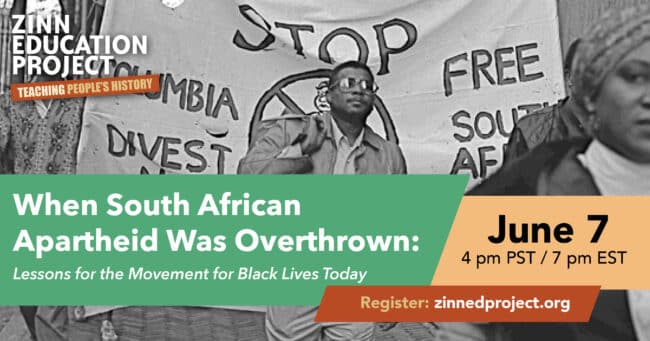

The struggle against the racist apartheid regime in South Africa was a global rebellion that included many Black people in the United States. African Americans saw the parallels between the system of white supremacy in South Africa and the one in the United States. This struggle holds many lessons for the movement for Black lives today.

Gerald Lenoir, a veteran organizer of the anti-apartheid movement in the United States and an organizer for racial justice today, will share lessons from the movement that helped bring down apartheid to help us better understand how to teach — and participate in — the ongoing Black Freedom Struggle.

Here are a few reactions from the participants:

I loved the way that Mr. Lenoir emphasized the role of students doing the steady work of showing up every week, in their own city, and how groups of students and other regular people all around the country and the world were able to accomplish their goal!

People fought so hard for Black Studies in schools.

Honestly, just hearing testimony was critical. Mr. Lenoir’s stories made me remember where I was during all the fights of the 70s. I wonder what stories my students will recall in 40 years.

I so appreciated all aspects of today’s event. Thank you to everyone who facilitated, emceed, and contributed. Thank you to Mr. Lenoir. This was the first time I attended one of these events, and to hear from people whose works I have followed and read for years was very inspiring and humbling. Thank you.

Find highlights of the session, a video recording of the class (except breakout room segment), recommended resources, and more participant feedback.

Video

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion. Jesse Hagopian: Pops, welcome. I’m so glad you could join us here. Gerald Lenoir: Thanks for having me. You’ve been telling me about it for months now, so I’m glad to be here with you. Hagopian: Good, good, good. I’m excited for this session because I had you come present in my classroom, when schools were still open in-person, on this very topic about the movement against apartheid. My students got so much from it, so I wanted to make sure that all these educators and students here today, that we’re transmitting these lessons that are so important. Internationalism and pan-Africanism, these things have been so important to the Black Freedom Struggle. Some of the sessions that we have done throughout the year have touched on some of these issues, but maybe not fully in depth like we’ll do today. We covered people like Paul Robeson, who had a really important commitment to internationalism and uplifting the Black diaspora. So, I wanted you to speak about the importance of understanding the Black diaspora and an international approach when we look to the Black Freedom Struggle. Lenoir: Yeah, so you know, Jesse, I came of age in the 1960s. With that came a real shift in consciousness. I was born colored, a negro, and during that period of time we became Black. To call somebody Black at that period of time was an insult. It was fighting words. But we transformed ourselves into Black people, saying, “Say it loud, I’m Black and I’m proud.” With that came a recognition of our African roots. During that period of time, in the 60s, the struggle against colonialism on the African continent and in the Caribbean was at a fever pitch. Those struggles began to inform who we were as young people, and it began to seep into our consciousness that we were people of African descent and that it was something that we should be proud of. Some of the activism in the 60s and the 70s, with activists connecting with liberation movements across the African continent and in the Caribbean — bringing speakers from the ANC [African National Congress], from SWAPO [South-West Africa People’s Organization] in Namibia, from MPLA [People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola] in Angola, all of these liberation movements coming to the U.S. — really began to change our consciousness about who we were as people of African descent. [It helped us in] really understanding that the struggle against anti-Black racism, against white supremacy, is an international system, in that we needed to connect with our brothers and sisters on the African continent, in the Caribbean, and indeed, throughout Europe, where the struggle of Black people was being waged. So that, for me, as a young man growing up, was really critical for me to identify who I was in the world, not just in this country. For folks like me, I know some of the folks that are in this session understand and went through the same things that I went through. Hagopian: Right on. It must have been an incredible transformation. It is just hard for me to even wrap my head around the kind of huge cultural shift that occurred in your generation. I feel like we’re beginning to see a new emergence of a radical struggle. But we’ll get to that. I want to ask you now, beginning to focus in more on the topic for today about apartheid, could you explain for folks how the South African apartheid system worked to oppress Black people, and even mixed-race people and and other other people of color, and also why did Black people here in the U.S. see similarities with our own system? Lenoir: Apartheid was an extremely brutal system of complete separation and domination by the white minority. But by the 1980s South Africa was composed of 65 percent people of African descent, African peoples. That was like 18 million Black people as opposed to 4 million white people, and 3 million people of mixed race — or colors, as they were called, are still called — and approximately a million people of Asian descent. You had this tiny minority who implemented the strictest separation, apartheid. They occupied eighty percent of the land. And not just any land, the most fertile land in South Africa was occupied by the white settlers. They forcibly removed people from their lands and put them in what were called Bantustans or homelands. That was twelve percent of the land, and it was the most desolate land you can imagine. I’ve been to some of those Bantustans and really, they were uninhabitable. Yet people were forced to move there. There were a series of laws that made it legal to detain people without any charges for months and sometimes years. There was a prohibition against mixed race marriages, there were prohibitions against demonstrations, and so there was a very strict and oppressive system of racial separation and racial oppression. And during the course of the anti-apartheid movement in the U.S., we made the parallel between apartheid in South Africa and Jim Crow in the U.S., and it really struck a chord with folks in the Black community because they could see that there were striking similarities in the racial separation and the oppression going on in South Africa and in the U.S. So, as a young organizer during the anti-apartheid days, there was a focus on how we could show solidarity towards each other and understand each other’s struggle. What I found was a ready audience among Black people to understand what was going on in South Africa because it’s so egregious, because it so paralleled our experience here in the U.S. Hagopian: Yes, yes. Thank you for that. So, I want to get into how you joined this struggle and how you joined the Black Freedom Movement at all to begin with, and how specifically you decided you were going to spend your time fighting against apartheid in a country far away. Why prioritize a struggle against racism in South Africa when there’s a Black Freedom Struggle here at home going on? I also hope you can share some of the stories about your time at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and that Black Student Union organizing and the fight for Black studies there. Lenoir: Madison was where I really came into political consciousness. I went there in 1966 as a freshman, the same year that the Black Panthers were founded, and the same year that Stokely Carmichael espoused Black Power as an ideology and a politic. It was a time when Black students were coming into our own to try to understand who we were in the world and to demand our place in the United States, and in the curriculum of universities across the country. In 1969, our student leaders, Black students and union leaders, called for a student strike until we won Black studies and demands for more Black professors and for more Black students on campus. We struck for about eight days [until] we were brutally repressed by the police, by the National Guard, [who] tear gassed us. They beat many students, they suspended students, they jailed students, yet we still won the Black students’ struggle. Hagopian: I just feel like people need to know that history, even us having this conversation right now, about how do we get Black studies going again, for folks to know that it took people getting their heads cracked and tear gassed to even have this conversation, right? Lenoir: Yes, this was going on across the country. Madison was one of over 100 universities, both white institutions and Black institutions, that were on strike until the demands were met throughout the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. This was a massive part of the Black Power movement in this country, and that is what brought me to consciousness — that social movements can make social change, that they were critical to social change. By the time I got to Seattle in 1973, I was prepared to be a part of social movements. I ran into and met [someone] who is now a good friend of mine, and now my boss at the Othering & Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley, john a powell, who was at that time an attorney at Evergreen Legal Services. He involved me in the American Friends Service Committee, which is a Quaker peace and justice organization that’s national and international. I was hired by them and I organized an anti-apartheid project in Seattle and began my work in the anti-apartheid movement in 1977. This was the year that Steve Biko was brutally murdered by the apartheid regime. Steve Biko was the leader of the Black Consciousness Movement that arose after the Soweto Uprising in 1976. Soweto was the uprising in which high school and junior high school students took to the streets across South Africa to protest the education system, to protest the fact that the Afrikaners were imposing the Afrikaans language as the primary medium of instruction in the schools. The students knew that if they were taught in Afrikaans that they would be isolated in the world because South Africa is the only place where the language was spoken, so they took to the streets to protest that. As we were in 1969 in Madison, they were met with brutal repression. Hector Pieterson was the first student to die; his name went down memorialized in history. And the demands began to grow: to dismantle the education system, to dismantle apartheid. That marked the beginning of the end of apartheid, and brutal repression came down. The next year, Steve Biko was murdered and the movement continued to grow and grow and grow. I was an organizer in Seattle during that time, and going to community events, going to colleges, going to universities and churches and private homes. And always met with, “apar what, apart? Can you pronounce that for me?” But within six or seven years apartheid became a household word, both in terms of organizers like myself across the country that were doing the work that I was doing — organizing small events and large events, bringing speakers from the ANC and the PAC, African National Congress of South Africa and the Pan Africanist Congress, bringing speakers from all the other liberation movements, from Namibia and Angola and Zimbabwe — really making the connection with the liberation movements on the continent and our struggle in the U.S. In bringing the consciousness that the struggle, as I said before, against racism and white supremacy was an international struggle, and that we could not win the struggle at home unless we connected across the world and began to lift up our struggles as one. So we organized in Seattle. We had a gentleman in Seattle who volunteered to be the counsel for the South African government, he represented the South African government in Seattle. We held weekly demonstrations at his house for years. Every Sunday we were out there demonstrating. We’d go up to the steps, the police would come and say, “You’re trespassing. If you don’t leave, you’re going to be arrested.” We’d tell them, “We’re not leaving until apartheid is dismantled.” They handcuffed us and took us to jail and then scheduled us for preliminary hearings. This went on, as I said, for years. At one point, we had over 100 people scheduled to go to trial, and we got massive publicity out of that campaign. Every weekend, the demonstrations on Sunday were on the Sunday News, were in both newspapers on Monday morning, were on the Monday Morning News. There was a tremendous amount of momentum and support and this was going on across the country. Some of you who were there during that time remember the demonstrations that were going on at the South African Embassy, Randall Robinson and TransAfrica Forum and the Southern Africa Support Committee. We’re organizing those demonstrations every day, with folks like Harry Belafonte and Stevie Wonder and Walter Fauntleroy, all these folks every day getting arrested at the South African Embassy that sparked the demonstration that we had in Seattle. It sparked, here in the Bay Area, the Longshoremen refusing to unload boats that were hauling cargo from South Africa. All over the country, people were responding to the call. By this time it was 1984 and coming off of the Jesse Jackson campaign for president in 1984, we went right into the anti-apartheid movement — I became the co-chair of the Seattle Coalition Against Apartheid. We started these demonstrations and it became a really, by that time, I said, apartheid had become a household word, so we moved from just strictly doing educational work to really lifting up this struggle in a way that had never been lifted up before. Hagopian: Yeah, that’s beautiful. I just have a last question about what were some of the demands you guys raised in the struggle? What do you think the impact of this international solidarity campaign was in the ultimate defeat of the apartheid regime? Lenoir: So, the ANC had a strategy that the international movement was a critical part of. Their slogan was “Make apartheid unworkable. Make South Africa ungovernable.” They had an alliance on the ground of the ANC, the South African Communist Party, and COSATU, the Congress of South African Trade Unions. On the ground they were organizing through the United Democratic Front to implement that slogan. They called upon the international community to support their liberation through boycott, divestment, and sanctions [BDS]. And so we organized those things: boycotts, divestment, and sanctions. We boycotted CityFirst Bank, which is now Bank of America. CityFirst was making loans to corporations in South Africa. We held demonstrations in front of their headquarters and burned our checkbooks in protest of those loans. We called on the U.S. government to divest from South Africa, to pass a law to make corporations divest from South Africa. We boycotted IBM and all of these corporations that were doing business in South Africa. It was a very active campaign to bring the consciousness of how U.S. corporations and the U.S. government were supporting apartheid. Congressman Ron Dellums from the Bay Area, year after year after year, had been introducing the anti-apartheid act. Well, in 1986, with Ronald Reagan as President at that time — the most conservative president in modern history — the Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986 passed. It went to Ronald Reagan’s desk and he vetoed it. It came back to Congress and it passed the legislation over his veto. This was due to the mass pressure that was on the ground every day, from the movement in the U.S. and across Europe and across the world, and in South Africa, that came together. And the freedom movement leaders in South Africa credited the anti-apartheid movement across the world for helping them end apartheid. Hagopian: You got to meet Nelson Mandela, right? Lenoir: I did. I went to South Africa in 1984 for the election. I was a journalist for the Oakland Tribune and for Black Scholar magazine. So, I covered the election. I stayed in Duncan Village, which is the second largest township in South Africa, in Mandela’s home province of the Eastern Cape. I worked for an ANC office during the election, for 12 hours a day, working to get the ANC elected and to get Nelson Mandela elected. I went to the inauguration and wrote about the inauguration. I didn’t meet Nelson Mandela at that time. When I did meet him was the first time he came to Seattle. I came as a journalist and as an anti-apartheid activist and they flew him into Boeing Field and they allowed several of us from the ‘84 movement to go into a reception area to meet him and his wife, Graça Machel. We spent 20 minutes with him and told him a lot of the history of what went on in Seattle. Really, that was the highlight of my life, to meet Nelson Mandela. Hagopian: That must have been incredible. We want to come back to our topic, and I’m really curious what people remember about the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. Maybe you were a kid and you remember something, or maybe you were an organizer in the struggle. If you want to drop in the chat anything you remember about that time, that will be cool for people just to get a sense of what you experienced in the struggle. Then, to bring it full circle, the first online people’s historian class that we did was with Dr. Jeanne Theoharis, about The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks. In our breakout room we realized there’s this picture of Rosa supporting the anti-apartheid struggle. Jeanne, if you just wanted to talk about that real quick. That would be great. Theoharis: I think it really echoes what Mr. Lenoir was saying, or what Jesse’s dad was saying, which is that Mrs. Parks really saw that there was no dividing line between what they were doing fighting racism here in the United States and the struggle against the war in Vietnam. Also, many activists, even in the ‘60s, let alone the ‘70s and ‘80s, like Mrs. Parks, began to look at other anti-colonial struggles on the continent and also the anti-apartheid struggles in South Africa. She was a long standing activist against apartheid and against U.S. investment in apartheid. Then, Deborah just put in the chat a photo of her. Like Mr. Lenoir was saying, there were these constant protests outside the South African Embassy, and so she’s there with those. And the picture is in the YA book and in the regular book. Hagopian: That’s so beautiful, to think about how Rosa helped spark this massive uprising in the U.S. and then sees how important it is to be part of the struggle internationally, is exactly, I think, what we were talking about to kick this whole session off. Thank you for sharing that. I have a couple more questions and maybe other people have questions that they want to throw in the chat, too. But I love seeing all these remembrances of where people were during the struggle and things they remember. Gil Scott Heron’s song “What’s the word? Johannesburg.” Lenoir: That song was quite an inspiration on the ground, both in the U.S. and in South Africa. Hagopian: What kind of car were you rolling in when you were bumping that? Lenoir: I had a hooptie, man. There was a song called “Free Nelson Mandela” by the Soweto singers that was also very popular at the time. “Free Nelson Mandela,” it was hyping us up, I tell you. Hagopian: Excellent. Yeah, and Miriam Makeba. Lenoir: Yes, Miriam. Hagopian: Someone said they have a friend named after her. And Sweet Honey in the Rock has called “Biko,” is that right? I haven’t heard that one. Lenoir: Oh yeah. Man, that was a very strong song, too. Yeah, “here comes Steven Biko.” Yep. Hagopian: Alright, excellent. Well, I have a couple questions and then maybe other people have some questions too. But I loved that people threw the playlist in there, because I think starting these lessons off in your classroom with the music could grab their attention, and then dissecting the lyrics and getting into the history might be a great way to introduce this in the classroom. I also think that we need to make this history relevant to our students’ lives today, so that it’s not just a history lesson, but it’s a guide to action today. So, I want to start with talking about why this is important to Black Lives Matter activists today, why the fight for racial justice here in the U.S. needs to know about the fight against apartheid in South Africa. Lenoir: Yeah, the Black Lives Matter movement is on it. The leaders in that movement, a lot of them have a consciousness of the struggle against racism and white supremacy that is international. One of the reasons is that Ayọ Tometi [formerly known as Opal Tometi], who, Jesse, you’ve met and worked with Ayọ Tometi. Hagopian: Ayọ wrote the foreword for the Black Lives Matter at School book. Thanks to you for introducing us. Lenoir: So Ayọ comes from a family of Nigerian immigrants. She was born and raised in Phoenix. I was the founding director of the Black Alliance for Just Immigration and hired Ayọ as our national organizer. When I left the organization in 2014, Ayọ became the executive director. She was one of the co-founders of Black Lives Matter and brought to that movement and into that grouping an understanding and a consciousness around pan-Africanism and the need to unite African Americans with our brothers and sisters across the diaspora, both in the U.S. and across the world. That is so critical to understanding. Ayọ is still working in the international realm to bring folks, particularly from the continent, into dialogue in struggle with folks in the U.S. Hagopian: It’s a new organization, Diaspora Rising, I believe it’s called. Is that right? Lenoir: That is right. If you go to diasporarising.org you can connect to her newsletter that comes out, and some of the work that she’s doing. There’s another group called Africans Rising, which is a network on the African continent across I don’t know how many countries that is doing work in linking the struggles on the African continent, in bringing to bear the weight of all of the activism on the continents on critical issues facing folks on the continent. Some of the folks from Black Lives Matter are also connected in that network. I think it’s really important that we confront an international system with an international organizing strategy. Really, the crux of it is the anti-Black racism in the world, that is the foundational relationship for white supremacy. I think it’s really critical for us to bring that to our students, for them to understand their connection to the continent, and to create a new pan-African identity. What is happening in this country is that the fastest growing part of the Black community is migration, particularly from the African continent and from the Caribbean, that’s creating friction within our communities because the powers that be are playing us one off against each other. For example, quote unquote, “affirmative action slots” are often given to African immigrants as a way to divide and conquer us, to drive a wedge between us. Same thing happened in corporate America. So, it’s really important for us to develop the kind of consciousness that says, “We’re in this, we have the same struggle against a system that has created colonialism and neocolonialism throughout the world and created systems of oppression in this country.” Part of the work that I was doing in the Black Alliance for Just Immigration and the Pan African Network was to foster that kind of pan-African identity through what we call African Diaspora Dialogues, where we bring people from the diaspora, from what we call the old diaspora — those of us whose ancestors were enslaved — and the new diaspora, the folks that came after us, trying to bring those groups together to create dialogues about what is it that’s dividing us? What is it that we can come together around? How do we create this new identity? Hagopian: I love that work that you have done for years, bringing together African immigrants with African American folks here, and even with border solidarity work with Mexican immigrants and Latinx immigrants. That’s such important solidarity work. Lenoir: I think we have a tendency to think that the struggle on the continent is over because colonialism has ended, but it’s far from over. Corporations are pillaging and plundering the countries of the African continent. It is our corporations and European corporations that are doing this, so we have a responsibility to make sure that we connect our struggles, because those same corporations are the ones that are oppressing us here in the U.S. I think we need to really look at that and understand those connections. Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. There’s uprisings that we can stand with, like in Nigeria, that are important to support. Lenoir: In Nigeria when George Floyd was murdered, they started demonstrations against their own police, against police brutality in Nigeria. And it really sparked a huge movement in Nigeria. Same thing in England, same thing in France. Hagopian: There’s so much good stuff going on in the chat, and I just want to highlight for people that we do have a lot of curriculum on teaching about South African apartheid, specifically, a lot of lessons that Bill Bigelow created. And maybe, Bill, if you’re there, if you want to just quickly say some of the resources that you would point people to. Bill Bigelow: Thanks, Jesse. Can you hear me okay? We have three pieces at the Zinn Education Project. One is a book I did that came out in 1985, called Strangers in Their Own Country, which became the main anti-apartheid curriculum that was distributed by TransAfrica and the American Committee on Africa. A lot of the Solidarity Movement was banned in South Africa. There’s still a lot of lessons in there, I think, that are valuable, including one that is really critical of the role that U.S. investment played in South Africa. One of the things I think that is important to remember is that there is no alignment between U.S. investment and progress, that the worst years of repression in South Africa also saw the greatest amount of U.S. direct investment in South Africa. Those lined up. So there’s that book that you might take a look at. Someone also in the chat mentioned the wonderful video, Sun City, which is also really worth using with students, not just because it’s a great song, but here are musicians that came together from around the United States — really around the world, there were South African musicians as well — at great risk, to say, “Don’t play Sun City.” Sun City was a place in the so-called homeland, that South Africa was using to say, look, you can come here, it’s integrated, it’s all fine and wonderful, and to offer legitimacy to the system of apartheid. Even Tina Turner, played, and Rod Stewart. They were attracting all kinds of big names. And once Little Stephen and Bruce Springsteen and Run DMC and so many others participated in this video to boycott Sun City, people stopped. It was a very, very effective gesture. And then finally, there’s an activity booklet on the film Witness to Apartheid that includes a roleplay on student activism in South Africa. I see that Mr. Lenoir is back with us, and so I won’t take up any more time. But thanks for giving me an opportunity to share those resources, Jesse. Hagopian: Yeah, that worked out because I’m really glad you could share all those great resources. Everybody should check those out, for sure. I’m glad you found a computer that’s working. Lenoir: I had to switch computers. Hagopian: No worries. I have a last question that I think is really critical for us to grapple with today in terms of the importance of the movement against apartheid in South Africa, and that’s the movement against apartheid in Palestine. Human Rights Watch just released a report calling it apartheid. This shirt that I’m wearing right now is not from the South African struggle, I got this shirt in the West Bank. You and I went on a trip in 2011. It was a civil rights delegation and we had veterans of the Civil Rights Movement who were going to learn about the parallels to struggles in the U.S. and South Africa and learn more about the struggle. So, I wonder if you can talk about the importance of understanding what’s happening in Palestine and the parallels to South Africa? Lenoir: Yeah. As you said, Jesse, I’ve been there twice, once in 2008 and then when I led this delegation that you were on in 2011. It was really striking to me the similarities between the systems in Palestine, in Israel, and in South Africa. The dispossession of land, taking the best land, the pass system. I was on a public bus with some of the folks and we witnessed guards who got on the bus with semi-automatic rifles, three of them approaching every Palestinian on the bus and asking for their papers. One of the Palestinians apparently did not have the right papers so they took him off the bus. The guide that was with us said he could be released the next day, a week from now, a month from now, a year from now. Nobody knows once you get arrested, you don’t know what’s going to happen. We witnessed people lining up through metal detectors to get into the city to go to work, to Jerusalem to go to work. I witnessed in Hebron one of the Palestinian attorneys who we were meeting get accosted, again, by an Israeli soldier with a semi-automatic rifle because he knew that he was an activist. I watched this very tense exchange between the two of them, and we believe that the only reason why it didn’t escalate is because there was a crew from I believe Sweden who was filming the whole encounter. I was in Hebron and saw the apartments that were taken over by Israeli settlers, and went through the market there, above the market where the Palestinians were selling their wares, in the market above them was the apartments that they used to live in and they had a netting across the top of it because the Israeli settlers would throw garbage down on the Palestinians. Hagopian: That was one of the most shocking parts of the trip for me, when we went and saw from the Israeli settlers point of view and heard their tour that they gave us and then we went below and we saw this net that was covering up this row of shops and heard about how they would throw garbage and then acid. I’ll never forget that. Lenoir: It is not an exaggeration that apartheid lives in Israel and Palestine. The settlements in the West Bank are there to try to make the two state solution impossible. They continue to grow. I stayed in a village called Baleen, where the Israeli government had walled off the vineyards that the Palestinians work in to make a living, had walled it off and created a wall. There was one entrance in and out of this village, they sealed off all the rest of it. Above the village is where the Israeli settlers were, so that they can look down the village and have a vantage point if any trouble started. The apartheid roads, there were some roads that if you had the wrong license plate, if you had Palestinian license plate, then you could not be on that road. You would be arrested immediately for traveling on that road. The parallels with the wall, a huge wall. That wall snakes through and does not comport to the boundaries that were settled in terms of where the Palestinian state would be. What it does follow is where the water is. They blocked off water resources from Palestinian villages. The national cry is beginning to bubble up now, and this has been a longtime struggle. SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, passed a resolution in support of Palestinian rights in the ‘60s. Similarly, members of Black Lives Matter also made trips to Palestine, creating solidarity groups in support of Palestinian human rights. It’s really critical that we understand the way that Palestine resembles South Africa. In fact, during the anti-apartheid era, Israel was one of the apartheid regimes’ greatest allies. They helped them get nuclear capability. They provided them with arms and training, and it continues. Hagopian: Thank you. Unfortunately, we’re going to have to wrap this conversation up. I really appreciate the time. You getting to share all this with everybody else is special for me. I dropped a link in the chat to an interview I did with Aaron Dixon about how the Black Panther Party supported Palestine and Palestinian liberation. There’s also this awesome new children’s or young adult book called Determined to Stay: Palestinian Youth Fight for Their Village that makes the connection with Black struggle here at home for youth to see that I’d recommend educators use to introduce this topic and the connections to Palestine. So thank you everybody for being here. We have an evaluation link that we hope you will all take the time right now to click on. If you can click on that, I’d be grateful if you can start to fill out that form. If you want to unmute yourself and say thank you to my dad, that will be awesome. All: Thank you. Lenoir: Thank you for the opportunity to be with my son. I enjoyed it. And I hope you all bring these lessons into the classroom. It’s so important. Jesse, one quick thing. I was at a party in Detroit with a bunch of people from Seattle, [and there was] this young man from Seattle, a young Black man who had written his thesis on South Africa. I said, “Do you know anything about the anti-apartheid movement in Seattle?” He’d never heard of it. We’re losing our history and we need to bring it to the classroom. I appreciate all of you for doing that. While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Transcript

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Additional Resources

Here are many of the resources recommended by the presenters and also by participants.

Lessons and Curricula |

||

|

Witness to Apartheid: A Teaching Guide by Bill Bigelow Sun City – A Teaching Guide by Bill Bigelow How to Make Amends: A Lesson on Reparations by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca Strangers In Their Own Country: A Curriculum Guide on South Africa by Bill Bigelow |

|

Related Books and Article |

||

|

|

Ruth First and Joe Slovo in the War Against Apartheid by Alan Wielder Chain of Fire by Beverley Naidoo Journey to Jo’burg: A South African Story by Beverly Naidoo Madiba A to Z: The Many Faces of Nelson Mandela by Danny Schechter Nelson Mandela: The Authorized Comic Book by Umlando Wezithombe No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950-2000 edited by William Minter, “Fists of Freedom: An Olympic Story Not Taught in School” by Dave Zirin |

Films |

||

|

||

This Day In History |

||

|

June 16, 1976: Soweto Uprising |

||

Music

“Biko” by Sweet Honey in the Rock

“Free Nelson Mandela” by Soweto Singer

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

I didn’t know that the rebellion in Soweto in 1976 was connected to language in schools. I also found the point about the longshoremen not unloading the ships to be inspiring.

I loved the way that Mr. Lenoir emphasized the role of students doing the steady work of showing up every week, in their own city, and how groups of students and other regular people all around the country and the world were able to accomplish their goal!

People fought so hard for Black Studies in schools.

Personal stories are history in the moment. Tell your stories. It inspires others. Don’t lose your history.

The expansiveness of the anti-apartheid struggle in the United States.

Freedom struggles are all tied together. Apartheid, Palestine, white supremacy are all dimensions of the same issue!

Reinforced the importance of making connections between the different freedom struggles throughout the world.

I think the most interesting thing I learned was connecting the South African apartheid laws to what is actively going on between Israel and Palestine. I never thought about doing this, but it would be perfect since I teach both of these topics back to back.

The power of transnational student activism and the framing of Black liberation as an international struggle against white supremacy around the world.

The actions taken on the ground in the U.S. to support the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa.

It was great to be reminded of these years and events to get an intimate first-hand perspective, and to connect that struggle and those tactics with today’s world and current social justice issues.

Honestly, just hearing testimony was critical. Mr. Lenoir’s stories made me remember where I was during all the fights of the 70s. I wonder what stories my students will recall in 40 years.

Reminder to interconnect the struggles across the world for students. We can learn how to address egregious issues in our own country from these international lessons.

The parallels between BLM, the anti-apartheid movement, and the uprisings for Palestinian liberation.

Existence of Black Alliance for Just Immigration because I’m looking it up to support such work.

What will you do with what you learned?

Today’s class will help me share deeper connections between the colonialism in South Africa and that in Palestine.

Will dive into Bigelow’s teaching resource (it was shared in the chat), and help students see the connections between Jim Crow laws and apartheid in South Africa.

1) I’m sending the picture of Rosa Parks to my students who wrote about her this year. 2) This information continues to build my understanding of how people are working for justice. I stand in awe.

I will try to learn more about the international approach — boycotts, etc.

It will inform my work with pre-service and in-service educators.

I have taught about South African apartheid before, but I really want to focus more of my own study to it so that I can do it more justice. I want to spend more time delving into it and the transnational connections.

This informs my organizing and engagement in groups here in the United States, particularly as it relates to the struggle for Palestinian liberation and the fight against Israeli apartheid.

I didn’t quite realize the direct connections between the movement for Black Studies in universities and the anti-Apartheid movement. I teach in Ithaca, NY, where we had a really powerful Black student movement (Willard Straight Hall Takeover at Cornell University). I am excited to look into the anti-Apartheid activism at Cornell, but also at the school where I teach. I bet that we had a student group, and I am thinking maybe we could even do some primary source research into our school’s old yearbooks to find out. These sorts of connections really help to not only bring history to life for my students, but to help them see that they can have a meaningful role in movements for justice today.

I am working on how to teach social justice through French. Someone in my breakout room shared resources that I will look at this summer. In the short term, I’ll tell my students these stories.

I use MANY resources from the Zinn Education Project — and will use even more. We “owe” Howard Zinn, Bill Bigelow, and Mr. Lenoir for their information and inspiration. Thank you.

I will do my work to help my students connect the dots between economics and the global nature of white supremacy. I will also share stories of children and young adults that battled oppression and provide opportunities for students to be organizers in their communities.

What did you think of the format?

It was a beautiful discussion and I felt honored to be in the space. I enjoyed the breakout rooms as a space for a small conversation. It was very well timed, the whole format was well timed. I could have stayed in the main room all afternoon and evening, though.

The combination of a large scale webinar and breakout rooms worked.

My breakout group had a Native woman from MN; it was great to get her perspective, as well as the contributions of two women who teach incarcerated folks. More time for breakouts in the future.

The breakout room was great. Loved that Jesse could be in dialogue with his father!! Family of organizers and freedom fighters. The connections were strongly lived and felt.

I so appreciated all aspects of today’s event. Thank you to everyone who facilitated, emceed, and contributed. Thank you to Mr. Lenoir. This was the first time I attended one of these events, and to hear from people whose works I have followed and read for years was very inspiring and humbling. Thank you.

I appreciated the sign language interpreter, even though I do not know sign language. Of the many pandemic webinars I have attended, I have never seen that service offered.

All worked well. There is always a desire to spend even more time in a Breakout Room with like-minded educators — sharing, listening, and learning.

I wasn’t able to participate in the breakout room because I was on a call, but I like that the time was organized the way it was.

Miigwetch for the ASL signers. I don’t use the chat much when the speaker is talking. It distracts me from listening. I do check for the links shared from ZEP. Plus the Elders say to listen when someone is talking, especially when they are older.

Additional Comments

Good combination of content and spirit.

Thank you for the additional information on Palestine.

We need to go to the next level — student activism groups, national coordination. We appreciate ZEP leadership. Thank you!

Thank you for continuing to have this type of programs on Zoom!

In general, I would love to see ZEP expand into more international issues — I teach global history, particularly of the Atlantic World, and I would love to see (or even collaborate on creating?) some more resources that go beyond the US!

I find these opportunities very valuable — always leads to making additions/changes to my courses. Thank you.

Miigwetch for offering this series.

Presenters

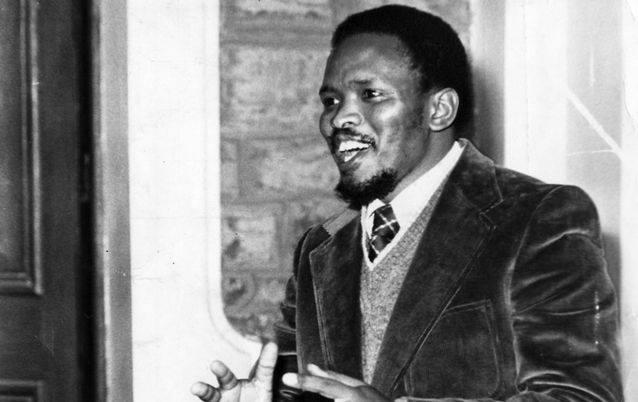

Gerald Lenoir is an analyst at the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society with a long history of organizing and activism. Among other roles and accomplishments, he was the Executive Director of the San Francisco Black Coalition on AIDS (1989 – 1995). Lenoir co-founded the HIV Education and Prevention Project of Alameda County, co-founded Priority Africa Network in 2003, and has served on the board of the National Network for Immigrant and Refugee Rights since 2006. He is a former board member of the Interfaith Peace Builders and led its first African Heritage Delegation to Palestine/Israel in 2012. Lenoir is also a writer, his latest book being a collection of poetry about police violence: United States of Struggle: Police Murder in America.

Jesse Hagopian teaches Ethnic Studies and is the co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, and editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn