On May 9, the Zinn Education Project hosted author Kidada E. Williams in conversation with Jesse Hagopian about the imaginative, defiant ways that Black people sought and enacted freedom throughout U.S. history. This history is highlighted in her podcast Seizing Freedom, which focuses on and brings to life voices that have been muted time and time again.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: You all are in for a great evening. So glad you could join us. Some of you are joining us for the first time, and some of you have participated since we launched this series — what, now over two years ago, right after the pandemic began. It is really a gift to be able to share this time together. I want to thank everybody for being in virtual community with us over these years and this evening.

The Zinn Education Project is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change, and we’re hosting this session today as part of the Teaching for Black Lives Campaign that you can learn more about on the Zinn Education Project website. We offer free downloadable people’s history lessons that many of you have used for middle and high school classrooms, from the Zinn Education Project website. I think we have around 140,000 educators across the country in every state registered at the website already. So share the website and the lesson plans.

We are very fortunate today to have ASL interpretation provided by Krystal Butler and Khera Colbert. Thank you for being with us. You can add ASL after your name in brackets for breakout room placements with the interpreter. Since Dr. Williams has presented before, she knows that we are a group of fierce educators in the room today, and parents and students join us, and librarians. So welcome to all. We also have members here of our Teaching for Black Lives Study Groups that are happening all across the country. So, if you’re in one of the study groups, please add T4BL after your name. Throughout the session we want you to use the chat box — you can post questions and comments, resources, ideas. We’ll do a short evaluation at the end, and in about a week we’re going to actually share the full recording of this session with you. Then, I think one of the best parts is you get all of the resources that were shared in the chat box. So, we’ll compile that list, and you’ll have so many more resources to teach this history in your classroom. We also want to encourage you to tweet about what you’re learning today — post on social media what you’re learning and encourage others to join these monthly classes. Then after about 25 minutes, we’ll pause so you can meet each other in small groups and process what you’ve learned and think about how you might use it in the classroom.

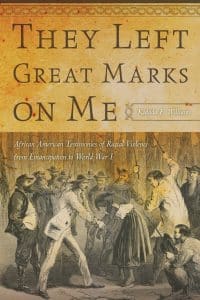

Now I am really excited to welcome Kidada Williams, author of They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I. She’s also the producer and host of the great podcast Seizing Freedom. Dr. Williams, welcome. Thanks for being with us.

Kidada E. William: Thank you so much for having me and for covering this amazing topic.

Hagopian: No doubt. I’m so excited to dig into this illegal history with you, as it’s become in so many states. I think it’s now 42 states that have laws and are trying to ban history. Or, I think as you put it before the session started, these white comfort laws that want to mandate that we lie to kids about structural racism. I’m so glad that many of us are refusing to do that, and there’s a lot of leaders here with us today in that struggle. So, I’m excited to dig into this history with you, and I think it’s so incredible that you’ve started this Seizing Freedom podcast. I’ve really enjoyed the podcast. The script writing is so engaging, the production quality is off the charts. I feel like I’m watching a play when I’m listening to all the soundscapes and the different voices that bring to life this history of the Civil War, of Reconstruction, resistance to lynching, just the ongoing Black Freedom Struggle that you document so well. I just wanted to start tonight by asking you why a podcast? What does that medium allow you to do? And then, I’m also curious if you could comment on why this medium would be good for educators. How can we use your podcast and other podcasts to encourage students to make their own? What’s useful about it?

Williams: So I love podcasts, even before I started hosting one. I think the medium allows you to deliver and receive a diverse range of information. You’ve got a combination of scripted narratives, like Seizing Freedom, and also arresting conversations with really smart people. I think history podcasts, in particular, are doing some of the most amazing storytelling work out there. What we have is rather than simply watching yet another screen — we know we’ve all been sort of committed to our screens during the pandemic — teachers and students can listen and imagine themselves in whatever time or place is being discussed. So podcasts, I think, engage our senses and our brains in different ways. Like our brains receive and process information when we hear it, when we hear the information differently than it does when we’re looking at it. It’s slower, and I think it kind of sinks in.

I think a show like Seizing Freedom is a great example of this. We tell a new and very accessible history of African Americans’ fight for freedom, using a mix of the best scholarly research that’s out there and some of the most engaging stories from the men and women who fought for freedom. We’ve got these letters, testimonies, newspaper reports, autobiographies, and all of these other sources to tell the story, and our voice actors bring these amazing people and these stories to life. Students and teachers can listen to the emotion behind the text. A self-emancipated man who’s asking to enlist, like Harry Jarvis. A father determined to get his daughters back. Through these sources, I think that students and teachers can get a greater sense of who the people were, who these people were, who completely changed the course of American history. I think teachers can create classroom exercises, but it’s guiding students into a much deeper analysis of the sources. We give you a little bit, but the larger sources are available for examination in the classroom. So, that’s what I kind of think podcasts do.

Hagopian: I love that. I love what you said about bringing the emotion behind the text. And the textbooks they give us to teach out of are just so dry, right? Forget the fact that they lie to kids, right? They’re just straight up boring from whatever perspective that they’re examining. And your podcast really does bring that emotion behind the words, I think in a way that would be highly engaging for youth.

So, I wanted to start by asking more about the master narratives that you explore in the Civil War. These were master narratives that were taught to me, and are taught to the vast majority of students — the idea that Lincoln freed the slaves. But the reality is, as you say in the podcast, “Black people north and south, free and enslaved, were active agents in their own emancipation, before, during, and after the Civil War.” So, I was hoping you could talk more about how Black people, men and women, participated in seizing their freedom from slavery. But, I wanted to just start by playing four short excerpts from your podcast that explain this point and then ask you to elaborate on that, if it’s alright with you. Excellent. Because I hope everyone will get an understanding for what a powerful tool this podcast could be. We’re going to start with Harry Jarvis, who had run away from the Virginia plantation on which he was enslaved.

Recording of Harry Jarvis: “I went to him [the commanding officer at Fort Monroe] and asked him to let me enlist, but he said it wasn’t a Black man’s war. I told him it would be a Black man’s war before they got through.”

Hagopian: Now we’re going to hear from Cornelius Gardner, a formerly enslaved soldier in Virginia.

Recording of Cornelius Gardner: “Frederick Douglass told Abe Lincoln, ‘Give the Black man guns and let him fight.’ And Abe Lincoln say, ‘If I give him a gun, when it comes to battle he might run.’ And Frederick Douglass say, ‘Try him, and you’ll win the war.’ And Abe said, ‘All right, I’ll try him.’”

Hagopian: Man, I’m glad Frederick Douglass said that. Susie King Taylor, a formerly enslaved woman who worked for the first South Carolina volunteers, the first Black regiment in the U.S. Army.

Recording of Susie King Taylor: “I assisted in cleaning the guns and used to fire them off, to see if the cartridges were dry, before cleaning and reloading, each day. I learned to handle a musket very well, and could shoot straight and often hit the target. I thought this great fun. I was able to take a gun all apart and put it together again.”

Hagopian: Right on. And then Rosanna Henson to Abraham Lincoln.

Recording of Rosanna Henson: “My husband who is . . . now in the Macon Hospital at Portsmouth with a wound in his arm . . . has not received any pay since last May and then only thirteen dollars. . . . I have four children to support and I find this a great struggle. A hard life this! I, being a Colored woman, do not get any State pay. Yet my husband is fighting for the country.”

Hagopian: So talk about what these all represent.

Williams: You mentioned the master narrative. There is this whole mythology about Black people in the Civil War and Reconstruction eras — it goes that they sat passively waiting for white people to free them from slavery, that Reconstruction failed. These are the stories that many white Americans have told themselves and anyone who would listen. But professional historians for the past couple of decades have known that the historical records of the time tell a very different story. And you could hear that in these clips. These are people who did not sit, African Americans who did not sit, passively waiting for anyone to free them. They freed themselves. They’ve got hundreds of thousands of people self-emancipating during the war, they are fleeing bondage like Harry Jarvis, they’re showing up in Union camps like Susie King Taylor, and they are doing what they can to join the Union effort so they can secure their freedom and that of their people. So you’ve got this master narrative, but that narrative serves a particular end to this story. When you look at the history of the Civil War from the perspective of the Black people who were living in it — who changed the course of American and African American history through their fights for freedom — it’s not only a more accurate story, but it’s a different story. And it’s a story that actually makes more sense for understanding the nation at the time and the world we live in today.

Hagopian: Yeah, I love that. You know, I heard the desertion of Black people from plantations during the Civil War described as the largest general strike in U.S. history, and that that’s what finally brought the Confederacy that was winning the war down. And that’s not what I was taught at all. So I really appreciate that. Everyone should check out that podcast episode, for sure.

Then your work around Reconstruction, I feel like, is some of the most important, and it’s become a focus of the Zinn Education Project. We just released a report on the state standards on Reconstruction that are just abysmal, so I especially appreciated your Reconstruction podcast. You tell the story of a 17-year-old enslaved person named Mary Armstrong, who lived in Missouri, which was a Union slaveholding state during the Civil War. She got her free papers in 1863, the same year of the Emancipation Proclamation, targeting slavery and states that had seceded. She thought that her mom might be living in one of those states in the Confederacy, in Texas. And so Mary decided to set off, and you tell this incredible story, to go look for her mom. She almost gets re-enslaved in Texas, but she manages to escape. I was hoping that you could talk more about the experiences of hundreds of thousands of freedpeople during Reconstruction in their quest to reunite with loved ones. And just before you say that we could play a short clip from Mary.

Recording of Mary Armstrong: “In 1865, Mary resumed her search for her mother. I found her in Warren County, Lord me talk about crying and singing and crying some more. We sure did. I stay with Mama until I got married.”

Hagopian: Yeah, talk about what it was like in this quest to reunite with family.

Williams: We know that many families are broken up after the American Revolution. Enslaved people’s families enjoyed relative stability before the American Revolution, but after the revolution, especially with westward expansion, we start to see more and more families along the eastern seaboard broken up. Even more, as you get more westward expansion, and slavery takes a greater toll, families are devastated by these separations. So it would make sense that they would use the chaos of the war to not only escape, but to go in search of their people. This makes sense when you understand that they didn’t see themselves as free or completely free unless their people were free. How can you as a daughter be free if your mother is still in bondage? As a father, how can you enjoy your freedom while your children are still held in bondage? So these ties, that sense of family, this kinship is what’s driving that search for family.

And people like Mary Armstrong, they take risky moves. She’s a 17-year-old girl — imagine it, she takes off, she gets on a steamboat going south, she goes from camp to camp, town to town, working along the way to find her mother. She’s one of those people who was actually able to do what she had to travel much further. And a lot of people who have to travel that distance are not successful. But there are many people who are, and it’s one of the most — I think, for me — it’s one of the most amazing stories of the period. It shows their commitment to their people, their sense of their collective freedom and their collective fate. They would be able to make freedom real only with their people. They’re not going to be able to do it on their own, they need kin, they need neighbors, they need community to do this work. And so it’s one of the many inspiring stories that we tell.

Even if they don’t have to go in search of kin, what we see is that they’re finding new people, they’re starting new families. Potentially, because you’ve got fairly young people, they’re meeting up and they’re making free lives together, and they’re doing what they can to build a new world. But even as they build this new world, one of the most amazing things, I think — and why we have a story like Mary Armstrong’s in the first place — is because they told the future generations, they preserved those stories of who they were. They passed those stories on to their children and their grandchildren about who they were as individuals, and who they were as a people, and what freedom meant to them. And those are the histories that have been ignored or excluded as a result of the master narrative of the Civil War and Reconstruction. But they’re there and they’re available for teachers to use, for teachers to read, for teachers to share with their students and develop lesson plans to help understand the world as we know it today.

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. This episode is just so moving, and just puts you in that place and helps you think about the emotional weight of searching for a family member, never knowing if you are going to be able to reconnect or not, and just the way Black people had to construct their families differently because of this oppression. Thank you for sharing that for sure. One of the episodes I most appreciated regarding Reconstruction was the episode about literacy in schooling during Reconstruction. I hope everyone will listen to it in full. It’s especially important to me because the work I’m doing right now on the history of Black education, just hearing those quotes from people seeking their education just really brought out, as I told you before the session started, that quote from Du Bois who said that Black education, or education in the South, was a negro idea and that Black people built the public school system in the South.

I feel like this so vividly illustrated a couple of things to me. First, how despite the narrative that Black people don’t value education, perhaps no one in the history of this country has fought harder for access to it. Then second, all these bills banning history, banning the truth, aren’t the first time that Black education has come under a sustained assault. So, what was the importance of literacy in the postwar South, and how did free people pursue and use education?

Williams: Well, I think it’s vitally important and they understand that education, and what they mean by that is reading, writing, math, knowledge of the world — beyond farms, plantations, homes, businesses, where they were held in bondage — that this education, this wider education, is essential to their freedom. We noticed that many of them had been privy to the first education about who they were, about their family history, about local geography, religion, and more. They’re not ignorant. I think we need to be clear on that. They just lacked formal education. And there’s a difference.

Another statement that Du Bois said is that the white South knows an educated negro is a dangerous negro, because an educated negro is always going to resist her and his oppression. And Du Bois’s follow up behind that was, “and they were not wrong.” Only five states pass laws prohibiting the teaching of enslaved people to read and write. And that was fairly late in the history of slavery. But most enslavers denied Black people access to formal education as a method of control, to keep them in bondage. But that didn’t stop Black people from doing anything and everything they could during slavery to learn how to read and write. They self teach, they teach themselves, they pick up literacy wherever they can, they get formal training, [and] they pass any knowledge they have on to other people. They use their educations to read the Bible for themselves, to read the nation’s founding documents for themselves, to free themselves, to write passes for travel, to write passes to free themselves, to escape from bondage, to secure employment. They use education in all of these ways, and that’s why that value of education is something that existed before the war and during the war.

We see evidence of that by the fact that you’ve got the establishment of schools in refugee and Freedmen’s camps during the war. They’re not waiting passively for the war to end. Those people are self emancipating. They see freedom on the move. Even in the camps, the refugee camps, where they are, they are in the process of making freedom to the best of their ability, wherever they are. That means getting married, that means reuniting with family, that means going to search for their people, and it means opening schools to start that instruction process. That thirst for education is why you see newly freed people creating schools before the Freedmen’s Bureau even shows up.

I think that’s an important part, that they’re doing that work themselves. They’re paying the teachers with chickens, with hogs, etc. They’re like,” We will build a school. We might not have cash, but we’ve got these other things that we can provide you.” And the teachers are happy to accept that money. Then when the Freedmen’s Bureau comes in, what we see is that the freedpeople don’t surrender their schools voluntarily to the Freedmen’s Bureau. They want a say in who the teachers are, how they’re going to treat their students, their children, and what they’re going to learn. What we see is that they’re not just interested in reading, writing, and arithmetic. In these Freedmen schools, they’re learning history, geography, art, literature, world history, national history. That education is much more expansive than we thought.

In our conversation with historian Hilary Green, who researched these schools, details that. I think teachers can get from the narrative episodes, a sense of the history, and from the interview episodes, a sense of the scholarly conversations, and sometimes a deeper knowledge of the history that goes into the episode. Our conversation on camps with Abby Cooper — Abigail Cooper is the scholar who found Mary Armstrong’s story and fleshed out those details. So, if you want to know some of the behind the scenes history, some of the richer history behind the narrative episode, you can listen to the interview episode, because we get into all of that.

Hagopian: That’s great. I love some of the discussion too, about the struggle over what students were going to learn in those schools, and the white missionary educators having a very different idea of what it meant to be educated than Black educators who came in wanting to empower that route, and weren’t shocked that Black people had intellect.

Williams: Exactly. Right. You know, some of the white missionaries, they only want them to gain the basic skills so they can be of service, so they can be of service to white people, to the nation, etc. But Black parents have a much bigger and much more expansive vision for their children and their future, and they do what they can to fight to make that possible. We see, even after Reconstruction is overthrown, even in those schools, you still have until the early part of the 20th century, Black teachers who are teaching this really expansive, rich history.

Hagopian: Yeah. In some ways I feel like that still hasn’t ended. The struggle over what the purpose of education is and the fight for Black education in our buildings doesn’t look all that different than some of the live debates during Reconstruction. Right?

Williams: Except we’ve got the benefit of their experience. So we know the content. We know the ways they fought, we know the ways they held onto some authority and power to the best of their ability, to continue doing that work. And we’re doing some of the same kind of work today.

Hagopian: That’s great. So, I wanted to ask you one more question before we move into breakout rooms. And we’ll give people an opportunity to talk about some of the things they’ve learned, and then they’ll come back and we’ll answer questions. But the episode called Walk! The Streetcar Boycotts! is just so fascinating. I knew like a broad sketch of some of that, but really didn’t understand how central struggles to desegregate public transportation were to early fights in the Black Freedom Struggle. Because between 1900 and 1910 you talk about how Black people in more than two dozen cities organized boycotts of streetcars as one strategy for fighting against the new Jim Crow laws and for greater access to public life. When these new laws passed in Houston, I love the story that you tell, that the segregated public transportation led to a funny story of a white man who tried to get a ride from a Black person who refused him a ride. And so . . .

Williams: He said, “I cant’ take you. You know, the new law says, I can’t take you. Sorry about that.” For me, you’ve got to find another way to work, right? But I also love the stories of Black people throwing rocks at the streetcars in protest, showing their frustration with segregation — but also their very crystal clear sense of community responsibility and their policing of anyone who stepped out of line — cross that line, you get on that street car if you want to.

Hagopian: That’s right. I mean, just the creativity of the Black Freedom Struggle comes through in this episode so clearly. I was hoping you could talk more about the role of segregating streetcars in establishing Jim Crow and also about the movement in Houston, but really all around the country, in challenging these laws, and how our understanding of the Civil Rights Movement really is transformed when we think about the Montgomery Bus Boycott launching the Civil Rights Movement. But very few people know this history from much earlier.

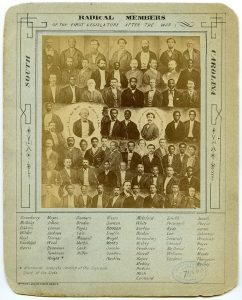

Williams: I’m going to try to be really efficient, because it’s a little complex. What I mean by that is white Americans didn’t support or need segregation during slavery. They want close, intimate proximity to Black people so they could control and dominate them, so they could hold them in bondage, so they could steal their lives and labors. Emancipation completely changed this dynamic. The Reconstruction acts and amendments gave Black people an opportunity to advance, and Black people ran with it. They get education, they open businesses, they acquired land, they were elected into office, they do all the things. And white supremacists are furious because they had told themselves that Black people were inferior. But a few years out of the gate of emancipation — and despite all the white violence and white racist grievance — Black people are still making significant strides. They’re making the kinds of strides that they can enjoy — access to leisure, access to food, so they can buy first class tickets and accommodations. And they can do this while some poor white folks can’t.

White supremacists want none of that. So, we start to see them passing laws in these specific places where Black working class and middle and aspiring class folks are advancing and are able to show signs of significant progress. They target them with surgical precision. And that’s where you see streetcars come in. Everyone isn’t taking streetcars. Some people don’t have the money. You think about the cost of public transportation during that time period. These aren’t people with money to take the streetcars. So what they want to do is limit their access, to shut them out, to make them know their place in the society, as below white people. African Americans fight these laws wherever they are. They see them as violations of their rights and infringements on their dignity, in public places that they are forced to sit in the back of the bus, etc. African Americans have been fighting this since Reconstruction.

But the Plessy ruling said that states, businesses, public goods, etc., could be segregated as long as they were equal. But white supremacists made sure they were never equal. So, if we look at this history of how segregation is built, Jim Crow, we also see Black people’s protests, protests of segregation, and protests of segregated public transportation. This didn’t start in the 1950s in places like Montgomery. Black people have been fighting since the very beginning. And this is where you get those series of boycotts in the cities. And in most instances, the cities just wait the protesters out. But in Richmond, activists are successful enough that they shut down the streetcar company. I think that that’s important [to show that] they did have some victories, but they couldn’t stop Jim Crow. And it’s impossible for them to stop Jim Crow in the South with the vast majority of Black southern men disenfranchised. So, disfranchisement happens first, segregation comes and expands in much greater detail after that.

So, what we see is that Black people are not fighting to be in physical proximity to white people, and I think that’s an important thing that we need to make clear to people. They didn’t believe that white people were somehow magical. They knew that physical proximity to white people exposed Black people to violence. What Black people wanted was for states and cities and businesses to respect the equal doctrine of Plessy. But respecting the equal doctrine undermined white supremacist ideas of their supposed superiority, so they universally rejected all calls to respect the law of the land — which is that if it’s going to be separate, it’s got to be equal. It’s only when they refuse to even do the bare minimum of equality that we start to see Black people pressing for full desegregation. I think knowing this history of earlier fights against segregation helps us understand what happened later on in the Civil Rights Movement.

Hagopian: For sure. I just was thinking, the Montgomery Bus Boycott organizers, were they aware of the victory in Richmond, Virginia? Is there any documentation of that that you’ve seen?

Williams: I don’t know that they were aware of it. They might have been aware of those earlier boycott campaigns and they may have possibly learned about them in their schools. They may have been passed down from family members who maybe migrated to other places. It’s not clear that the organizers of the boycott — people like Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, Mary Fair Burks — it’s not clear that they know for sure, those earlier histories, but they might have. We just don’t know.

Hagopian: Interesting. Love to talk more with Jeanne Theoharis on that as well.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Responses and Highlights

Here are a few reactions from participants:

I LOVE the idea of using the podcasts as a way of using storytelling, rather than having kids read stories. It puts a voice to the words and humanizes the experiences!

These workshops are always fabulous. Always, every time, every single one. I always learn a lot, and what I learn regularly informs and shows up in my teaching.

I’m very excited to get into the podcast and find pieces to share with students as additional voices for our classroom — especially the highlighted role of Black women that is so absent from many sources.

I love the format. The breakout rooms are important to give folks an opportunity to find out who is in the room and to learn what is going on in different states.

Of course, I loved all the wonderful new (to me) information she shared, and the energy with which she told the stories. But I also really appreciated that the voice-over talent used in the podcasts actually spoke with authentic Southern voices. They were not Northern actors who mangled the “accents” (and I can say this as a Black northerner myself who never could get it right, even after all my time working in the South).

Audiogram

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, articles, and more recommended by the presenters and also by participants.

Lessons and Curricula

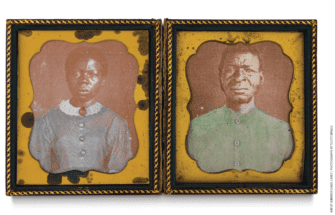

|

|

Teaching With Seizing Freedom by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca Poetry of Defiance: How the Enslaved Resisted by Adam Sanchez Reconstructing the South: A Role Play by Bill Bigelow When the Impossible Suddenly Became Possible: A Reconstruction Mixer by Adam Sanchez and Nqobile Mthethwa Teaching a People’s History of Abolition and the Civil War edited by Adam Sanchez (Rethinking Schools) |

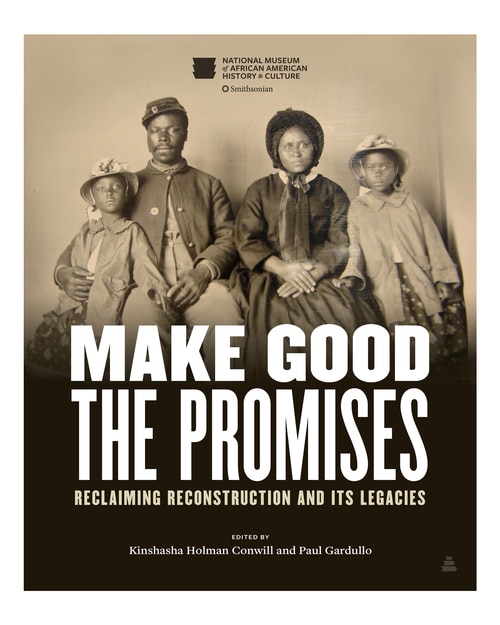

Books

|

|

In addition to Kidada E. Williams’s They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I, the following books were referenced: All Bound Up Together: The Woman Question in African American Public Culture, 1830-1900 by Martha S. Jones (University of North Carolina Press) The Brownies’ Book (a monthly magazine specifically written for African American children) Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination by Robin D. G. Kelley (Beacon Press) |

Articles

|

|

“Black Students are Caught in the Middle of America’s Culture Wars” by Melinda D. Anderson (Huffington Post) “Wake Up the Sleeper” by David W. Blight (Education Next) “We Are All Bound Up Together” by Francis Ellen Watkins Harper (BlackPast) |

This Day in History

|

Jan. 14, 1868: South Carolina Constitutional Convention Feb. 3, 1868: First Freedmen’s Bureau Teacher Appointed in Lafayette Parish Sept. 3, 1868: Henry McNeal Turner Addressed the Georgia Legislature Dec. 9, 1872: P. B. S. Pinchback Becomes Governor May 5, 1905: Chicago Defender Founded |

Participant Reflections

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

The most important thing I learned today is that this podcast is beyond amazing. I have listened to a few episodes and have used a couple this semester. My students love them. I will definitely continue to use them and spread them to other teachers. The fact that these episodes are so well researched and the voice acting makes history come to life by listening to them.

The quick structure that Dr. Williams shared for discussing the complexity of the different forms that resistance to segregation and Jim Crow took post-Plessy was useful for thinking about how to present this complexity to students. In general, I’m looking forward to listening to season two of Seizing Freedom for a guide to doing the work to make the connections between Reconstruction and today that doesn’t just jump to the 1960s.

How important it is to continue to learn and teach about the myriad contributions of Black people in social movements, as well as pre-and post-Civil War.

That during slavery, many of the enslaved — even once they’d gained their freedom — didn’t consider themselves free until others in their family were also free. It supports the scholarship that notes that most of those escaping enslavement weren’t running to “freedom,” they were running to a nearby (or farther) plantation to see family members they’d been torn from. That sense of community and kinship is so important, particularly in modern times when the Black family is portrayed (even before Moynihan) as not (and never) whole. I also loved the story about the woman who learned how to clean a musket.

What will you do with what you learned?

I’ve been using Seizing Freedom in class (2-5 clips, paired with reflective writing and group projects) and next time around I want to figure out a method for doing some student-led research into the primary sources used in Seizing Freedom. This semester, students are doing a different project, but Dr. Williams’ suggestion to use the podcast as a means to encourage students to explore the wealth of primary sources is an excellent one — it will just take some time to figure out how to best guide 8th graders in that process.

I will use more of the episodes as a warm-up or even as exit tickets for my students. I discovered that they really do enjoy podcasts. They can listen while on the bus and they are learning at the same time.

I will first deepen my own knowledge by listening to the podcast and then I think it would be amazing to have my 5th graders do a reading of first person quotes that are impactful to them.

Next school year, I will start taking over U.S. History in my school for the first time. We have a “brand new” curriculum which starts U.S. history at the “Gilded Age” and does not even mention Reconstruction. However, since I get to be the first to teach and build this class for our school, I have the opportunity to really build something new. I am compiling a wealth of resources over this summer and have Seizing Freedom on my list of things to dig in to. I love using podcasts in class because audio is such a powerful literacy tool for all students. I think these podcasts do such a beautiful job of illustrating for students what great scholarship looks like and the power of primary sources.

Presenters

Kidada E. Williams is the author of They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I. She teaches courses on African American and U.S. history and historical research methods at Wayne State University. Williams is also one of the co-developers of #CharlestonSyllabus, a crowd-sourced project that helped people understand the historical context surrounding the 2015 racial massacre at Charleston’s Emanuel AME Church.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, and editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn