On Jan. 9, 1873, Delaware’s Convention of Colored People gathered in Dover to discuss and demand state provisions to educate their children. They adopted a resolution condemning schooling discrimination in Delaware and asserting their rights as citizens and taxpayers to the benefits long provided to white residents. An excerpt from that resolution, courtesy of the Colored Conventions Project, reads,

Proceedings of the Convention of Colored People Held in Dover, Jan. 9, 1873. Source: Colored Conventions Project

From our population of over twenty thousand souls, or nearly one-fifth the entire population of the State, the Legislature does not provide a solitary school, nor appropriate a single dollar of State money. We hold this discrimination as against the genius of government; insulting to the laws of Congress; detrimental to the best interests of the State, and outrageous to the colored tax payers.

We say against the spirit of the age, because non-progressive in its character and in the interests of ignorance; because tending to perpetuate poverty, multiply crime, and aid in human degradation . . . .

This discrimination is outrageous to the colored people, because it is sullen opposition against their rights as citizens. It is founded upon no principle, backed by no argument, but sustained entirely by a prejudice founded upon a long course of false education.

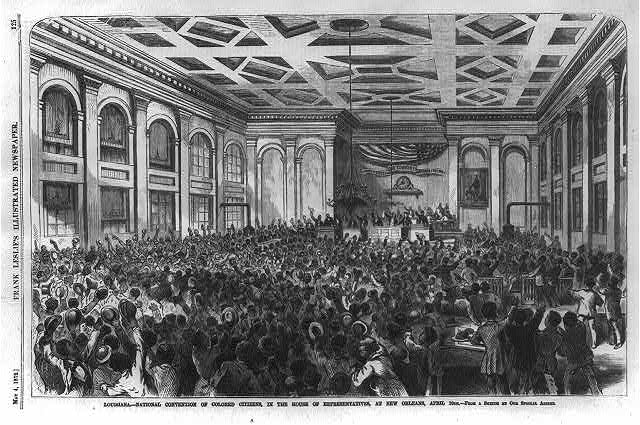

From the 1830s until after the Civil War, Black delegates met in both national and local conventions to discuss important and timely topics like education, labor, and human rights. According to Delaware Public Media, the first Convention was held in Philadelphia in 1830, and the last was held in Macon, Georgia, in 1888. At the Convention held in Dover in January 1873, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper addressed the Convention and spoke of the need for Black people to continue struggle for equal rights.

According to Dr. Gabrielle Foreman, as quoted in Delaware Public Media, the Colored Conventions were,

. . . a hidden movement that hasn’t reached the kind of predominance, the kind of stature, that the Abolitionist Movement and the anti-slavery and the Underground Railroad movement has.

One of the reasons we might argue that that is the case, is because there’s an interracial partnership both in the Abolitionist Movement and in the underground railroad. Which sometimes gets represented as white allies and supporters who, through noblesse oblige and the largesse of their generosity, helped victims. But the Colored Conventions Project really highlights Black agency, Black leadership, Black organizational power.

Learn more in the Zinn Education Project national report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction,” and find teaching resources on Reconstruction below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn