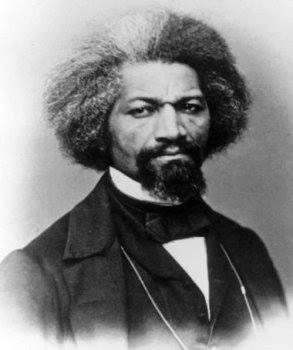

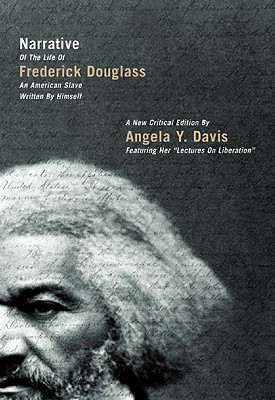

This #tdih post is from the Monthly Review, titled Frederick Douglass on John Brown, 1860.

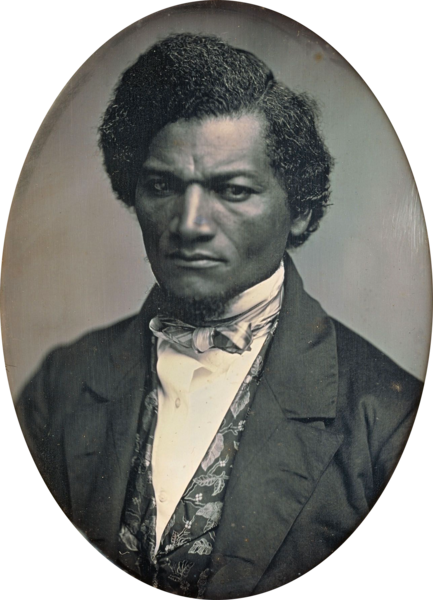

On December 3rd, 1860, Frederick Douglass was set to address an anti-slavery rally at Boston’s Tremont Temple Baptist Church, held to commemorate the death of the radical abolitionist John Brown and to mark the one-year anniversary of his ill-fated raid on the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry Virginia. Boston being Boston, the gathering was attacked by what Frederick Douglass’ Paper described as a “gentlemen’s mob.” The mob was not composed of “practiced ruffians.” Instead, as the paper wrote, its “rank and file, not less than its leaders, claim position with the upper classes of Boston society. They were gentlemen of the ‘DOLLAR STAMP,’ well dressed, well conditioned, well looking, and doubtless, on occasions, pass very well for gentlemen.” Joined by the the city’s mayor and supported by the Boston police, they were determined “to preserve the union of Boston pockets with Southern money” by shutting down any anti-slavery activities.

After a series of intense melees that saw Douglass fighting “like a trained pugilist” to get to the rostrum, only to be torn from the podium by the police and thrown down the stairs of the Tremont Temple, it was decided to move the meeting to the Joy Street Baptist Church, even though its trustees tried to lock their doors on their pastor. If the aim of the attack was to stop Douglass and other abolitionists from speaking, the attacks had the opposite effect, adding fuel and focus to the anti-slavery efforts embodied by Brown. Douglass’ speech that night, reproduced below, was a strident endorsement of what he called the “John Brown way.” Abolition, declared Douglass, would never occur if society appealed to the morality of the slave owner. Slavery would only end if the slave owner feared the violent retribution of the enslaved. “We must make him [the slave owner] feel that there is death in the air about him,” Douglass declared, “that there is death in the pot before him, that there is death all around him.”

Frederick Douglass was often as ambivalent about John Brown as a person as he was about his abolitionist strategy. He did not participate in Brown’s Chatham, Ontario convention to raise money and recruit personnel for the raid on Harper’s Ferry. He refused to join the raid itself. Yet as the slavocracy became more entrenched and militant in their defense of their evil institution, Douglass also understood that radical abolitionism was the only way forward to freedom.

Frederick Douglass’s Speech on John Brown at Joy Street Baptist Church, Boston, December 3, 1860

Mr. President, Ladies and Gentlemen: I occupied considerable attention this morning, and I do not feel called upon to take up much of the time this evening. There are other gentlemen here from whom I desire to hear, and to whom, I doubt not, you wish to listen.

This is a meeting to discuss the best method of abolishing slavery, and each speaker is expected to present what he regards as the best way of prosecuting the anti-slavery movement. From my heart of hearts I endorse the sentiment expressed by Mr. Phillips, of approval of all methods of proceeding against slavery, politics, religion, peace, war, Bible, Constitution, disunion, Union — (laughter) — every possible way known in opposition to slavery is my way. But the moral and social means of opposing slavery have had a greater prominence, during the last twenty-five years, than the way indicated by the celebration of this day — I mean the John Brown way. This is a recent way of opposing slavery; and I think, since it is in consequence of this peculiar mode of advocating the overthrow of slavery that we have had a mob in Boston today, it may be well for me to occupy the few moments I have in advocating John Brown’s way of accomplishing our object. (Applause.)

Sir, we have seen the number of slaves increase from half a million to four millions. We have seen, for the last sixty years, more or less of resistance to slavery in the U.S. As early as the beginning of the U. S. Government, there were abolition societies in the land. There were abolition societies in Virginia, abolition societies in Maryland, abolition societies in South Carolina, abolition societies in Pennsylvania. These societies appealed to the sense of justice, appealed to humanity, in behalf of the slave. They appealed to the magnanimity of the slaveholders and the nation; they appealed to the Christianity of the South and of the nation, in behalf of the slave. Pictures of slavery were presented. The ten thousand enormities daily occurring in the Southern States were held up — men sold on the auction-block — women scourged with a heavy lash — men tied to the stake and deliberately burned, the blood gushing from their nose and eyes, asking rather to be shot than to be murdered by such slow torture. The facts of these charges have been flung before the public by ten thousand eloquent lips, and by more than ten thousand eloquent pens. The humanity, the common human nature of the country has been again and again appealed to.

Four millions have bowed before this nation, and with uplifted hands to Heaven and to you, have asked, in the name of God, and in the name of humanity, to break our chains! To this hour, however, the nation is dumb and indifferent to these cries for deliverance, coming up from the South; and instead of the slaveholders becoming softened, becoming more disposed to listen to the claims of justice and humanity — instead of being more and more disposed to listen to the suggestions of reason, they have become madder and madder, and with every attempt to rescue the bondman from the clutch of his enslaver, his grip has become tighter and tighter, his conscience more and more callous. He has become harder and harder, with every appeal made to his sense of justice, with every appeal made to his humanity, until at length he has come even to confront the world with the pretension that to rob a man of his liberty, to pocket his wages, or to pocket the fruits of his labor without giving him compensation for his work, is not only right according to the law of nature and the laws of the land, but that it is right and just in the sight of the living God. Doctors of Divinity — the Stuarts and the Lords, the Springs, the Blagdens, the Adamses and ten thousand others all over the country — have come out in open defense of the slave system. Not only is this the case, but the very submission of the slave to his chains is held as evidence of his fitness to be a slave; it is regarded as one of the strongest proofs of the divinity of slavery, that the negro tamely submits to his fetters. His very non-resistance — what would be here regarded a Christian virtue — is quoted in proof of his cowardice, and his unwillingness to suffer and to sacrifice for his liberty.

Now what remains? What remains? Sir, it is possible for men to trample on justice and liberty so long as to become entirely oblivious of the principles of justice and liberty. It is possible for men so far to transgress the laws of justice as to cease to have any sense of justice. What is to be done in that case? You meet a man on the sidewalk, in the morning, and you give him the way. He thanks you for it. You meet him again, and you give him the way, and he may thank you for it, but with a little less emphasis than at first. Meet him again and give him the way, and he almost forgets to thank you for it. Meet him again, and give the way, and he comes to think that you are conscious either of your inferiority or of his superiority; and he begins to claim the inside of the walk as his right. This is human nature; this is the nature of the slaveholders. Now, something must be done to make these slaveholders feel the injustice of their course.

We must, as John Brown Jr. — thank God that he lives and is with us to-night! (applause) — we must, as John Brown Jr., has taught us this evening, reach the slaveholder’s conscience through his fear of personal danger. We must make him feel that there is death in the air about him, that there is death in the pot before him, that there is death all around him. We must do this in some way. It can be done. When you have a good horse, a kind and gentle horse, a horse that your wife can drive, you are disposed to keep him — you wouldn’t take any money for that horse. But when you have one that at the first pull of the reins takes the bit in his teeth, kicks up behind, and knocks off the dasher-board, you generally want to get rid of that horse. (Laughter.) The negroes of the South must do this; they must make these slaveholders feel that there is something uncomfortable about slavery — must make them feel that it is not so pleasant, after all, to go to bed with bowie-knives, and revolvers, and pistols, as they must. This can be done, and will be done — (cheers) — yes, I say will be done. Let not, however, these suggestions of mine be construed into the slightest disparagement of the various other efforts, political and moral. [Continue reading.]

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn