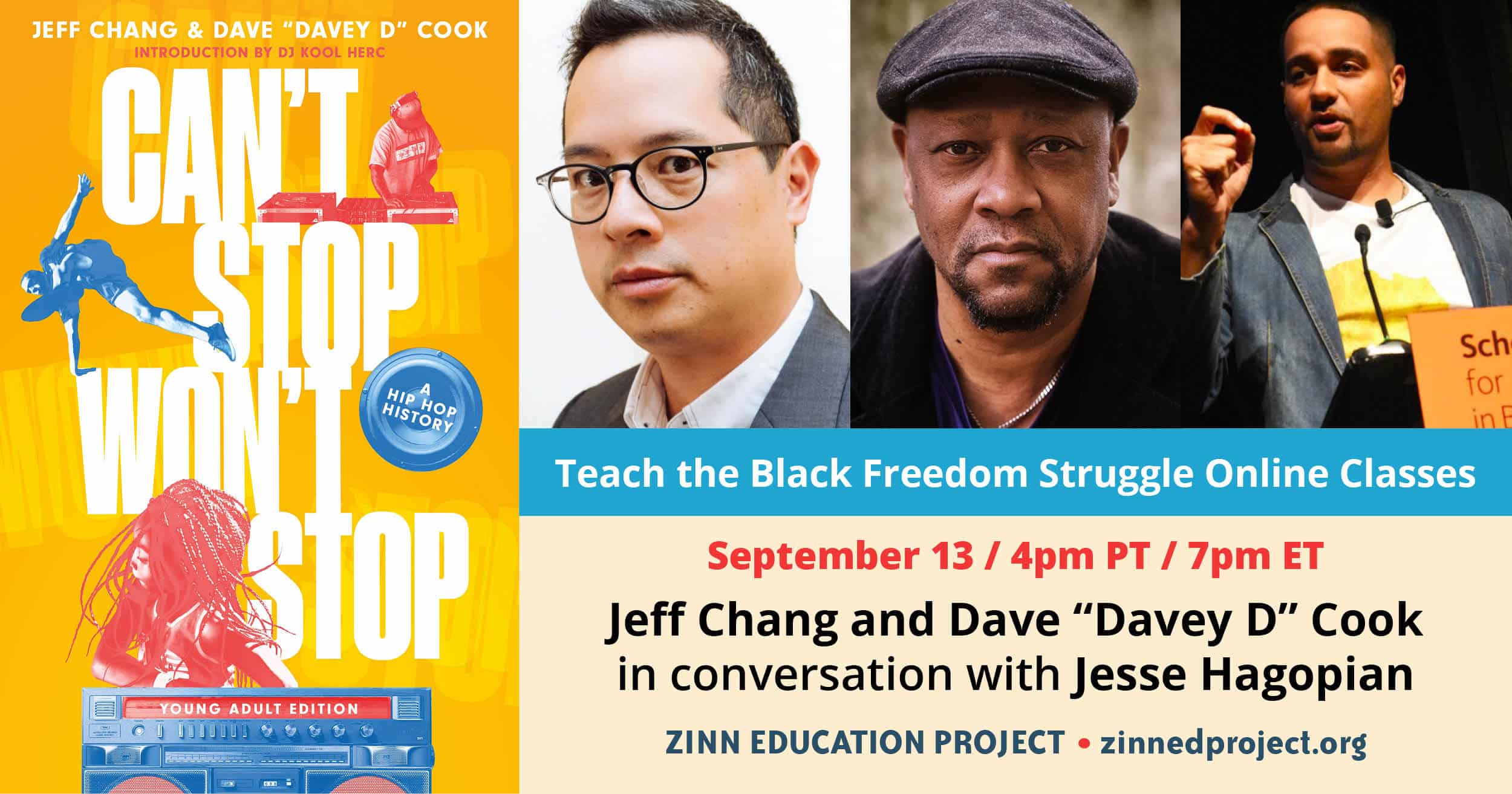

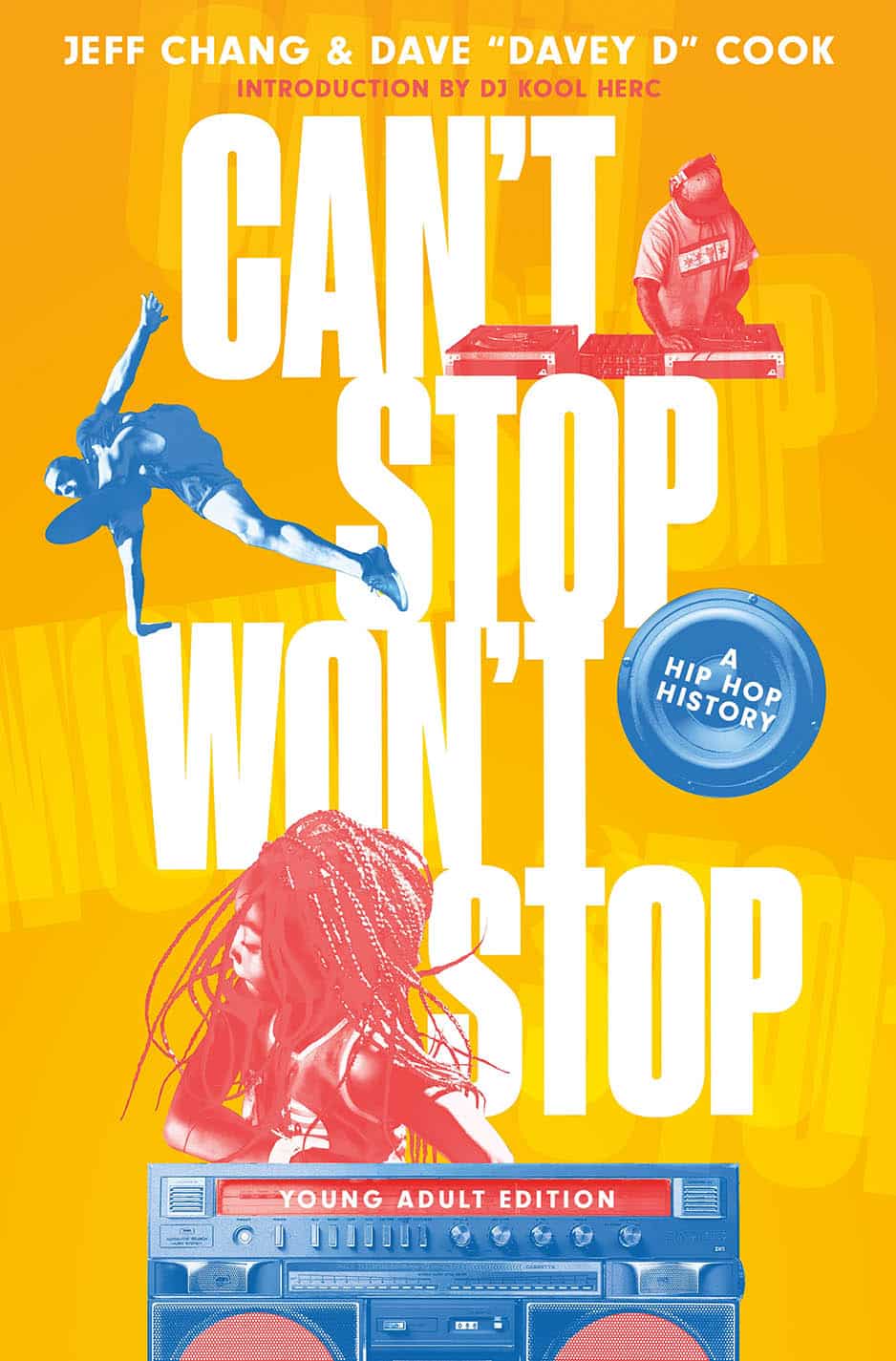

On September 13, 2021, co-authors Jeff Chang and Dave “Davey D” Cook were interviewed by Jesse Hagopian about their young adult edition of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A Hip-Hop History. This session was part of the Zinn Education Project’s Teach the Black Freedom Struggle online people’s history class series.

The young adult edition of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop is an essential guide for not only understanding hip-hop music and culture, but also a critical analysis of the last few decades of U.S. history.

The young adult edition of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop is an essential guide for not only understanding hip-hop music and culture, but also a critical analysis of the last few decades of U.S. history.

This seminal account of the music and culture situates the rebellion of hip-hop as a reaction to the neoliberal economic and social order that snuffed out the great social movements of the 1960s and 70s. Detailing hip-hop’s rise to global prominence — with attention to dynamics of race, class, gender — Chang and Davey D explain how young people — especially BIPOC youth — over generations have utilized the culture to express themselves and make their needs understood in a country that has abandoned and denigrated them.

Despite the importance to youth and its immense impact, in too many classrooms hip-hop gets excluded. This discussion was designed to help educators understand the history of hip-hop, the way hip-hop has shaped history, and how it can help make our classes more relevant to our students’ lives.

Here are a few reactions from the participants:

Davey D’s comments on the commodification of hip-hop are really resonating with me, and how it connects to taking the test as opposed to truly learning. I definitely want to go back and re-watch this session!!!

Everybody was so inspirational, and speaking to other educators across the nation was invaluable.

Loved the entire conversation and rethinking all of the ways to connect hip hop to such a wide variety of topics taught in U.S. and World History.

Hip-hop is a way for history to be told about the streets rather than the history that America wants us to know. This meeting was really inspiring.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion. Jesse Hagopian: We are very lucky to be joined by Jeff Chang and Dave “Davey D” Cook this evening. Jeff Chang has written extensively on culture, politics, arts, and music. His books include the adult edition of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop, Who We Be, and We Gon’ Be Alright. I recommend them all. And then we are joined by Davey D, a nationally recognized journalist, adjunct professor at San Francisco State, hip-hop historian, political commentator, syndicated talk show host, radio programmer, media justice and community activist. And they of course have put together the young adult version of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop. I love this book for many reasons. But most of all, my own son is about halfway through the book right now and he’s loving it. As a budding hip-hop artist himself, I’m so glad that this resource exists for him to know where this all came from and what tradition he stands in. So, thank you both for writing this book. And welcome. Let’s dive into the questions because we don’t have a lot of time. I have a few questions and I hope we can get to them all, but we’ll have to see if we can keep pushing through it. I wanted to begin by saying that in the new YA edition of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop you quote Scarface of the Ghetto Boys when he said, “Hip-hop became much more about delivering the truth and getting the word out about what was really going on in the streets of America, not just what Americans wanted you to see.” So, I was hoping you could talk about the ways that hip-hop emerged as a Black and brown youth response to, and I think in many ways, a rebellion to the neoliberal era, including the shuttering of social programs and the closing of community centers, and talk about the origins and emergence of this music. Dave “Davey D” Cook: You want to start first, Jeff, because you’re oldest? Jeff Chang: That’s not true, actually. Cook: No, that is true. It’s provable. Actually. Hagopian: Already playing the dozens. Chang: Yeah, no, this is me and Dave’s relationship, basically, in a nutshell. I’ll start, Dave, because you put me on the spot, and I respect my elders. Basically, we wanted to try to offer this as a resource, especially to you all folks. You’re the folks who continue to keep the stories moving. For us, it’s just a big honor to be able to talk about the work, with you all. Can’t Stop Won’t Stop began as a project when, simultaneously, Dave and I were doing books, back in the early 2000s, trying to document this emergence, or this iteration we could say, of the Black Freedom culture, and the Black film culture kind of stemming from the Black Freedom Struggle. For us, it was really key to be able to tell these stories of these young Black kids in the Bronx, in New York City, in Black neighborhoods in the 1960s and the 1970s, who are able to come together, despite being abandoned by everyone, virtually — by the government, by their own teachers, by the system — to forge their own way of being able to express themselves and to continue to pass on the movements, the rhythms, the dance, the music, the stories, and the visual art of their culture and their folks. So, the story begins really in the 1960s, against the backdrop of the politics of abandonment, and continues on through . . . Somebody here mentioned, I think it was Mr. Fuentes, talked about Los Angeles. We moved the story to the west coast to talk about the politics of containment that began to start taking shape in the 1980s and the 1990s, and that was where the original book left off. So, in this book we take it all the way up to last year, to 2020, and the uprisings around the murder of George Floyd, as well as the impact of the pandemic and the economic crisis on communities of color. But, it’s really important, I think, to be able to tell this story over again, because it’s simply an iteration of how the Black Freedom Movement has led us to be able to understand how unfulfilled the promise of American democracy is. And just the power of expression — hip-hop is Black music, hip-hop is American music, hip-hop is global music now. It’s the voice of young people who are oppressed all around the world, and many more than just that type of group. So we think it’s the greatest story ever told, and that’s what we wanted to try to capture. Hagopian: No doubt. Cook: Building off of Jeff, first, let me say what’s up to all the teachers here. You know, my wife has been a school teacher for many, many years, and it’s God’s work. So, I thought I was going to have an easy night off, but all the teachers are here so I’m like, she’s not here, but now she’s pulling up, so now I’ve got to really be on my p’s and q’s. She’s like, “You better not embarrass me!” So big shout out to all the teachers, for real. I see the work that she puts in and I can appreciate that, especially having two young kids myself who are going through the system. Building off of what Jeff said, two things come to mind. One, when we talk about the Black Freedom Struggle, we should be clear that there’s many iterations of the Black Freedom Struggle — there’s the Civil Rights Movement, there’s the Panthers, there’s SNCC, there’s all these different things. For me, more or less coming up in the Bronx in the 1970s, it’s the Black Power movement. Because even though the Civil Rights Movement, the whole Dr. King motive, was very powerful, there was also a rejection from that as well. Hip-hop was an embarrassment to many of those folks. And the nurturing that came came initially from people that had those connections — if not directly involved with the Panthers, the Nation of Islam — so it is that iteration of the Black Freedom Struggle, where you’re looking at the people who are left out of the doors that were opened. And I think that gets described in the reaction to these politics of abandonment that folks who are in the crosshairs of that — whether it’s through Nixon’s policies, or the mayor at the time in New York, or J. Edgar Hoover in the larger scope of things — these folks are reacting to the militancy and the Black Power struggle that was awakening a lot of people and saying, “Not only are we not going to turn the other cheek, we’re going to have a politic that challenges the system.” So hip-hop comes out of that kernel and I think we need to look at that. The other thing is that we start off and we focus on the Bronx, but the good thing about this book, and what Jeff had started off when he moved the story to the West Coast, was that we tried to look at this and understand that New York had a “unique” response to it. But that response is found in almost every place where Black folks are at — whether you’re in Oakland, where I’m at, whether you’re in LA, whether you’re in Chicago, anywhere you want to go. So while we have hip-hop in New York, you go to DC and they’re doing Go-Go, go to Chicago and they’re doing house, you go down south and they have a whole other song and dance and oral tradition that’s being manifested. What you have in common with all these expressions is that people were being left out, being discarded, being contained in some areas, or being abandoned in others. And what people wanted to do is tell their story, be seen, be heard, be acknowledged. And they found ways to do it. New York just happened to be a big jump off that eventually interacts with other jump offs in other cities, and we have this beautiful flourishing of hip-hop with all these different places, I think, adding to this culture and giving their unique expressions. But, the bottom line is that people were just left out, and folks were going to find a way to make a way. And here we are. Hagopian: Yeah, thank you all so much for that, grounding us in where this music came from and the political and cultural moment. Before I ask my next question, I just want to ask the educators here what made you choose to attend this session on hip-hop history? There’s a poll that we can throw up there, and if people can click on that we’d love to find out what brought you here. Did you grow up listening to hip-hop? Have you taught it already? Are you trying to figure out more about how to work it into your lessons? We’d love to know more about that. And I have four more questions, and we’ll see if we get to them all. But I want to just jump ahead and say that hip-hop has been as much a part of why I became a radical, why I became an educator, as anything else. I can remember listening to KRS-One. I think a moment that’s always going to stand out is when I was in the CD store and found Dead Prez’s album Let’s Get Free, and just the cover, I just knew I had to buy it and figure out what was going on with this. The songs, like “It’s Bigger Than Hip-Hop” or “They’ Schools” just almost knocked me down and just connected so much with my experience. They start that song “They’ Schools” off saying “the same people who control the school system control the prison system and the whole social system ever since slavery.” And it just got me really thinking more about the problems of education in terms of systemic and institutional racism, rather than the individual teachers I had that were a problem. So I wonder if you can talk about the ways that hip-hop has contributed to the Black Lives Matter movement and the importance of young people learning about the politics of hip-hop? Chang: The really amazing thing about this particular edition for us was that the original book had come out in 2005, and it ended in 2000. And my editor, Monique Patterson, who just gave us so much support and love, was like, “It’s time to take it to a new generation.” So we started writing this about three years ago. But we had to turn it in at the end of 2019. Things went a little bit long and we said, “Hey, we can’t leave out the stuff that’s going on right now.” And she totally agreed, and she sort of moved heaven and earth to be able to give us some more time to be able to do it. So we were able to capture, again, this new sort of uprising, upwelling, this spirit of change that we saw happening during the summer months. And hip-hop, of course, has been the soundtrack to all of that. What we’ve seen is that there’s been this really interesting discursive kind of dialectic between what’s been happening in the streets and what’s been happening with the art. We’re in a moment right now that feels like another renaissance of powerful music, powerful art, powerful filmmaking, powerful shorts that are being done, powerful writing that’s being done. There’s just so much and I’m sure all of you as teachers have been going, “Gosh, I know.” There’s so much to reach into, so much to present to folks in the YA field — all kinds of amazing authors from Jacqueline Woodson to Jason Reynolds, everybody that we can think of, Ibram X. Kendi’s new YA book that’s coming out as well. It’s been a really powerful time. What a time to be alive, as the kids say, right? For us to be able to talk about all this work and see the ways in which it’s manifesting in young people’s thinking and activism and learning. Cook: One thing that was going on in the 1970s as you started to have a clamp down on these freedom movements — there was a shift in terms of who got the mic and who was listened to. What you saw was very systematic: leaders were either executed, jailed, or silenced. Platforms that they had open were unavailable. And for a period of time, at least for my generation moving up, athletes and artists and entertainers became the people with big microphones. So, a lot of our hopes and desires and, and even histories, came through artists. That’s important to note, that celebrity culture was being born. It wasn’t completely controlled. Or maybe it was controlled in many areas, because people like H. Rap Brown, a.k.a. Jamil al-Amin talked about that, as well as others, that Black entertainers were working on behalf of the system. But hip-hop was one of these things that people didn’t see coming, and so for a period of time — for a few generations of people in the middle of the crack epidemic — it was hip-hop artists with a certain amount of politic and a certain amount of intentionality. Key word intentionality, meaning that their politic and their willingness to deliver information was not by accident. We’re talking about clandestine meetings that people had at places like the Latin Quarter, where they were like, “This is what we’re going to do when we get these microphones. This is what we’re going to do on these platforms.” There were people that were saying, “I will dedicate a song. I will make sure that I’m going to speak truth to power, because nobody else has the mic.” And so you had that sort of focus, like, “What is Public Enemy saying?” “What’s Big Daddy Kane saying?” “What is Queen Latifah saying?” And that went on for quite a bit of time. As we move into the Black Lives Matter era, you now have people who only grew up on hip-hop — they don’t know a day without it for people that are a certain age. And this has kind of shifted now; now we’re not necessarily looking for the artists to provide the education because there’s a lot of people that can speak for themselves and have platforms. I think now you see the artists kind of take the cues from the leaders, which is what it should have been from jump street versus the other way around. The industry, once they realized the influence of artists, really wanted to have us make those artists things that people followed. Once they could control the platforms and once they could get people acclimated to tuning into the Hot 97’s and the Power 106’s and the KMELs, then they could give them information. The information was designed to make us consumers and to keep us in a certain type of mindset. But now you have a lot of other people that broke out of that matrix and you see it now reflected in the music. If you see artists speaking out, say about the Ferguson Uprising, it’s because they’re seeing what’s going on in the streets and now they have to reflect that. So, you know, Lil Baby’s not leading the charge, Lil Baby’s looking at what’s going on in the streets and he’s saying “I better pen some lyrics,” right? The Ice Cube’s and everybody else, I think, have had to take leaders, leadership from what has been happening. The next step will be how we take all these collective resources and create something that is even more dynamic. I’ll close with this. We started to see a little bit of this, where artists fell back and let leaders take that role. I’ll point to the Million Youth Marches. One example of that, where Master P was like, “They’re trying to shut it down? You need money for permits? I’ll write the check. I don’t need to speak. I’m going to fund this.” That’s in the method of Harry Belafonte. As you know, Harry Belafonte since then got on a lot of artists’ domes for not doing more, and many of those folks fell back and started writing checks — “You all are in jail? I’ll bail you out.” “Y’all need some money to travel? We’ll make sure you’re there.” So, artists found, I think, a comfortable role so that a lot of activists can do what they need to do and not get caught up in the contradictions that we often pointed out about artists. “How can you say fight the power but you’re doing a song about sex or something like that?” “Well, we don’t need to know why I’m doing the song. The money from that is funding the people.” And I think that’s an important change that is happening. Where Nipsey Hussle and others were going, they were saying let’s get athletes, let’s get artists, let’s get business people in the community and see if we can buy a mall, see if we can buy a store. Let’s see if we can do those things. Those are things that were starting to happen. You can see that where we’re at, you can see that in other places, and it might not be for primetime but I think that’s the mindset of people right now. We don’t need the artists to necessarily lead, but to play a very significant role in the overall freedom struggle. Hagopian: I appreciate that. No doubt. It’s amazing to see that dialectical relationship between the struggle and the art, the streets and the hip-hop artists, that is making some synergy right now and pushing things forward. So, the poll results are in. Twenty percent of people have taught hip-hop history are currently teaching it that are currently with us. Thirty percent hope to teach hip-hop history in the future. Twenty-four percent grew up listening or studying hip-hop, and thirteen percent have never listened to hip-hop and want to learn. And thirteen percent said, “I just love all your sessions, so I did not want to miss this one.” So right on to you all who’ve been riding with us from the beginning. This time is going so quickly. We have about six minutes to get through three more questions, but we’ll see what we can do here. I want to ask y’all about the female MCs from Sha Rock to the Mercedes Ladies to Queen Latifah to Salt-N-Pepa to Lauryn Hill to Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion, who are just going so hard today. Women and b-girls have really been part of this music from the very beginning and yet they have also faced intense marginalization and sexism from the industry. I was hoping you could talk about the challenges that women have endured and the ways they have shaped the music and culture and the broader problems of the hip-hop industry. Cook: One of the things we didn’t want to do in this book was just have a token session where we go, “This is the women, Queen Latifah, MC Lyte, Foxy Brown, or whoever and move on.” It would have been inaccurate. Going back to what I said earlier, we are now charged with reflecting what’s going on in the community. So when I look out my window, the leaders that I see — whether they’re the Cat Brooks’ or Alicia Garza’s, I can go on and on. It’s women that are leading these movements, and so there’s an accountability factor. Jeff and I are married with strong women in our lives, so we’re not walking in the door, coming up short, being like, “How did you just write only one chapter when you know better?” I have a daughter, so you want to make sure that she has a blueprint, a robust blueprint, to look at. Lastly, there’s the truth. And the truth of the matter is that women were there from day one, whether it was DJ Kool Herc’s sister organizing the party and coming up with the idea, and being, arguably, the first entrepreneur in this thing called hip-hop — all the way up to what we see today, instant after instant where we can see that women have played key roles, whether it’s on the label side, whether it’s on the artistic side, whether it’s just in making sure that this culture and this movement have been able to thrive. There’s too many to name. So, throughout the book we were very intentional about making sure that in our storytelling of the story that we include the sisters that were involved from start to finish. And yeah, there is a section on women, but I think when you read the book you see that the presence is there throughout. That was important and very intentional and leaves us a lot of room to build on, because we couldn’t tell the full story without them. Chang: Right? I noticed there was a question in the chat about other resources, and we just want to recommend a few books. Actually, I think the classic, if you can get it used, is a book called Vibe Hip-Hop Divas, just a classic history, so well done. Some of the most amazing writers, our friends, our sheroes. I would also recommend Kathy Iandoli’s book God Save the Queens, which came out last year, a fantastic history of women and hip-hop. And if you want a book that you can just sort of inspire folks with, you should check out Clover Hope’s The Motherlode, which is beautifully illustrated and has profiles of a number of different artists. Just those three books, we would highly, highly recommend. Cook: I would just also add Joan Morgan’s When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost and she also wrote She Begat This: 20 Years of the Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, which everybody should know. That’s a great resource and it came out of the fact that we were dealing with promoters, that we’re having these showcases with like 50 artists on the bill and no women. When we talked to them, they were like, “Well, nobody wants to check out any women.” And so I got together with a number of women friends, MADLines to Aisha Fukushima. I mean we can go on and on, and we just put together a robust list, so that there would be no excuses. It had links to everybody, it went from all around the world. So if you were in Timbuktu, I don’t know, where there’s maybe no women, it’s like, “Nah, here are about a hundred right here.” So that was something that we used as a resource so that people could not come up with the excuse. And with the six hundred and some odd people, I stopped keeping track of the list maybe two years ago. So there’s a lot more to add to it. But it’s a good jump off for anybody who’s teaching and wants to go find some folks to build around. It’s a resource for you. Hagopian: I love it. I love it. I’ll ask one more question before we let teachers break into rooms. But we’re going to have to keep this short. Hip-hop has been such an important part of my classroom. In my opening unit about identity I often play a song by Big Daddy Kane called “Who Am I?” and in it he raps, “I was born a Black man from the Motherland, speaking the language today most people don’t understand, where no one could bother me because I had freedom, justice, and equality, but then one day it was taken away.” And we use that line to talk about how do we define where we’re from. I just want educators to understand how they can use hip-hop in the classroom as a source of knowledge that is more legitimate than the textbook and much more engaging, while also being sensitive to the fact that teachers can sometimes bring in hip-hop in performative ways that don’t really engage students in the criticality of the music. I was hoping you all could just share an excerpt of a song with us and talk about it before we jump to the break. We’ll leave everybody with some music and some thoughts about the music. So, we probably have to pick one. Jeff, I know you sent me a couple of suggestions. You want to hear “The Message” or “Freedom”? Chang: I think everybody’s heard “The Message.” What we wanted to do is to try to select two songs, kind of going back to the beginning of recorded hip-hop. So we pulled out Grandmaster Flash’s “The Message,” which I think most everybody here has probably heard a lot. We probably don’t need to play that. Another track that you might not have known about is called “Freedom.” And the beauty of playing these two tracks back-to-back is to kind of understand how hip-hop represents the range of different types of voices in the community. “Freedom” is a track that is really just about getting on the dance floor and being free. But you can take it as a metaphor for a larger sense of feeling, that sense of release that you might have, and that’s really what Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five did. They used to get up on stage and pass the mic and rock the microphone. “The Message” was actually a track that was done in response to the Reagan recession of 1982 that really displaced a lot of folks, left a lot of folks in the Black community unemployed, and communities of color unemployed. It hit communities of color, as you can imagine, much, much harder than it hit white communities, the beginning of Reaganomics. “The Message” was a track that, at first he said, “We don’t want to do this,” Grandmaster Flash said, “I’m not going to do this song because that’s not what our folks come to the clubs to hear.” But ultimately, it’s the song that got him into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. It’s the song that illustrated the power of hip-hop, to be able to express how young people are feeling at any given moment in their communities. And so we wanted to give people those two songs, “Freedom” and “The Message,” as a way to show within one group, within one album, whatever you want to call it, there are all of these different ranges of voices. It’s not that one is bigger or stronger than the other; it’s that all of them are being heard. Hagopian: I have a few questions myself that I still want to try to get to. But you can share highlights from your breakout group in the chat, just drop in something you learned, something that somebody said that sparked your imagination or curiosity. We’d love to see all that in the chat. If there were resources you learned about that we need to get on our resource list, drop those in the chat, as well. I’ll start off with a question and then we’ll see if there are other questions that come up from the group. Let me begin by talking about how conservatives have long waged a culture war against hip-hop. Kendrick Lamar quotes Fox News reporter Geraldo Rivera on his album, DAMN. That was just such a brilliant move, to go right after him like that. Geraldo says, quote, “Hip-hop has done more damage to the African American community than racism.” It’s just like, what, all of racism, really? Not slavery, Jim Crow, redlining? I mean, an incredible statement. But what really gets me is the way that liberals also really haven’t done much better. They decry hip-hop as just full of violence, a bad influence for our kids. And you all write in the book, quote, “The mainstream media has taken notice of hip-hop, but sometimes for the wrong reasons. Violence was also on the rise in rock concerts, but the media had a new reason to fix blame on use of color and call for rap show bans to spread.” So, I was hoping you could talk about what scares the establishment in this country about hip-hop. and what is the relationship of hip-hop and violence, including the way it exposes state violence in the lyrics? If you could talk about that. Cook: I’ll hit that first one. The attack on hip-hop needs to be contextualized. It’s an attack on Black people, [and] it’s an attack on people of color in general. We don’t have to be doing hip-hop, we can be protesting the police, and guess who’s being attacked and accused of being violent and all the things — BLM [Black Lives Matter]. When I was a student during the anti-apartheid movement, it had nothing to do with hip-hop, but guess who was depicted as violent, uncouth, problematic, all these different things? It was the people that were challenging power structures. So, I think when we talk about violence in hip-hop, we can’t separate it from the larger attacks that are levied on our communities, because we are challenging the system. The reason that it’s important to look at the book — the way it was written, in terms of how Jeff laid out the politics of containment and abandonment — because those are part of those attacks. And it has nothing to do with music; it has to do with folks that are trying to escape a position that is very profitable for folks who have a lot of power. I’ll close by saying Black pathology, Black death, Black dysfunctionality, is a multi-billion dollar a year business. You have Colin Kaepernick in the back. Colin Kaepernick has nothing to do with hip-hop, but he was attacked for the same reasons, with the same people in the same manner. And so we have to look at it that way. Lastly, to your point about the liberals, their response to Colin, to BLM, the Black Power movement, and even the Civil Rights Movement, Dr. King writes about it, was weak back then, it’s weak now. So what we’re talking about are people who still have a problem in recognizing our collective humanity and definitely have a problem with our leadership and recognizing our leadership and prowess. So, I don’t give too much airtime to the conservatives on this point because when we’re fighting the power, we’re here to knock them out and keep it moving. But Bill O’Reilly and those types of people are distractions from the politicians, who are — as in Florida, in Texas, and maybe in California — passing policies. Go after them and not the personalities. Chang: I’ll take the question in a little bit of a different direction. One of the big themes for us in this book is the dialectic between creativity and violence, creativity and state violence, creativity and violence in the community, as well, among young people of color. What we try to do, actually, is to talk about the organizing that happens within the communities amongst young people, solely almost, to be able to confront the violence that’s happening around them, and to be able to put together some sort of understanding of the real enemy that they’re up against. What happens in the history that we’re documenting over and over again is that young people are segregated, are pushed into deep extenuating circumstances, are pushed into poverty, and that state violence is enacted upon them, and then they, in turn, enact violence upon each other. But they figured out at different points in history how to get it together, how to come together, forge peace, and point their attention towards the real enemy. There was a gang peace treaty in 1971, that literally led directly to the foundations of the hip-hop movement in the Bronx. And then it happened again in 1992. Basically a couple of days before the uprisings jump off in Los Angeles, there’s this massive gang peace treaty that then spreads across the country. And that’s what they’re afraid of, right? Want to talk about Nipsey Hussle, when Nipsey Hussle was shot in the streets, this in turn led to a national gang peace movement, and out of that is this explosion of creativity that happens each time. And the finger gets pointed not at each other, but at the real problems, the real source of the issues, and that’s what? Power. The power of capitalism, the power of the government, has been turned on young people every time that’s happened. We see, as after the gang peace treaty in the Bronx, a shift towards increased policing against young people of color. That leads us into 1992, where the war on youth is accelerated after 1992. At this moment we could talk about what’s happening right now as well. So, that’s the thing that we wanted to point out, we do it through narrative, but right here we’re showing you our cards basically, the stories that we think it’s really important to be able to tell and retell. Cook: It’s an age old story, but America is profitable when it has a permanent underclass. When people try to escape being a part of that, it becomes a problem not just for the economic well being of certain people but, sadly — and this is where your point about the liberals come in — it’s how people identify themselves. I identify myself with you being less than me, and that’s a problem. So the resistance comes when I don’t give a damn about what you think — that becomes a problem. Very sincerely, I don’t give a damn what people think when it comes to that sort of situation, and I think many of the artists over time have said, “I don’t give a damn. I’m not even thinking about you. Go back to the Bill O’Reilly show where Cam’ron and Dame Dash were talking. Bill O’Reilly was so mad because they weren’t paying him any attention. Like, dude, I’ve got just as much money as you and we don’t care. When you do that, and folks who are used to seeing themselves as superior realize that they’re not, it becomes a problem. So I’m here for that problem. I’m here to be arrogant and, as we used to call it back in the days, as uppity as I possibly can if it makes you feel uncomfortable. That’s what we do. That’s what hip-hop has done. And more power to it: make them feel uncomfortable until they can go away. Hagopian: Right on. Jeff, you talked about how hip-hop emerged from a gang truce and some of that history and even the anti-violence programs that Nipsey was working on in LA. That’s an incredible story, and what a loss him being shot down was. I want to thank you for talking about his work because Nipsey Hussle was a cousin on my dad’s side, and my dad’s here [tonight], as well. Unfortunately, I never got to meet Nipsey, but even after all he did for the community and all his outspokenness against violence, he was shot down in front of his Marathon store. And his death was just so shocking. I mean, my dad was at the funeral and just saying it was so moving and it was so devastating, not only for my family, but for many thousands of people all over the world who mourn his death. So, I was hoping you could talk more about his contribution to hip-hop and his legacy. Chang: I’ve got to shout Dave out on this because Dave was one of the first very, very first people to interview a young Nipsey Hussle way back in the day. But I also want to mention, before I pass the mic real quick, our good friend, Rob Kenner came out with a biography of Nipsey Hussle this past year as well, The Marathon Don’t Stop. Hagopian: Oh yeah, my dad was telling me that it’s a great book. Chang: It’s a fantastic book, and Rob’s done an incredible job talking about Nipsey and his impact on the community. I daresay there’s a lot of teaching lessons in Rob’s book, but yo, Dave, just take the mic on this one. Cook: Well, I want to kind of look at the larger picture because it’s fresh on my mind. Yesterday, one of the major people who goes into the community and works with families who have lost loved ones to intercommunal violence, had his own son killed. A couple of months ago, a similar situation happened in Minneapolis. It happened in Chicago. And when you look at that, you look at Nipsey, you start to see that people who try to spark peace in our community — again, to end the chaos — find themselves either being surveilled, jailed, or curtailed in some form or fashion. Or even killed or suffering from some tragedy that has happened in the community. I’m always going to come back to this, even if we don’t necessarily spell it out in the book, but I think even when you read it, when we talk about the peace treaties and how the police beeline to disrupt it in any form or fashion from 1971 to 1992, you’ve got to remember that our piece is problematic for a bunch of people who profit off the chaos and dysfunctionality. So Nipsey, when you really look at all the things that he was doing, he was like, “Let’s get the athletes, let’s get the artists, let’s all combine forces and let’s see how we can do the very things that people said we should do” — pull ourselves up by the bootstraps, do it our own self. He wasn’t applying for grants, he wasn’t looking for welfare, it was like, we’re going to take our own money and do that. And it might have been a Marshawn opening up the store or buying up his entire block, it might have been a Ruff Ryders is doing similar things 3,000 miles away and then training people to run these things the way that LeBron trained his people, right? This was something that was happening in many communities with many of these artists, and every time [ended in] disruption. Lastly, we can’t forget about Ferguson, which is a major jumping off point in the book. Six of the main people that were involved in Ferguson were killed. You see what I’m saying? So, you can’t separate this, because when you look at it from afar you see all this disruption, and it can’t just be because Black people don’t know how to get along. This disruption is very intentional. It happened in the 1970s, it happened in the 1960s, it happened at the turn of the century, and it’s happening now. It’s camouflaged a certain way; it’s made to look like something that it isn’t. But I think when you just look at the pattern you go, “How the heck is this happening if it isn’t by design?” So that’s how I look at it. Hagopian: Thank you so much for speaking on his life and legacy. We have a lesson at the Zinn Education Project on how to teach COINTELPRO. So, I would invite people to learn more about that and its impact on the Black Freedom Struggle, and on Black artists. Cook: The first thing I show in all my classes, and people can write it down, is Darthard Perry. His name was Ed Riggs, code name Othello, he appeared in 1979 on ABC’s Like It Is, and he pretty much says the FBI collects and makes it a point to understand Black culture. They have a bigger collection and understanding of it than the Schomburg Center. When asked why he says “to know people you’ve got to know the culture, and then use the culture against the people.” He was responsible for burning down the Watts Writers Workshop, and he said they did it to demoralize the community. Then, when you check out all the information, it was absolutely true what he said and one hundred percent of the impact that it had. I think we’re always aware of that, so when we can exercise excellence and exercise a certain amount of agency, it’s done in a spirit of like, “I’m smashing back on you, Goliath, and we’re David with stones, hitting you in the eye, face, knees, everywhere. We’re not going to lose.” And that’s that bravado, that’s that confidence, that hip-hop has. When people see it, they want to redirect it. But if you’re smart enough, you don’t fall for the okey doke. Forget Bill O’Reilly, I’m looking at you, Greg Abbott, or Ron DeSantis, or Larry Elder. I’m looking at these folks, and that’s who we’re going to keep our focus on and make sure that the heat is on them 24/7. That’s how it’s got to be. That’s what hip-hop was about, that’s what hip-hop should continue to be [about], and it’s up to us to remind our students; that’s what it’s about, that they’re part of that legacy of resistance with a focus. Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. I’ve got one more question before I get to a couple of questions from some of the teachers here, but I was hoping you could talk more about the industry of hip-hop and the trajectory of the music from beginning as rebellious youth culture now to one of the most influential cultures in the world, and about how hip-hop has been commercialized in many ways and the industry has distorted and used the music. Chang: Where to start, where to start. One of the things we tried to do in this particular version of the book was to outline, literally, from Sugar Hill Gang putting out the first record all the way up through the industry shutting down the mixtape trade, even now into the new internet economy, we tried to illustrate the changes that have happened structurally. And it’s a similar kind of struggle there. It’s a similar type of thing where at every point where the big money wants to turn hip-hop into a mono culture, just representing certain kinds of voices on this entire spectrum of voices. Folks have figured out different ways around it and tried to come back at it. And so we talk a lot, for instance, about the role that independent radio and independent journalism and media play in establishing these ecosystems in these different types of cities. Like the reason that Atlanta has been so strong is because it’s got a really amazing ecosystem of folks, from shop owners to places where DJs play out to the mixtape culture to the artistry. Part of what we’re trying to get young folks to understand is you’ve got to build this, you’ve got to be able to build this yourself, separate from big money. It’s not about trying to get the big contracts, it’s about really building stuff up from the grassroots for yourself. Hagopian: Excellent. Davey, do you have something you wanted to add? Chang: Can you repeat the last part of that question that was said, and the information about Darthard Perry for folks? Hagopian: No worries, just talking about how hip-hop has become commercialized and how the industry has used it. Cook: Well, I think this culture, in a business sense, is about commodifying anything and everything you possibly can. The way around it is to know the history of hip-hop. I mean, hip-hop is not immune to that; it comes from a rich tradition, it comes out of the pain and struggle that people are dealing with. And somebody goes, “Wow, somebody’s talking about broken glass everywhere and talking about the hood,” the response should be, “Why is he saying it about broken glass? Can we clean this up?” The business response is, “He’s so angry and his rage is so beautiful, and we can make money. So let’s see if there’s more broken glass and more people singing about it, and let’s encourage that so we can make a profit.” That’s always going to be the case. Sadly, it is until we get into positions and we’re very intentional about saying, “This person is doing a poem about rape, we don’t want to make money about it, we want to end it. This person is doing a poem or song about racism and the horrors of it. We don’t want to hear more of this. We want to be moved to action, and we want to take those steps.” Hip-hop, when it gets distorted, gets distorted when folks come along and say, “We want to take the freedom message out of it and say that it’s dangerous, or it’s inappropriate, or it’s something that we shouldn’t really tackle. Or we’re offended by it; that’s the new thing. “I’m offended by it.” And in the meantime, we’re going to replace it with things that fit the ethos of the music industry, which is sex, drugs, and rock and roll. And now hot takes, right? How can you be contrarian to anything that is said. And so, as they say, we’re going to have to stand on a square as educators, we’re going to have to stand on our square as elders to the people that we teach, and show, and prove. So, when I go into the classroom, I’m very clear — I’m not here trying to quote Young Thug, I’m not going to pretend that I know every lyric by Megan, even though I DJ every week and do. That’s not the point here; I’m here to make sure that you have the tools to navigate a system that will bash on you. And it’s already bashing on you because you’re already in consumer mode rather than in critical thinking mode. You have to remind these folks that they’re coming up at a time where taking the test and passing the test is the goal versus learning the lesson. That was No Child Left Behind. So, you come with that sort of passion, you come with that sort of energy, and you’re unwavering with it, and people might not hear it initially but they feel where you’re coming from. So, when we’re doing hip-hop, people have got to feel you, they’ve got to feel that passion, and they’ve got to feel like you are serious about it. So, even if you don’t know the Young Thug lyrics they know that you understand the game that’s out there, and that it’s from love and it’s from a deep sense of caring that you’re trying to make sure that they get out of the trap that’s been set for them. So I don’t expect corporations to do that. My job at this point, and our job, is to expose the nonsense that corporations do. To tell them that the iPhone 12 or 13, why is it a news story on every single TV station around the country? You’ve got to show them, “Oh, this is an advertisement camouflaged as a “news story,” right? So what else are they camouflaging as new stories?” Then let’s start giving them an opportunity to understand media justice and media literacy. That’s our job. So we should not be surprised that a devil is acting like a devil. Our job is to shame the devil and quite literally kick his ass. Excuse my language, but we’ve got to come with that sense of boldness. Hagopian: Right on. I’ll be right there with you. I’ve got a couple of quick questions from the audience and then I’d love to just hear some thoughts about where this music is going today. Somebody said, “I would love for Jeff and Davey D to talk about Afrobeat and Reggaeton, and I would love for them to discuss how they see them moving hip-hop forward and actually moving the culture, how do they allow new voices to emerge?” Do you have any thoughts about that? Cook: As a DJ, with the very popular genres of music that we play from the American perspective, and this is coming from traveling, we’ve been very ignorant to stuff that comes outside of our borders. So in some regard, knowing that folks out of Nigeria have a music form and people are actually dancing to it, to the Wizkid, and Mr. Yash, and all those other guys, that’s great. We’re not even going to discuss the subject matter because we just want to make sure that people understand that there’s more than the American voice that’s out there, that it’s everywhere. When I hear people in a club, if I’m playing Reggaeton or some hip-hop artist that’s speaking Spanish or French or Swahili, or any other language, that’s good in a country where people say “English only.” Even in Black communities, where they know English only. So I think those are good steps that are taken. I think where we really find the story is overseas, where the folks in Canada know about the people in England and England knows about New Zealand and New Zealand knows about Brazil and Brazil knows about Tanzania — where that global cipher is understood and people not only know the music but they understand the politics. As Americans we’re late to the game, and I think the steps that we can take, again as educators, is to bring those folks that are coming from other countries and speak other languages and see how we can connect on common ground and allow those expressions to flourish. What’s the, quote unquote, “Latino” take on hip-hop? What is the “Asian” take on hip-hop? How are they seeing it? Are they mimicking it? Was it commercialized or are they bringing their own cultural aesthetics to the table? And how can we dissect that and uplifted and have appreciation for all of it? So, I think that’s where we’re at right now, learning a new language and appreciating that America — meaning all of us at this point — will not be centered. And I think that’s a hard thing for us to get; we go overseas and demand everybody speak English, and people are looking at us, like, “Son, I speak five languages. Why don’t you speak at least another one?” It’s time for us to step up and be a part of the global world. Chang: As far as a teaching tool, we’ve got a chapter on hip-hop’s global impact. We dive into how hip-hop has taken root in Brazil, in South Korea, in Senegal, and South Africa, and it’s really, really crucial, I think, for folks to be able to understand the way that, as Chuck D used to put it, our good friend, Chuck D, is that the 48 states are like a box, and Americans refuse to get out of the box. We just think everything should be serving us, but if you’re a b-boy or b-girl, or you’re just in the dance community, you know that ship has sailed a long time ago. If you’re in the graffiti scene, if you’re doing music and that kind of stuff, you know that ship has sailed a long, long time ago. So, what we try to do is just show how the continuities, the inspiration that folks have drawn from the Black Freedom Struggle, is rooted in literally every country on every continent all around the world. Cook: We try to remind people that part of the Black Freedom Struggle was to internationalize the struggles. That’s why it was important, I think one of the songs that I wanted to show was Queen Latifah’s “Ladies First,” because in that song it was very intentional and very subversive. Her and Fab 5 Freddy, based upon those clandestine meetings, said, “Let’s do an anti-apartheid video, and let’s show folks in Soweto and all these other places fighting against apartheid while we’re singing ‘Ladies First.’” So, you’re going to love the lyrics. Then, when you look and go, “Damn, she’s toppling apartheid?” Again, it was like, let us connect our struggles with the struggles of other folks. When we were talking about Ferguson, and they are connecting with their Palestinian brothers and sisters, those are important moments, because now when you talk to those folks, they stay in touch with each other. They’ve been to these countries now, or they go on to the United Nations. Those are the stories that we have a responsibility to tell people when we get into these classrooms. That’s what I tell them and try to bring some of those folks in because they’re accessible. They’re not A list artists; they’re there around doing work. So you can get Rebel Diaz, who was right down in Chile, who has a whole in depth and very, very nuanced and very precise critique of hip-hop and neoliberalism. You give the mic to them and let them break that down and understand that they are dope MC’s. Same thing with Immortal Technique. I mean, we can go on and on with folks that are really getting down. There’s a lot of women — [illegible], Mystic, Rhapsody — who we mentioned, these are folks that have deep and rich politics that we need to lay out to folks so that they understand, it’s okay to be intelligent, it’s okay to have a politic, and it’s okay to use your talent for the benefit of the community. Hagopian: Thank you so much for that. That connects with what somebody said in the chat, that hip-hop artist as a first responder, and the arts being a creative and spiritual resistance and healing in the face of state sanctioned violence, I think so much of the artists and history that you have brought up is about that culture of resistance. I just want to thank you both so much for your time this evening. It’s been a really rich discussion. If you have any last resources that we should know about, and we have to give people time to fill out the evaluation, so I hope no one will drop off. We’re going to drop the link to the evaluation right now in the chat and we hope everyone can stay and be sure to fill that out. As you’re filling that out, any last resources you think educators should leave with? Chang: I want to just speak to the notion of the artist as a first responder and artists as healers of the community. I mean, one of the things that many of us came together to do last year was to write this piece called the Cultural New Deal. What we try to lay out is an understanding of artists not just as entertainers. Racial capitalism would like artists to just be reduced to entertainers. We know, obviously, that artists can be teachers, that artists carry on and distribute bodies of knowledge, and take them on from generation to generation, through art, through song, through music. But one of the things that we’re trying to do is to get people to adopt the ideas of cultural equity and cultural justice. Cultural justice speaks to the ways in which our cultures have been marginalized, but not just that, suppressed. People have died for our culture, we’ve had our languages erased. And one of the beautiful things about the Black freedom culture is it reminds us of the power of continuity, and the power of being able to provide that point of view that includes a place for everybody. So, cultural justice is really about trying to reverse that erasure, that marginalization, that suppression, that cultural genocide that’s occurred. And I don’t think enough people are talking these days about cultural injustice, the cultural injustices that have been done to us. So, in that context we’re not just the people that are keeping communities together and safe and healing us during this time of a pandemic, and an economic displacement that’s bigger than anything since the Great Depression. We’re the folks that are helping hold it together. Artists are essential. Culture bearers are essential. So, that’s something that we put out in this thing called the Cultural New Deal. Take it and use it in your communities to help to transform the way that we see artists and the way that we understand culture. Hagopian: I love it. Thank you so much. Thank you so much, y’all. Unfortunately we have to leave it there but I greatly appreciate that resource. I hope teachers will use that. Cook: First of all, to the teachers, thank you for the work that you all are doing. You all are the frontline in this, as I said in the beginning. I think it’s important that the work that we do underscores the values that you’re imparting on the youth, that it’s not in sharp contradiction unless it’s just you out there doing something that is counterproductive. I think there’s some good lessons to learn from a book called King Maker by Marcus Goodloe, who talks about the role that Dr. King played and the strategy that he used to engage people with big mic, celebrities. I think there’s a lot of lessons to be learned and can be imparted to the youth that you teach. How he used celebrity culture, how he engaged people, from having a council of elders to having talking points so that when people with big mics got in front of the world, they knew exactly what they were doing. I would also look at the new movie that’s on Netflix, I think it is Blood Brothers about the relationship between Dr. Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali. I think there are some good lessons to be gleaned there. Again, what we’re talking about are people who are thrust in the spotlight and people who are doing the work on the ground. How do we merge those two? For us in the classroom, it’s how do we take that celebrity culture and make it relevant to people that are in your classroom to understand that they can do more than just be a celebrity, that they can actually be a king maker, literally, as the book said, or queen maker, or somebody who is out there making it happen. That they don’t necessarily have to sing and dance and do all these things. But they can support and facilitate the politics that we need to have. And I think both of those resources lay that out. There are a lot of lessons to be learned, and they apply directly to hip-hop, because we’re part of the hip-hop generation. Marcus Goodloe is from our school. Hagopian: Thank you so much, Davey D and Jeff Chang. If everybody could unmute please and show some love for these two. While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Transcript

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the books, films, podcasts, and more recommended by the presenters and also by participants.

Related Books and Articles

|

500 Female Emcees Everyone Should Know (Davey D’s Ultimate List) by Davey D Hip Hop Speaks to Children: A Celebration of Poetry with a Beat edited by Nikki Giovanni King Maker: Applying Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s Leadership Lessons in Working with Athletes and Entertainers by Marcus Goodloe When the Beat Was Born: DJ Kool Herc and the Creation of Hip Hop by Laban Carrick Hill The Motherlode: 100+ Women Who Made Hip-Hop by Clover Hope God Save the Queens: The Essential History of Women in Hip-Hop by Kathy Iandoli The Marathon Don’t Stop: The Life and Times of Nipsey Hussle by Rob Kenner When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost: A Hip-Hop Feminist Breaks It Down by Joan Morgan Hip Hop Family Tree by Ed Piskor Hip Hop Divas by Vibe |

Lessons and Curricula

|

COINTELPRO: Teaching the FBI’s War on the Black Freedom Movement, teaching activity by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca Rhythm and Resistance: Teaching Poetry for Social Justice, teaching guide edited by Linda Christensen and Dyan Watson |

Films

|

Blood Brothers: Malcolm X & Muhammad Ali Hip Hop: The Songs that Shook America – Queen Latifah’s “Ladies First” |

Podcasts

|

Dissect Podcast – Kendrick Lamar |

This Day In History

|

Music

“Freedom” by Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five

“The Message” by Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five

“Freedom” by Ras Kass and DJ Free Leonard

“False Knowledge” by South Seattle Swagger

This song is by a middle school duo from Seattle, Triple S (South Seattle Swagger) – Mc’s Freeze 32 and Gucci Grape.

“Police Get Off My Block” by South Seattle Swagger

This song is by a middle school duo from Seattle, Triple S (South Seattle Swagger) – Mc’s Freeze 32 and Gucci Grape.

Participant Reflections

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

Hearing about the patterns of resistance and creativity that we see in the history of hip-hop.

I liked the resources — songs, books listed. I also like the general community feel. It feels affirming knowing you’re not the only one doing this work.

The importance of a diverse set of voices and perspectives within hip-hop culture when we are teaching it and the concrete political origins and ongoing engagement within hip-hop.

I loved how Jesse layers his convo facilitation to get at the tough stuff and the power/resistance message so we stay strong in the struggle.

That hip-hop is almost-always political. And while I didn’t learn this today, what was reaffirmed is the essential nature of artists.

The tension between those who are trying to use hip-hop to teach and change things for the better and those who simply want to use it as a commodity, losing the message in the commercialization.

Positioning hip-hop in its rightful place in the struggle

The most important thing I learned today was that I was justified in my criticism of the absence of hip-hop music and culture in modern-day academia, given the fact that hip-hop (and other aspects of African-American history & culture) are the tastemakers of society today.

I have learned that the value of hip hop is not just for the Black and Brown community. It is for everyone to understand not just the culture of hip-hop but what our students value. This is important to connect with them on a higher level.

I think it was important to hear Davey D’s statement on using hip hop in education, not being intimidated, even if you do not know the lyrics, showing that you truly understand the struggle behind the movement is powerful.

What will you do with what you learned?

First, dive into these resources. So much was shared, and I’m excited to bring them into my classroom. Second, find ways to make the resources digestible for second language students. My kids here have a genuine curiosity for all things foreign, and they will devour this information if it’s presented in a way that they can process and interact with.

I will share these resources with my students in teacher education courses and use it myself in both education courses and my college history courses.

I will continue to use hip-hop to teach social justice to my students as well as allow them to use it to have a voice.

I am a new learner of hip-hop. Not ready/qualified to teach this material (yet). But will ask students many more questions and listen much more closely to the lyrics and names, and encourage them to see/find social justice potential in these. And I will keep learning.

Mindfully and intentionally inspire my students to practice courage and speak truth to power

I will use this info and the sources to build a unit on the history of hip-hop and protest.

I have a colleague teaching a history of hip-hop class this semester; I will check in with him to see what resources he is using and share the ideas that were gathered here. I’ll also be listening to a lot more hip-hop. . . especially with our son, Charlie!

I plan to have my students analyze song lyrics the way we already do with poetry. They can then replicate the songs using their own lyrics and message.

Continue to look for ways to bring lyrics and songs to better understand political and cultural moments. I need to be more intentional in the connections I make between “The Message” and the failures of the Reagan administration

I will get back into hip hop more. . . I’ve been looking for women MC’s and I got a lot of references here… I’m so happy that politically engaged hip hop is alive and well. . . I want to study this in its global context through my own listening engagement.

This year I’ll be teaching an elective for seniors called “Community Organizing: People, Power and Change”. I plan to bring in hip hop history as a prime example of youth building power, resisting through creativity and joy along with actions like the gang treaties. I just ordered the YA version of Can’t Stop Won’t Stop — I’ve been buying and sharing the original version with people for years!

I am excited to finish the book and continue learning through the resources shared today. I am excited to add to my unit of protest music. Also the great idea I got from my breakout group to use the form of hip hop and protest music to has students tell the story of another part of history.

Additional Comments

I just want to say thank you to Jeff, Davey D, and Jesse for that amazing conversation, and a special thank you to Jeff and Davey D for your early support of my journey with and love of hip hop. The high school where I teach is going through a lot right now and this reinvigorated me and gave me so much energy and inspiration, and I’m grateful that I can now bring that to my students. Thank you!!

This was awesome. Thank you so much, Mr. Davey D and Jeff. So nice to put a face to the voice I know from KPFA (Davey D). Thank you for awesome facilitation Jesse and Deborah and others for all of the behind-the-scenes.

Thank you so much for this event. I mentioned in the chat that I don’t have access to many resources like this in China for PD. It was refreshing and motivating. I had the privilege of hosting Howard Zinn for a talk and small dinner at my university years ago, and the things discussed in this session, the format it took (interactive, open, helpful and actionable), the knowledge I gained from it. . . I found myself repeatedly thinking “This IS Zinn. This is an embodiment of everything that he fought for. This legacy is a perfect reflection of his work.” Thank you so much for that.

Presenters

Jeff Chang is a graduate of ‘Iolani School, the University of California at Berkeley, and the University of California at Los Angeles, and has written extensively on culture, politics, the arts, and music.

Dave “Davey D” Cook is a nationally recognized journalist, adjunct professor at San Francisco State, hip-hop historian, political commentator, syndicated talk show host, radio programmer, media justice and community activist.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, and editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn