By Bill Bigelow

In the Epilogue to his book How the Word Is Passed, Clint Smith writes:

The history of slavery is the history of the United States. It was not peripheral to our founding; it was central to it. It is not irrelevant to our contemporary society; it created it. This history is in our soil, it is in our policies, and it must, too, be in our memories.

And one of the ways this foundational history enters our memories is through the classroom. This is work for all of us — to create, to share, to teach. Below are some discussion and writing questions, as well as a few possible activities, that can take students more deeply into Smith’s brilliant book. As Smith suggests, one cannot understand the history of the United States without focusing on the centrality of slavery — and this history is essential to helping our students make sense of the world around them.

How the Word Is Passed arrives at a moment when Republican legislators in at least 27 states are offering the country a lesson in How the Word Is Suppressed. Proposed legislation takes aim at a host of curricular initiatives, approaches to understanding society (e.g., Critical Race Theory), and organizations — including in Missouri’s House Bill 952, which would ban use of Zinn Education Project materials in all of the state’s schools. What unites these measures is a determination to keep students away from studying how slavery and exploitation based on race are fundamental to thinking intelligently about our lives today.

Teaching an accurate, honest, critical history is an act of resistance to these initiatives. As the Zinn Education Project’s “Pledge to Teach the Truth” insists: “From police violence, to the prison system, to the wealth gap, to maternal mortality rates, to housing, to education and beyond, the major institutions and systems of our country are deeply infected with anti-Blackness and its intersection with other forms of oppression. To not acknowledge this and help students understand the roots of U.S. racism is to deceive them — not educate them.”

The Pledge concludes: “We will continue our commitment to develop critical thinking that supports students to better understand problems in our society, and to develop collective solutions to those problems. We are for truth-telling and uplifting the power of organizing and solidarity that move us toward a more just society.”

Clint Smith’s How the Word Is Passed can play an important role in that truth-telling. I hope these questions and suggested activities can help connect students to the critical wisdom contained in this book.

Discussion and Writing Questions

- When and where was the largest revolt of enslaved people prior to the Civil War? If you have a hard time answering that question, why? What does it say about our curriculum, about what matters in the U.S. history curriculum, that this is such a difficult question to answer?

- On p. 58, Clint Smith quotes the Rev. William J. Barber II: “The same land that held people captive through slavery is now holding people captive through this environmental injustice and devastation.” What does the Rev. Barber mean by this? Why would environmental injustice be happening to the descendants of people who were held in slavery, in the very same places where people were enslaved?

- Yvonne Holden is the director of operations at the Whitney Plantation. While leading Clint Smith on a tour of the Whitney Plantation, she said that when she visited the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, she started to understand “exactly what legacies are. They’re not just the things we choose. A lot of them are the things that we don’t choose. So that also made me realize exactly how close my family is to this history.” What does the word legacy mean? How does the legacy of slavery live in you? How does it live in your community?

- John Cummings, the founder of the Whitney Plantation, outside of New Orleans, read the narratives of formerly enslaved people and asked himself: “How could this have happened and I didn’t know about it?” How would you answer Cummings’ question?

- Reflecting on his time at the Whitney Plantation, Clint Smith writes, “I thought of how I had grown up in Louisiana and never been taught that the largest slave rebellion in U.S. history happened just miles from the city that had raised me. I had never been taught that the Louisiana Purchase was a direct result of the Haitian Revolution, the uprising that laid the groundwork for all the slave revolts that followed in its wake.” (p. 84) Finish this sentence: “I had grown up in . . . And never been taught. . . .” And even if you still haven’t been taught it, what things do you have inklings of that you want or need to know?

- About Angola State Prison, Clint Smith writes, “I think of all the ways this country attempts to smother conversations about how its past has shaped its present.” (p. 101) What does that mean? Where else do you see attempts to smother conversations about how our past has shaped our present?

- Why is it significant that Angola used to be a plantation? What’s the connection between slavery and today’s over-incarceration of Black people?

- Angola State Prison, with an overwhelmingly Black prison population, is built on a former plantation that relied on enslaved Black workers. Clint Smith writes, “If in Germany today there were a prison built on top of a former concentration camp, and that prison disproportionately incarcerated Jewish people, it would rightly provoke outrage throughout the world.” (p. 101) Why in the United States is the outrage “relatively muted,” as Smith points out?

- Paul C. Gramling Jr., the commander in chief of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, was the keynote speaker when Clint Smith visited Blandford Cemetery for its Memorial Day commemoration of the Confederate soldiers buried there. Predict some of the things that you think Gramling will say.

- During his time at Blandford Cemetery, Smith talks with Jeff. Jeff told Smith that he had 78 family members buried in the cemetery dating back to 1802. How can Jeff make sense of his “heritage” in a way that recognizes the horrors of slavery? How can he learn the truth about slavery and what the Confederacy stood for and come to grips with his family history?

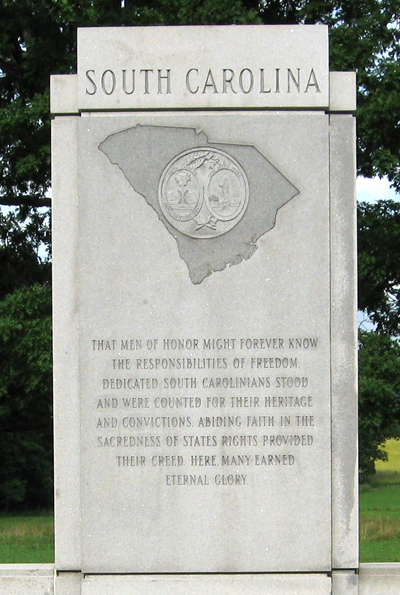

- Another man Smith talks to at Blandford Cemetery is Jason. Jason is 48 years old and has read extensively about the Civil War. He tells Smith that he is more sympathetic to the South, and when Smith asks whether or not he thinks that the secession of Southern states was tied to slavery, he says, “No.” He explains why he believes Southern soldiers were not fighting to preserve slavery: “The average age was 17 to 22 for a Civil War soldier. Many of them had never even seen a Black man. The rich were the ones who had slaves. They didn’t have to fight. They were draft exempt. So these men are going to be out here and they’re going to be laying down their lives and fighting and going through the hell of camp life, the lice, the rats and everything else just so this rich dude in Richmond, Virginia, or Atlanta, Georgia, or Memphis, Tennessee, can have some slaves. That doesn’t make sense. To me it’s common sense. No man would do that.” (p. 168) Write a response to Jason’s comments.

- Smith writes that, “Greg Stewart, a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, told the New York Times in the aftermath of the 2015 Charleston Massacre, ‘You’re asking me to agree that my great-grandparent and great-great-grandparents were monsters.’” (p. 172) Is that what Clint Smith is demanding of all those who have Confederate ancestors buried at Blandford Cemetery? Explain.

- Clint Smith writes: “In 1863, when the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, Black Americans owned only 0.5 percent of the total wealth in the United States. Today, that number has barely increased: Black people own about 1-1.5 percent of the nation’s wealth. Despite the role Black Americans played in generating this country’s wealth, they don’t have access to the vast majority of it.” (p. 192 – 193) Use what you know about racism in U.S. history to explain how so little has changed in terms of wealth distribution in more than 150 years since the Emancipation Proclamation.

- New York City has been a center of banking in the United States. What role might these banks have played in the system of slavery? What might banks have financed for enslavers? If there are banks today that have their origins in slavery and profited from slavery, what obligations do these banks have today to the descendants of people who lived in slavery?

- How the Word Is Passed focuses mostly on sites where slavery is remembered and misremembered. What sites would you choose if the purpose of the book were to focus exclusively on resistance to slavery?

- United States History is a typical mainstream textbook, produced by the giant educational publishing company, Pearson. The book presents a positive portrait of Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson makes things happen; his life is verb-rich. He writes (the Declaration of Independence); he assumes (the presidency); he considers (joining the British in an alliance to fight France); he reasons (to avoid war by purchasing New Orleans); he decides (to purchase Louisiana Territory); he acquires (this territory); he sends (Lewis and Clark to explore the new lands). Jefferson is “wealthy, refined, and educated.” And he was against slavery: “During the 1780s, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and George Washington hoped that slavery would gradually fade away.”

But in his chapter on Monticello, Jefferson’s estate, Clint Smith presents a different version of Jefferson. Smith records one visitor to Monticello who reflects on how everything Jefferson did depended on the people he enslaved: “From the moment he [Jefferson] got up in the morning till the moment he went to bed at night, he’s relying on slave labor for every aspect.”

Based on Clint Smith’s discussion of Monticello, ask students to create a textbook entry about Jefferson that reflects the role of enslaved people in Jefferson’s life and work — “from the moment he got up . . . till the moment he went to bed. . .” Textbooks leave enslaved people invisible in the lives of U.S. presidents. See Clint Smith’s classroom-friendly PBS clip, “Why we shouldn’t forget that U.S. presidents owned slaves.”

- In his chapter about Gorée Island in Senegal, Clint Smith writes: “Memory, for me, is often a home where the furniture has been rearranged one too many times.” (p. 239) What is a metaphor that describes memory for you?

- In downtown Dakar, Senegal, Smith walks with journalist Momar Niang, who says, “I’ve never been to the slave house before.” Smith writes that Momar’s “voice was coated with the texture of cigarette smoke. I turned my head toward him as we stopped on the curb of the street before crossing. ‘I guess it was shameful for me,’ he added.” (p. 240) What does the word “shame” mean to you? Should anyone alive feel shame for slavery? Why or why not? Why do you think that Momar, who is Senegalese, indicates that a site for the slave trade would be a source of “shame”

- How do you think Senegalese schools might teach slavery differently than it’s taught in U.S. schools?

- Clint Smith thought back to all of the times that he had heard his own students ask, “But why didn’t they fight back?” (p. 247) How would you respond to that student question?

- A question that often gets asked is: How could one group of people enslave and brutalize another group of people? Clint Smith talks to Eloi Coly, curator and site manager at the House of Slaves on Gorée Island, who offers his answer to that question. Smith writes: “As the desire for enslaved people increased, Europeans had to justify the human plunder. In order to rationalize taking a person from their home, separating them from their family, and shipping them across an ocean to work in a system of intergenerational bondage, Eloi said, these Europeans could not see these Africans as people. ‘They considered Black Africans not as human beings, but as a simple merchandise. If they consider Africans as merchandise, that is because they understand the necessity to dehumanize Africans in order to work for the acceptance by all the Europeans. The necessity to use Africans because Africans are not human beings.’” Put this passage in your own words. Do you agree with Eloi Coly? Explain why or why not.

- Write the apology the U.S. government should make to the descendants of those formerly enslaved or to African countries. Or choose a descendant of a former enslaver. Word their apology to descendants of those enslaved by their ancestors. [Teachers: See “Sorry Not Sorry,” by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (Rethinking Schools magazine, Summer 2018), on teaching about genuine and hollow apologies in history, and the significance of authentic apologies.]

- In his Epilogue (on pages 273 and 279), Clint Smith includes two pieces about his grandparents:

The year my grandfather was born, a gallon of gas was twenty cents and a loaf of bread was nine. Slavery had ended six decades ago, and twelve years later everyone would forget. The year my grandfather was born, he had eight siblings and two parents and a grandfather born into bondage he tried to bury. The year my grandfather was born, millions of Americans were unemployed and over a thousand banks shut down. The Great Depression had taken a deep breath, and the US didn’t exhale for years. The year my grandfather was born, twenty-one people were lynched and no one heard a sound. The trees died and the soil turned over and the leaves baptized all that was left behind. The year my grandfather was born, there were full trains leaving Mississippi, and only empty ones coming back.

The year my grandmother was born, the Florida Panhandle was burning hot with white terror. Black children were taught to keep their eyes down, their mouths shut, and to make it home before the sun dissolved behind the trees. The year my grandmother was born, the country was on the cusp of entering a war being fought across two oceans. Black men would be sent to fight for freedom and come back to a land where they didn’t have their own. The year my grandmother was born, she was held in her mother’s arms and had no way of knowing how soon that embrace would disappear and never return, how soon her mother’s face would become something she couldn’t remember. The year my grandmother was born, there were laws that wrapped themselves around the necks of everyone she knew, and no one knew if they would let go.

Pick a parent, grandparent, or other relative or family member — they needn’t be biological relatives — and use Clint Smith’s pieces about his grandparents as a model. Write about the year someone was born, or when something key happened in their life — for example, “The year my grandfather got married…” Note how Smith is alert in both his pieces to racial inequality and violence, to economic hardship, but also to personal dimensions: “my grandmother . . . was held in her mother’s arms and had no way of knowing how soon that embrace would disappear . . .” Try to incorporate all these into your piece.

- Clint Smith describes what his grandmother’s voice sounds and feels like to him: “Her voice is the front porch of a home with everyone you love waiting inside.” Think about that home for you, with “everyone you love waiting inside.” Who is inside?

- When Clint Smith talks with his grandmother, he writes, “I asked her directly, hypothetically, if she had the chance, what she might have wanted to know from [her grandfather]” (p. 280) — a man who was born just five years after the end of slavery, but in times “that didn’t feel that different from slavery.” Imagine you had relatives who had lived during slavery, what questions would you have wanted to ask them? What would you want to know? Or, you might answer this about any relative who lived during the period of slavery, even if they would not have been enslaved.

- When Clint Smith’s grandmother visits the National Museum of African American History and Culture, she says, “I lived it.” At the top of p. 288, Smith begins a poetic passage with the refrain, “When my grandmother said, ‘I lived it,’ what I heard was. . .” Imagine an individual whose life was shaped by living in slavery or the Jim Crow era. Use Smith’s repetition of “When . . . said, ‘I lived it,’ what I heard was. . .”

- Smith writes, “My grandparents’ stories are my inheritance; each one an heirloom I carry.” (p. 288) Imagine that one of the stories from How the Word Is Passed is an object, “an heirloom.” What does it look like? How does it feel? Why is it important? Draw it.

- Smith writes, “I think of how decades of racial violence have shaped everything we see . . .” (p. 288) What are those things in today’s society that were shaped by decades of racial violence?

- Smith says that slavery is “a crime that is still unfolding.” (p. 289) What does he mean by that?

- Smith offers the thesis of an essay: “The history of slavery is the history of the United States. It was not peripheral to our founding; it was central to it. It is not irrelevant to our contemporary society; it created it. This history is in our soil, it is in our policies, and it must, too, be in our memories.” (p. 289) Provide evidence to support this thesis.

Suggested Activities

- Read aloud beginning on p. 95, with “Upon approaching the building where executions took place. . .” through p. 98, ending with “. . . the bus’s rubber tires spit out clouds of dust behind them.” As students read, have them mark passages, lines, words that they find significant or powerful. Afterwards, have students do a read-aloud choral poem with parts of the reading they highlighted.

- One of the frequently heard reasons for the secession of Southern states from the Union in 1860 and 1861 was that they were motivated by a commitment to “States rights.” Read the excerpts from secession documents included on pages 151 to 154 and then find a textbook that misrepresents the actual cause for Southern secession. Critique this textbook’s treatment of secession.

- As part of the Juneteenth commemoration on Galveston Island, Texas, Smith describes how student after student came up and read details about the history of slavery from Columbus’s arrival in 1492 up through June 19, 1865 — Juneteenth, the day when, on the balcony of Ashton Villa in Galveston, Union General Gordon Granger is said to have read aloud the order that proclaimed the end of slavery. Divide the class into small groups and assign each group a time period — e.g., 1492 to 1600, 1600–1650, 1650–1700, 1700–1750, 1750–1800, 1800–1825, 1825–1850, 1850–June 19, 1865. Ask each group to come up with key dates about slavery and the resistance to slavery that occurred during the period they are assigned. Create an event like the one in Galveston, with students presenting their chronology of slavery leading to Juneteenth.

- Clint Smith writes: “People sometimes believe that if they talk to Black youth about the historical legacy of slavery — and the intergenerational iterations of systemic racism that followed — young people will feel overwhelmed and shut down. But there is an enormous value in providing young people with the language, the history, and the framework to identify why their society looks the way that it does. Understanding that none of this was done by accident but by design. That did not strip me of agency, it gave agency back to me. I watched these young people share this history, and I dreamed of what it might mean if we could extend these lessons to every child. How different might our country look if all of us fully understood what had happened here?” (p. 179) Ask students in class to write a one or two sentence “answer” to Clint Smith’s question: “How different might our country look if all of us fully understood what has happened here?” Do this as a read-around, with every student sharing their responses to this question.

- Ask students to make a list of all the Europeans they can name who lived before 1900. Then have them make a list of all the Africans they can name who lived before 1900. Ask them to account for the discrepancy. Read them the Clint Smith quote: “In my experience — as both educator and student, as researcher and writer — there was little mainstream discussion of who Black people were before they reached the coasts of the New World, beyond the balls and chains.” Ask: Is that true for your schooling as well? If so, why do you think that is? Why is there such little attention paid to life in Africa at the time of and prior to the slave trade?

- A question for ourselves as teachers: When Clint Smith is with Momar Niang on Gorée Island, Momar says, “And I was just searching myself, at the place of those who have suffered. . . . I was putting myself back in the 17th century. I was trying to imagine on how we can treat the human being like this, and how we can pack so many people in such small places. And all around it’s like I can feel the pain myself.” (p. 258) How do we help students “search” themselves for how they can connect with those who suffered — and come to grips with how some people could dehumanize another group of people in this way?

Bill Bigelow is the curriculum editor of Rethinking Schools and co-director of the Zinn Education Project. These questions and teaching ideas are part of a suite of activities being developed to accompany How the Word Is Passed by a Zinn Education Project curriculum collective, which also includes Jesse Hagopian, Cierra Kaler-Jones, Ana Rosado, and Ursula Wolfe-Rocca.

Lessons

The Zinn Education Project team has prepared the following lessons to use alongside How the Word Is Passed. Echoes of Enslavement is online and the other two will be posted soon.

Echoes of Enslavement — Not Only in the South, but Everywhere

As a full class, students brainstorm dozens of different “echoes of enslavement” in their own state — discrete sites of remembering and forgetting, or worse — lies and distortion. Sites could be obvious — street and school names, burial grounds, monuments and statues — or less obvious: racially segregated neighborhoods, disproportionately Black prison populations, or the chapter on slavery in their district-adopted textbooks.

Once the class has a lengthy and fulsome list, students select one “echo” to learn more about through some independent investigation. Next, the class reads one chapter (or excerpt) from How the Word Is Passed to “raise the bones” — that is, identify how Smith creates such a compelling analysis so that students can emulate those strategies in their own essays. For example, students identify how Smith uses physical description with lots of sensory details, historical background, interior monologue, dialogue with individuals about the place, quotations from primary sources, etc. Access lesson.

How We Remember: The Struggle Over Slavery in Public Spaces

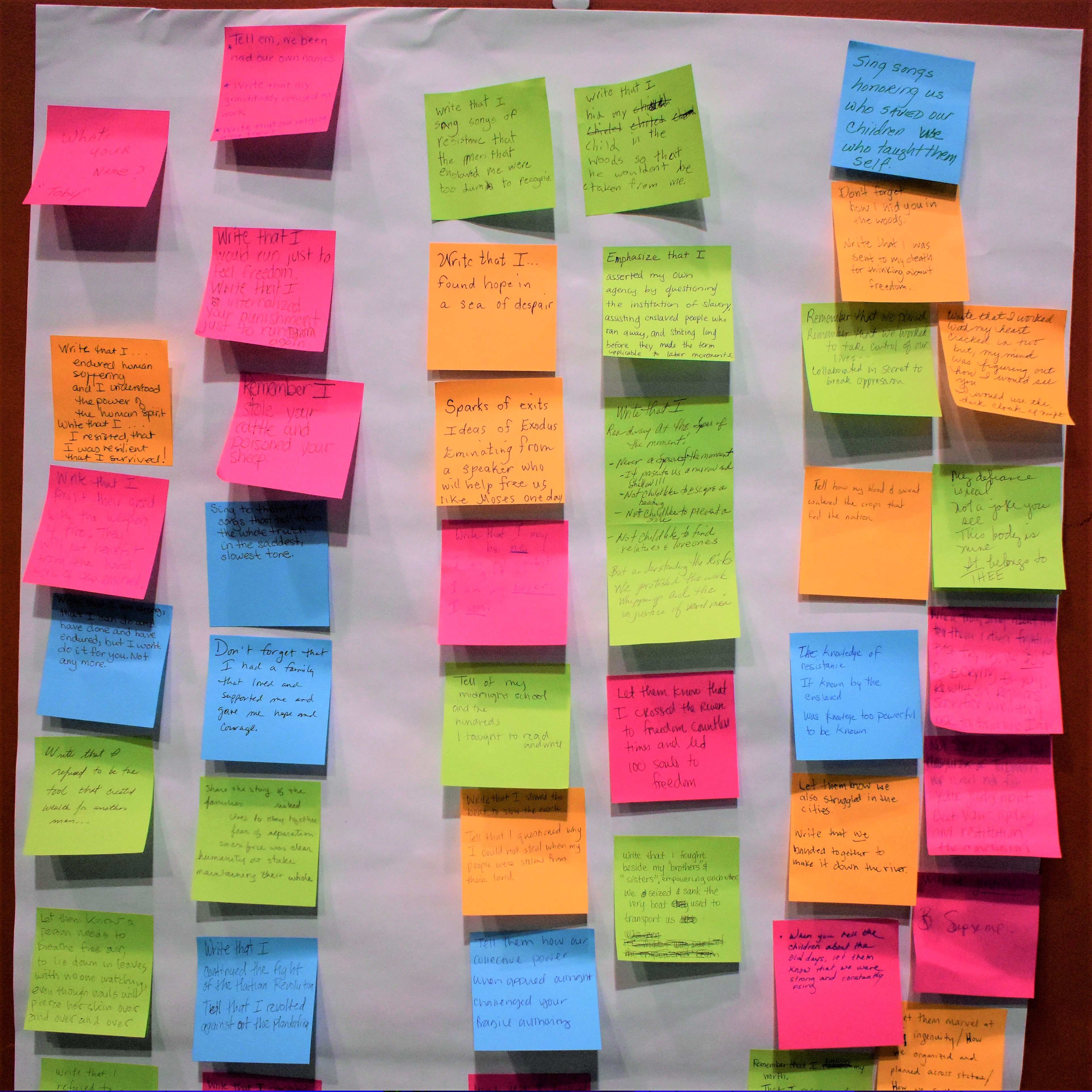

Students are assigned one of the eight sites from the book and receive fact sheets exploring what happened there with regard to the history of enslavement. The fact sheets include many quotations and details from Smith’s chapter on the place. Students then work collaboratively to design some kind of commemoration — a memorial, monument, museum, tour, etc. — with guiding questions:

-

- How might this site be memorialized? (If you were doing a tour, what would you show? What would visitors see, read, hear, experience? What images and art are used? How would you engage people?)

- What do you want visitors to feel, think, or do after they leave this site?

- How might others use this site to distort history? Or who might disagree with your memorial and why?

After designing and sharing, students see what actual choices were made and analyze differences between their choices and those made by the designers of the actual monuments or memorials. Access lesson.

Oral History

Students interview someone in their lives to create something based on that conversation. These interviews can turn classrooms themselves into sites of remembering. Build project parameters around Smith’s “We learn this history from . . .” list on p. 290 to combat Eurocentric modes of knowledge production and encourage students to embrace different ways of knowing, different sources of knowledge, different kinds of remembering. Students use Smith’s italicized grandfather and grandmother “poems” on pp. 273 and 279 as inspiration for what they might “create” based on their own family or close history. Access lesson.

Classroom Story

As a public historian, I was excited to use Clint Smith’s How the Word Is Passed in my African American History class in the fall semester. I assigned one chapter to each student to “become the expert” and teach the rest of the class about the historic site and its interpretation of African American history.

We used some of the discussion questions on the Zinn Education Project website as a starting point for our in-class discussion. Each student then prepared a poster for our university research colloquium, where they discussed the issues of interpretation of African American history with other faculty and students on our campus. In fact, one of the students took first place in the Humanities poster competition!

I had planned to use Smith’s book in my Museum Studies class this semester, but most of those students were in the class last semester and were already familiar with the book! As many of my students plan to become teachers, I’m happy for the opportunity to continue to remind them that “African American history is American history.”

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn