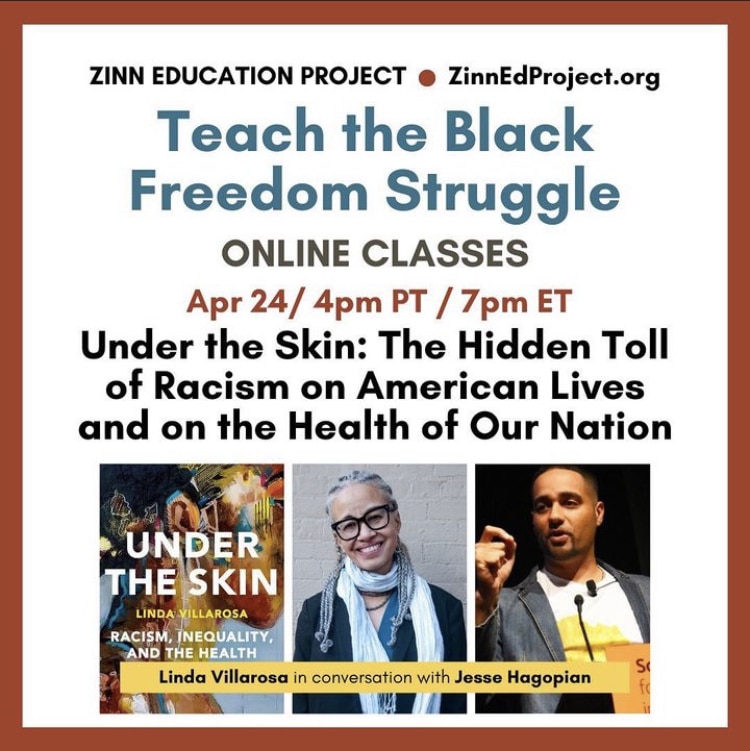

On April 24, 2023, author Linda Villarosa joined Jesse Hagopian to discuss her 2022 Pulitzer Prize finalist, Under the Skin: The Hidden Toll of Racism on American Lives and on the Health of Our Nation, which exposes the persistent racism in the U.S. healthcare system.

On April 24, 2023, author Linda Villarosa joined Jesse Hagopian to discuss her 2022 Pulitzer Prize finalist, Under the Skin: The Hidden Toll of Racism on American Lives and on the Health of Our Nation, which exposes the persistent racism in the U.S. healthcare system.

This session was part of our monthly Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online class series. Don’t miss future sessions — register now.

Participants shared what they learned and additional reflections on the session:

I really loved the stories Linda Villarosa shared with us and her activism. I would like to be able to share these narratives in case studies within my classroom. I would love to start the conversation with the visuals of different people and neighborhoods and how it impacts the person, group, society, and the idea of “weathering” and survival.

The intersection of race and health and the profound level of inequity is far wider and more deeply rooted in racist constructs, institutions, and systems than I ever realized. Attending this Zinn Education Project session was so beneficial to my role as a teacher educator, my work as an educator activist, and my commitment to my own evolution as an informed Black woman.

I learned so much from Linda Villarosa and from the outstanding resources shared in the chat. The history that Villarosa shared about the Relf sisters really stood out to me. I look forward to reading more.

I learned that these decolonized educational spaces are so necessary — not just to bolster traditional classroom experiences, but also to redefine how we learn and grow together. I was moved by the specific stories that Linda Villarosa shared about how Black people are impacted by environmental and medical racism. The way she weaved the narratives together helped me to remember that there are more impactful ways for teaching and learning than textbooks.

Just wonderful to be in community with like-minded people. These sessions help me to know I am not in this work by myself.

Thank you for this series. These classes are so enriching and empowering. I always want to share things I learn with my class. I certainly share with my family. Thank you!!

Event Recording

Recording of the full session, except for the breakout rooms.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: I am extremely happy to welcome Linda Villarosa, the author of the book Under the Skin: The Hidden Toll of Racism on American Lives and on the Health of Our Nation. She is a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine, a professor and journalist in residence at her alma mater, CUNY Newmark J-School, [and also teaches journalism, medicine, and Black Studies] at the City College of New York in Harlem. It is an honor to have you with us this evening, Linda Villarosa, thanks for joining us.

Linda Villarosa: Well, thank you. I am so utterly thrilled to be here as an educator myself, as a person who loved school so much as a kid that I never missed it, and I kept going and getting more education and degrees and things and fellowships. As the parent of two children who I dragged through, but they were very happy, years and years and years of public education and college, and also just have so much respect for your profession and all that you do — right now especially — to teach children and make sure that they understand the truth.

Hagopian: That’s beautiful, especially right now, when teachers are going through so much. We really appreciate that. My mom is in public health, and my wife works in public health, and I just can’t tell you how much your work has meant to me and to our family. It’s really wonderful to get to be in conversation with you this evening. I wanted to start off by asking about your book Under the Skin, because I think it is not only an indispensable guide for understanding health — especially the disparate health outcomes for Black people and Black women — but also for developing a method for understanding how to analyze any social problem. The journey that you take us on in this book, from your individual understanding of social ills to a systemic understanding, I think is really revelatory. You write about how, as health editor in Essence magazine, you firmly believe that, “If we Black Americans know better, we do better.” You write that you approached health through a Booker T. Washington lens of individual self-improvement, imagining “a kind of trickle down effect from health information.” But then you developed a different way to understand why Black people “live sicker and die quicker,” as you put it. I just wanted you to begin by telling us how you developed your understanding of the health systems in this country.

Villarosa: Well, I am a person who has a lot of compassion and empathy for people who learn things slowly, because that’s how I learn things. Essence is a magazine that is firmly grounded in self-help and believing that our mission as editors and writers there was really to help the race, one individual at a time. That also matched my own background from a family of strivers who came from the Great Migration to Chicago. That was part of my own personality.

But as I began to see, my eyes became more open, little by little. One of the times was meeting Dr. Harold Freeman, who taught me that, wait a minute, this is not . . . I thought, “Oh, people who are Black, people who are sick, or those who either don’t know how to take care of themselves or are extremely poor. And those are the only two kinds. And if I work on educating the people who read the magazine, and then we all look out and wrap our arms around the others who were not doing as well financially and economically, then everything would change.” Dr. Freeman took me aside and said, “No, that’s not correct.” Then I started seeing that it wasn’t just the poorest people, Black people in America, who were suffering from poor health outcomes. It was even middle class and upper middle class people. Then I saw my own family member, my father, being treated so badly by the healthcare system that he believed in. As I learned more, I went to public health school, I just got more and more politicized. But honestly, I don’t want to make it seem like I’m some kind of genius. When I was writing the book I realized, “Oh, this is how this works” in my head. But it was only in putting it down that the throughline became really coherent for me.

Hagopian: Yeah, you really do a powerful job of showing how racism impacts Black health, independent of class and other variables. That’s just a vital lesson. I appreciate your vulnerability in that discussion, showing that you didn’t always have it figured out, because I think it helps all of us take that next step in understanding how systems work. You are vulnerable again in chapter three, in a story that you shared about how you didn’t think maternal mortality was a major problem in the U.S. You thought that if it was a problem it was reserved for poor countries or people living in extreme poverty here. And then you deepened the conversation with Katrina Anderson, a lawyer with the Center for Reproductive Rights in New York. Can you tell us about that story and what you discovered?

Villarosa: Well, I play soccer in an intergenerational group on the weekends and Katrina also plays in that group. I had just started working at the New York Times Magazine as a contributing writer, and she said, “Don’t you work for the Times. I want to tell you about what’s going on in maternal mortality in America.” And I was really thinking, can you talk to me later, I just need some exercise in the fresh air in Brooklyn. And she insisted on telling me that we were the only country where the number of birthing people who die or almost die as a result of pregnancy and childbirth is rising. So I was thinking, “That’s hard to believe. But America’s messed up, so okay.” Then she said, “But it’s really Black women who have it the worst.” So I thought, still, “Okay, we always have it the worst.” And she said, “Black women are three to four times more likely to die or almost die related to pregnancy and childbirth. And in New York it’s worse than six to eight times.” I thought, “Well, New York is a really unequal place. I live in Brooklyn, I work in Harlem, I get that.” Then she said, “A Black woman, birthing person, with an advanced degree is more likely to die or almost die than a white woman with an eighth grade education.” And that’s when I stopped and I said, “What? I’m having trouble believing that.” Then I said, “I promise, send me whatever you have on that.”

She was associated with the Black Mamas Matter Alliance, and I got their report, and that’s when I started really digging into that. I had heard that, maybe even 15 years ago, from another study, but it was sort of an isolated study about educated Black parents and infant mortality. But to have this data right there, and to think education doesn’t protect us. Also the disparity is worse at the more educated level. In other words, they were the only difference. If you use education as a proxy for the good things that should keep you healthy during pregnancy and childbirth, including access to health care, then why would the disparity be worse when race was the only factor? That’s when I got really curious and started seeing things very differently.

Hagopian: I’m so glad you did start seeing things differently and got curious. That New York Times piece, I remember when that came out and the huge impact that came with it, and the conversations that were started about structural racism was vital. Thank you for that work. I also wanted to ask you about some of the stuff you write about in Under the Skin where you detail many examples of medical experimentation on Black people without their consent. You write about Henrietta Lacks and the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment that many might be aware of. By the way, I co-edited a book called Teaching for Black Lives and we have a great lesson in that book to help science teachers teach about Henrietta Lacks. Educators should check that assignment out. But the case that you wrote about that I’d never heard of was about Minnie Lee Relf and her younger sister, Mary Alice. This happened to them when they were just 14 and 12. Can you tell us who they were and how their Supreme Court case has changed the country, and also about where they are now? That was a really powerful discussion in your book.

Villarosa: Well, the Relf family, it was two parents and six children who came from rural Alabama to Montgomery. So they were at the tail end of the Great Migration, when people weren’t necessarily going to the north from farms or from rural areas, they were going to cities in the south. And this family came to Montgomery with nothing; the parents had no education and couldn’t read and write. So they were living in a field. There was a Black social worker, Miss Bly, who went and got assigned their case. She really was struck by the two younger girls, who were 12 and 14. And they needed everything, the family needed everything. But these girls really had no education, and she wanted to get them in school, get them in medical care (the younger one was disabled).

So the family went into public housing, they got money from the government to survive, and they got health care through the public health system. But the three daughters got on the radar of the public health system because of their age, and because they were Black. And because, at the time, the officials in the city were seeing so many Black people come into Montgomery and Birmingham and other southern cities, what they were doing was sterilizing young Black girls and teenagers. So the nurses came to the Relf house in 1973, and took the two younger ones and sterilized them. The third one, the older sister Katie, escaped by hiding. She got away and hid and then told their mom and the social worker what happened. So they sterilized the two girls. The social worker, Miss Bly, felt really guilty because she had put the family on the radar, so she went to the Southern Poverty Law Center, it was new then, and Julian Bond was the president of the board, and they got really interested in this case to sue for sterilizing these two young girls without the informed consent of their parents.

So the case became a lightning rod. There were articles about it at the time in the early 70s. The family came to Washington and testified to the Congress, and they won the case. That meant that you cannot sterilize anyone in America without their informed consent, or if they’re minors, without their parents informed consent. But the Relfs, there was a case so they could get money, but they didn’t win that case.

A couple of years ago, I had read about the Relfs, and I decided to find them. I spent a year looking for them. Then, I had given up and I was in Montgomery and by happenstance, I was with a friend helping her teach a class on parenting, just as a favor, and I noticed one of the people had a name card that said Debbie Relf. And I said, “This is crazy. But I’ve been looking for these two women, they should be in their 60s now, Minnie Lee and Mary Alice.” She said, “Oh, that’s my aunties. Do you want their number?” I got their number, I met them, I interviewed them, I put them in my book. The story, that part, got excerpted by the New York Times Magazine — they were on the cover.

Now, this is . . . I haven’t even barely talked about this part. So, I get a phone call. They live in public housing together, and they’re these two elderly ladies, and they’re not doing great. And they don’t quite understand the sacrifice. I mean, they understand their sacrifice, but not what changed in America. So, after the story comes out on, the cover of The New York Times Magazine, I get this email from this woman in Seattle, who is so nice. She’s saying, “I’m a person who benefited from generational wealth. My husband works in the tech industry and I want to do something for the Relf sisters. I want to give them $25,000.” What!? So I said, “Give me your phone number.” You know, in case it was a scam. This is all I asked. I said, “Okay, I believe you. One question: $25,000 each?” “Yes.” I ended up connecting with a nonprofit organization in Montgomery, and they got the money. I saw them last month and they bought a house, so they own their own house. They got out of public housing. They called me the other day and they said they want to get a dog.

Hagopian: That’s great. I did not know that. That’s beautiful. Well done. That really warms my heart to know that follow up, that they got something. Because they are owed a lot more.

Villarosa: And they never got an official apology from anyone yet. But we’re still hoping that someone in the government that sterilized them in our public health service will actually apologize.

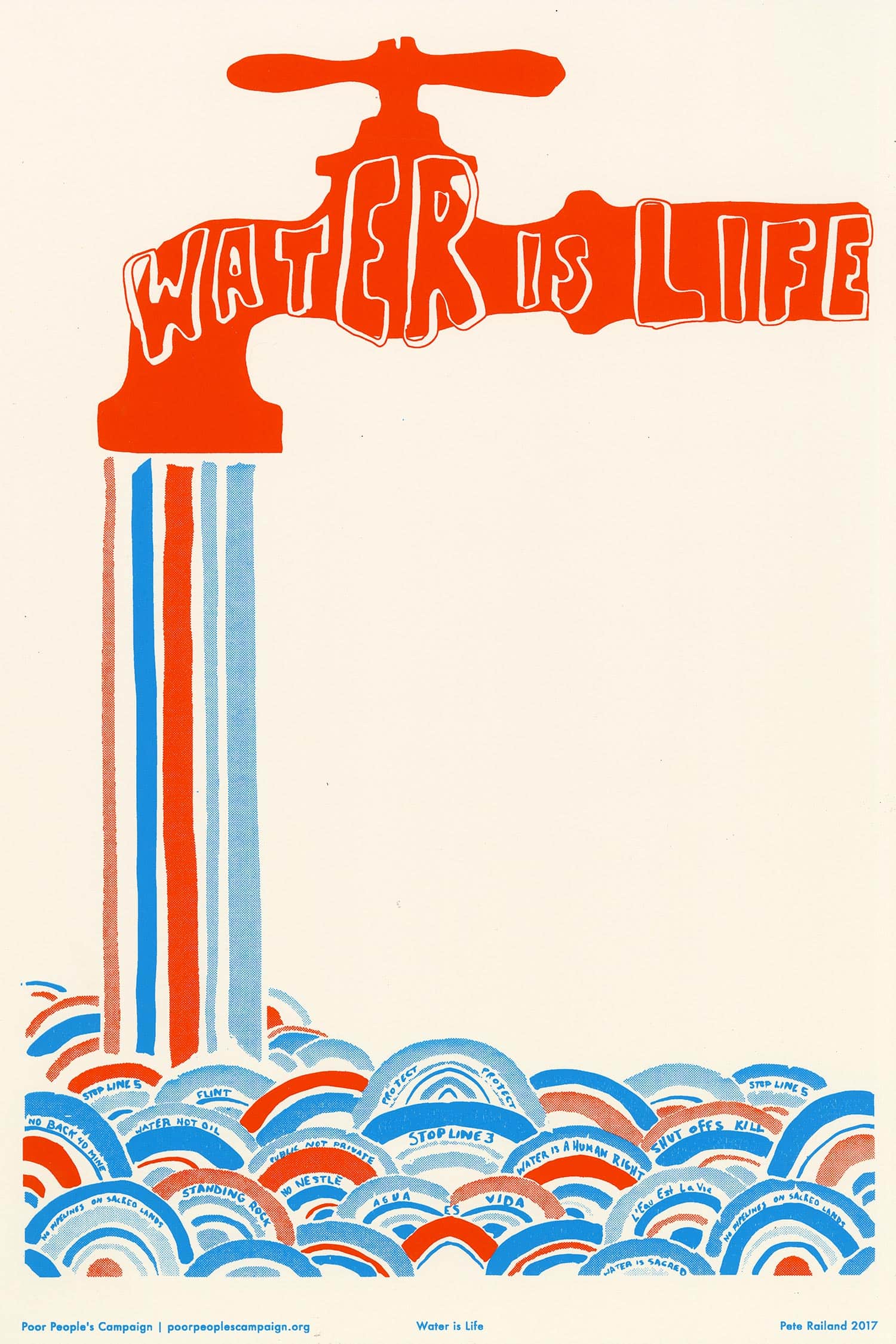

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. Thank you for sharing their story with us all and supporting them that way. I wanted to ask you another question. You titled chapter five of the book Where You Live Matters. And you write, “From foul water in Flint, Michigan, to deadly chemicals that have poisoned a large corridor of Louisiana known as Cancer Alley, Black and poor communities shoulder a disproportionate burden of the nation’s pollution.” So, I was hoping you could speak about this concept of environmental racism and the impact on Black health.

Villarosa: Well, I wrote a story very early on, for Essence, about environmental racism and environmental justice. It was in maybe the late 80s, like 1989. Then I wrote a story for The New York Times Magazine in, I guess, 2019 or 2020. And I was shocked by how little had changed as far as Black people, Black communities and other communities of color, but especially Black communities, being near a polluting facility — whether it’s a refinery, a landfill, a dump, an incinerator. Black Americans are 75% more likely to live in fenceline communities. That means that they’re very close to this polluting facility. That alone: if your air is not clean, if your water — as in Flint, and Jackson, Mississippi — is not clean, then you can’t be healthy. In public health we call it “the social determinants of health” — where you live matters, that’s what the social determinants of health are, whether your community is healthy. I think the misunderstanding about it is that we as Black people are doing something wrong, where when you really look at this, sometimes the community came first, and then the polluting facility came in. As what happened with my first story. In the second story, the refinery was already there, which meant that the community around the refinery was redlined. That meant people couldn’t get mortgages because it wasn’t a very nice or healthy place to live. The city of Philadelphia put public housing as the fenceline community. That meant Black people — and sometimes other people of color, but they’re mostly Black people — lived in public housing. They ended up near this refinery, which was making them ill. Over time, many of them dug themselves out, got out of public housing, but they wanted to live near the community where they were from. So they ended up still in a fenceline community, now in homes that they often owned. Those are two of the things that happen. But too often we’re blamed for doing something wrong, when it’s actually these facilities and industries that are taking advantage of us, or that we end up being located near, and that just has a profound effect on our health.

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. And to compound the problem in our schools, there’s just so little education about environmental racism, climate change, and its impact disproportionately on BIPOC folks. It’s just so outrageous to see the level of crisis that’s facing all of humanity, and especially the most marginalized, and just how little there is in corporate textbooks to help our students understand this. I’m so glad you are bringing that to the forefront in your work. I wanted to ask you another question, because right now in the mess of these attacks on anti-racist education, and all these bills that are being passed across the country to ban educators from being able to teach the truth about racism and Black history, one of the main reasons they say they’ve got to ban all this stuff is because it’s shaming white kids. Then, if we teach classes about racism, it will be very bad for white kids, they’ll be shamed.

I think your book does a really amazing service for everyone to help us understand the way that, as you titled chapter seven, discrimination and ill treatment can harm everybody. In the chapter you write, “Worst off are those at the intersections of race and poverty. And America punishes disadvantaged Black people, but our country judges all the poor, including white people.” So I was hoping you could talk about how racist narratives about health end up being detrimental to the health of all working class and poor white people.

Villarosa: One of the researchers that’s been foundational for me is Arline Geronimus who coined the term “weathering.” She has a new book out too, called Weathering, and it’s really amazing. She’s a professor at the University of Michigan, and weathering is the concept that says, if you are someone who has to fight against discrimination, or fight against ill treatment, in your day to day life — it could be because of poverty, it could be because of racism, it could be because of homophobia, it could be because of whatever — but it’s the long-term effect of having to fight every day just to survive in an injustice society, it weathers your body. And that weathering is a kind of premature aging. It’s the same way that a rock is eroded by water, or a house is battered by a storm. But it also speaks to a kid of resilience to say the house weathered the storm. So I love that dual meaning, it’s very positive. What I asked Dr. Geronimus — because most of her work centers Black people, and she she made her name around infant mortality and how battling back racism hurts Black women’s birthing [and] people’s bodies, and can lead to maternal mortality and infant mortality — so I said to her, “Well, is weathering a Black thing?” And she said, “No, it can be for anyone who’s ill-treated.” She said, “Some of the people who are most ill-treated are the poor white people, because they are the ones who are told, ‘Well, you’re white and you couldn’t even make it.’”

And I thought to myself, while I’m writing this book, where can I go to see what that looks like? So during the pandemic, no one in my family thought I should be doing this, I got in my little Prius and drove to West Virginia from Brooklyn. I ended up, because at the time there was a HIV outbreak because of opioid use that had kind of turned into injecting heroin use, and there was this like bygone times epidemic in West Virginia. So I went to go see what happened there, and I saw people — I mean, it’s a very white state — people being treated so, so badly, and in such dire straits. But I also noticed how old they looked, and everybody I asked, I thought to myself when I’m interviewing people, I thought, I’m going to guess their age. And I would guess, in my head 70, 75, and it’d be like, “I’m 50.” “I’m 48.” So, because of being so ill treated in a . . . They worked in an industry that was not around as much anymore, coal mining, which is difficult. Many of them were hurt. Many of them were addicted to opioids, which were pumped into that state in obscene numbers by pharmaceutical companies. Then it was kind of cleaned up, but they were left addicted without treatment. And they were blamed. I interviewed so many people and all the fears that my family had, it’s like, “Don’t go down there. Are you crazy?” What I saw were people in such dire straits that I just felt like being kind to them, because I felt really bad for them, how they were treated, and how they were blamed for their own situation. And that to me, you know, sort of said, “Oh, weathering does harm everybody.”

Hagopian: Yes. That’s such an important lesson for us to flush out not just in health but in every way. That’s the way that they use racism, hyper attack Black people, but then it drives everybody’s standard of living down. That’s the basis on which I think we can build the kind of solidarity that we would need to change the healthcare system, the education system, the housing systems, that we would all benefit from less oppression — and your book really drives that point home. And you mentioned you were traveling, that time during the pandemic. I wanted to ask you about the pandemic, because it’s been really hard on educators and on our students and on their families. I got COVID in August, and I still have long COVID — I’ve been pretty much continually dizzy from that moment forward. It’s just really taken its toll on a lot of us. We have a lesson by a high school teacher that asked students to consider who is to blame for the COVID related deaths, with racism and capitalism being two of the defendants. In the afterword, you write about the way systemic racism showed up in the ways the medical establishment approached the COVID 19 pandemic. So I was hoping you could say more about that.

Villarosa: I think it was very interesting, because I got asked to do a panel early on in the COVID pandemic, which was, I remember the title was COVID-19 Doesn’t Discriminate. What I did was say, I’m not going to be on the panel unless you change that name, because that’s not true. Any virus — and I grew up as a journalist studying and reporting about HIV/AIDS,, it’s also a virus, so many of the same people were studying viruses and those kinds of diseases. So all of us were like when COVID happens, this is going to discriminate. If these kinds of infectious diseases do discriminate against, people who are the most marginalized, so the ones that weren’t on Zoom at work, but actually out working in communities that didn’t get testing right away, or definitely didn’t get the vaccine right away. Also, who were harmed by the healthcare system already. That means that they may not believe in the healthcare system, are afraid of it, have been hurt by it, and then don’t want to get tested or vaccinated because of fear. And fear, that makes sense because of hurt that has happened to them. So right away many of us, when it was “Oh yeah, COVID doesn’t discriminate.” It was, “Yes, it does.”

And people under the radar, even I remember, it was like 2020, in March, when I started thinking about this and writing about it early on, there were underground conversations of Black people in public health and other people of color that were saying, “This is going to be a huge problem for Black people.” And it ended up being that way.

The other problem was the intersection of environmental racism. So, in places that were already polluted, this was a problem of the lungs — if your lungs were damaged because you live near an incinerator, you live near a refinery, the air isn’t good in your community, then you’re going to have worse COVID hospitalization and higher death rates. And that happened right away in Cancer Alley. I know that one of you here said you were from New Orleans, and, you know, I thought about that, because I remember the study came out in April 2020 and it made the intentional link about people who live in communities where the air is bad have worse COVID outcomes. Then I just thought, oh, no, this is, again, Black people who are so much more likely to live in communities where the air isn’t clean.

Hagopian: That’s a really important link you make there. I just wish that was part of the mainstream discourse. Instead, each problem is siloed as separate, as if we could solve one without addressing the other. You just synthesize them so beautifully in your writing, and you write really powerfully about the problem of systemic racism and healthcare is not new, and how it dates back to the period of enslavement. So I thought I’d ask you one more question before we allow teachers to break and meet each other and discuss a little bit more before we come back. I just wanted to ask you about how health care was treated for enslaved people and what the impact of these vicious medical experiments that were being done during the period of enslavement as well.

Villarosa: I think it’s a complicated issue, because in some ways we had, as enslaved people, we had really good health care — we were taken care of, in some ways, because our bodies were worth money. It was like, ‘Oh, we have to keep these people alive, we have to make sure that they’re well enough to work for free, we have to make sure that they have children, because that gives us more free labor.’ The second thing is we had our own health care that African enslaved people brought over from the motherland, and we had our own kinds of medicine to keep each other healthy. There were midwives; Black midwives were taking care of everyone, including the white people, and they were some of the best medical practitioners at the time.

Alternatively, what happened was myths about us, a Black enslaved people, were going around in order to justify enslavement. One of them was the idea that we had these inferior bodies so that we had worse lung function, which makes no sense now. But it was a myth that was pushed forward by scientists, by doctors at medical schools, in medical journals, the idea that we have poor lung function and working in the fields actually strengthens our lungs. Even worse and more sinister is the idea that we have really high pain tolerance. I remember, I was part of the 1619 Project, and when the book came out, they brought in a professor from Harvard to work with me, and what she said, I had looked into this false idea, pushed by medical people at the time, mostly southern doctors, many of whom were slave owners, that we have this superhuman pain tolerance. And I was calling it a myth. And what she said was, “Be careful, don’t just call it a myth. It is more than a myth. It was something that is patently false but that was forced into the conversation, forced into medical books, and actually forced into history by people who were considered experts. So that’s different from just this false notion, it was actually something that was theorized as being true.” My eyes were very much opened by that work I did on the 1619 Project, and thinking about how those myths that were leftover from 400 years ago still remain in medical training and practice to this day. That was, to me, the most heartbreaking part of it.

Hagopian: Yeah, I want to pick back up on that after the break and talk more about how these were more than myths, these deliberately false narratives were used to construct race.

So, we have time for just a few more questions now. I’m excited to keep the conversation going, so I will begin with a couple of mine, and we’ll see if any come up in the chat that we have time to get to as well.

It looks like people had some fruitful conversations, though. Looks like they appreciated that conversation of weathering, and that’s definitely a term that I want to start incorporating into my own vocabulary, and my own class and classrooms as well. But, Linda, I wanted to ask you about the conversation that you have in your book, that’s just a fascinating study, really, in the social construction of race. I think you cite studies about how people believe all kinds of wild ideas about biological differences between white and Black people — including that Black people don’t feel as much pain, as you touched on. That’s something that I really found interesting because I also organized with professional athletes, and there’s been some important studies that came out about how Black NFL players are put back into the game a lot sooner than white players after they get injured because these myths that started during slavery are continuing to exist. So, if you can tell us about some of the many misconceptions about biological differences between people of the so-called races and what the implications are for how Black people are treated in the medical system.

Villarosa: Well, I think the one that is really the most harmful is the idea that we have the sort of superhuman tolerance against pain. Then, when we go into the medical system, we are undermedicated for pain. It really showed up for me, the way it showed up worse was during COVID, in 2021, there was this physician named Dr. Susan Moore, a Black woman physician in Indiana. She went into the hospital for COVID, she was really ill, and she was in pain. She’s a doctor, so first of all she talked about what the protocol was for treatment and she was shut down. Then she asked for some pain medication because something was really, really hurting in her shoulder, I think her neck and shoulder, and she was treated as though she were drug seeking. I think eventually she might have gotten the pain medication, but not at the beginning. Then she ended up leaving that hospital, she died, she ended up dying of this. And when the hospital investigated, looked into her because she made a Facebook live video — she had a picture of herself in bed in the hospital, tubes in her nose, telling this story. She said throughout, “This is how Black people get killed.” That’s how I found out about her.

Then they did an investigation of this and they found out that some of the hospital staff was intimidated by her medical knowledge. So that is saying so many things. One, that we shouldn’t be listened to, and we’re shut down when we express our legitimate concerns. We as human beings will know more about our bodies than anyone else and we should be. But if you’re a physician, you also know more about your own body plus you know about the treatment and protocol. But also the idea that it seems like a throughline from that old 400 years ago — Black people can endure huge amounts of pain in order to justify this system of slavery that is keeping our country afloat, is making people rich. And the throughline to today is that there are studies where medical students and residents were asked about some of these myths and forty percent believed at least one of the myths — and the myths included that Black people have thicker skin than white people. Do Black people have higher pain tolerance, do Black people’s blood coagulate differently. These are all not real, but forty percent of not doctors, but the next generation, believed at least one of these myths, which means that there’s a throughline right to today’s medical practice and training.

Hagopian: it really was staggering to hear that. It’s not just the general public that have these myths, it’s the people who are charged with providing health care that also hold these myths, and that they’re reproduced in medical schools. That inaccurate information is even being taught, just that was eye-opening for me.

Villarosa: I was speaking at a Columbia School of Nursing a couple months ago and there was an assistant professor who stood up and she talked about the medical textbook. We’re not talking about around-the-way university, this is Columbia Nursing School, and she piled up her textbook, and she showed that she was crossing out the things that were outdated in the book. I was in shock and it was some of these myths. One of them is, I think, around kidney function, that Black people and white people have different kidney functions. It’s based on the false idea that Black people have more muscle mass as a group. Obviously, you can’t see my little tiny skinny arm, but I do not have a lot of muscle mass. The idea that Black people have more muscle mass, thus, we should have a different kidney function reading. And there’s a race correction. I just had one, I had my kidney test, and I saw the race correction. It was like, “This is your reading, if you’re Black this is your reading. If you’re white . . .” and plus it’s just Black and white. It leapt out to a whole lot of other people, and the Black was circled for me. I just thought this is so ridiculous, that this sort of race correction that’s based on something false from the past still exists in modern medicine.

Hagopian: Yeah, well, I think you just touched on Matt’s question in the chat. He said “Growing up, I was told that Black people had longer, stronger and better muscles than white people. That’s a myth, too, right?”

Villarosa: Well, certainly some Black people have long, strong muscles. The problems come when you assume that the whole group of whatever you’re talking about all has this thing. So clearly Black people do not as a group have lower lung function, which is leftover from enslavement. There’s a race correction on the spirometer, which is a medical device that measures lung function, and I remember thinking, I grew up in Denver, Colorado, so that’s the Mile High City, I ran track, I’m like, ‘I have great lung function. I’m the Serena Williams of lung function.’ But I still want to ask my doctor when I had a spirometer reading several years ago. I wonder if she flipped the switch and did the race correction. So, that means it doesn’t take into account individual people, it’s just looking at you as a member of a race, and that is bad medicine.

Hagopian: No doubt. There’s another question that came in here about “how does the myth/theory that Black people are not as knowledgeable or intelligent as white people, how did that get started? What does that have to do with our conversation?”

Villarosa: Well, I think it’s the same thing: you’re trying to —during enslavement, which lasted centuries — you’re trying to say that this group of people deserves to not have full rights. They deserve to be tortured — to be treated badly, to work from sunup to sundown with no payment, their children can be taken away from them, their spouses or their loved ones can be separated from them, we can whip them and beat them and lynch them — under the idea that something’s different about them, including their intelligence, they don’t have the same feelings of love and of caring. So, all of these are myths that support this, capitalism, supporting slavery, which was really bolstering up our country and making many, many people in the south and all over the country very wealthy.

Hagopian: Wherever there’s money to be made off of it, you’ll see them propagate these master narratives that benefit white supremacy. For sure. There’s a question that came in about “how do we challenge this inequitable health system that is infected with structural racism through and through?” Throughout the book, I think, you write about grassroots activists and doulas and Black medical students and patients who have organized to fight against systemic racism in the healthcare system. I really appreciated that you didn’t leave it with all the attacks and the oppression but also showed the resistance that’s going on at every level. I was inspired by your stories of activism in the Black Mamas Matter Alliance and the Birthmark Doula Collective. Then a story near the end touched me because I’m in Seattle and I was glad to hear you tell the story of Naomi [Tweyo] Nkinsi.

Villarosa: So she challenged the kidney function question. What I love is, and that is going to change for sure, is in the process of changing, some of it has already been stricken from some medical textbooks. That is something that we won’t be seeing soon. But I’m going to say two months ago I was at a medical school and after I gave a lecture two young Black medical students came up to me and said that they walked out of their classroom. They had walked out recently because the professor was teaching the kidney, the EGFR it’s called — the idea that Black people should have a race correction because we have more muscle mass, and thus our kidney function is different. They got angry and they pushed back against the professor, which is scary when you’re in medical school and medical school is hard. You’re the lowest rung; the professor has everything. The professor just said, “Well, it’s in the medical textbook.” And so what they said was, “Okay, you’ve got two people, one is a skinny dude named Barack Obama, who’s Black, and one is a bigger guy who’s really muscular, and his name is Arnold Schwarzenegger. So how could, you know, that doesn’t make sense?” And then the professor got mad, pointed to the textbook, they walked out, it created this kind of change and conversation at the school. I thought it was funny because I was with them at the school all day, and I noticed that everywhere I went they went — you’re going to lunch, we’ll go with you. I realized that was really scary for them, and they just wanted to be near me because I was just like, “I’m so glad you did that.” I just wrapped my arms around them, figuratively, to support them, and I think that’s what we have to do.

Because I do see students, especially — I’m a college professor, so I see these very activist students — trying to change, trying to make a difference, pushing back against us as professors and administrators. Often, it really makes me happy when high school students will send me a note that says, like, “I was charged with interviewing someone, and I want to interview you. So I want . . .” And I always say yes, always, always to any high school student who wants to understand more, I always say yes. I’m impressed with and think that we really have to support young people, I mean, not necessarily young, but anyone who is trying to change the system and make a difference and push back against ideas and structures that no longer make sense.

Hagopian: No doubt. What a rich conversation we’ve had. If you look at the chat, people are just dropping so many great resources to help teach this and shouting out their groups that they had wonderful conversations. So, thanks for sharing all about what you spoke about in your breakout groups and for asking questions, and giving us all more resources to teach this better in our classrooms. I had just one more question, and I think it dovetails with another question that was in the chat. Then, if there’s any other last questions, drop it in now. But I think we’ll begin to wrap up with a last question or two here. Somebody asked about the difference in treatment of the crack epidemic and the opioid epidemic? I think it was Sarah who said that “it really gets me heated. Do you ever see there being a reckoning?” That just made me think not just that, but also what’s the impact of mass incarceration on Black health, as well?

Villarosa: I think what happened with people who were addicted to crack was they were treated like criminals. There was such a lack of sympathy, empathy, compassion, care, for people who were addicted to this drug that was poured into communities, especially Black communities, and they were incarcerated and given extreme sentences. That was just unfair. Then when you saw the flip side, when — I discussed this in the book — to talk about when showing the difference, even in journalism, of here’s what crack looks like, and it’s this dark, scary, dangerous people who need to be controlled, and then on the opposite side, when the opioid crisis happened and it was mostly white people, the stories were, it’s someone who got addicted to pain medication after they got injured as an athlete or something like that. Which is valid, but it was just unfair, the way the coverage went, and the way people were treated. It just was racialized, in a way that was really extremely unfair. I think you asked something else, but I always am bad with a two part question.

Hagopian: Just following from that, the impact on mass incarceration on Black health.

Villarosa: Well, I think when you lose a family member to incarceration, that’s unfair, that’s long, longer than it should be. Families break up, but it affects communities. So, if you’re in communities that are also suffering from sanctioned desegregation and discrimination, then you lose people from the community, you lose family members, you lose loved ones, you lose people who could bring in money. Everything affects our health. Everything that happens in your community affects your health, and any community that’s devastated — whether it’s from mass incarceration, whether it’s from environmental injustice, or whether it’s from segregation that is historical — you end up making people sicker. Period, because where you live matters.

Hagopian: Yes. Wow, what a rich conversation. I can’t thank you enough for giving us so many more perspectives and examples of how to build healthier communities and oppose the structural racism in health care. It has been really fun getting a chance to talk with you this evening. Thank you so much.

Villarosa: This is so great. I really have enjoyed this.

Hagopian: Good.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Audiogram

In this audiogram, Linda Villarosa discusses often overlooked effects of racism in public health.

Resources

Many of the lessons, books, articles, films, and other resources recommended by the presenters and participants.

Lessons

|

Water and Environmental Racism by Matt Reed and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca How to Make Amends: A Lesson on Reparations by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca, Alex Stegner, Chris Buehler, Angela DiPasquale, and Tom McKenna The Red Dot of Environmental Racism by Alma Anderson McDonald Repair: Students Design a Reparations Bill by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca Teaching Sacrifice Zones by Rosemarie Frascella What We Don’t Learn About the Black Panther Party — but Should by Adam Sanchez and Jesse Hagopian Who’s to Blame? A People’s Tribunal on the Coronavirus Pandemic by Caneisha Mills |

Books and Articles

Films

|

Aftershock by Paula Eiselt and Tonya Lewis Lee Takeover: How We Occupied a Hospital and Changed Public Health Care by Emma Francis-Snyder |

This Day In History

The dates below come from our This Day in History collection, which contains hundreds of entries all searchable by date, state, theme, and keyword(s).

|

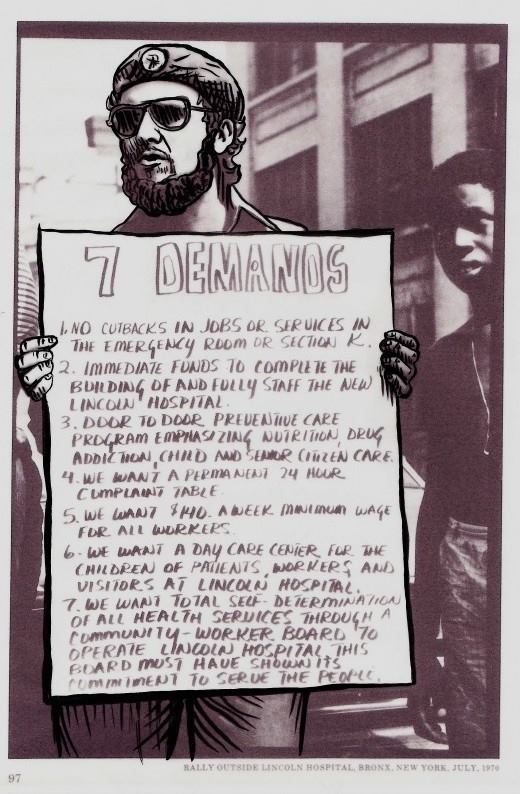

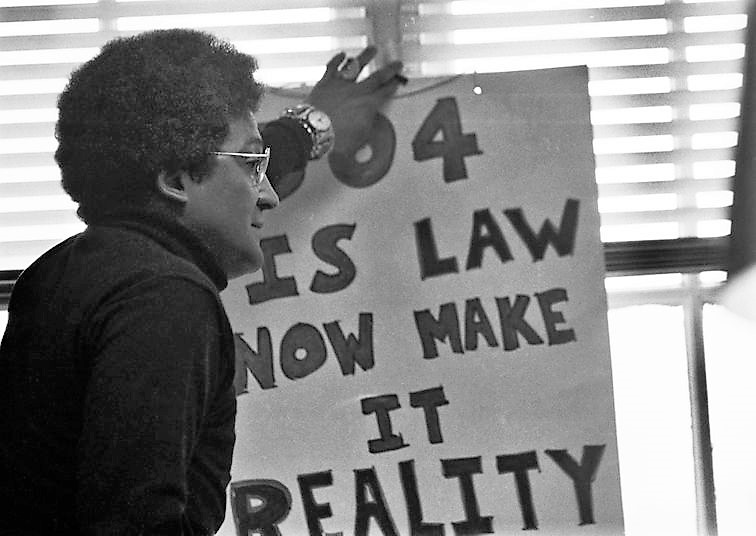

April 23, 1866: Freedmen Demand Equal Medical Treatment Oct. 7, 1873: Henry E. Hayne Accepted at USC Medical School July 1, 1970: The Lincoln Pediatric Collective Forms to Serve Bronx Community July 14, 1970: Young Lords Occupy Lincoln Hospital April 28, 1977: Disability Rights Sit-Ins Force Enactment of Section 504 June 5, 1981: AIDS Epidemic Recognized by Medical Community June 11, 2002: African American Residents in Louisiana Win Their Fight Against Shell Oil March 11, 2020: World Health Organization Declares a Pandemic |

Participant Reflections

With more than 170 attendees, polls showed participants were 30% K–12 teachers, 20% teacher educators, 7% family members of a student, and 5% historians. Here are more comments that participants shared in their end-of-session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

An important reminder that myths are more than they appear on the surface. When they are patently false but presented as truths in textbooks, they have detrimental impacts on those being misrepresented. We have to challenge and demystify the false narratives that continue to perpetuate harm to the most vulnerable.

The overall connection between race and health care. It will be great to deliver this to my high school students. Also, the idea that people need to speak up and not allow being “weathered” to run us all down.

Racism wears on the body like water wearing away rocks. Demographically, a white person with an 8th grade education has better outcomes than a BIPOC person with an advanced degree.

The patently false narratives that persist because of the medical–industrial complex.

The power of environmental racism on the health of so many communities.

I learned how racism proliferates in our communities in ways that most people don’t recognize. Ingrained and systematic racism is so harmful, yet many don’t believe that it exists.

The connection to the way Black folx are being treated today and its link to the period of enslavement. The historical and generational experience continually impacts the lives of Black folx as a result of structural racism.

There was a lot, but the idea that medical misinformation is still so prevalent today — everyone at every level needs to be better informed in order to keep pushing back on untruths.

The concept of “weathering” that Arline Geronimus dedicated her career to exposing needs to fundamentally alter the way that we speak about implicit biases, poverty, etc. Linda Villarosa’s emphasis on the ubiquity of weathering across racial groups should be a way to unify disparate groups of Americans, particularly in this time in dropping life expectancy.

What will you do with what you learned?

I will bring this back to my educator groups to discuss how can we incorporate this in our curriculum.

My students are in the middle of a quarter long civil rights unit spanning from Reconstruction through the modern day. And while I stress the connections between multiple movements long arcs, this is a helpful reminder to continue to connect to the present day impact of historic thinking and deliberate actions and misinformation.

I teach the history of race and racism in medicine to medical students and will think about 1) how to share lessons with K–12 educators and 2) how to couple critical and intersectional frames of inquiry with research about organizations and people who are doing health justice work to show the multiple ways of thinking about weathering.

I teach electrical engineering labs in the school of engineering, I do have a difficult conversation lab where I talk about racism and prejudice and I plan on bringing this up there so my predominantly white students can get some exposure to the lies that we are fed.

I’m a retired public librarian. I will suggest to my former library that they offer/create a public program on these topics.

Use the information in literature discussions for texts on Henrietta Lacks as well as texts that reference drug addiction during previous eras and connect the dots comparing to today.

I am going to add this to my Tuskegee lesson to bring in what happens to women and the unfairness in the medical field.

Will be sharing with my workgroups and committees in my district in order to improve professional learning for teachers and learning for teachers.

I will add this to my human rights course and also my American history civil rights unit.

I have already started to share stories from this book with my students. At this point, we have talked about Dr. Cartwright and the medical experiments of Dr. Simms but I plan to incorporate even more of the information into my classes.

Work on an environmental justice curriculum.

I will continue to teach physical therapy and medical students about the race-based fallacies persisting in their curriculum. And, collaborate on ways to eliminate them.

I will share the information and teaching materials with classroom teachers and support staff, and work to get others to start engaging with these programs and engaging with this important curriculum.

I will help organize a Teach Truth event that invites people to connect oppressions and strategies for liberation.

Presenters

Linda Villarosa is a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine, former executive editor of Essence Magazine, and former editor for the New York Times. Villarosa is a professor and journalist in residence at CUNY Newmark J-School, and also teaches journalism, medicine, and Black Studies at the City College of New York in Harlem. She is the author or co-author of three books, including Under the Skin: The Hidden Toll of Racism on American Lives and on the Health of Our Nation.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, and on the staff of the Zinn Education Project.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn