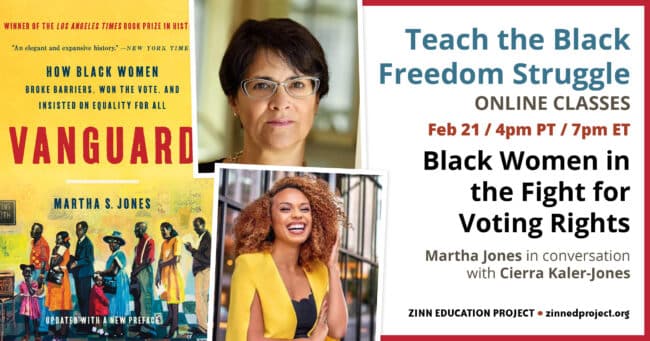

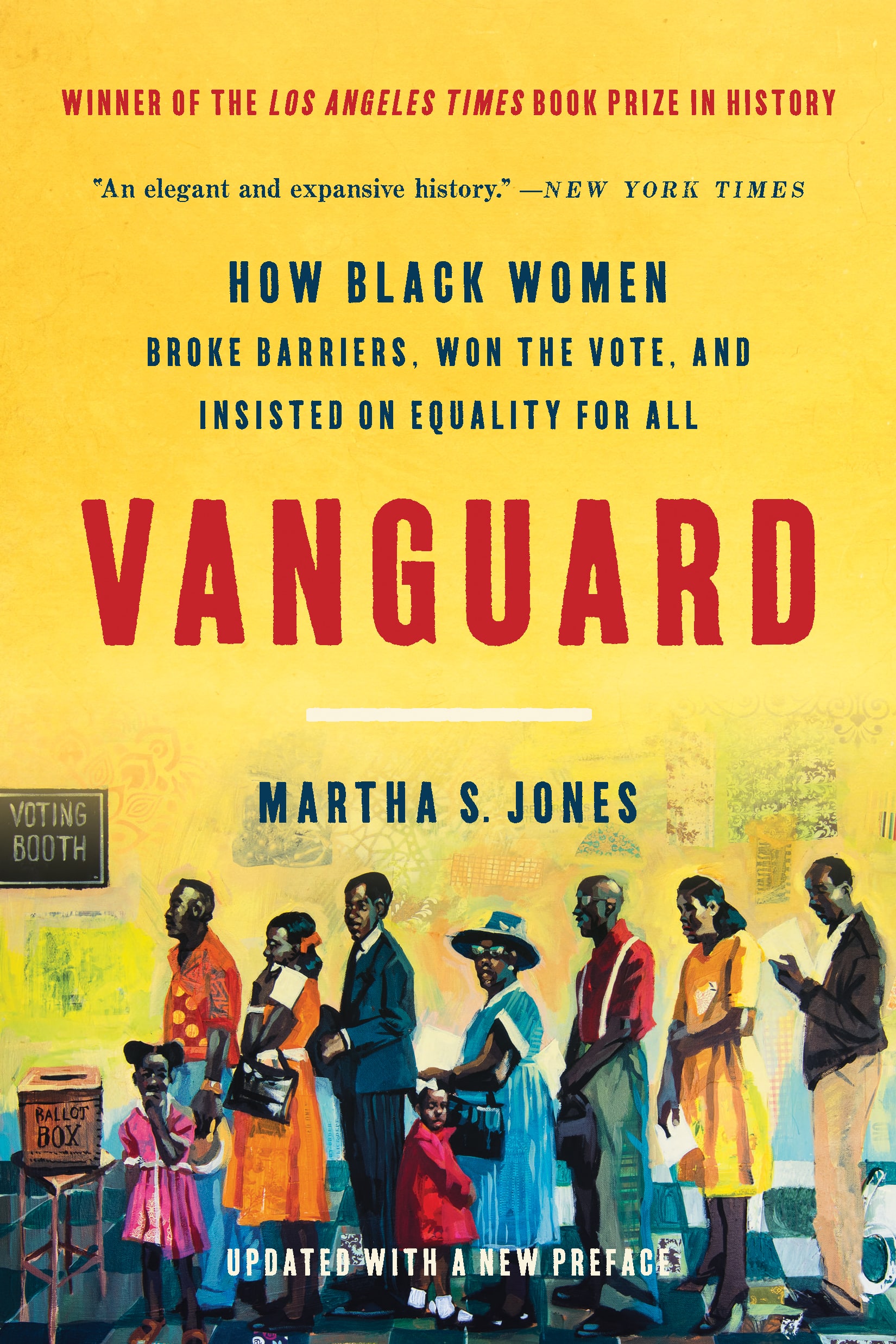

On February 21, the Zinn Education Project hosted historian Martha S. Jones in conversation with Cierra Kaler-Jones about the role of Black women in the long and ongoing fight for voting rights. This class was part of the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online series. Thanks to a donation from the publisher, the Zinn Education Project was able to give copies of the new paperback edition of Jones’ book Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All to 20 teachers who attended the event.

Here are a few reactions from participants:

So many intriguing ideas and perspectives, but what is standing out to me tonight is the idea of joy. So often in working with history and different perspectives, I focus on the challenges, the struggles. Bringing forth stories of joy, even (or especially) amidst the intense struggles, and joy as an essential element of our shared humanity, weaves together so many of the threads of different peoples’ experiences. Finding and highlighting the joy and happiness that often are there are ideas that are inspiring to me as I continue deepening my own knowledge of all this history and sharing it with others. Thank you.

The stories of our female ancestors are powerful and need to be told and taught! Using Vanguard I can share with my students the background of the struggle for Black women to vote and tie it into what is happening currently all across the country. This history is bigger than us.

I am saying yes to being an Alternative Election Judge for my community during next week’s Primary Election. I was wavering because of my schedule. But what can be more important than showing up as a Black woman to represent those who have gone before me — putting my voice, face, and yes, privilege out there to inspire others.

One of the things I learned today is how important it is to teach about the many different issues Black women have always organized around. There were not a lot of Black women who did single-issue organizing because they saw the complexity of the interlocking injustices they experienced every day.

I was most inspired by the idea that power comes from knowing you’re right. I came of age in the 1960s and never thought that in 2022 we had to nearly start all over again. Dr. Jones motivated me to never give up.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Cierra Kaler-Jones: Welcome! We would love to welcome everyone to our class with Dr. Martha S. Jones. Some of you are joining for the first time; I saw about 40%. So welcome, we are so glad that you’re here. And some of you have participated in our spring series; I saw about 40% of folks have been to almost every session. So welcome back again. We’re just so grateful to be able to learn together. It is a gift to be able to share this time together. And again, just thank you so much for being in virtual community with all of us. The Zinn Education Project, coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change, is hosting this session today as part of our Teaching for Black Lives campaign and Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online series. We offer free downloadable people’s history lessons that many of you have used. I’ve used many of them as well for middle and high school classrooms from the Zinn Education Project website. The ASL interpretation is provided by Krystal Butler and Tyriibah Royal, and if you would like ASL for the breakout rooms, please do add ASL after your name in brackets for the breakout room placement with an interpreter. Before we begin our conversation, we really just want to find out who is in the room and we’ll go through the plans for our time together. We’ll post a quick poll to find out how many teachers, librarians, teacher educators, historians, parents, students, and others are in the room with us. Many of you are in multiple roles, so please just pick your primary one. And you can go ahead and introduce yourself in the chat box so that we can get the conversation rolling. I see some are coming in now. I see K through 12 teachers are in that house. We have students, lots of teacher educators, historians, shout out to the librarians, family members. And we also have members here from our Teaching for Black Lives study groups. So if you are in one of those groups, please add T4BL after your name. Okay, I see the poll is being shared. We have 49% K through 12 teachers, so much love, gratitude and solidarity with all of you. Thank you, thank you, thank you. We have 4% students, 1% family members of a student, 17% teacher educators, 9% historians, 1% librarians, and 19% others. So thank you all for being here, and go ahead and introduce yourself in the chat. Throughout the session, we want you to use the chat box to post your questions, your comments, resources, and ideas. And we’ll do a short evaluation at the end. In about a week we will share the full recording from the session and all of the resources shared in the chat box. Also, please tweet what you are learning. You can go ahead and use the hashtags #TeachBlackFreedomStruggle and #TeachTruth. I don’t know about you, but I am so ready to start this conversation. After about 25 minutes, we’ll pause so that you can meet each other and talk in small groups to share your thoughts with one another. I am so honored and so blessed — we are all so honored and so blessed — to be joined by Dr. Martha S. Jones, the Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor and Professor of History at Johns Hopkins University. Her books include Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All, and also Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America. I was telling the ZInn Education Project team that as I was reading this book, I feel like, Dr. Jones, I could be in conversation with you for hours and there would still be more stories to share. So I really am just so thrilled to be here with you and to be able to highlight some of the stories of the women of Vanguard. Now we’ll just jump right in. So, many of the stories about women’s voting rights start at the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, but Vanguard actually takes us back to the late 1780s with stories of Black women like Jarena Lee. So, for all my Jersey folks in the class today, Jarena Lee is from New Jersey, so I was really excited to read that. Vanguard also takes us up to the present day struggle for voting rights. So, what does the narrative about the women’s right to vote leave out when it starts in 1848 and then ends in 1920? Martha Jones: First of all, let me say thank you to you for sharing the evening with me. You’ve taken such care to get us here and to make sure we have a rich and important conversation, so I thank you so much for that. And thank you to Zinn Education Project. It’s great to be back with you all. It’s really an honor to feel like this is a home for me and for the work, and for the kind of conversations we need to have about the past. So welcome, everyone, I’m just really thrilled to be here. One of the early lessons in trying to write the story of voting rights in the United States through the perspective of Black women was that I couldn’t end at 1920 with ratification of the 19th Amendment. Now, I think a lot of us may have learned that story somewhere along the way, and I think even when I contemplated the book, I initially thought that’s where I would end. But I very quickly discovered, of course, that the 19th Amendment is a milestone, but a disappointing one for Black women, and that I couldn’t tell the story if I couldn’t bring it all the way to 1965, the year they won the Voting Rights Act. But of course, as we all know, the Voting Rights Act doesn’t settle the question, the problem, the trouble with voting rights in the United States. And so, in a sense, it’s a book that doesn’t end. There’s a new paperback edition, which I know some folks have seen, where we try to bring it up through the election cycle of 2020. Even that has sort of been eclipsed, right? Which is a testament, I hope, to the relevance of the book, but it is also a testament to how fraught voting rights continue to be in this country. Yes, Jarena Lee, lots of folks are surprised that I begin this book, it’s 1820, we’re following a Black woman preacher in the African Methodist Episcopal Church as she treks across many places, looking to preach. But in fact, I was in search of a foremother that would help us understand the ideas that animate Black women suffragists ultimately in the story, and Jarena Lee is a woman who is perceived by some to be out of place and out of time, because she’s called by God and she is going to preach. And it turns out she’s a terrific preacher, not just any old preacher. So she writes a memoir and that’s how we know her story. In that memoir, she’s already in the 1830s wrestling with the problem of racism and sexism, of the intersectional dynamics that are produced out of those two. So I had to begin there. I wanted folks to appreciate that when you’re looking for Black women in history, you have to go where they are, not where you think they should be. And in her case, she’s in the AME Church. Kaler-Jones: Wow, I love that story so much. Particularly when you are talking about this point in history, you’re also talking about how many men were afraid of what would happen when Black women took the pulpit. They began to organize to ensure that they were able to share their stories and share those key pieces of themselves, and then their testimonies, as part of the church. So I really appreciate that, and I really appreciate what you said about going where they are. Another thing that you mentioned when you first started, you began to share with us is how the new version or the paperback version takes us up through today. So as we think about the current moment — and as many historians have named one thread of history that continues today is that Black advancement is always met by white supremacist Black-lash. In the book you discuss how at the 1837 national political convention In Philadelphia, Black women were met with violence for their anti-slavery organizing. Then later on in the book you also talked about the violence that Fannie Lou Hamer and many others face at the hands of local officials, and we see this same violence today, whether it be physical violence, or even the emotional violence that is many times enacted onto Black folks. So what is the steep price paid for voting rights? Jones: The thread of violence that runs through this story was one of the things that I learned in writing this book that I hadn’t understood, how ever-present, how consistent, how, in a sense, essential, violence has always been to the suppression of Black voting rights for Black men, but for Black women also. So for me, I guess one way to think about how violence figures and how we respond to violence is to appreciate that every generation faces its own version of that challenge, and that violence need not be visited on every individual to reverberate through a community. Sherrilyn Ifill has written magnificently about this in her book called On the Courthouse Lawn, and Ifill looked at how Black votes on the Eastern Shore of Maryland were not suppressed, but were not where they should be in the wake of the Voting Rights Act. What she discovered was how the memory of lynching, even in the next generations, kept Black voters in Maryland’s Eastern Shore home on Election Day. So I tell stories that I hope are not only illustrative, but give us our own sense of what happens when violence is visited on our neighbors, when violence is visited on our communities, when violence is visited on our families, that has an effect far greater right than at any one moment. And I think that the women in Vanguard not only experience that [but] they build a politics in response to that, because what they are willing to do, certainly by the 1860s, is to speak that, and to claim and assert that right. The threat of sexual violence is what’s keeping us from claiming our full political power, and they need a political movement that will speak to that, as well as to many other forms of suppression that are combating Black communities. Kaler-Jones: Absolutely, and keeping up with this thread of our history continues to show up in the current moment, the Zinn Education Project recently released a report on how state standards fail to teach the truth about Reconstruction. And we can’t understand the current moment and what is happening without grounding ourselves in the history of Reconstruction. So, what was the role of Black women in the significant gains to Black political power during Reconstruction? We’ll drop the link to the report into the chat box so everyone can check it out. Jones: The report is terrific, and I’ve been sharing it myself. I’m glad folks will have a chance to check it out if they haven’t seen it. So here we are in these remarkable years following the American Civil War, slavery has been abolished, and there is a major question on the table for not only formerly enslaved people, not only for Black folk, but for all Americans. What is freedom? What is citizenship? What does it mean to belong? What are the parameters of that? And of course, Black Americans are going to be the ones who are pressing these questions and pushing on the limits of what is freedom and what is citizenship. Black women are going to be at the podium. By 1866, in the immediate wake of the war, at the war’s end, to claim, for example, political rights, to claim themselves as among those who should now move fully and unequivocally into the center of political culture in the United States. For me, the great poet, anti-slavery lecturer, educator, Francis Ellen Watkins Harper stands up at the podium in 1866, and she says, “We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity.” Now, Watkins Harper is infinitely quotable, because she was indeed a poet and she had a capacity with words. That means we borrow them frequently. But this phrase is a window into how she is thinking about the future in the United States. And what she’s thinking about, yes, there’s her own political rights, but she’s thinking about human rights and she is setting the bar high. In a room where there were those who were advocating that Black men should get the vote first, others who were advocating Black and white women should get the vote. First, Watkins Harper says, “Yes, Black women should have the vote, but really where we should be aiming is for human rights, for a set of principles, for a political movement that will not only speak to us, but will speak to the many generations forward.” This, again, becomes part of the defining feature of the women in Vanguard. They kept using the term, I kept encountering the term, “humanity.” What do they mean by that exactly? Is it just a turn of phrase? But no, it’s a political philosophy. It’s a lonely one in the sense that they don’t win immediate allies. But they set the bar high, and establish a set of principles for themselves that I think we could still say we are still striving for, some of us, even in the 21st century. It is really visionary, that far back during the early years of Reconstruction. Kaler-Jones: That’s so powerful, the questions that you share of what is freedom, what is citizenship, that they were grappling with and navigating. One of the overarching themes in the book is you talk about how the women of Vanguard were really situating themselves in humanity. What is humanity, and how do we ensure the rights of all? You write in your book, “suffrage alone was too narrow a goal for Black women.” As they are wrestling with freedom and citizenship, they also were wrestling with what you talk about as mobility, because one of the things that really struck me is in many instances of transportation resistance, of being able to have the rights to freely move about the country. So could you talk about Black women’s transportation resistance? Then, what are some of the other rights that Black women organized for? Because, as you say, suffrage alone was too narrow a goal for Black women. Jones: Really, too narrow a goal, and one of the questions that I think students and historians alike have asked for a long time is ,”Why aren’t more Black women part of the so-called mainstream women’s suffrage associations? Why aren’t they there? And for our sake, for too long — really until the work of Dr. Rosalyn Terborg-Penn starting in the 1970s, too long — the view was that Black women weren’t interested in political rights. That they were prepared to cede the political sphere to men, in some gesture of, I don’t know, heteronormative conventional family thinking. Well, not so fast. When we follow Black women, what we find is that they are establishing organizations like the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs. Why? Because the suffrage associations are not only refusing to take up what we’ve called today an antiracist agenda, they are, in fact, trading in anti-Black racism in an effort to win the 19th Amendment. So, Black women need a space that is separate and distinct from that movement. But to your point, they need to be able to work simultaneously on, yes, winning political rights, but also winning anti-lynching legislation. The great Ida B. Wells is going to be among one of the great Black suffragists at the end of the 19th and into the early 20th century. We remember her well, as importantly and necessarily, for her anti-lynching work, but she was as powerful a suffragist, and this is the kind of breadth that Black women need. Now, when it comes to mobility and transportation, what Black women understand is if you can’t get to the polls without being accosted on the streetcar, if you can’t get on the train to head across the state to attend the political convention, voting rights mean nothing. And so, again and again, in a harrowing rite of passage, nearly every woman in this book at some point relates that moment when she is accosted by a conductor, a brakeman, a ticket taker, a constable, and more. And here, I want to point out, one of the things I learned is that all of this happens in a moment when Black middle class women in particular are practicing something that we termed the politics of respectability. What I learned here is that even women who practice the politics of respectability are prepared to throw down with a man who puts his hands on her and looks to eject her from her, Ida B. Wells is a case in point. So, we really learn about the deep and broad sensibilities of Black women’s politics through these confrontations. As historian Mia Bay has explained in her recent book, Traveling Black, this is not a sidebar story. Bay has argued, I think, really persuasively that the struggle over mobility is the foundation of the Black Freedom Movement. That there is no movement, right? We can’t understand it. In fact, we don’t understand the context over getting to the polls, getting to the school house, getting to the meeting place. We can’t understand those things if we don’t understand how hard it was to actually get there. Kaler-Jones: Wow. As we think about mobility, and what you name about how oftentimes corporate textbooks confined Black women, saying that they can only be about one issue or one thing — you name Ida B. Wells, who is known for anti-lynching campaigns, but was [also] incredible suffragists. Then I think about the larger themes that we’ve been discussing in this course, or in this series of courses, thinking about Jeanne Theoharis’s work on Rosa Parks and expanding our ideas of, as Jeanne says, not just confining Rosa Parks to the bus, but also talking about her longtime activism, her longtime strategic organizing around so many other issues. That brings me back to another key theme of this conversation of finding Black women where they are, and one of the things that I love about this book is that there are so many teachers highlighted throughout. You name Maria Miller Stewart, Sarah Mapps Douglass, Charlotte Hawkins Brown, Charlotte Forten [Grimké], Anna Julia [Haywood] Cooper, and Susan Paul, who you said in quotes, “transformed her school room into a platform for anti-slavery work.” So, can you tell us more about how Black women educators used classrooms to mobilize young people and the struggle for equality and freedom for all? Because it’s not just about one issue, right? It’s about so many of them coming together. Jones: Yeah, thank you for that. I just want to say, as an important aside, how indebted I am to the work of Dr. Theoharis on Rosa Parks. While I know not everyone reads the footnotes all the time, my footnotes in this book really are a tribute to the many, many historians who have done just remarkable labor around recovering the history of Black women’s politics. So this book stands on the shoulders of historians like Dr. Theoharis and many, many others. So please discover them and read them also because I couldn’t have written this book without them. But your question is, I guess, a really important one for me. And how do I want to put it . . . When I began this book, I had a lot of questions, and dots that I hadn’t really connected. One of them was how important educators were, teachers were here. So you’re right, from the early chapters and a figure like Susan Paul, who in Boston, in the midst of the radical anti-slavery activism of the 1830s, is going to organize her students to tour, to entertain, and to raise money for the American anti-slavery society. What an education, right? Imagine that as a young person. Already probably what’s going on in your classroom is pretty remarkable if Susan Paul is your teacher, but then she takes you on the road? And you are meeting luminaries, you are attending meetings. They are refused travel while they are touring, and so there’s no substitute really, for this kind of experience. I became fascinated by Washington, D.C.’s fabled M Street [High] School, a place where Mary Church Terrell, among others, [and] Anna Julia [Haywood] Cooper, [taught]. If I say that to you, and you imagine you arrive in high school, and there is Mary Church Terrell. What’s going on there? Well, what’s going on there is that they are producing young people with stellar education. But they are educating young people for their own time, for their own challenges, for their own activism. And this, I think, is an essential part of the story, as I understand it for the women of Vanguard, is a keen appreciation for how their struggle is a struggle across generations. And it is not possible simply to imagine, as ambitious and as committed as you may be, that you will get all of the work done. So we watch these women educators again and again investing in the next generations of young women and men. Importantly — and this, I think, is the key to the longevity, to the continuity, to the power of Black women’s politics — is never seeing the question as settled in an election cycle of all things, which is just a flash in time, but really investing in the long struggle. Kaler-Jones: I appreciate you naming the intergenerational aspect of this work and how critical it is in the continued struggle. As you were sharing I was thinking about one of our previous conversations with Jarvis Givens on Fugitive Pedagogy and the story that he tells about Tessie McGee, a 20 year old Black educator who had Carter G. Woodson’s textbook in her lap, engaging in this very subversive act, and then going back to the corporate textbook when the authorities came in. So, I’m just in awe of the number of Black women educators in history, and also that are in the virtual space with us today, that ground and guide us towards the North Star, which really gets us back at the humanity, at the struggle for equality and justice for all, what we were promised but are still actively fighting for. The book gives us such a rich history and a call to action to carry out the lessons from the Black women of Vanguard. You write, “the story of Vanguard is still being written.” That to me is very much a call to action. So, what should educators teach about the long history of the ongoing struggle for voting rights amid a failed voting rights legislation at the federal level, a Supreme Court that upheld voter suppression, and continued attacks to teaching the truth about history that shapes voter suppression, what lessons can we continue to learn from the Black women of Vanguard? Jones: I think that, importantly, the women of Vanguard are nimble, which is to say they develop the capacity to read a political moment and to respond to it, and be in it in real time. Sometimes that means working in more than one strategy at a time. But I think one of the things that binds many of them together is, on the one hand, there’s no substitute for the work in the trenches. There’s no substitute for that, right? There’s no way around, in American politics, the boots, the sleeves rolled up, in every cycle doing the work. And I see the women in this book doing that season in and season out. However, when they have the microphone, when they have the pen, when they have the opportunity, they are visionaries. They are not wholly subsumed by the muck in the trenches. And when the question is put, they are women who will speak to you about human rights, about dignity, about democracy, and really, always reminding us where the bar is put. I think that in the 21st century, if I could say where it can feel like politics is reduced, either to sort of rhetoric and talk, or is just stuck in the muck of the trenches. This model, this understanding that part of our challenge is to be versatile enough to do both. I think that’s actually what sustains many of the women in this story — they hear the visionaries in their midst and they become their own visionaries for their own time. And I think this is profoundly sustaining. I would say that women in this book do what they do, in part, because they know they’re right. They know they’re right. That doesn’t mean they carry the day all the time. It doesn’t mean that everyone comes on board and concurs. But there’s something very powerful about a politics in which you actually have arrived somewhere with a vision that you can commit to, and you can use to animate your own work and to animate your entire community, your entire movement. So this, to me, is important to say, along with the intergenerational piece, that is, if we are impatient about politics — as we should be impatient — at the same time, for me, there’s a piece of the story which is about understanding that American democracy has been defined from its inception by struggle over the very questions that animate the women in this book, that animate us in our own lives in the 21st century. That means we should anticipate that even as this battle might be won, might be resolved, there will be another challenge to our values, to our vision of human rights and more. But that is the kind of democracy this is. I don’t believe where we’re headed is to the perfect union. I think what we are is the sort of democracy that is going to expend itself ultimately on struggles over some very fundamental principles, and voting rights is one of those principles. Kaler-Jones: Wow, I’m going to be thinking about that for a while, particularly when you said they know that they’re right. It makes me think about Monique Morris, in her book Sing a Rhythm, Dance a Blues talks about Black women, blues women, and she says, “they know what they know and they know that they know it.” The vision is so clear to them, and they continue to be in pursuit of it despite the pushback, despite the backlash, despite what has been so deeply rooted in anti-Black racism and heteropatriarchal sexism, and all forms of oppression. So I appreciate you naming that and pointing us back to really the vision that the women of Vanguard offer us, and really passing the torch and continuing to light the way forward for what is possible when we all work together in the continued struggle. So thanks, everyone, I hope that you had robust conversations in your breakout rooms, please share what you talked about in the chat box and also drop your questions in the chat box. We really want to hear from you as we continue on in this conversation. What would you like to know from Dr. Jones? What are the questions that are on your heart and mind that you would like to share? Please do drop it in the chat box, and if you could put it in all caps for me, that would be so helpful. So now that we are back, Dr. Jones, I’m going to jump back into some of the questions that we have as we wait for some more questions to populate in the chat. One thing — there are so many things that were so fascinating about the book — but one aspect of the book that I really want to highlight is your discussion on how Black working women maneuver their own routes to power, which was illustrated by the Zephyr Wright’s story. So, can you tell us her story and share some examples of how Black working women created their own routes to power? Jones: Thank you for naming Zephyr Wright, who was someone I didn’t know before I encountered her photograph — one of three Black women photographed during the signing of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. She’s standing alongside Vivian Malone and Patricia Roberts Harris. But this photograph, initially, I didn’t know who any of these women were and I realized it was a photograph that was reproduced quite frequently. The captions always named the men in the photograph; there’s Martin King and Ralph Abernathy, [and] of course there’s President Johnson. But not the women. I actually began my journey to understanding her better by crowdsourcing the photograph on social media, and amazing things happened. Like I met Vivian Malone’s sister, Sharon Malone, on Facebook, and she said that was my sister and she narrated the photograph for me. It was extraordinary, which is a tribute to how we are carrying these stories or parts of these stories with us frequently. And how curious that social media becomes the place where sometimes we come together and we share the stories. But there we were, and it was very meaningful. But here’s a woman who works in the home of Lyndon Johnson’s family in Texas, and when Johnson takes the White House, comes to Washington to work there. She’s the family’s personal cook. But what we learned when we probed and we asked what is she doing at the signing of the Voting Rights Act exactly, we discover that she is someone who has used her position in the Johnson household to present herself as an advisor to Johnson, particularly on civil rights issues. And she is credited, in many ways, with giving lived meaning to the scourge of Jim Crow to Lyndon Johnson. When, for example, she explains to him that she can’t drive with the Johnson girls up from Texas to Washington because there are no accommodations for her. Tragically, this is an education for Johnson, but it’s an education nonetheless. So, I think that there are so many moments in the book where we watch women make more of what was intended, for where they land, from where they sit, from where they stand, from where they labor. And she’s a really vivid example of that. And the pictures in the book — I hope folks will see it because she’s quite elegant. And clearly actually very much at home it seems in this rather formal and kind of raucous signing scene. It’s another example for me of what it means to do Black women’s history, which is to train your eye to find Black women where they are, to follow them where they are. When you see them ask the questions, “Who is she? What is she doing here? What does she stand for? What stories did she open up?” I was surprised, in her example, that even at the Johnson archives — where the original of this photograph resides — in the formal archival record she wasn’t named. So that is part of our work, is sort of restoring those names, those identities, those people, those stories to the record for many more of us. Kaler-Jones: Wow. I love that story so much, and I did not know that you went on social media too, with the photo to try and find . . . Jones: It was kind of fascinating. I got a lot of wrong advice too. That’s important to say: I got a lot of people who just miscalculated who was in the photo. Sharon Malone came on. I said, “Okay, now I’m here right where I need to be.” It was very powerful, because of course social media is one of those places — I don’t know about other folks — where I feel like I’m at my best there. When I’m an educator, I hate when I’m trying to use the platform and the space to teach — you know, a lot goes on. We all know that it’s not all where you want to be. But in a moment like that, when you can in real time be teaching yourself, but also other folks, about history — those are some of my favorite moments on social media. Kaler-Jones: That’s incredible. I’ve seen so many young people leverage social media to share such rich information. Also educators that have been using social media to build community across the country. I love following the Twitter threads that I see always being highlighted on the ZEP [Zinn Education Project] Twitter. What a powerful testimony to coming together in a virtual space. I want to turn to the chat box here and lift up a question from the incredible Miss Judy Richardson, SNCC organizer. Miss Richardson asks, “In the modern Civil Rights Movement, local women protected us SNCC and other voting rights workers, folks like Mama Dolly [Raines] in southwest Georgia, Mrs. McGhee in the Delta, too many to name. So, do you find this kind of self-defense through time?” Oh, there’s Judy! Good to see you. Jones: So, first of all, what an honor to have you with us. And thank you for your question. I think one of the challenges in a book like this is that I’m not able to name everyone who should be named — and folks come to stand in for a much more complex whole. That’s important to say. But I think you couldn’t tell this story if you don’t understand that, first of all, Black women built a new movement for voting rights out of the disappointments of the 19th Amendment. And that takes 45 years, and yes, you can tell that story through the NAACP and its litigation strategy, and you can tell that through Black women suffragists and those who become Republican Party operatives. But what we know is that ultimately, a transformation like the Voting Rights Act is only going to happen when thousands and tens of thousands of Black women hold the feet of this nation right to the fire of Black voting rights — and that is the feet of the political parties, that is the feet of Congress, that is the feet of Lyndon Johnson. It’s impossible to understand the story. If we don’t understand that, it’s impossible to understand how in the 21st century Black women are still doing that work of safeguarding one another on election day. It was true, and Mary McLeod Bethune’s time in 1920 in Daytona, Florida, when the Ku Klux Klan marched on Mrs. Bethune’s school, [which] today is Bethune-Cookman University. It was Mrs. Bethune, it was her teachers, who stood up to the Klan in the middle of the night and then gathered up Black women the next morning and got them to the polls. Well, we’re still doing that work, aren’t we? And we’re going to be called on to do that work increasingly so in the face of emboldened voter suppression. So for me, I guess there’s a regret I have to express in response to your question, which is: I have not named all of those women here, but I hope that their presence and their power and their purpose come through in some of the stories that we tell. Thank you so much. It’s really, what an honor. Thank you. Kaler-Jones: Wow. I’m just so grateful for that question, Miss Richardson, and continuing to point us back to the powerful everyday Black women who have always, and will always, continue to lead us in the struggle. I’m going to turn back to the chat again, because we have another great question from Ben Williams. Ben asks, “When you think of the empowering stories of joy amidst the struggle, what individual story comes to mind that you’d like to lift up?” I love this question. Jones: I do too. And I have to say that I hope it’s not too obvious that I’m going to reach for the indomitable Ida B. Wells. I first met Ida B. Wells through the work of many great scholars. But, when I used to teach her, I began to put together a collection of photographs. She’s photographed frequently, very self consciously, and deliberately. And my students began to remark, I think, on her dress. Ida B. Wells had an extraordinary fashion sense, and I can only think [she] took a great pleasure in those outfits, in composing those portraits, in sitting for them, [and] distributing them. I think that it’s a quality we might overlook, because they’re old and tiny, right? But for me, by the 20th century, there’s this increasing capacity and this increasing awareness about crafting one’s own image for one’s own pleasure, one’s own sense of beauty, of style, and more. And the portraits are really extraordinary. I wrote a small piece on a woman named Hallie Quinn Brown, who was president of the National Association of Colored Women’s clubs in 1920. When the 19th Amendment is ratified, Hallie Quinn Brown gathers the Black women in the NACW and launches their campaign for federal voting rights legislation, [which] takes a long time, 45 years. But, as I was writing I wound up in an exhibition in the Library of Congress, and there was a portrait of a young Hallie Quinn Brown, and she was styled to the nines. You just had to think, amidst an educator, a church activist, a suffragist on the front lines of troubled work, but these are women who are crafting their own image and are fashioning it, I have to just believe, right for themselves and for one another, in a way that we can at least glimpse and I think very much appreciate. Because I don’t think that tradition has left us; I think there’s still a great deal in our self-fashioning that is profoundly expressive of a kind of politics. Kaler-Jones: I love, love, love that. It makes me think about using more photographs in our teaching. I’m thinking about, as an example, Karen Lee, who I know is on the call as well, and we co-teach a youth organizing fellowship here in Washington, D.C., and we did a lesson where we posted photos of Black organizers and activists throughout history up through the present day doing joyful things. So, it was Rosa Parks doing yoga; it was Fannie Lou Hamer just laughing; and we had such a robust conversation about why we don’t see these photos of joy in classrooms — well not in classrooms, but rather in textbooks — why those photos are oftentimes not highlighted. So I love that you continue to point us to meeting Black women where they are. Sometimes that means looking into the photographs and looking to those moments of joy and being reminded of the necessary components that make us human, as Black women point us back to humanity. And part of that is so deeply rooted in joy, so I love that. And thank you for that question, Ben. Another question that I have is, shifting gears a little bit, the press is another theme throughout the book. You talk about The Herald, The Liberator, and more. So, what was the role of the press in Black women’s narrative? As we’re talking about Black women, fashioning themselves and writing their own stories, what was the role of the press in Black women’s narrative and political power building? And one of my favorite lines that you write, under Jarena Lee’s commissioned portrait, you said, “In her right hand, Lee holds a quill, a reminder that she is the author of her own text, a woman accustomed to handling fine writing instruments and firing off those ideas they produce.” So, I would love to hear a little bit more about the role of the press in Black women’s narrative and political power building. Jones: Yeah, thank you. Phillis Wheatley with the quill. Jarena Lee with the quill. This is a symbol, not only of a capacity, but of a kind of power that comes to them by virtue of that capacity. And they understand that. They highlight that. They under underscore that for us. Early in this book, much of the press is important because there are men like William Lloyd Garrison, the abolitionist who was an ally to Black women activists, be they in Philadelphia, in Boston, in New York, who have access to the pages of The Liberator, and really break into politics and develop their voices on the pages of that anti-slavery newspaper. But by the 1850s, we’ve got the extraordinary Mary Ann Shadd Cary, another educator and activist, a refugee who has landed in Canada and who is going to found her own newspaper, now this is next level, publishing her own newspaper, the Provincial Freeman. And she is not only a writer, she is a curator. So she is steering the course of Black political thought through her own ideas, but also through the curation of the ideas of others. It is a very, very powerful instrument. It wins her friends, and it wins her enemies. And in fact, she spends the early years editing the paper clandestinely because she understands the kind of fire she’s going to attract as a woman newspaper editor. So, I think we can’t underestimate the ways in which the pen, the published word, that capacity, is part of this story. I’m thinking about Anna Julia Cooper, by 1892 publishing her Black feminist manifesto, A Voice From the South. Now she’s going to full-throatedly sort of gather what Black women have been arguing and pressing and claiming for decades into this text. That is a wonderful teaching opportunity because there is so much in it. So I think that here we are in the 21st century — and maybe I’m just too hackneyed to tell young people that actually the newspaper was the Twitter of the day and all that — but we can see it, I think we can make those arguments. It’s really fascinating, for me, to take a part of paper like the Provincial Freeman, and see how Shadd Cary is borrowing and pulling (and retweeting, if you will) to really sharpen debate, and to illuminate the questions of the day. She’s a great promoter of Black women activists. And it really matters — it really matters the work that she does there in Canada west in the 1850s. Kaler-Jones: Wow. As we’re talking about using some of these items as teaching tools, or even thinking about primary and secondary documents and research, and finding these stories, there’s a question in the chat box from I believe, Anita, who asks, “In all of your research, what shocked you the most? Something that you thought you knew, but something that maybe came up that changed your mind?” Jones: Gosh, I think that’s a great question. So, I’ll tell you something that happened to me on the way to finishing this book, and it was that I became very self conscious that I didn’t know much of anything about how the women in my own family fit into this story. I knew some stories about my elders; I even knew them as activists, some of them. But no one had ever talked about how they fit into the story of voting rights. So the first shock, if I could put it that way, was when I go to the state archives in North Carolina, I’m looking for the records of Black women’s votes — perhaps in the 1920s, perhaps later — and I discovered that none of the records have been preserved. That’s almost like the inverse of the question, right? But I have this burning question. I’ve come all the way to Raleigh to discover the answer and there’s nothing there. Now, whether those records disappeared by design or by neglect, I can’t say. But what I do know is that in those early years of women’s votes in North Carolina, no one preserved those records, no one cared about them, no one anticipated, no one maybe even imagined, that we would be writing this history, that we would be telling these stories; that we would be showing up at the State Archives and saying, “Now we want to know, when did Black women vote?” And so partly, I’m looking for the women in my own family and my own grandmother. Here’s the kicker: This happens way after the book is published. I have a sister, a wonderful sister, who writes to me and says, “I’ve been holding on to these old family papers. That’s not really my thing; you seem to be the one. So, I’m going to send you this box.” And it’s sitting right over here in my office. She sent me the box, and it’s just a hodgepodge of things that she’s held onto. How she got them, I don’t even know. Among them is my grandmother’s voting certificate from, I think, 1953, in Greensboro, North Carolina. It had been there all the time. But even in our family we hadn’t quite seen it. So, I guess I want to say that for me, working on the book gave me a different set of expectations. Maybe it was partly a close encounter with the women in my own family that really sharpened that for me. That’s a great question though, thank you. Kaler-Jones: I actually would love to ask the final question for this evening, about what you were just talking about — your own family. Can you share how you started writing Vanguard by collecting stories from the different women in your family? I think I may have heard in another interview that I was watching of yours that your editor may or may not have known that that’s what you were doing? So, we’d love to have you share that story with the group. Jones: Partly, the story of this book is that I get the urge to write it kind of in a fury because I realized, in 2020, we were going to mark the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, and signs were that some folks were just going to forget or set aside Black women and their story. So, I’m under some time pressure to get this book finished, which is why I don’t tell my editor that I’m taking this detour to do the family research in Raleigh. But I really learned something by doing it that I think he ultimately appreciated, which was that I didn’t find my grandmother in the state archives, and my sister had this paper tucked away so I didn’t see it until much later. But I did ultimately come across an interview that she had given in the 1970s. A historian at Duke University, Bill Chafe, is writing a book about the history of civil rights in my grandmother’s adopted home city of Greensboro, North Carolina. My grandmother spent her life on the campus of a historically Black college, Bennett College for Women, in Greensboro. In the interview, Chafe asked her about voting rights. So I’m like, “Wow, this is my mom. This is what I’ve been searching for.” But what was remarkable is that she didn’t speak about 1920, though she was a young woman of voting age in 1920. She lived in St. Louis, Missouri for a time. She doesn’t speak about those years at all. She talks about the 1950s, and about the young women students at Bennett who are part of Operation Doorknock. And she talks about how thrilling it is to be with them as they are now going door-to-door and getting Black folks in Greensboro registered, [and] getting them to the polls. This is the lesson that I needed to learn, which is that if I stopped this book in 1920, I miss my grandmother, I miss all the women like her for whom the story of voting rights, the thrill of voting rights, the moment when they’re queried they go to is not 1920 at all — it is the 1950s and the 1960s and the modern civil rights struggle. So this to me was personally very moving, but it was also really one more lesson in why we need to listen to Black women and hear their testimony and think about our work differently through it, because this book had to come to 1965 and beyond to do justice to her story and so many other stories. Kaler-Jones: Thank you for that. Thank you so much for sharing these stories that are in your own family. Now I’m feeling inspired to go back and see what I can find as well. And I think, as I’m beginning to close out the conversation again, I’ll end just as I started and say that we probably could be in conversation with you for hours and there would still be so many stories to tell, just as Miss Richardson pointed us to. I’m just reminded of the continued struggle, I’m reminded of the beautiful and powerful vision of Black women pointing us always, always back to humanity. And grappling today with these difficult questions of what is freedom? What is citizenship? What does that look like? What does that feel like? And I know that we have much work to do, but you have reminded me that we are all part of a long, strong, rich legacy. As you say in your book, Vanguard is still being written. So, I feel that and I take it very much as a call-to-action for the work that’s to come and the work that’s ahead. Thank you so, so much for being in conversation with me and the Zinn Education Project. Thank you to everyone here who has taken time out of their day to be here and to learn and to engage in dialogue and discussion. The chat box is always going off in these classes! I’m so honored to be a part of this community of folks committed to a future that is rooted in justice. While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Transcript

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the lessons, books, articles, and more recommended by the presenters and also by participants.

Lessons and Curricula

|

Seneca Falls, 1848: Women Organize for Equality by Bill Bigelow When the Impossible Suddenly Became Possible: A Reconstruction Mixer by Adam Sanchez and Nqobile Mthethwa Who Gets to Vote? Teaching About the Struggle for Voting Rights in the United States by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca |

Books, Articles, and Archives

|

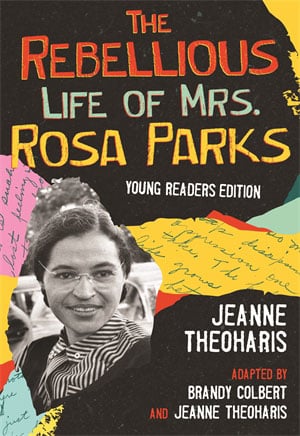

In addition to Martha Jones’ Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All, the following books were referenced. Traveling Black: A Story of Race and Resistance by Mia Bay (Belknap Press) The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks: Young Readers Edition by Jeanne Theoharis and Brandy Colbert (Beacon Press) Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880-1920 by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham (Harvard University Press) Persistence: Evelyn Butts and the African American Quest for Full Citizenship and Self-Determination by Kenneth Cooper Alexander (Orange Frazer Press) Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina, and the Black Struggle for Freedom by William Henry Chafe (Oxford University Press, USA) Hallie Quinn Brown (National Park Service article) The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Digital Gateway offer interviews, essays, and primary documents. |

This Day In History

Participant Reflections

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

I’m reflecting a lot about the story Dr. Jones shared about the woman who was LBJ’s chef (need to go back and look up her name). I think it’s incredibly powerful that she used her influence, her expertise to wield her power and to make history. I think allowing women to be authentically themselves resonates with young people today. I’m moved that young people do not always place each other into boxes and I think this story is incredibly illustrative of that idea.

I was inspired by the story of the search for the identity of the woman in the photo of the signing of the Civil Rights Act. Also hearing Judy Richardson’s acknowledgement of the women who offered protection, and about Martha Jones learning of how the women in her family fit into the larger story.

That great change comes about by individual small actions whether recorded in official record or not.

Everyday Black women have always been and will always be at the forefront of the Black Freedom Struggle — and I love the phrase describing being nimble — “developing the capacity to be in a political moment and respond to it in real time.”

Learning about how “the struggle for mobility was the foundation of the Black women’s struggle for freedom.” I never thought of the violence inflicted on Black women to prevent them from exercising their right to vote, their political rights, their HUMAN rights!

The everyday lives of Black women who made a difference, even the ones we’ve heard of in history class like Ida B Wells, are barely developed as powerful figures who made a world of difference.

The conversational tone of Dr Jones wanting us to know these stories — and the wonderful way Cierra encouraged that level of sharing and communication.

The determination that Black women had in face of obstacles and real violence that they experienced. They knew the risks and forged ahead anyway.

Everyone has a story — be encouraged to learn it and share it to be an inspiration for others. Together, we WIN!

What will you do with what you learned?

Add more historical literature and stories of Black joy, empowerment and liberation to my course on diversity. As is, the course centers oppression, violence and struggle related to race, gender, and sexual identities. As a Black female professor, I often find that the master narrative is all my students of color know and sadly believe about themselves and their histories. Being able to provide them with names and resources will be one of the most effective ways of disrupting deficit thinking and frankly noticeable self-hate.

My students do several short research projects throughout the year focusing on underrepresented voices in the curriculum particularly women and people of color. The names and other information from this session will be included but also the resources and the suggestion to “find them where they are” will guide my own research as well as that of my students.

I am a literacy tutor, and I will start introducing these women into my student’s literacy texts. Which also brings another element that Miss Cierra brought up about using photos of Black women as teaching tools — images of joy.

I am excited to delve deeper into the connection between anti-literacy laws, literacy tests for voting, and current miseducation in literacy at the elementary level. I will use this as fuel for teaching the science of reading in my school and sharing what I learn with teachers and students.

I will try to incorporate numerous ideas regarding the role of Black women in Reconstruction, voting, protecting each other, transportation resistance, etc.

Continue to use herstories to empower students to meet the challenges they’re facing today.

Additional comments

Thank you so much for your scholarship. Learning about the women who fought for voting and civil rights will help our students to understand it was not just men doing this work. So glad we have scholarship that takes us beyond the regulation textbook for our students to learn the diversity of the struggle. Thank you for sharing your family story as well. I feel it is those personal stories that we share that make the history more real for our students.

I am very happy that I chose tonight’s session with Dr. Jones. I’ve been searching for ways to improve my knowledge for my professional practice, but this session exceeded my expectations because it was a personal blessing. Just knowing more about the dynamic legacy of Black women in US history, revealed, uncovered, made visible to Black women like me.

Dr. Jones, thank you for emphasizing the intergenerational struggle to attain voting rights and the message that we must be versatile and prepared to continue to meet the new challenges we will continue to encounter on our journey for civil rights.

Thank you for this enlightening work on the role Black women have played in voting rights. It inspired me to learn about Puerto Rican women who have been instrumental in the work of activism.

Presenters

Martha S. Jones is the Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor and professor of history at The Johns Hopkins University. Her books include Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All and Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America

Cierra Kaler-Jones is a social justice educator, writer, and researcher based in Washington, D.C. Her research explores how Black girls use arts-based practices as mechanisms for identity construction and resistance. She is the director of storytelling at the Communities for Just Schools Fund.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn