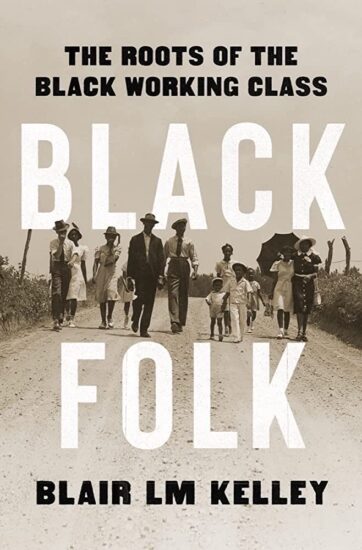

Spanning 200 years — from one of historian Blair L. M. Kelley’s earliest known ancestors, an enslaved blacksmith, to the essential workers of the COVID-19 pandemic — Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class highlights the lives of the laundresses, Pullman porters, domestic maids, and postal workers who established the Black working class as a force in the late 19th- and early 20th-centuries.

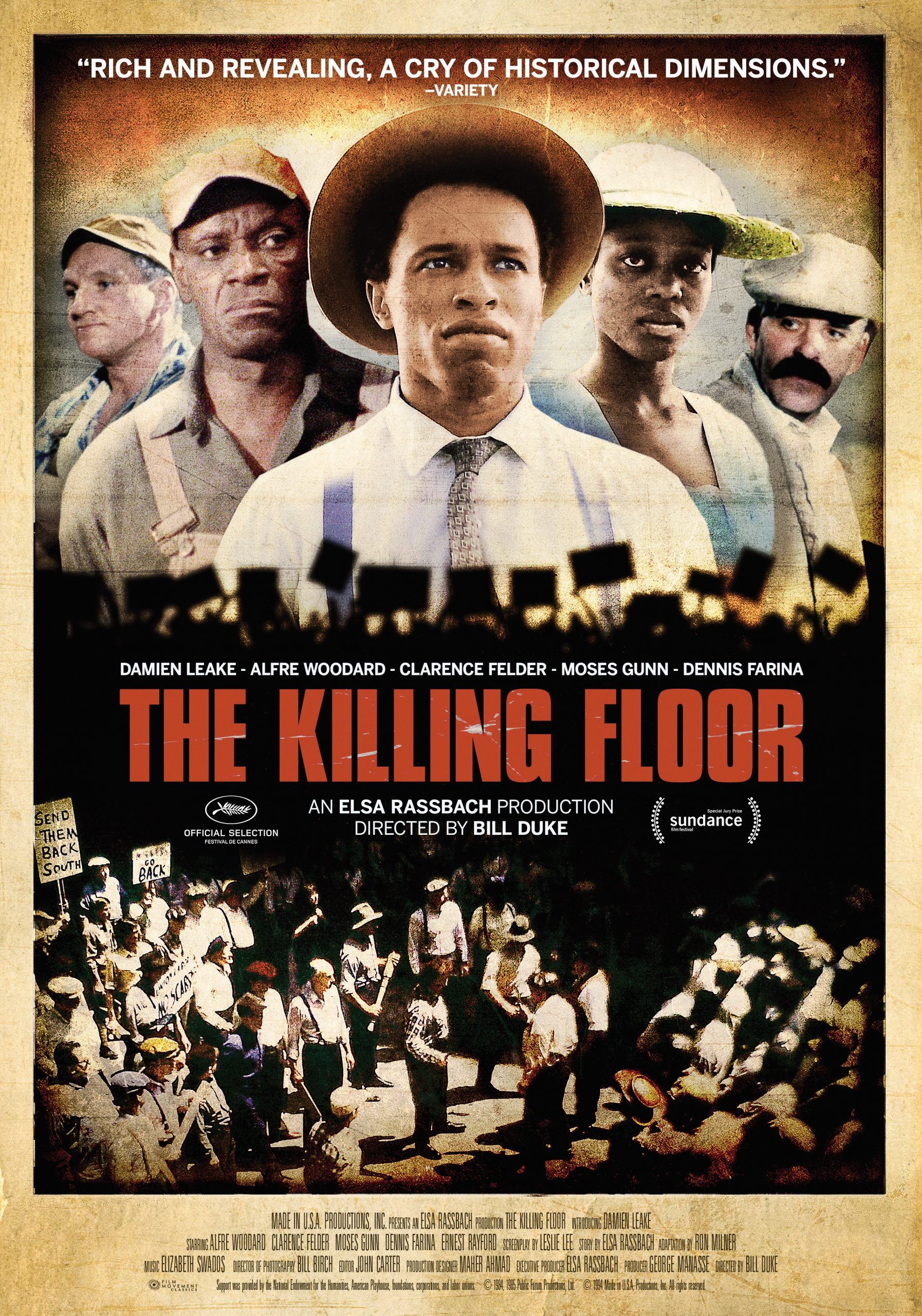

Taking jobs white people didn’t want and confined to segregated neighborhoods, Black workers found community in intimate spaces, from stoops on city streets to the backyards of washerwomen, where multiple generations labored from dawn to dusk, talking and laughing in a space free of white supervision and largely beyond white knowledge. As millions of Black people left the violence of the American South for the promise of a better life in the North and West, these networks of resistance and joy sustained early arrivals and newcomers alike and laid the groundwork for organizing for better jobs, better pay, and equal rights.

Taking jobs white people didn’t want and confined to segregated neighborhoods, Black workers found community in intimate spaces, from stoops on city streets to the backyards of washerwomen, where multiple generations labored from dawn to dusk, talking and laughing in a space free of white supervision and largely beyond white knowledge. As millions of Black people left the violence of the American South for the promise of a better life in the North and West, these networks of resistance and joy sustained early arrivals and newcomers alike and laid the groundwork for organizing for better jobs, better pay, and equal rights.

As her narrative moves from Georgia to Philadelphia, Florida to Chicago, Texas to Oakland, Kelley treats Black workers not just as laborers, or members of a class, or activists, but as people whose daily experiences mattered — to themselves, to their communities, and to a nation that denied that basic fact. Through affecting portraits of her great-grandfather, a sharecropper named Solicitor, and her grandmother, Brunell, who worked for more than a decade as a domestic maid, Kelley captures, in intimate detail, how generation after generation of labor was required to improve, and at times maintain, her family’s status.

Yet her family, like so many others, was always animated by a vision of a better future. The church yards, factory floors, railcars, and postal sorting facilities where Black people worked were sites of possibility, and, as Kelley suggests, Amazon package processing centers, supermarkets, and nursing homes can be the same today. With the resurgence of labor activism in our own time, Black Folk presents a stirring history of our possible future. [Adapted from publisher’s description.]

Excerpts from Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class and Interviews

Today in America, the term “working class” usually conjures images of ruddy white men in hard hats or white waitresses in Midwestern diners, increasingly disgruntled and left behind by the epochal transformations that have reshaped this nation and the world in the last decades. Put simply, the words “working class” are synonymous with the white working class. And in our current political culture, the white working class is synonymous with supporters of Donald Trump — never mind that his base is really the non-college-educated upper middle class. Think pieces seeking to better understand the minds of the fabled Trumpian white working class abound, but the notion that the American working class is white is an assumption that long predates Trump’s time in office.

– – –

From the fight for a $15 minimum wage to unionizing Amazon workers in Bessemer, Alabama, and Long Island, New York, Black people are helping to lead historical calls for change. Even in exploitative conditions, which from the outside appear to leave little space for them to exercise any power, Black workers draw on an unusually strong legacy of collective activism.

– – –

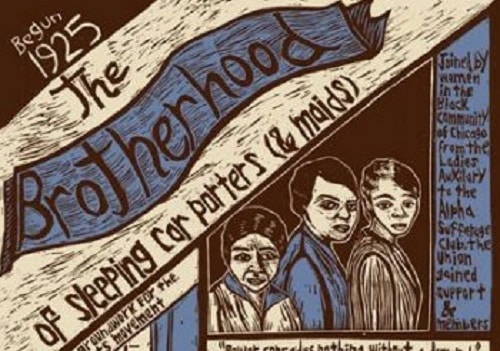

While the Pullman company actively relied on the tropes of enslavement, assuming that Black folk were servile and disempowered, its leaders knew nothing about who the formerly enslaved and their descendants truly were. The porters, and their forebears, had survived the system of chattel slavery by building durable networks of resistance. They knew how to make the most of what they had. They had always made a way out of no way, and as Pullman porters they would continue that resistance work. . . . they ended up building the most powerful Black labor organization in the country’s history.

– – –

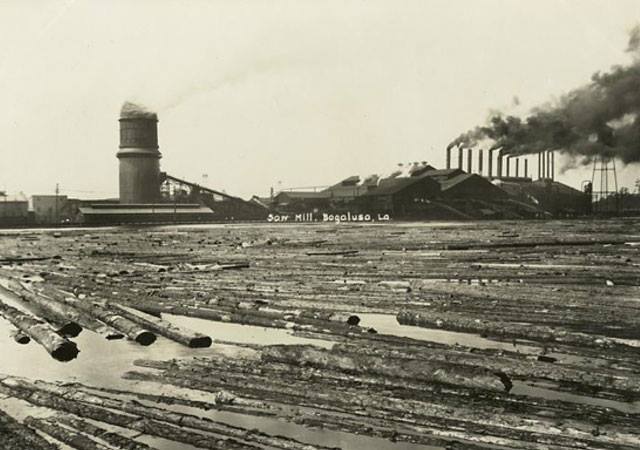

. . . at one time hundreds of thousands of Southern Black women washed the overwhelming majority of clothes in the region by hand. . . . But Black women did well over 90 percent of the laundry. By 1900, had it been considered a single industry, laundry would have been the country’s third-largest employer of Black women, behind agriculture and domestic work.

– – –

This country often speaks of Black resilience, and indeed, Black folks have survived generation after generation of profound oppression and violence. But it is important to remember that not everyone survived. When we plumb the histories of the Black working class, we can recall how we arrived in this moment, and remember the costs borne

– – –

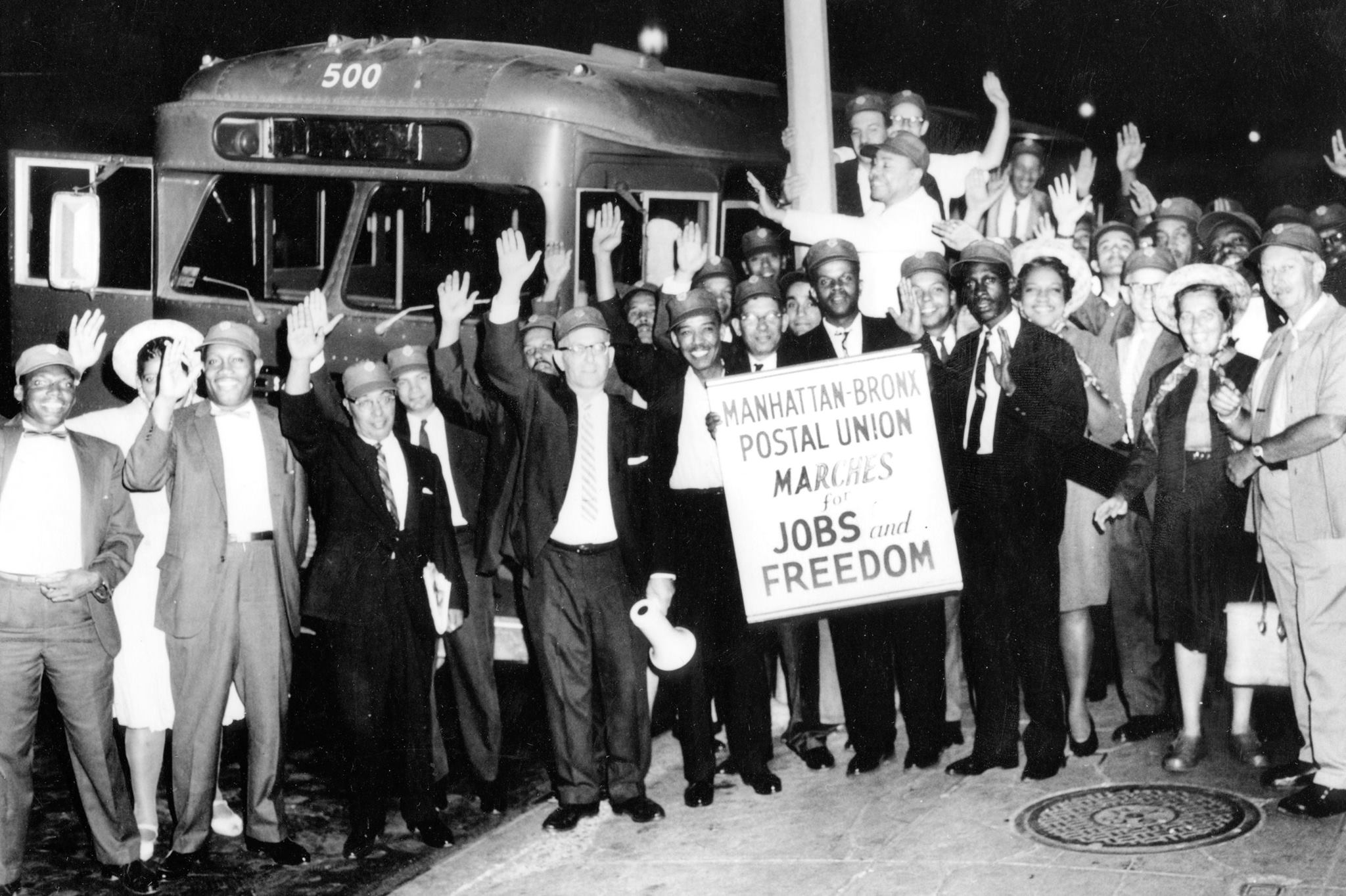

On March 18, 1970, postal workers in New York City began to walk out, forming picket lines outside the Grand Central Station Post office. Their strike was technically illegal; the Lloyd-La Follette Act gave federal employees the right to form unions but expressly forbade them to strike. The unions, and Black union organizers in particular, had made strides over the hundred-plus years that Black workers had been employed by the U.S. Post Office, but by the 1970s the good pay postal workers received had not kept up with inflation. . . . Starting in New York City, where 30 percent of the postal workers were Black, the wildcat strike of 1970 tapped into the experience that came from years of fighting white supremacy in the ranks of the postal service.

Rosie the Riveter is our most powerful icon of this moment in which white women go into workplaces in place of the men who are drafted and abroad and fighting in the war. And we don’t really think of, like, who is watching Rosie the Riveter’s children? Who’s cooking the dinner, getting the groceries together? Black women were not enabled to get many of those industrial jobs, which paid better, but were instead called on to be domestic workers quite informally, right? There’s no national discussion of the fact that Black women will do this work. But as white women work, Black women move into their households to care for their families and children so that we can have the icon of Rosie the Riveter, but we don’t think about the person caring for Rosie the Riveter’s kids while she’s gone. — NPR interview

– – –

I’m a scholar of Black people, and I love Black people. I think we learn so much when we shift our gaze, when we think differently, when we pay attention to other people and glean from their history. Black life has so much to teach all of us about what is possible. — The Atlantic interview

ISBN: 9781631496554 | Liveright Publishing Corporation

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn