Close to 300 educators attended the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle class on Feb. 15 to learn about a new collection of Julian Bond’s lectures on the Civil Rights Movement (Time to Teach) and the long history of the voting rights struggle that led to the recent electoral victory in Georgia. This online class featured a conversation with SNCC veteran Judy Richardson, the co-editors of Julian Bond’s Time to Teach: A History of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, Jeanne Theoharis and Pamela Horowitz, and high school teacher and Rethinking Schools editor Jesse Hagopian.

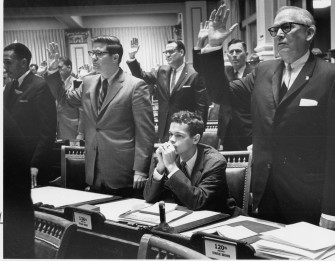

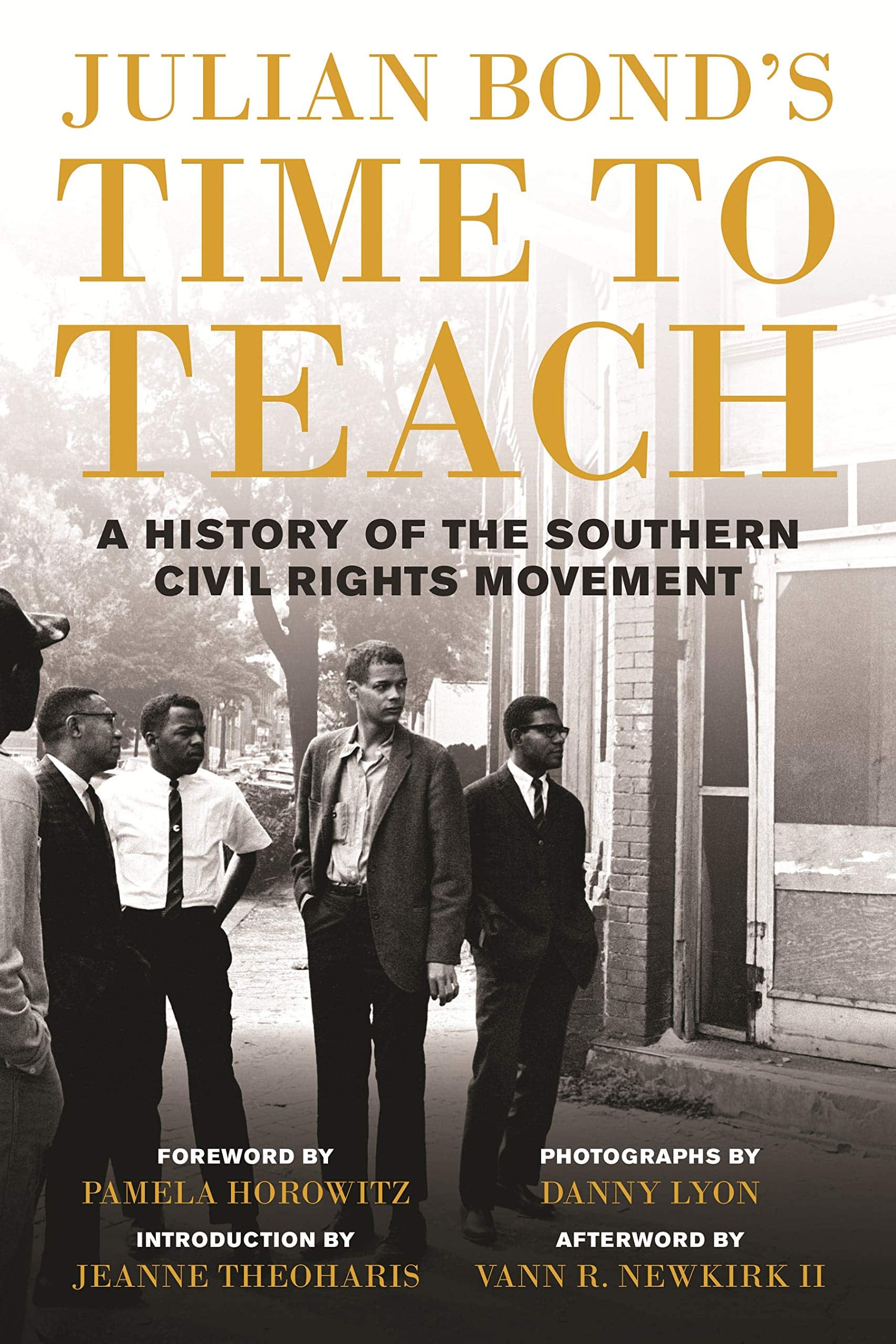

The featured book, Julian Bond’s Time to Teach, is a history of the Southern Civil Rights Movement as SNCC veteran and university professor Julian Bond (1940 – 2015) taught it for two decades, compiled from his teaching lectures. Bond had his own voting rights struggle in Georgia when the State House of Representatives refused to seat him as a state representative due to his public statements against the Vietnam War.

The featured book, Julian Bond’s Time to Teach, is a history of the Southern Civil Rights Movement as SNCC veteran and university professor Julian Bond (1940 – 2015) taught it for two decades, compiled from his teaching lectures. Bond had his own voting rights struggle in Georgia when the State House of Representatives refused to seat him as a state representative due to his public statements against the Vietnam War.

Here are a few reactions from the participants:

I learned that the Civil Rights Movement was not just popular historical figures like MLK, it was made up by students like me. I am still in college and I think for the first time I realized that the Civil Rights Movement was so much more complicated than I thought.

I was already familiar with Judy Richardson and her work with SNCC, but this was my first opportunity to hear her speak live and she blew me away!

It is important to record our movements to teach the next generation. The class spoke to the cultural power of passing down our stories.

I appreciate that after each of these sessions, I have a broader understanding of the depth of the Civil Rights Movement.

The day-to-day routines & interactions at my current school can tear me down and make me feel really weak, but woo-hoo — tonight I’m feeling a recharge!

Below, find highlights of the session, a full video recording, recommended resources, and more participant feedback.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: Welcome everyone, on behalf of the Zinn Education Project for our class on Julian Bond and the Southern Civil Rights Movement. Some of you are joining us for the first time and some of you have participated in our spring series. It is a gift to be able to share this time together, and I just want to really thank everybody for being in this virtual community with us. There’s so much going on in our lives these days, this year, and it means a lot to us that you took the time to come and join us for this session.

My name is Jesse Hagopian. I’m a high school teacher, I’m an editor with Rethinking Schools, and I work with the Zinn Education Project on the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle campaign. Rethinking Schools coordinates the Zinn Education Project along with Teaching for Change. The Zinn Education Project is hosting this session today and offers free downloadable people’s history lessons. I hope many of you have already used them. I know I use them regularly in my classroom. They’re great, especially for middle and high school classrooms.

We are joined by ASL interpreters Krystal Butler and Tyriibah Royal. Thank you so much for being with us and making this space accessible. Before we begin our conversation, we want to find out who’s in the room and go through our plans for our time together. We are going to do a quick poll to find out how many teachers, librarians, educators, historians, parents, students, and others are in the room with us. Many of you actually play multiple roles, so if that’s the case, then just pick a primary one, and we will post the poll for you to respond to. All right.

Thank you very much to Cierra for helping run the polls and making this session work behind the scenes. I appreciate you. We’re starting to get our numbers in here, and it looks like we have a majority of educators, with the next biggest being teacher educators, and then we have students. Thank you to all the young folks who showed up today. You’re going to learn about the role of young people in the struggle today. Shout out to the librarians and historians here. That’s wonderful. Community and labor organizers 6%, primary family members 3%, and all you in the “other” category, thanks for showing up.

Throughout this session, we want you to use the chat box to post questions, comments, and resources that other educators can use in their classrooms, any ideas you have, and we will read your questions and our guests will try to respond after the breakout groups. We will do our best to answer as many questions as we can in our limited time together. We’ll do a short evaluation at the end as well, so please make sure you stay for the end so you can fill out that evaluation. We’d love to get your feedback. You can also continue the conversation on Twitter. We encourage you to share your learnings and insights using the hashtag #TeachBlackFreedomStruggle. We’re ready to dive into this session now. After about 25 minutes, we’ll pause so that you can meet each other and talk in small groups and share your thoughts with one another. Then we’ll come back and hear from our historians and organizers.

It is my honor to introduce you all to a veteran of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC, Judy Richardson is with us. Thank you so much for being here, Judy. It is wonderful to have you here. We also have the co-editors of the new book, Julian Bond’s Time to Teach: A History of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, with us here today, Jeanne Theoharis and Pamela Horowitz. Thank you all so much for being here with us today. Thank you, Judy. Judy has presented here before in this series on the history of SNCC and I think she’s attended almost every session with us. I really appreciate that. Jeanne is a historian and actually the originator of this whole online series class. So we appreciate everything you’ve brought to the Zinn Education Project. And she recently released the Young Readers Edition of her book on Rosa Parks that every educator needs to pick up to effectively teach the real story of Rosa Parks. Pamela is a lawyer and the widow of Julian Bond.

I’m excited to jump into this conversation about Julian Bond’s Time to Teach: A History of the Southern Civil Rights Movement. As a SNCC veteran, as a university professor, Julian Bond taught for two decades and this book is compiled from his teaching lectures. So everyone should check out this book as well. It’s a brilliant must-read to understand the Southern Civil Rights Movement. I want to jump right in with a question for Jeanne Theoharis: You were a student of Julian Bond’s. I’m very jealous, I wish that I had a formal education that was much stronger around the Civil Rights Movement. You write in the introduction to Time for Teach you say, “Julian Bond was a lifelong freedom fighter and a titan of social justice leadership. But alongside that persevering voice for justice, one of his great gifts was that of a teacher and a movement intellectual.” So, I was hoping you could talk to us more about how this book was made. What made him such a great teacher and what are some of the key lessons about how social movements specifically are made that he lived through, that he helped organize, and then that he taught a younger generation?

Jeanne Theoharis: It’s so great to be here. It’s so fun to be sharing the book with this community. As Jesse was saying, we began this series in March to kind of be a place for learning and other kinds of resources in this moment of online teaching and learning. And so it’s great to bring this book that we just published.

So Julian Bond, I had the great honor of getting to take a class, as Jesse was saying, with Julian Bond when I was in college, and then to serve as his teaching assistant. Then, kind of fast forwarding, one of the things I did not realize at the time was that he was really Julian Bond, as many of you know from Eyes on the Prize, has this incredible kind of voice and command of language. So I didn’t ever, I mean, again, I took the class, I TA’ed for him, and I never realized he was reading until when I was doing research for the Rosa Parks book, I happened upon a lecture of his. I was looking for a piece of information about the Montgomery Bus Boycott, I started listening to this lecture, and I was like, wait a minute, he’s reading.

Then one of the things I was so sad about when Julian died was that so many of us had gotten to learn from him, and really the ways that he taught the Civil Rights Movement changed the way I see it and the way I teach it, in part, because he really focused on the how of it. How was it made? How did it happen? And also, how did racism happen, and how was racism maintained? It was like, really, those were the kind of essential questions.

But I had been very sad when Julian died five years ago that, in some sense, the learning was going to stop from him. And then I sort of had this in the back of my head like, wait, I think he wrote these lectures out. I emailed Pam a few months after and I was like, “Did he write these lectures out?” And she said that he did not only read them out in full sentences, but he polished them over the years as he learned more and read more.

Because one of the things that’s really, to me, really magical about the book is it’s not an autobiography of Julian Bond. It is certainly leavened with exhibits of their stories, because he lived them, because he was the communication director of SNCC. But it’s also a book that is reflective of decades of scholarship on the Civil Rights Movement, because Julian was also a huge reader and scholar. And so it’s a really rare thing, right? It’s a rare thing to have a professor write their lecture notes out. Most of us couldn’t do this. It’s a really rare thing to have a combination between being someone who’s taking part in — and who is the kind of key activist on the frontline of this — and then spends decades studying it and enriching, and in some ways expanding, how he saw the events.

So, it’s a pretty unusual book, and I hope it will help us. Because in some sense, to give you a sense, the book really focuses on what we might call the modern or, as Peniel Joseph calls it, the heroic “Civil Rights Movement,” kind of 1954 to 1965 or so of the Southern movement. And yet it takes us really behind the scenes. It gets us past what Julian would talk about as the master narrative that we’d been given, the Civil Rights Movement. He used to joke around that it’s gotten reduced to “Rosa Parks sat down, Martin Luther King stood up, and then the good white people came and saved the day.” Obviously he was joking, but in some sense, that is what has taken hold, as increasingly, the Civil Rights Movement stands at the center of how the United States talks about itself.

Also, the version of the Civil Rights Movement that often is presented is such a stripped down, distorted version of what it was. So I think the book really allows us to see the work of it, the difficulty of it, the power of it, the organizing of it, the incredible cast of people that made it possible. It really takes us beyond a set of charismatic leaders, it expands the timeline. It starts decades before the action, just to show how people come together. It also, and this will be the last thing I say, it really foregrounds the role that young people play, because in many ways, SNCC was an organization of young people. One of the really exciting things about being a student was getting to learn from someone who knew firsthand the ways that young people can change this country.

Because the other lesson that very much comes through in the book is that you’re not necessarily going to be appreciated at the time. Recognize at the time that lots of people will disagree with you. Even people who will claim sympathy to you, right? So, your parents, your college professors, people in your city or town. I think learning from him that lesson about both the power of youth organizing and then also to understand what to expect was really crucial to me.

Hagopian: I love that. I love what you said about how he deconstructed the master narrative that says “Rosa sat down, Martin stood up, white people saved the day,” but also how he reframed the Civil Rights Movement not to just be about the the great leaders that were part of it — which there certainly were many, and he worked with many of them. I could see there could be a certain allure to tell the story only through those voices that he resists in this book. It’s so exciting to see what everyday people can accomplish when they link arms. I think that’s a crucial lesson for our classrooms. Thank you, Jeanne.

I wanted to ask Pam about something she wrote in the foreword to the book. You describe Julian Bond as in the vanguard of nearly every social movement of his time, and you talk about the many intersectional struggles that he joined — that it wasn’t just the Black Civil Rights Movement, but it was so many different intersectional struggles. I was hoping you could talk more about how he viewed and lived the struggle for social justice.

Pamela Horowitz: Sure. I think I wrote that. Having quoted Frederick Douglass about striking the first blow, and that Julian struck the first blow regarding most social justice issues of his time, starting with the Civil Rights Movement, of course, but then the antiwar movement. And some of you, if you were paying close attention, might have noticed that he became a character in the impeachment saga as it played out on television. Because the defense tried to use Julian Bond as a witness by quoting Bond vs. Floyd, which is the Supreme Court case that allowed him to take his seat in the Georgia legislature. And that was all based on an antiwar statement that SNCC issued while Julian had been elected but was waiting to be seated in the legislature. Julian didn’t write the statement, but he supported it. And in spitting, as given that SNCC was in the vanguard, that they were really among the first organizations to denounce the war — more than a year before Martin Luther King gave his famous speech at Riverside Church.

So, there was the antiwar movement, the women’s movement. Julian was very proud of the fact that it took many of its cues from the Civil Rights Movement. He certainly felt the same way about the Gay Rights Movement, and became one of the first national Black leaders to support gay rights as human rights to which we are all entitled. Even now, in such a short period of time, it’s hard to remember how much opposition there was. A lot of it came from the Black community. Julian, by that time, was the chair of the NAACP board of directors, and he’s certainly the one responsible for the board having passed a resolution almost unanimously — I think there were two votes out of 64 against it — supporting marriage equality. Afterwards, there was research that indicated that that was more important to the Black community than Barack Obama’s endorsement of marriage equality. So, that was a subject and a period in Julian’s life of which he was very proud.

Then there was environmental justice. His last arrest was at the Obama White House, over the Keystone Pipeline. Now, President Biden as one of his first acts, one of the first executive orders he signed, has ended the Keystone pipeline. So Julian would be happy about that, and we can claim another victory for his social justice activities.

Hagopian: Right on. Thank you for sharing that wide array of activism that Julian participated in. It meant so much when he came out for same sex marriage. I also remember Coretta Scott King coming out and standing for LGBTQ people. Those courageous voices, I think, were critical to building an intersectional social justice movement in this country. What an important lesson for educators in terms of how we act and also what we teach about. Excellent.

So, I want to turn to Judy, and ask you this — and other people can chime in as well. I was struck by something Jeanne wrote when she said, “The changes the Civil Rights Movement accomplished were not the province of presidents, of charismatic speakers, but accomplished by the efforts of freedom visions and sacrifices of everyday local people possessing great courage and vision. And many of those people were young people.”

And then Pam wrote, “Not unlike Black Lives Matter today — which Julian greatly admired — SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was bold and disruptive, challenging not just racial structures, but the various structures of society.” So, I was hoping that, Judy, you could talk about SNCC and the overall role that young people played in the Civil Rights Movement, and specifically why it’s important for teachers to know this history, and Bond’s commitment to music in the moment.

Judy Richardson: Oh, absolutely. First of all, I’m just so glad to see you all. You all were going through and saying you were from here and there, all coasts and south and north. I mean, this is a wonderful gathering. I’m just really honored to be here with you guys.

First of all, I should just say I met Julian when I was 19 years old. It was 1963. I come into the SNCC office. I’d been at Swarthmore College, I was taking off a semester, and I walk into this meeting. You will enter this national office thinking it’s going to be this wonderful, carpeted floor. And it’s not that. But it is also this hub of absolute amazing activity. It’s the research department, the print department, and it’s the national network of Friends of SNCC and student and campus friends. And it’s Ruby Doris Smith Robinson, who had just spent a month at Parchman prison. I mean, it’s all of these people. But then there’s also Julian. And, by the way, I should mention that all the people I see when I come into that national office in 1963, they’re all my age. I mean, I’m 19 years old at that point. They’re 20; I think Julian maybe was 21. Jim Forman, our executive secretary, was the older guy because he was in his 30s.

It was just amazing passion and brilliance and commitment to this movement. And we’re making $10 a week, which ends up being $9.64 after taxes. Now, what’s wonderful about Julian is that Julian was absolutely suited to being communications director. He had been one of the leaders of the Atlanta Student Movement. He comes into that first rowdy conference at Shaw University called by Miss Ella Baker. And of course, you cannot know about SNCC unless you understand more about Miss Ella Baker, who was our organizational and political mentor. She is the one who gives us that grassroots organizing foundation. She is the one who gives us her network.

So when Bob Moses goes into Mississippi, he knows to contact Amzie Moore because Miss Baker, former director of branches with the NAACP — [who is] constantly fighting against the hierarchy of the national NAACP — Miss Baker says to Bob, “If you want to do voter registration, you need to check with Amzie Moore,” whom she knows because he is part of her network. So, Julian is part of all of this. He had been a reporter for an Atlanta Black paper called The Atlanta Enquirer. Now, the Enquirer started because the other Black paper, the Atlanta Dealing World, was really conservative. As were, by the way, a lot of the presidents of those Black universities in Atlanta. So, again, it’s one of those misconceptions that all the Black churches and all the Black colleges were gung ho for the movement. Nope.

So, one of the things that Julian does is he works with folks to do this alternate Black newspaper, and then Jim Forman — who is the amazing administrator who pulls all of these pieces together — he brings in Julian. When I first came into this hub of activity, which again, are people who are my age, many of them look like me, and they’re changing the world. And so I come in, and I see Julian, he’s sitting in the communications department. Now, Dottie Zellner, who’s a good friend of mine, had been his assistant, then it was Mary King. He’s typing with two fingers, he has a cigarette hanging out of his mouth, because Julian could type faster with two fingers than I can with all of them, and I typed 90 words a minute.

So he’s doing this stuff, now he’s jamming out news releases, he’s making sure that the press knows, people from the New York Times are calling him. One of the things Dottie Zelner always said to me, she said, “One of the things about SNCC was that if we had a communications department, print department, whatever, if we said that there were five people at a mass meeting, there were five people. We did not exaggerate.” A lot of that has to do with Julian. Julian really was grounded in “you’ve got to be true, you’ve got to tell the real story (which will end), and you have to tell it truthfully.” He was also really amazingly erudite. I mean, Julian was the son of the former president at Lincoln University, the HBCU in Pennsylvania. He saw Kwame Nkrumah, all of these people, he saw Du Bois, he saw all of these people coming through this college. So, he brings that into this group of young people. Again, my age is 19 years old.

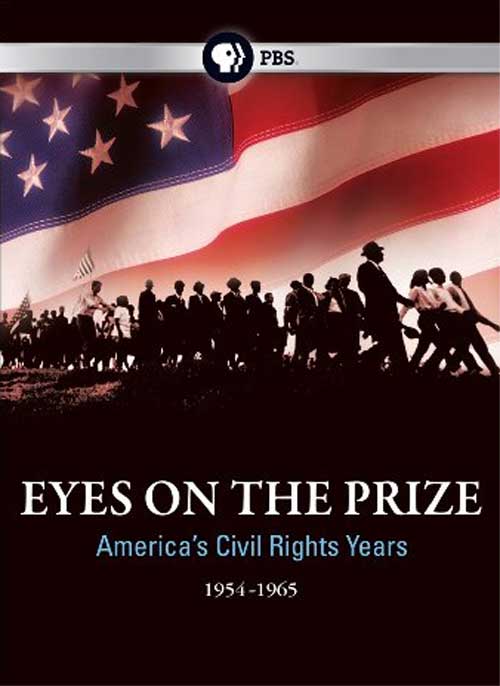

I would just say two other things. One of the things that, when she mentioned the narrator of Eyes on the Prize, of course, I worked on all 14 hours of Eyes on the Prize, and the early version. In the early version, Julian was even then going to be the narrator. And I won’t go into how amazing he was as a reader of all that, but I will say that it was perfect that he was the narrator, because that’s what the series did, when nobody knew any of these local leaders. You know, they didn’t know Jo Ann Robinson of the Women’s Political Council; they didn’t know Amzie Moore; they knew none of these local leaders. Eyes on the Prize: Storytellers, the Civil Rights Movement From the Ground Up, which is what we — including Julian — understood was the basis that was the foundation of the Civil Rights Movement, local movement leaders, local movement, people who were not just the troops, they were the leaders.

Then, second thing, and I’ll stop. When I was talking about gay rights, when I was a visiting professor at Brown University, I went to one, I think it was the first year that I taught there. A young guy comes up to me, one of the students after class, sso class has stopped, he’s now coming to me, and he says, “I am so glad that you mentioned Julian Bond’s name.” And I can’t remember, I could have mentioned him in so many different contexts, I don’t even remember. But he says, “I’m so glad you mentioned him,” he said, “because, as a gay person, and as a young white guy, I was so amazed to hear when Julian Bond came out in favor of gay rights and gender equality in terms of marriage.” He said, “Because as a spokesperson for the the ‘60s Civil Rights Movement, he had been hearing so many retrograde Black folks who are saying, ‘You can’t do this and you can’t do that.’ And on the NAACP board.” But what this young white guy, my student, was saying was, “I took such hope from the fact that this guy, who had been so integral to the Civil Rights Movement, was validating me from that end.” Now, getting the validation, he knew who he was, but the main thing was that it was a movement person — and a Black movement person — who was doing this. And that was really important to him.

Hagopian: That’s beautiful. Thank you for sharing all that history and helping us more fully understand the power of Julian Bond’s voice. That was beautiful. Does anyone else want to comment briefly on the role of young people in the struggle in the Southern Civil Rights campaigns, before I move on to a last question?

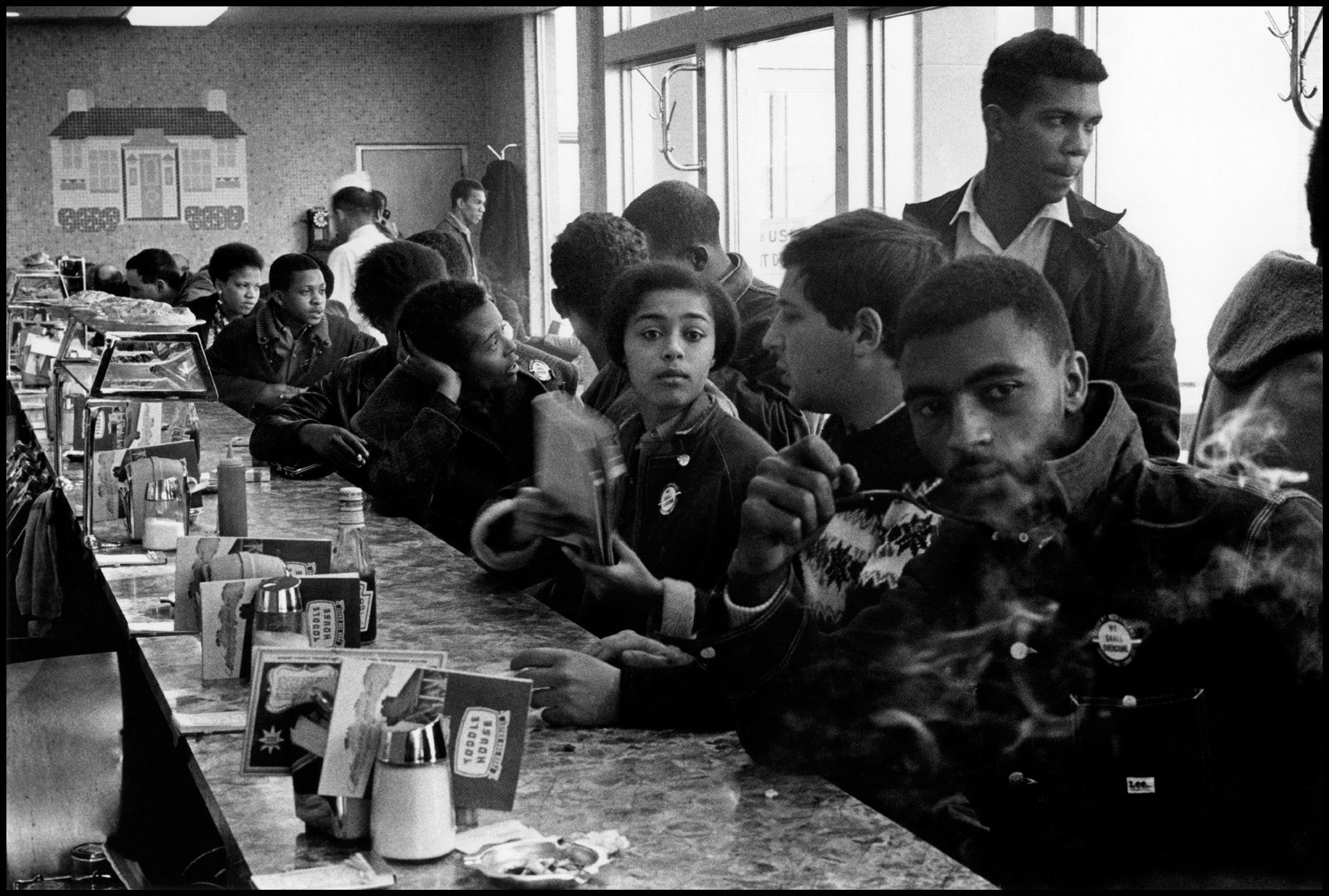

Theoharis: I think one of the things learning from Julian showed me was, well, a couple of things. So, one of the lectures I remember very much, and there’s the chapter in the book, it’s about the beginning of the sit-ins and how they began. So he tells us about Nashville and how they’re preparing. But then Greensboro just jumps the line, they just get going. And so these four young men in Greensboro, February 1, 1960, decide that they’ve had enough with talking about what’s wrong and decide to go down to the Woolworth’s and buy something to bring home, that they are willing to take their money and then refuse to. And I think one of the indelible lessons there was that it was just four friends, right? It was four people, and there were these moments where the way that he taught and brought the story down, and then by the next day there’s 17, and by the third day there’s 63. By the second day the women of Bennett College are there, and by the third day there are white people, white students, there and by the fourth day they’re overflowing Woolworth’s. So, you could both see how a movement emerges, but you also could see that you can begin with just this, because I think in some ways the master narrative puts it on such a pedestal that you can’t even imagine how you would do it. And then you see these four college freshmen, and you watch it sort of build, and so there was, I think, a cliche dumb way that people always talk about young people as the future and blah, blah, blah. And I think young people don’t believe that a lot of the times when people say that because it seems so saccharin. I think one of the things that’s so useful about Julian’s teaching, and hopefully the book, is that you get that but in a much more palpable, truth-telling sort of way, like Judy’s saying.

Hagopian: Yes, I love that. I mean, the lunch counters, the details of how young people organized that. I think one of the moments that I’m most inspired by with SNCC is when CORE started the Freedom Rides, and they got busted up. It was Diane Nash, if I believe right, from SNCC, who said, “No, we have to keep the Freedom Rides going or else the lesson will be that you just have to bring violence to our movement and we close up shop and go home.” Thinking about the teenagers in this country — the ones who finally led the struggle to break the back of Jim Crow — does take it beyond just the cliche of “youth are the future” and makes it concrete to see that the kids in our class have that same power.

And they’re beginning to see that power in the Black Freedom Struggle, again, that we saw erupt this summer when they chased police out of schools in city after city, and many other struggles. So I hope educators will look at the role of young folks.

I want to end with a question that everybody can jump in and answer. It’s really about how civil rights are often mistaught. Because if you’re teaching out of the textbook, or just out of the common understanding of the Civil Rights Movement, you’re going to fall into some traps. So I want to make sure the teachers who attend this call don’t fall into those traps. There are several particularly pernicious master narratives that I think Jeanne and Julian identify a lot throughout the book. But there’s the master narrative that the Civil Rights Movement was inevitable, that it was a popular movement, that it was a linear progression, that the Black Power Movement undermined the progress of the Civil Rights Movement, and many more. So I’m wondering if you could talk about these common misconceptions and what Julian taught you all to help you see the truth or what you experienced. Judy was actually in the struggle . . .

Richardson: Yeah, I would say, because I actually didn’t answer one of your questions, which was, why is it important to teach this? Because one of the things — and it’s what happened before we started Eyes on the Prize in 1979, actually — but if you think that only Dr. King was amazing (I mean, he was, there’s no question), but if you think he’s the only one, then you don’t know that you have to do it for yourself, then you don’t know that it’s your cousins and your uncles and your clergy and your sons, your mother, the neighbor down the street, they were the ones who did it and sustained it. If you don’t know that we were the ones who made the movement, then you don’t know you can do it again. Which is what they want you to believe. They want you to believe that it was only Dr. King, he was the only leader. It wasn’t Mama Dolly [Raines] in Southwest Georgia is one, Carolyn Daniels is one, all the people we knew who were the ones who were grounding us when we went into those communities, they would prefer that you not know about those people. Because if you don’t know they’re your neighbors, then you think, “Oh, well, if I get five people to do this and ten people, and then the ten become twenty.”

That’s one of the things. The other thing I would say is, if everybody who says they were in the movement was in the movement, we’d all be free now. The point is, I could go into a community, anybody [could], and for the first six months, it could be you, your local organizer, whom you’re working with, unless you are the local organizer, and her mother. And it would be that way in the mass meeting for six months, and unless people understand how slow this is, and the fact that you might never see the change, but if you do nothing, nothing changes. If you don’t get that, then you think you’re doing something wrong. I would often have young folks say, “Well, look, how did you all do this? Because it’s just me and my dorm mate or my roommate.” They’re not doing anything wrong. Stuff didn’t happen overnight. It’s like the Greensboro Four. Yeah, they did it. Before that, you had the Bennett Bells. So they had been talking about this stuff even before the Greensboro guys sat down on February 1, 1960. But there have been incidents, as Teaching for Change says, way before that, too. But the point is, it’s the cumulative effect. There’s something that just starts coming out when you start doing these movements, and you may not see it when you do it — and you may not see it for years — but that’s what I learned in the movement.

Hagopian: Thank you. We just have maybe a minute. but if you guys want to do a quick roundup of some of the master narratives we hope teachers shouldn’t fall into . . .

Theoharis: That is true; it is my favorite topic. It’s really one of the places where you can see how I am a Julian student. I think one of the things that also is in the book is a real attention to the substance of white supremacy on how racial politics is maintained. And the villains are much broader also than I think we’re taught to see, because part of the master narrative is Bull Connor, it’s Sheriff Clark, it’s the clan. And Julian was very clear that certainly those were some of the people who helped maintain the system, but also many of the people who would never have engaged in violence, but who also sat on the sidelines as other people did — sat on the sidelines as people organized against school desegregation, sat on the sidelines and allowed this unequal status quo to be maintained. So I think that’s one of the other real lessons that takes us past the master narratives.

As some of the people here know, I talked about this as the Redneck-ification of racism. Getting us to this idea that people can be polite and still be maintaining, and I think that’s really a theme we see in the book and Julian’s attention to the politics of it, the backroom dealings of it, the substance of it, how it sounds, how it works. That’s, again, much, much more complicated. Then the good guys and bad guys narrative that we’re given, where it’s like, and then the good guys triumph and we live happily ever after. And then we’re so surprised, “Oh, I’ve never seen the likes of this.” And you’re like, “No, we have seen the likes of this.”

Horowitz: Yeah, I think we should make it clear that every word is Julian’s that is in the book, other than our intros and the afterword. Because, as we noted at the beginning, he wrote it all out and he revised it. There was some light editing that we had to do, but it really is the next best thing to being in his class, because it is like being in the class when you read the book.

Hagopian: I wanted to begin with talking about Georgia, because given the history of voter suppression in Georgia and the recent electoral defeats of Republicans in Georgia, we wanted to talk to young people about the history of organizing that led to the moment that we’re in. I know Judy has a long history in Georgia, and others might want to comment on this too.

Richardson: First of all, let me just say that the book is really amazing. It’s just wonderful. The section on southwest Georgia really gives you an insider sense, in such a clear and narrative way, about what’s going on and what the forces are against them in southwest Georgia, the local leadership. But what comes through is also Charles Sherrod, who was SNCC’s person in southwest Georgia. He has for years now been married to somebody who was a younger person in Albany back then, Shirley. Shirley arrived and many of you know Surely because she was the person who was at the Agriculture Department during the Obama administration, who got hung out to dry. Well, she and Sherrod were SNCC staff person and field secretary. The two of them had something called New Communities and they’d consistently been working around voter registration, but also around Black land laws, all of those Black farmers who were so important to the movement. There was a humongous article, and when I say humongous, I mean a full page article in the New York Times. It talks about a Black farmer who is being trained by new SNCC person, Charles Sherrod, in Albany, Georgia, southwest Georgia, around how to try and get the loans. But it says in here, “even as the Civil Rights era started to bring Black Americans equal rights under the law, the rural exodus accelerated as White Citizens Councils throughout the south, weary of a surge in Black voters, very much tied to the Black land laws, explicitly targeted Black farmers for expulsion.” And we know, those of us who worked in the movement, that was the bulwark. They could get you out of jail when you were doing a voting rights demonstration. It was Black folks with land who were really essential to that. And I would also mention that in terms of what is out there now, that it is the Black land, folks. So let me just end with that.

Theoharis: Going back to our conversation about the master narrative, I think we saw a bit of that master narrative creep back up in the obviously incredible historic victories of Reverend Warnock and Jon Ossoff and being really attributed to Stacey Abrams and the legacy of John Lewis. And certainly, Stacey, the sort of tenacity and vision and persistence played a role. And certainly John Lewis’s longtime service in Georgia played a role. But we don’t get these victories because of John Lewis and Stacey Abrams; we get them because of a whole host of people.

Really, for me, there’s no way to not begin the story with Julian Bond’s election to the Georgia State House and the idea of harnessing the Black vote, that SNCC has that idea, that Julian’s campaign has that idea, and basically gets him elected in 1965 in Georgia. So, I think one of the things we need to do better as we tell the story of getting to the election of Ossoff and Warnock is all of the streams and strands that build this — really from SNCC to the present — and Stacey Abrams and her organizing and her vision is part of that. But she’s not the alpha and the omega of it. And I think we see that danger, and we just want one person and that’s how we’ve learned to tell the story. So I think what Julian would caution us against is that that’s like replicating even though it’s different, because now we have a woman — Stacey Abrams, not Dr. King — but it still partakes of that same sort of dangerous way of thinking about how change happens.

Horowitz: I think it was interesting in the piece in the New York Times yesterday with Stacey Abrams and her cohort, in the ten year project that they talked about in that article, and one of the things she said, Judy, really resonated with what you have said about Julian going into his would-be constituents and saying, “What do you want? And what do you want me to do?” And they said that was one of the things that they tried to do, and they recommend that other people [do too]. I obviously agree with that, but I think we can’t lose sight of the fact that you guys were doing that then after after. I think SNCC debated everything, whether or not Julian had won at all, and whether that was selling out or that was a chance to really change things from within. But then the story that you tell about him meeting with the railroad savings club . . . .

Richardson: So it’s 1965. We’ve just been through all this other stuff. Ivanhoe Donaldson and Charlie Cobb, particularly Ivanhoe, who later is campaign manager for Marion Berry in DC. Ivanhoe says we should start looking at electoral politics and how to bring this bottom up grassroots organizing into electoral politics. So Ivanhoe particularly, and Charlie Cobb, are the campaign managers and I am the office manager. I’m also the only office staff. We’re on Hunter Street, next to Frazier’s restaurant on the main drag in Atlanta. Julian was supposed to be talking to this group called the Red Rosebud Savings Club. It was this elderly Black woman who just wanted him to come talk to them about what his campaign was going to be. So I’m waiting, because we’re supposed to be out Gordon Road, and I’m waiting for him to come so that we can drive to the meeting. And he’s not there.

I start getting worried because I don’t know how to talk to more than two people, even if I know them. But he’s not there, you know? So I get in the car and I start to head out toward Gordon Road, and then I see him. And I said, “Julian, you got to be in the car.” So he gets out of the car he’s in, he gets into the car I’m driving, [and] we head out to the Red Rosebud Savings Club. It couldn’t be more than I would say ten or eleven older Black women; he walks in, and you would think he was the prince. You could see their eyes lighting up. “Oh, I need to get him to meet my granddaughter.” You know, all of that.

But the main thing for the purposes of this session is they asked him, “So what are you going to do?” And he says, “What do you want me to do?” What he’s doing is what we assumed in SNCC would happen with electoral politics, that you would bring that grassroots organizing — non-hierarchical, all that stuff — into electoral politics and let the people speak. That was another thing, right? So his thing is, well, tell me what you need? What do you think should happen in your neighborhood? Then he starts writing it down. And you could see these women, they really are amazed that he’s listening to them. And when he left, they really did believe that he was going to try and do some of this stuff, if they elected him. And he was, you know, he wanted his job. And on this stuff, he was bringing the SNCC thing into electoral politics, and they loved him. They loved him.

Hagopian: Right on. Thank you for telling that story. We have a couple more minutes here, and I know one question that I had asked earlier that we didn’t get to is about the role of music in the movement. I’d love to hear what you all think about that, what Julian thought about that.

Horowitz: Well, Julian thought it was very, very important to the movement. In fact, he had a lecture on music, which is not included in the book. It was really a matter of playing the songs and then letting his students sing the songs. And it almost always happened that he taught fairly big lecture classes, and that there were at least a handful of people who really could sing. Even in the context of his classroom, it was kind of a bonding, if you will, experience when they all started singing.

Today I just reread the chapter, All Benefit and Eat. That’s where singing started because that’s where the original Freedom Singers were from — Cordell Reagon, Bernice [Johnson], Rutha [Mae Harris]. That introduced music and it almost took the roof off the church. [Charles] Sherrod writes, and I think, “I don’t think the mass meetings were never the same after that, because they always sang.” It was a sense of community that you didn’t get any other way, and it helped the people not be afraid. Because how could you not be afraid? But it reduced the fear.

Hagopian: Yes. Anyone else?

Theoharis: One thing that we are working to do — because people have been so interested in Julian’s lecture on music — one of the biggest debts of gratitude that Pam and I have is to our research assistant, Eric Wallenberg. Eric went to UVA and pulled the lecture first and really helped. He did a lot of the work around the citations. He has pulled together some of Julian’s lecture on music with links to either YouTube or SoundCloud. And Beacon Press has a blog called the Beacon Broadside. So probably within the next week or two, they’re going to put that blog piece up so that people can both see some of Julian’s commentary with the songs embedded so that you could also listen to them or play them in class. So, stay tuned for that.

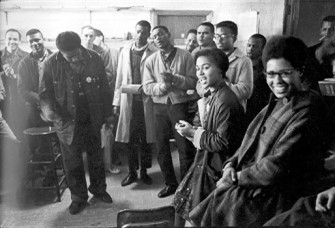

Richardson: I see Deborah has a photo of us in the work room. Now you’ll see on the one with the mouth open to the far right, upper right hand corner, Julian cigarettes sitting out of his mouth. [James] Forman is there. You will see Marion Berry is there, in the center with the raincoat on. I’m the one also in a coat, a denim coat, which we all wear. Then behind me, near Julian, is John Lewis. We’re singing because it wasn’t just that it was to stop, as Dr. Bernice Johnson Reagon, who comes out of that Southwest Georgia Movement says, there were times when you would sin, you would name the people who were opposing you, and that by doing that, it was almost like you were putting up a wall of sound that they had to get through, this wall of sound. Sheriff Pritchett, bad Terrell County guys, all of those, they had to come through that to get to you.

But even within the staff, when you were collating, because we didn’t have all the highest equipment and stuff, you had to collate all the mailings that were going out, you had to stick them in the envelopes, you had to put the stamps on, all of that stuff. You sang while you did that. Sometimes it ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around. People have the sense of music as just Kumbaya, We Shall Overcome, [but] no, it was defiant. You would sing it when you were getting arrested. There was a sense of force, there was a forcefulness about it that was really important. And it made you feel like nobody could touch you. That’s beautiful.

Hagopian: Yes, thank you for sharing that. My dad talks about how it was actually the music that first opened the world of activism to him — whether it was movement songs or it was R&B singers bringing in themes about social activism — that introduced him to the movement. So, I think it’s such an important thing for educators to teach about. And we have the book Rhythm and Resistance, somebody threw in the chat, to introduce kids to the freedom songs from the struggle, then also have them find songs today that are helping to inspire activism and social change.

Richardson: We used the popular songs when we did it. You know, “Dog, dog, dog, dog, my dog, love your dog.” That comes from, I think it’s Ray Charles, we got a few things from Ray Charles, you know, because we’re 19, 20 years old. So we’re bringing all that other stuff in, just the way they’re doing with hip-hop and rap now.

Hagopian: No doubt. Thank you for that. Wow, we are coming right up on time. I would love to just keep asking you all so many questions about the movement. We have to do this again because there’s a lot of things I still want to learn about. I hope this was a great jumping off point for everybody and that you will read the book itself, Julian Bond’s Time to Teach. Order it and check it out and use it as a guide in your own classroom for teaching about the Southern Civil Rights Movement. And I hope that everybody really enjoyed this special opportunity today.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the resources recommended by the presenters and also by participants in the chatbox.

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today?

Thinking about the master narrative and what can help more students at a younger age have a more clear idea of how to be an activist — and the many facets of activism.

I learned that the Civil Rights Movement was not just popular historical figures like MLK, it was made up by students like me. I am still in college and I think for the first time I realized that the Civil Rights Movement was so much more complicated than I thought.

Textbooks don’t teach that the leaders were ordinary people, and the villains are much broader than the KKK and white citizens council.

I’m just starting to learn about Julian Bond, so this was a great introduction to me for who he is and what he did!

That big change happens through many pieces, actions, components building on one another.

I learned about Julian Bond. I had not previously heard about his amazing life and the fact that he had written records of all his lectures so the world could read them is simply amazing to me.

Movements for social justice are made of so many people and that we need to counter the narrative that it was a select few who made it happen and that it was in some way linear or inevitable. There is a long line of stories and people who have worked to make progress. We need to work to help our students see their part in movements and to find agency in our curriculum.

It is important to record our movements to teach the next generation. The class spoke to the cultural power of passing down our stories.

Something that I know I will continue processing and ruminating after today’s lesson is the idea of being a good mentor to youth activists. As a “teacher,” I try not to take on the role of “expert” and instead try to focus the classroom around collectively building knowledge. I think I can improve on this approach by thinking more deeply about mentorship.

The time it takes, the value of working with only a few people, but getting started, the need for some backroom dealing at times. Mostly I loved the passionate and joyful energy of the panel, the love between you, the joy in the work no matter how long and difficult it’s been, thanks for sharing that. I sense the length of the struggle.

Judy’s take: If all the people who said they were in the movement were in the movement, then we would all be free.

The importance of grassroots work and patience in making change. Judy’s comment, “Even if your mass meeting is just a couple of people for months, keep at it,” paired with the reminder that if that groundwork is there, when people do act, like in the sit-ins, they can grow with the community that ready to step up.

I loved learning about Julian Bond bringing in his “erudite” ways to SNCC. This feels important for students to learn! Attending these sessions & hearing names over and over again of the ordinary people in the freedom struggle (Dottie Zellner, Bernice Reagan Johnson, Amzie Moore, Charlie Cobb, etc.) feels like I’m soaking in some of my own erudite to take into the classroom with me!

The fragility of history and the truth. I understand more now about why the truth is left out of so many parts of history, and why it is so important to tell more than one side of any story. It also important to tell the whole story, even the ugly parts.

It’s difficult to pick just one thing. If I had to, I would say it was learning how Julian Bond valued young people and actually taught the significance of everyone’s contributions, not just the big names.

Jeanne said something about how when we are distanced from seeing and understanding that it is people like ourselves in the movement we don’t believe we — ourselves — can be part of making the change.

What will you do with what you learned?

Read, think, and apply the ideas, texts, and questions I encountered today into my teaching and curriculum, especially as I plan for next year.

I ordered the book of Bond’s lectures to use in one course in the fall.

Share with the teachers I am working with (I work with new teachers). Bring this conversation into our anti-racist, anti-bias discussions.

Continue to highlight the everyday people that are the movements we study and the long history of fighting for change.

There’s always such limited time to focus on any given time period in a high school U.S. survey course, but this class really inspired me to make sure that what time we do have is largely focused on social history/using events as case studies, rather than focusing on individual already-famous leaders.

Continue to check and disrupt the master narrative in my teaching. Use the examples of teens from this period to inspire my students.

I will be less afraid of teaching this history the “wrong” way.

In the break-out group, our facilitator said, “would anyone remember what MLK said if no one was there? Where was the power?” I think this idea needs to guide discussion about the movement with more students to show that it was indeed a group effort as well as a non-monolithic effort.

I’ve focused a lot this year on making sure to not just talk about a hero or a leader and talk about how a movement is made up of people and I want to continue to reinforce this. I want to make sure to address that these people can be neighbors, family members, community members. Anyone can be an activist.

I will stress the cumulative nature of change and not be discouraged when folks say I’ve been working on this for the last 2 years of my 18-year-old life and nothing has changed and I am tired. I know the work must keep going.

I am excited to bring these ideas into the classroom! I have taught about Freedom Summer as an essential, grassroots CRM campaign with students using the SNCC digital gateway, and I am looking forward to bringing Bond’s perspective into that unit to shape it more deeply.

I’m refreshed after the joy in this session! So that’s one of the most helpful contributions to my instruction right now: energy! I love learning the moments from the freedom struggle + connecting with people on the sessions. I love knowing more about the people in the movement so that, as I get to know students in my classes, I can introduce them to people with whom they can relate.

I plan to embed what I learned both into my classroom and within the current local protest community in Seattle. I teach 8th US history which covers up to Reconstruction, so I do not explicitly teach the Civil Rights Movement, but I am continually working to thread together the past with the present and help students see the themes throughout history in regards to Black liberation.

I will be sharing all of this with my students, especially the insights that individuals can create a movement instead of waiting until it’s fully formed to join in.

I appreciate that after each session, I have a broader understanding of the depth of the civil rights movement. There is not one single story or entrance point, but rather so many.

What did you think of the format?

I liked hearing from experts, people who knew Julian Bond personally.

I love the framing of the pedagogy of the breakout rooms.

Everything was wonderful. Very engaging and informative. Judy, Pam, and Jeanne all blew me away with all their insights and stories.

I liked the ease of the conversation between the presenters, also the time to reflect and process with people in the breakout room.

Great format — breakouts always a highlight — but speakers are always fabulous! Tonight we were able to hear from some real foot soldiers of the movement — so inspiring.

It was very convenient to do this virtually. I enjoy the introduction with the speakers who had first-hand experience with Julian Bond. The breakout room was a bit short, we barely got through introductions and had time to speak to one of the questions.

I appreciated the suggestion that people be equitable in breakouts: everybody talks once before anybody talks twice. Appreciated interactions between Jeanne, Pam, and Judy as well as the emcee whose name I didn’t catch as I logged in a few minutes late.

Y’all did a great job! I liked the big group, small group, big group approach. Break-out rooms were a good length for me because we weren’t very talkative.

This class was very well organized and implemented. I think everything went smoothly. I loved all of the presenters. The breakout session went well. Perfect amount of time for discussion. Too much time can be intimidating, especially when you haven’t had a chance to prepare for discussion in advance. The breakout session was “low-pressure.”

It worked well overall from my perspective in light of the timing constraints. Thank you for all the work that goes into facilitating this kind of online event.

I believe all aspects of the presentation were very nice. The breakout room was fun, because it is awesome to see people from all over the country coming together and sharing ideas.

Everything was “just right,” because, at least I, was left both wanting more, and saying “I can’t wait to share with my students & my colleagues what I learned tonight.

There will never be enough time so I won’t comment on it. I think it would be cool to incorporate jamboards or something similar so we can start creating as educators while in a breakout room. I think the group size was perfect, we had 7 people in my room.

Super great, challenged myself to stay on in the breakout room and so glad I did. My only feedback is that not being super familiar with Julian Bond’s work made it hard to answer the first question. Our conversation was much more fluid when we got to the second, and we could have just had one q because of time.

The problem was that we were asked to talk about his life without having read the book or anything about him before attending, so we were stuck rephrasing random anecdotes from the speakers.

The format was ideal, although I would have definitely appreciated more time discussing with my breakout group.

Additional Comments

Thank you for making this open to everyone, not just educators <3

I was already familiar with Judy Richardson and her work with SNCC, but this was my first opportunity to hear her speak live and she blew me away!

Thanks so much for making this happen! It was an honor to listen to the speakers. I feel more connected to the movement.

It was really, really such a special opportunity to hear from Judy Richardson and Pamela Horowitz.

Thank you so much for putting on this series! You all inspire and help me to be a better facilitator in my students’ journeys and social justice work.

Thank you so much for having this event. It was a great honor to be in the space with these legends of the movement and to hear their stories firsthand.

Breakout 17 was well-facilitated. Thank you for the links. I have saved the photo. I wonder if Gloria House or Robert Moses were in it. The panelists and facilitator were excellent. An entire lifetime of activism! OMG. Yes, children need to know. YOU ARE the FUTURE!

I loved Judy’s quote: “If everyone who says they were in the movement were in the movement, we’d be free by now.”

Thank you for continuing to organize these events and broadening my understanding of history so that I can bring it to my scholars in the classroom.

Thank you! It’s always great to see people & connect over meaningful topics. Especially true for me at this time because I need to be with “colleagues” like the educators in these sessions who are really working in ways that make a difference. The day-to-day routines & interactions at my current school can tear me down and make me feel really weak, but woo-hoo — tonight I’m feeling a recharge!

I don’t remember my breakout room number. But Ursula was my facilitator. She was AMAZING. Ursula gave me a confidence booster, as I am not a teacher. She shared that based on what I’m doing, I don’t have to be in a “classroom,” because I am a teacher. For sure, teaching is my passion. I love working with the youth at my church. Helping learn the value of their voices and how they can affect change.

Thank you for another outstanding course, that offered something for everyone who attended, no matter their age, their profession or their background.

It was really, really such a special opportunity to hear from Judy Richardson and Pamela Horowitz.

Thank you for continuing to organize these events and broadening my understanding of history so that I can bring it to my scholars in the classroom.

Presenters

Judy Richardson was on the staff of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Georgia, Mississippi, and Lowndes County, Alabama (1963-66) and ran the office for Julian Bond’s successful first campaign for the Georgia House of Representatives. She founded the children’s section of Drum & Spear Bookstore and was children’s editor of its Press. Her SNCC involvement has always been a strong influence: in her documentary film work for broadcast and museums (including the award-winning 14-hour PBS series Eyes On the Prize, PBS’ Malcolm X: Make It Plain, and Scarred Justice: The Orangeburg Massacre 1968); and in the writing, lecturing and workshops she conducts on the history and relevance of the Civil Rights Movement. Read more.

Pamela Horowitz was one of the first lawyers hired at the Southern Poverty Law Center in 1974. She also worked as a legislative counsel with the National ACLU and then entered private practice, where she remained for the next 25 years. She currently serves on the boards of the NAACP Voter Fund and the SPLC. Over the course of her life, she worked in partnership with her late husband, Julian Bond, in multiple public, private, and academic projects and is involved in several activities honoring his legacy.

Jeanne Theoharis is a distinguished professor at Brooklyn College. She is the author or co-author of nine books and numerous articles on the Civil Rights and Black Power movements and the politics of race and education. Her books include the award-winning titles The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks: Young Readers Edition, and A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History.

Jesse Hagopian is a U.S. history teacher at Garfield High School and on the staff of the Zinn Education Project. Hagopian is a Rethinking Schools editor and is the editor and co-editor of a number of books including More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing, Teaching for Black Lives, and more. He plays a lead role at the Zinn Education Project in the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle campaign. Read more at Jesse’s website, I Am An Educator.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn