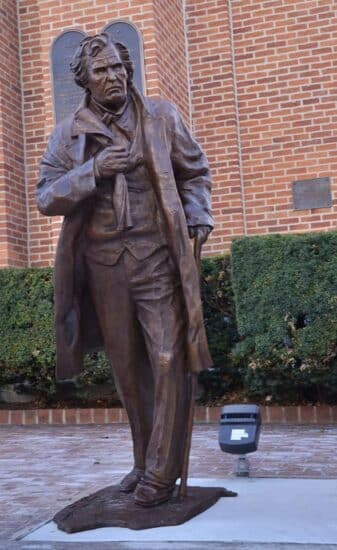

Statue of Thaddeus Stevens, dedicated on April 2, 2022 in Gettysburg. Photo by Gettysburg Licensed Town Guides

Wicked . . . wretched . . . evil . . . hard . . . malignant . . . vindictive . . . domineering . . . revengeful . . . unforgiving . . . implacable . . . cunning . . . mad . . .

Thaddeus Stevens has been called all these names, and more. He can lay claim to being one of the best-hated men in our past.

Milton Meltzer wrote this in the foreword to his 1967 book for young people on Reconstruction era legislator Thaddeus Stevens.

We are pleased that thousands of visitors each year to Gettysburg will now be encouraged to learn about Stevens with the placement of a statue by the Thaddeus Stevens Society in front of the Adams County Court House. The sculptor was Tennessee artist Alex Paul Loza, who describes his process in “The Making of a Monument to Thaddeus Stevens” on WUTC’s Scenic Roots.

Gettysburg Mayor Rita C. Frealing and sculptor Alex Paul Loza with the statue of Thaddeus Stevens on April 2, 2022 in Gettysburg. Photo by Gettysburg Licensed Town Guides

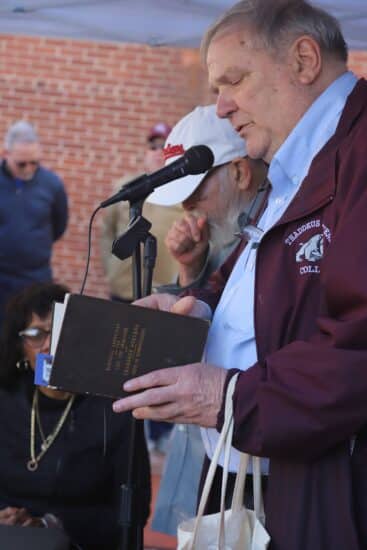

The statue was dedicated on Saturday, April 2. Teach Reconstruction campaign advisor and supporter Michael Charney, who also was a major donor for the statue, spoke at the event. Below are two recordings (from different angles) of Charney’s speech, a recording of the full event, and a transcription of Charney’s remarks.

Recording Version One of Michael Charney’s Speech

Recording Version Two of Michael Charney’s Speech

Michael Charney. Photo by Larry Miller.

A few years ago, the 150th anniversary of the 14th Amendment was coming up.

Given the 14th Amendment’s commitment to equal protection of the law, given the 14th Amendment’s commitment to birthright citizenship, given the 14th Amendment’s section that says no insurrectionist should serve in the federal government, given the legal interpretations that led to the end of racial segregation in Brown v. Board of Education, the legalizing of abortion through Roe v. Wade, the legalization of contraception in Griswold v. Connecticut, and the legalizing of gay marriage — you would think that some national organization would celebrate such profound changes in the Constitution of the United States.

Not the ACLU nor the NAACP nor other organizations, but one organization, the Thaddeus Stevens Society, decided to honor the 14th Amendment.

So, I look to Ross [Hetrick] as not only a fountain of knowledge, but also a strategic developer of how we carry on the importance of Thaddeus Stevens. I first heard of Thaddeus Stevens in high school, when the history teacher defined him as a fanatic. Then I found out that his fanaticism was for the immediate end of chattel and racial slavery and the distribution of land to the freed people. I realized at that time that the real fanatics were Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee, who fought a war that led to 700,000 deaths.

We must re-evaluate even today, what is freedom and what is fanaticism. I always look forward to thinking about Thaddeus Stevens because he wasn’t like a politician today, who would look at the public opinion polls and create a certain message to get another 3% of the vote in order to win a tough race. He was someone who had a principled conviction all his life against white supremacy and against slavery, and making sure there was equality in this nation.

But there’s something else that stood out about Thaddeus Stevens. Sure, there are many people — not often in government — who have decent principles. But how many actually ascend and are able to use a pragmatic way to make his policies effective?

In December 1865, the Confederates wanted to come back into this government. We saw what they did, not only in the past, but the recently enacted Black Codes of inequality in the South. Well, Thaddeus Stevens was real strategic and made sure that the clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives didn’t call their names (the clerk was Edward McPherson from Gettysburg). So what that meant was — it’s hard to believe — but the congressional Radical Republicans had a working majority. I repeat that: a working majority, which is a total necessity to actually get anything done. You can make all the great points, but if you don’t have a working majority, you can’t get stuff done.

And did Thaddeus Stephens and the Radical Republicans get stuff done? More than we can really imagine. Probably in those two years, more profound changes than ever took place in the history of the United States. Even probably, though it’s debatable, more than the New Deal. They made sure that not only the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments passed, but they set up a series of Reconstruction laws that said if you wanted to get back into this country as a Confederate state, you had to do a whole bunch of stuff and give Black men the right to vote. This was before the 15th Amendment.

What that meant was that 500,000 African American men voted in the election of 1868. Many of them voted for their commanders because Thaddeus Stevens had agitated with Frederick Douglass to not only get Lincoln to push for the Emancipation Proclamation, but to make sure that free and escaped slaves could become part of the U.S. Army.

These colored troops fought for their own liberation and helped defeat the South, then came home and persuaded some elected white people that they deserved the right to vote. Then in 1868, 500,000 free African American males voted for Grant with a turnout of 80%, and were able to defeat the 1860s Democratic candidate, Horatio Seymour, whose slogan was “This is a white man’s country. White men should rule.” And to use a phrase from today, “No dog whistles there.”

Now, if we look at what Thaddeus Stephens accomplished, he helped create the Freedmen’s Bureau so that people could actually learn how to read and write and develop their own destiny. He made sure through state constitutions that divorce was changed, roads were built, people could serve on juries, and 1,500 to 2,000 African American officials were elected. So, he had a profound, profound effect on day-to-day life. It wasn’t until later that a sector of the white Republican Party turned against these changes, partly because he proposed that we should not only have political equality, but also economic equality.

C. J. Prentiss. Photo by Larry Miller.

That’s why, when my wife C. J. Prentiss and I walked our dog named Thaddeus, we were able to say to people when they asked, “Why did you name your dog Thaddeus?”, we were able to give a short description of how we not only needed political equality, but also economic equality. In other words, free people needed to be able to have their own power and their own land. But that never took place. If it did take place, we would have a whole different country. Can you imagine if we had economical equality, no racial gap, and the whole society would be transformed into a sector of equality?

Now, my wife also stands out. She doesn’t know I’m going to say this. But she’s one of the only people living who voted to ratify the 14th Amendment. How could that happen? She was a senator in the Ohio General Assembly, and somehow someone discovered Ohio never ratified the 14th Amendment. So, they had a vote. She voted for the 14th Amendment. We live in Cleveland and she worked in Columbus, and when she came back she told me what happened, and I said, “What was the vote?” One person voted against it. Ironically, his wife is now in the Ohio General Assembly, and she’s the lead sponsor of one of those laws that says you’re going to lose your teacher’s license if you teach about racism.

The legacy of Thaddeus Stevens is not only to bring pride to Gettysburg, to serve as a beacon when people from all over the country visit Gettysburg and they can find out the power of Thaddeus Stevens. But it’s even something deeper. As the protests against the murder of George Floyd spread across the country, there arose a movement to get rid of the images of our racist past: the Confederate statues, the names of buildings. And that’s all important. But the symbol of Thaddeus Stephen says that we need to recognize people who fought against racism, white supremacy, and for equality, so people can understand that it’s not enough to just try to wipe out symbols of white supremacy. We must hold up freedom fighters all over the country who actually are willing to do the work.

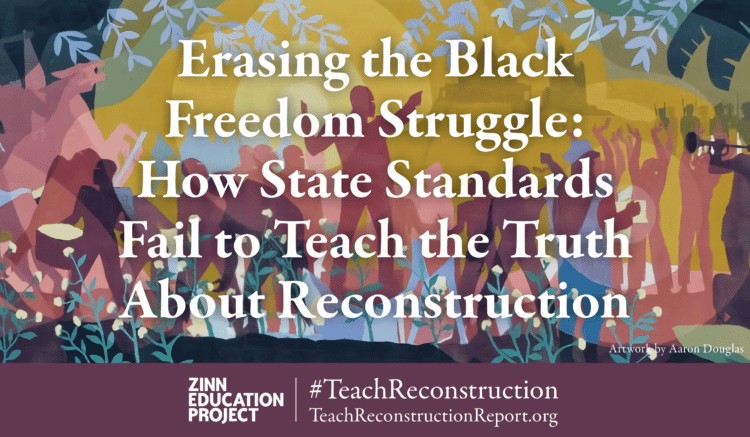

So, in closing, what I hope happens is in every small town, in every city, people get together and find their own local freedom fighter — to be able to give the kind of leadership that the Thaddeus Stevens Society did in Gettysburg — so that when people drive, when they visit, when they learn in their textbooks — as the Zinn Education Project is doing to understand Reconstruction — what’s really important.

We know that we will shortly have a cadre of 15 or 20 teachers, named after C. J. Prentiss and Michael Charney. The Prentiss Charney Fellows will go around the country and spread the word that understanding textbooks and understanding curricula against white supremacy is not enough. What we need to do is figure out how everyone in their own local community can be as powerful as the Thaddeus Stevens Society, and form their own societies dedicated to remembering freedom fighters.

Then we can actually begin (we’ve already begun), but we can even deepen the removal of the stain that Thaddeus Stevens fought every day of his life to end, a legacy of equality and a commitment to undoing white supremacy, not only by ending slavery, not only by redistributing land, but also by having a society that prides itself on being a society of equality. Thank you very much.

Ross Hetrick reading from book that was a gift for Michael Charney. Photo by Larry Miller.

Ross Hetrick: As a token of our appreciation, I want to present to Michael a book printed in 1869, Memorial Addresses on the Life and Character of Thaddeus Stevens. This is my particular favorite quote about Thaddeus Stevens that I’m going to read. It’s pretty short, and this is by Congressman Donald who said:

He never stepped down upon the lower plane of popular error, but at all times and on all occasions he dared to do right, looking Heaven in the face and fearing no man. He never flattered the people; he never attempted to deceive them; he never “paltered with them in a doable sense;” he never courted and encouraged their errors. On the contrary, on all occasions he attacked their sins, he assailed their prejudices, he outraged all their bigotries; and when they turned upon him and attacked him he marched straight forward, like Gulliver wading through the fleets of the Lilliputians, dragging his enemies after him into the great harbor of truth. (pg. 63)

Following these remarks, the statue was unveiled. Read about the event and find photos in “How a guy from 200 years ago showed up in Gettysburg Saturday” in the York Daily Record.

In Meltzer’s biography of Stevens, he went on to explain:

One historian has said Stevens was “perhaps the most despicable, malevolent and morally deformed character who has ever risen to high power in America.”

The harsh judgments his enemies made in his lifetime still echo in the textbooks students use now. What did the man do to deserve this?

He fought to establish free public schools.

He defended fugitive slaves in the courts.

He championed the right of free speech for dissenters.

He spoke up for unpopular minorities.

He led the political struggle to free the [enslaved] and to protect their rights through the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments to the Constitution.

And he tried to reconstruct the defeated South on a foundation of justice for all and a democracy of true equality.

If this is what he stood for, why do so many Americans detest him? Why, for that matter, is Robert E. Lee — who led armies in a bloody war to preserve slavery — called a saint, while Thaddeus Stevens — who warred against slavery — is called a devil?

Dr. W. E. B. Du Bois, social scientist, historian, wrote that Stevens was “the greatest and most uncompromising of abolitionist democrats . . . No man demanded more for Negroes . . . or was more thoroughly an advocate of complete democracy.” Yet “the magnificent figure” of Stevens, he said, “has been besmirched almost beyond recognition.”

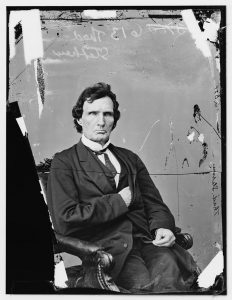

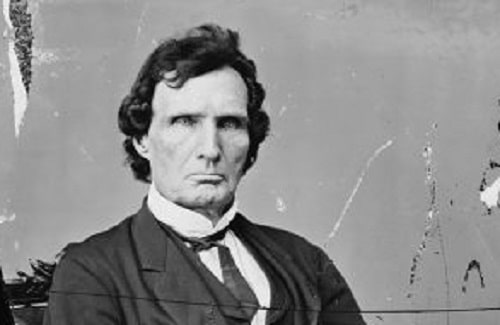

Thaddeus Stevens, 1860. Library of Congress

In Steven’s lifetime the nation confronted a great issue, the right of the Negro to freedom and political equality. He was one of the rare public men who saw it, understood it, and chose to meet it head on.

He made many enemies among those who believed in white supremacy, and those who preferred to straddle the issue and find some way to avoid the pain and cost that justice often entails.

We live in a continuing crisis because the issue which dominated Stevens’ time was never settled.

Much of his work was undone in the generations that followed, but the principles he fought for and the constitutional amendments he helped push through are the ground on which the freedom movement now stands.

To know more about the story of Thaddeus Stevens may help us to understand ourselves and our own time better.

We agree with what Meltzer and Charney said about Stevens and, as our report on Reconstruction reveals, not only Stevens but the whole Reconstruction era get short shrift in most state standards.

Find resources below on Thaddeus Stevens and the Reconstruction era, and on how this period of history is remembered — and misremembered.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn