Quotes about the Reconstruction era and why it should be taught. Most of the contemporary scholars of U.S. history, who are quoted below, also signed the Open Letter to School Districts on the Need to Teach the Reconstruction Era.

W. E. B. Du Bois

Nations reel and stagger on their way; they make hideous mistakes; they commit frightful wrongs; they do great and beautiful things. And shall we not best guide humanity by telling the truth about all this, so far as the truth is ascertainable? — W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 1935

One is astonished in the study of history at the recurrence of the idea that evil must be forgotten, distorted, skimmed over. The difficulty, of course, with this philosophy is that history loses its value as an incentive and example; it paints perfect men and noble nations, but it does not tell the truth.” — W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 1935

Daily the Negro is coming more and more to look upon law and justice, not as protecting safeguards, but as sources of humiliation and oppression. The laws are made by men who have little interest in him; they are executed by men who have absolutely no motive for treating the black people with courtesy or consideration; and, finally, the accused law-breaker is tried, not by his peers, but too often by men who would rather punish ten innocent Negroes than let one guilty one escape. — W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk, 1903

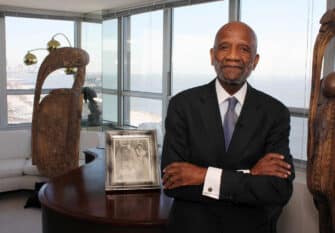

Lerone Bennett Jr.

Reconstruction in all its various forms was a supreme lesson for America, the right reading of which might still mark a turning point in our history. As a matter of fact, an understanding of the triumphs and failures of this first Reconstruction is indispensable for an understanding of the triumphs and failures of the second Reconstruction we are now undergoing. — Lerone Bennett, Black Power U.S.A.: The Human Side of Reconstruction, 1867-1877

Over a century ago, prodded by the demands of four million men and women just emerging from slavery, Americans made their first attempt to live up to the noble professions of their political creed — something few societies have ever done. The effort produced a sweeping redefinition of the nation’s public life and a violent reaction that ultimately destroyed much, but by no means all, of what had been accomplished. From the enforcement of the rights of citizens to the stubborn problems of economic and racial justice, the issues central to Reconstruction are as old as the American republic, and as contemporary as the inequalities that still afflict our society. ― Eric Foner, professor emeritus, Columbia University in New York Times

More than most historical subjects, how we think about this [Reconstruction] era truly matters, for it forces us to think about what kind of society we wish America to be. ― Eric Foner, professor emeritus, Columbia University, in New York Times

Reconstruction is the lens through which we have to view the rest of American history. — Greg Carr, associate professor, Howard University

Hilary Green

As the events of January 6, 2021 has shown, the lack of critical teaching of Reconstruction era, including the three constitutional amendments, biracial governance, African American political citizenship, and violent overthrow, has had a consequence of recent political debates. Reconstruction is essential for not only understanding the creation of the modern United States but how the unreconciled legacies from emancipation and Confederate defeat shapes the present. — Hilary Green, associate professor, University of Alabama

We gain so much by studying the Reconstruction period. We simultaneously come to know the possibilities of a better society and the lengths that the opponents of such progress will go to violently subvert it. It is one of the most important eras in U.S. history for providing the historical context of our current moment. We do a great disservice to students by ignoring its importance. — Tyler D. Parry, assistant professor, University of Nevada

If students don’t understand Reconstruction, they don’t understand U.S. history, politics, or form of government, nor do they understand the history of racism and racial oppression in the country. No period in U.S. history is more important for the nation’s story nor more relevant to the students’ experiences today. — Gregory P. Downs, professor at the University of California at Davis

Reconstruction is the first time when American political leaders really tried to create a multiracial democracy. Such a thing was not attempted back at the time of the American founding. — Kate Masur, associate professor, Northwestern University (Quote from Reconstruction 101: Progress and Backlash, Hard History Podcast)

Too often in our schools, movies, and televisions, white supremacist mob violence, when it is acknowledged at all, is contextualized as exceptional or unusual, a departure from what is ‘normal’ or truly ‘American.’ During postwar Reconstruction, violence by white mobs and paramilitary terrorist organizations was legion. These mobs particularly targeted Black lawmakers, Black voters and their allies.” — Joshua D. Rothman, University of Alabama, Hechinger Report

You cannot understand the United States without studying Reconstruction. Learning this vital history helps all of us reckon more honestly with the realities of our country — its promises and possibilities as well as pitfalls and prejudices — that can move us beyond stubborn myths and superficial celebrations. — Timothy Patrick McCarthy, Harvard University

I still encounter students who’ve only ever been taught in K12 settings the lie that Reconstruction was a “corrupt” northern effort to destroy the South. When Reconstruction isn’t simply minimized or ignored, so much of what is taught in K12 about Reconstruction pushes this falsified, mythical version of the era that was concocted to whitewash the Civil War era and justify Jim Crow. — Jonathan S. Jones, Virginia Military Institute

In so many ways, the central reference point for our time should be Reconstruction and how America’s first attempt at multiracial democracy was drowned in a mixture of white reactionary violence and ostensibly colorblind laws. — Thomas Zimmer, Georgetown University

The Reconstruction period was a momentous time in American politics and culture. As the nation tried to come back together after a bloody and traumatic war, the federal government tested the limits of its power to defend and protect the constitutional rights of American citizens. We are living with the consequences of these efforts — and ultimately, their abandonment — today. It is essential to teach and to study the Reconstruction period, therefore, to understand ourselves. — Megan Kate Nelson, author of Saving Yellowstone: Exploration and Preservation in Reconstruction America

James Loewen

Confederates saw Reconstruction as a problem precisely because it was succeeding. — James W. Loewen, Five Myths About Reconstruction

We still have not reached the level of interracial cooperation we attained during Reconstruction. . . The tragedy of Reconstruction is not that it failed, but that its successes were curtailed in 1877 and then reversed in 1890. — James W. Loewen, Five Myths About Reconstruction

This telling of Reconstruction’s history, one seen through the African American lens, is long overdue. The revolutionary changes to American democracy brought by the collective acts of Black people claiming and demanding full freedom resulted in a wave of political, social, and educational progress too long erased from our schoolbooks, unseen in our museums, unremembered in our historic sites, and misrepresented in popular culture. The real struggles, aspirations, and achievements of African Americans during Reconstruction were replaced by a host of mythologies focused on failure and bolstered by violence, stereotype, and institutionalized racism. Reconstruction and the long retrenchment following are deeply relevant to our lives today and demand to be reclaimed and understood as both a period and a process, in order to begin to make good those promises fashioned and then refused by the nation. — Candra Flanagan, Paul Gardullo, and Kathleen M. Kendrick in Make Good the Promises, Introduction

For far too long, the revisionist history surrounding and deflecting the brutality of Reconstruction’s overthrow by white Redeemers has framed Black liberation as a failed experiment, while simultaneously rehabilitating Southern secession as a noble and just cause. Echoes of this ideological defense of slavery and Reconstruction’s violent denouement can be heard in contemporary discourses, ranging from policing and mass incarceration to states’ rights and voter suppression. — Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in Make Good the Promises, pp. 84 – 85

Looking to Reconstruction is a reminder that spectacular acts of resistance like Bree Newsome’s climb or Rosa Park’s stance on the bus were not isolated incidents; they were not historical accidents in which the subjects of Black resistance were only episodically women. Although these moments capture the public imagination (Black and white alike), although they are embraced by the media and sometimes praised by political leaders, and although they are written about over and over again, these incidents are simply the tip of a long-submerged iceberg. If we look past the immediate spectacle of these moments, we see long histories and wide networks of Black women working behind the scenes: activists leading community organizations; orators inspiring everyday people; organizers offering aid and assistance door-to-door; volunteers filing paperwork to keep the lights on at headquarters. — Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in Make Good the Promises, p. 109

The reason why we don’t learn about Reconstruction or if we do we learn that, it was a failed experiment in multiracial democracy, is because Reconstruction condemns us. If you learn about Reconstruction, then you see, we didn’t have to become the country that we became for 400 years; that we have this brief period at the end of slavery, where we actually believed in multiracial democracy, where Black people began to govern, where Black people bring public education to the South. They bring progressive taxation, they began to create this progressive democracy that we believe that we were. — Nikole Hannah Jones, journalist, New York Times (quote from interview at Busboys and Poets)

Unfortunately, the transformative history of Reconstruction has been buried. First by a racist tale masquerading as history and now under a top-down narrative focused on white elites. It’s long overdue we unearth the groundswell of activity that brought down the slavers of the South and set a new standard for freedom we are still struggling to achieve today. — Rethinking Schools editors in Why We Should Teach Reconstruction

“My students weren’t caught off-guard [by Jan. 6],” — @DCPSSocStudies teacher Alysha Butler-Arnold.

Why? B/c they’d been studying Reconstruction era Colfax Massacre & SCOTUS rulings.

Read more by @valeriestrauss & @JoeHeim, here: https://t.co/LgcfLtb6kA #TeachReconstruction pic.twitter.com/Ki4BW5wYna

— Zinn Ed Project (@ZinnEdProject) January 19, 2021

The South knew it didn’t matter tht black ppl weren’t actually the reason Reconstruction failed if you create a unified claim that they were

— Clint Smith (@ClintSmithIII) February 19, 2017

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn