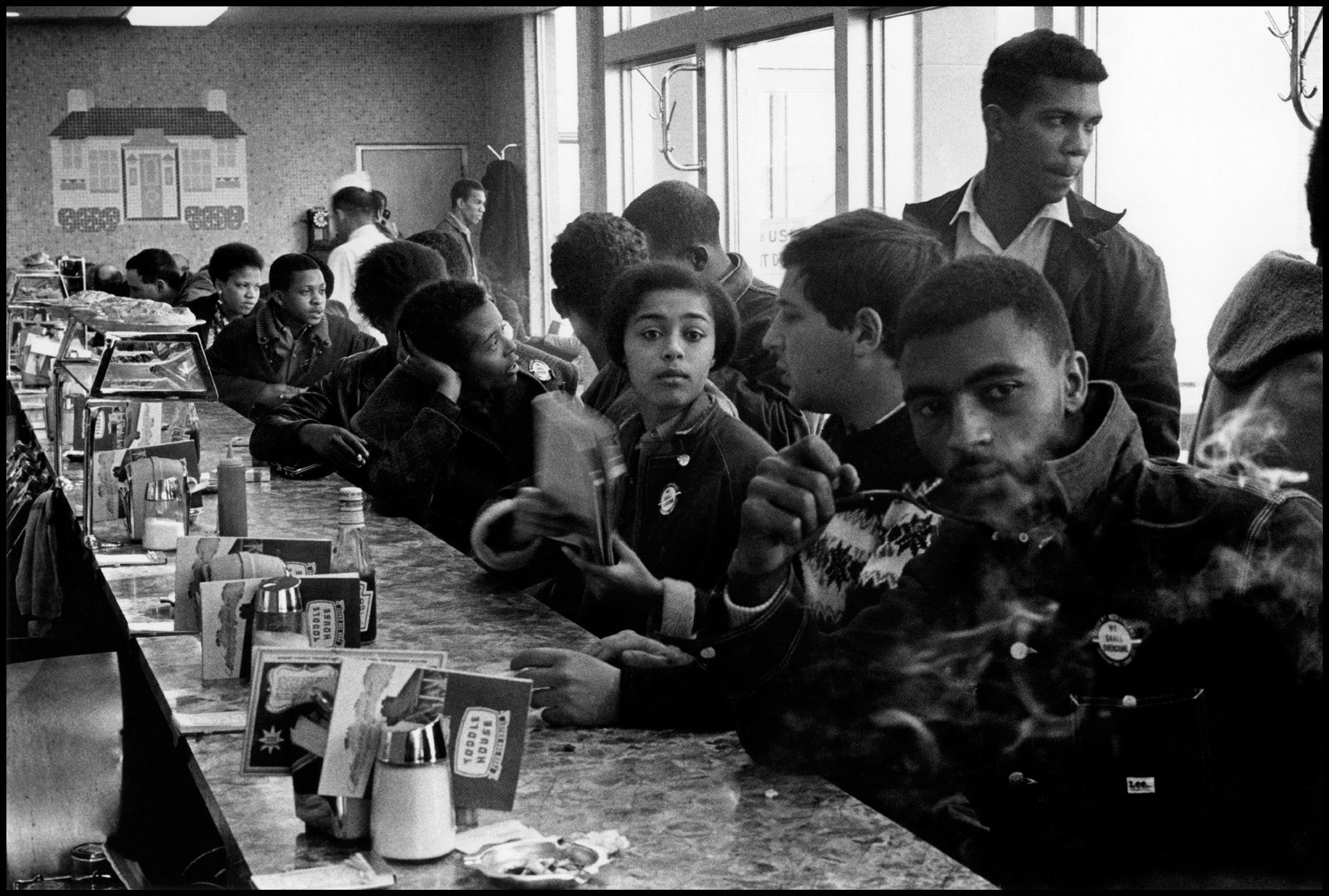

More stories of sit-ins at public libraries.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn