The Flint sit-down strike, which started on Dec. 30, 1936, represented a shift in union organizing strategies from craft unionism (organizing white male skilled workers) to industrial unionism (organizing all the workers in an industry). The sit-down strike changed the balance of power between employers and workers.

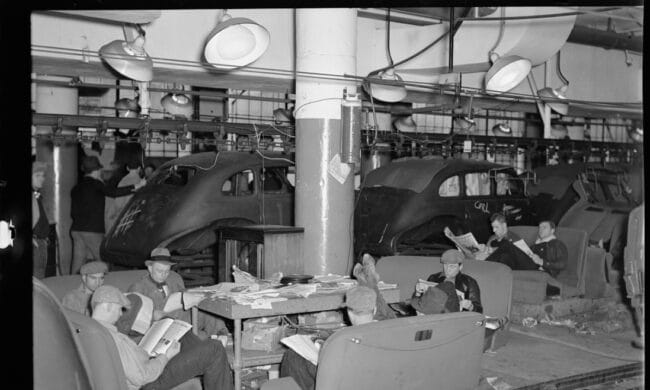

Sit-down strikers in the Fisher body plant factory number three in Flint, Michigan, circa 1937. Photographed by Sheldon Dick. Source: Library of Congress

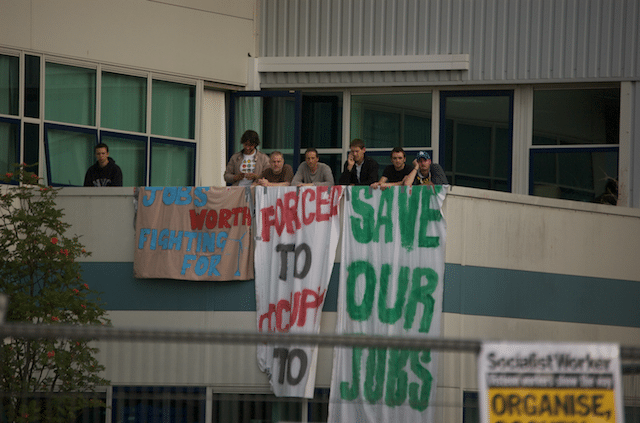

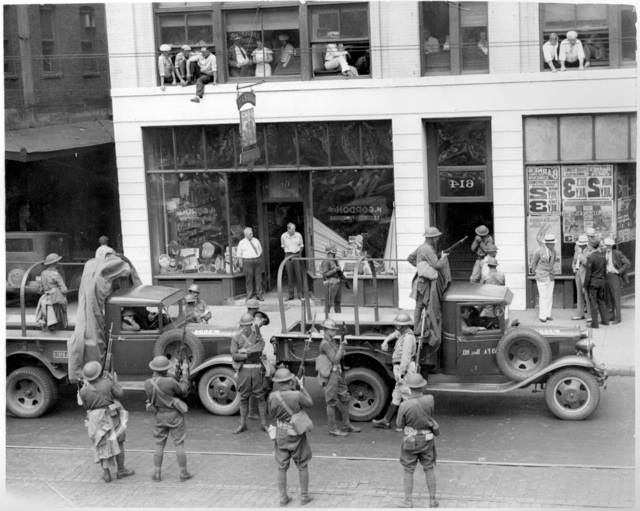

When workers go on strike, they set up picket lines at workplace entrances impeding production and keeping strikebreakers out. The police have traditionally sided with the owners. Picketing workers were vulnerable to attack by the police, who were frequently reinforced by company thugs. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, it happened over and over again. The strikebreakers went in and the strike was lost.

In a sit-down strike, the workers occupy the workplace. This makes the employer’s equipment and machinery vulnerable in the chaos of a police attack. The sit-down strike changed the balance of power by assuring workers ability to stop production. The United Auto Workers (UAW) argued that General Motors (GM) were the lawbreakers, not the workers. GM’s failure to bargain in good faith placed them in serious violation of the National Labor Relations Act.

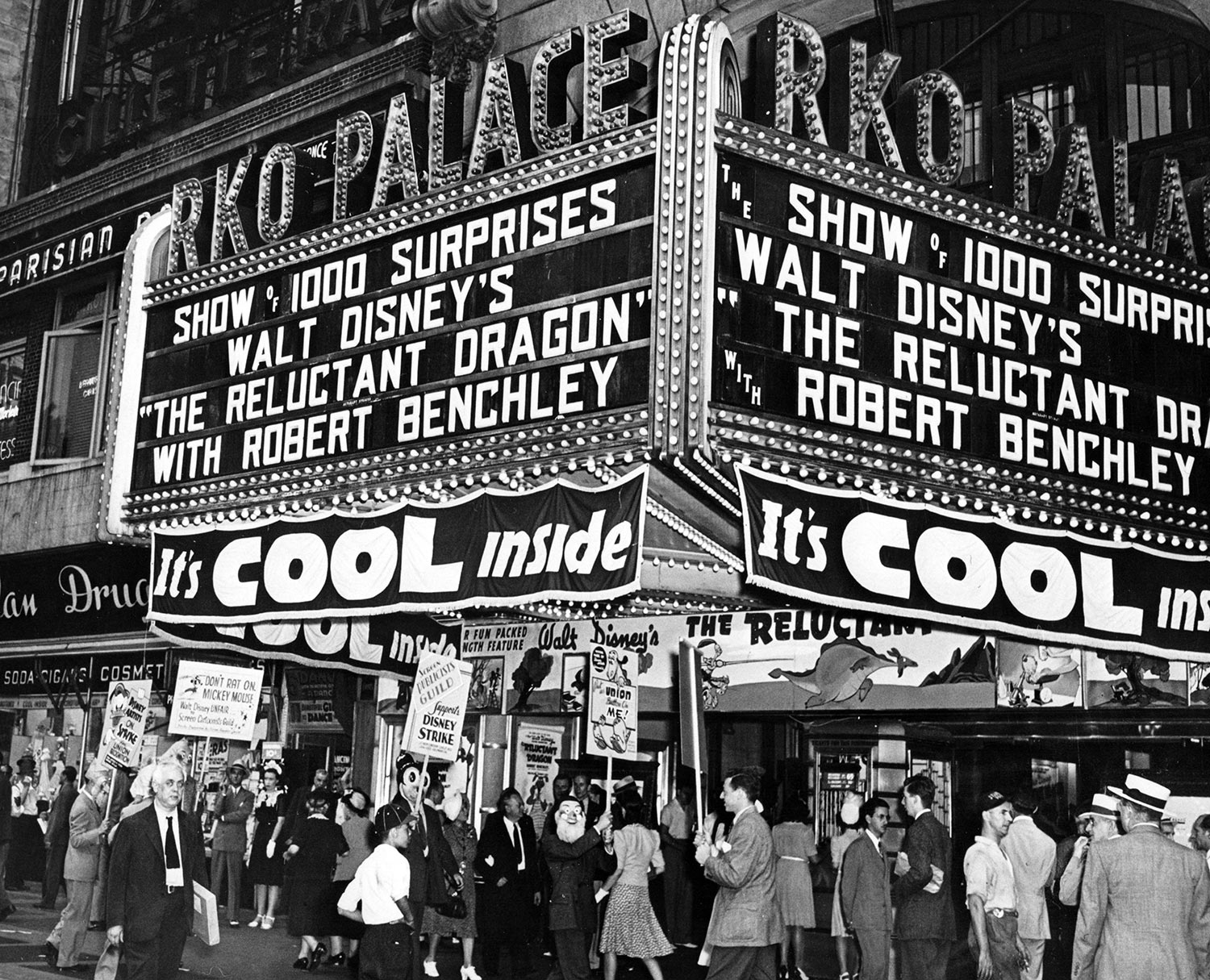

The sit-down captured the front pages of newspapers across the country and around the world. A new union pitted the United Auto Workers against the world’s largest industrial corporation, GM. At a time when the official unemployment rate was twenty five percent, sympathy for unions was very high. The UAW victory inspired hundreds of sit-downs across the country, with over a hundred in Detroit alone. Industrial unionism took off, with everyone from the Woolworth girls to steelworkers wanting to join the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO), later the Congress of Industrial Organizations, led by United Mine Workers President, John L. Lewis.

The sit-down story was filled with larger-than-life characters on both sides. Lewis was an imposing man whose voice rolled across the room like thunder. He even had unforgettable eyebrows. On the GM side was the brilliant engineer from MIT, Alfred P. Sloan. Unfortunately for GM, Sloan’s arrogance and sense of entitlement managed to anger even President Roosevelt and his wife Eleanor.

The secret of the union’s success was dedicated worker organizers in the workplace and communities. Bob Travis was the UAW’s man on the ground in Flint, meeting with workers in their homes, churches, and bars. Genora Dollinger organized the Women’s Emergency Brigade, which fought key battles with the police and helped protect the strikers. Henry Clark, an African American foundry worker, organized 4,000 fellow workers at the Buick foundry, much to GM’s amazement. Support for the strike ran deep in the community with donations and countless volunteers.

In April, Chrysler workers organized and won their demands in a sit-down strike. The numbers tell of the UAW’s success: membership rose from 30,000 in October of 1936 to 400,000 in October of 1937.

As Herbert G. Gutman and Stephen Brier point out in their book Who Built America? Working People and the Nation’s Economy, Politics, Culture, and Society:

The UAW established a general union, Local 156, that organized workers in all of Flint’s industries. CIO forces working within the Democratic Party also quickly won control of the city government, ousting local politicians who had ruled with corporate support for decades.

A new labor movement was on its way, changing the whole country.

This entry is by William Bryce, a retired Labor Educator (Wayne State University Labor School), video producer (Public Television), trainer (multiple union clients), and lead organizer with the AFL-CIO. He has lived in Detroit since 1971.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn