So many insights! “Reconstruction didn’t fail, violence overthrew it!”; “Freedom making and freedom taking”; “Trauma sensitive lens”; “Lay another track on the freedom struggle.” This class is laying another track on my understanding of this incredibly rich history.

I enjoyed the large think-tank, sharing information, and the Q&A portion. It was amazing to see how many educators are teaching similar concepts and the adversity that many are facing to teach a very challenging yet important topic.

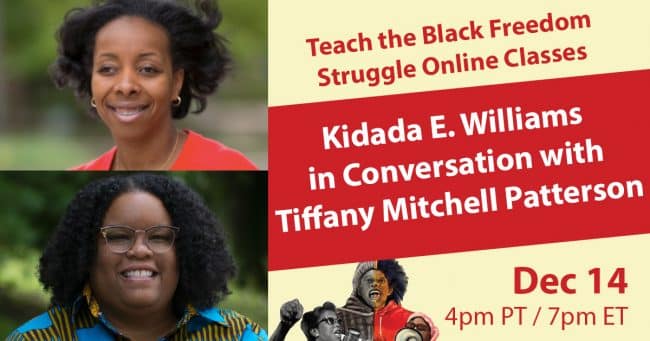

These are reflections from just two of the participants who joined the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle class on Reconstruction: Repression and Resistance featuring Dr. Kidada Williams in conversation with Dr. Tiffany Mitchell Patterson. On Monday, Dec. 14, 2020, they joined a community of people’s history educators — public historians, guardians, grandparents, and classroom teachers — to speak about African American survivors of racist violence in the context of Reconstruction, drawing parallels to the present.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

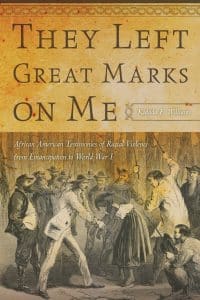

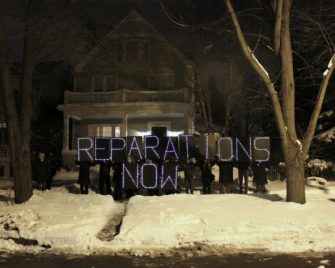

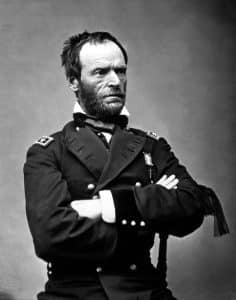

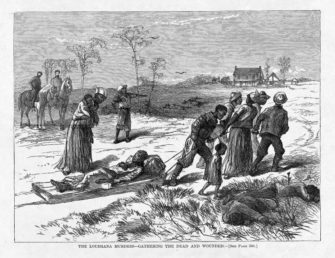

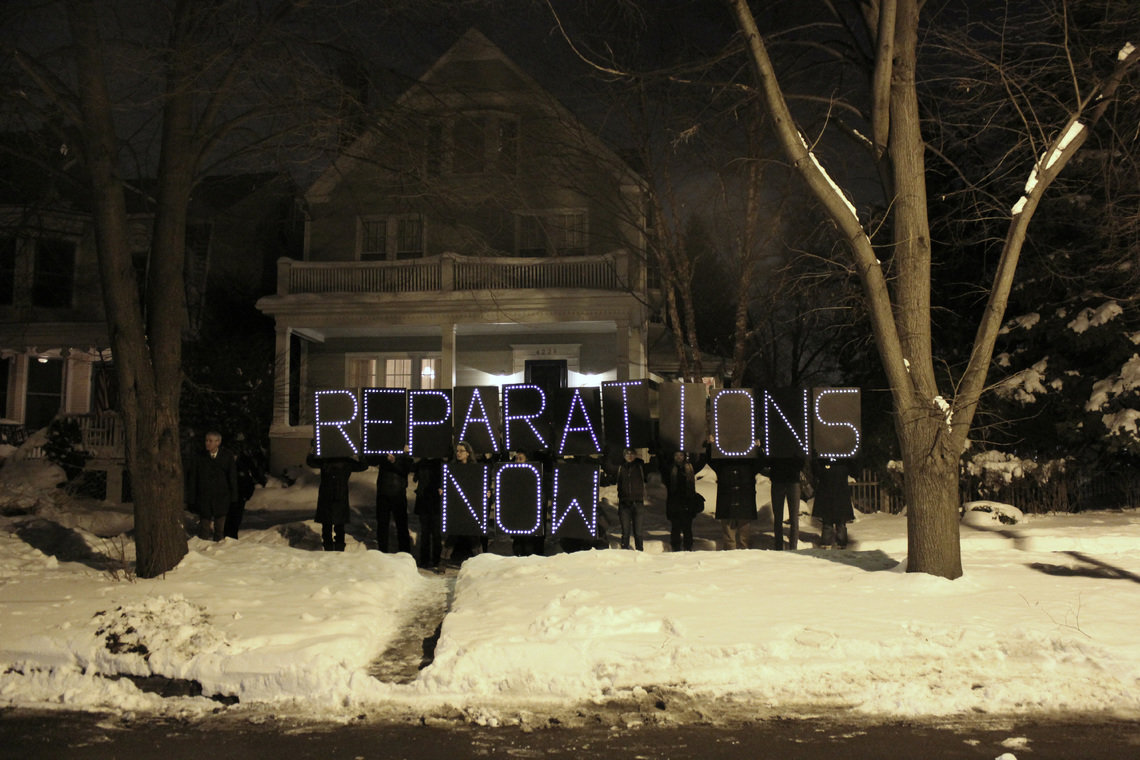

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion. Tiffany Mitchell Patterson: I am so happy to introduce Dr. Kidada Williams, a Detroit-based writer and historian who studies African American survivors of racist violence. Dr. Williams is an associate professor at Wayne State University, she is author of They Left Great Marks on Me, and co-editor of the Charleston Syllabus: Readings on Race, Racism, and Racial Violence. Her podcast Seizing Freedom will be released in early 2021, and we cannot wait. So, we are looking forward to that. Thank you, Dr. Williams, for joining us. Kidada E. Williams: Thank you so much for having me. I’m really looking forward to this discussion on Reconstruction. I think it’s one of the more challenging topics to cover, to teach in the classroom. But I think it’s one of the most important eras of U.S. history. I’m really looking forward to having conversations with you all about how to teach it, or and how to teach it well, more specifically. Mitchell Patterson: Yes, that’s exactly what we want to discuss. To start off, I know, oftentimes, as teachers, we use the cover as a preview. The title of your book, They Left Great Marks on Me, can you really explain the meanings — because I’m sure there’s more than one — for this book title and how it frames Reconstruction? Williams: Well, the title comes from the testimony of an African American woman named Mary Brown. Her family was attacked by a white terror gang during Reconstruction and she bore the brunt of the gang’s attack on her larger family. And in this she’s viciously beaten. When she testified before Congress, she says of her injuries, “They left great marks on me.” And what she’s doing is, in specifying this detail, she’s participating in a larger strategy of survivors — we see them deploying this effort to push back against white supremacist efforts to discredit them as victims of this violence. That story frames the larger story of what I see as freedom-making and freedom-taking people. That would be African Americans in the context of Reconstruction. They are people, like Mary Brown, who are working to make freedom real, and white violence is being used to undermine their freedom and to eventually overthrow Reconstruction. It speaks to the larger efforts of this community of survivors to communicate the ways racist violence completely transformed their lives. And I really wanted to tell that story because it plays a role in not only their own experiences of violence, but encouraging future generations to play an active role in trying to stop this violence and bring about larger civil rights reform. Mitchell Patterson: Do y’all have goosebumps? I have goosebumps. Freedom-making, freedom-taking. Okay, I’m going to try to contain myself as we go through. Catch these gems, y’all, and please hashtag them. Let’s talk about your use of testimony. You brought in a lot of complicated, nuanced testimonies as this act of resistance. So, can you share why you centered testimony in your work? Williams: Well, I centered testimony in the work because I think the testimonies are historically significant, for one. Black people, they talked about, they reported, they testified about what they saw as this war that white southerners were waging against their freedom. They report to local authorities; they report to members of Congress, the Freedmen’s Bureau; they write letters to elected officials, to newspapers and civil rights activists, etc. So their testimonies, I believe, counter the lies perpetrators and their enablers tell about Reconstruction, and about Black people — as you know, Black people and freedom, about Jim Crow, about lynching. I think that their stories also reveal what they believe this violence did and was still doing to them. I don’t think we can really understand Reconstruction violence unless we understand what the people who experienced it directly believe that it did to them. One of the things that we end up doing, I think what we see is, they’re going to be the ones who produce the records that help us really understand what happened during Reconstruction — that Reconstruction didn’t fail. It’s violently overthrown. We get that story when we pay very close attention to the people who were targeted by that violence. Mitchell Patterson: Let’s dive into one of those stories to help illuminate that further for us. There are many stories in your book and I’m thinking the story of William Coleman, for example, and how you just really communicate this duality of Reconstruction, and perhaps the longer story of the Black Freedom Struggle. The incredible success of efforts by Black people to get free and the ferocious commitment of white power to dismantle those successes. So, why are these stories important and how can they serve as these counter narratives to the master dominant narrative in U.S. history for students? Because this totally runs counter to the textbooks. Williams: I think it’s frustratingly popular to talk about Reconstruction as a failure. When people use that language, what they mean is that Black people failed, right? Black people failed at freedom, they failed to live up to the promise of emancipation. And that story is one that can only be told if you completely ignore the accounts of people like William Coleman. William Coleman, like the vast majority of people who are targeted with violence during Reconstruction, does everything right. He gets free, he’s working, he has a little bit of land, he has livestock, he’s voting, he’s doing everything he’s supposed to do. He’s even doing what white Radical Republicans advise African Americans to do once they get their freedom. And because he’s successful, he is targeted by the white planter who decides that instead of paying him his share of the crop at the end of the season, he’s going to deny it to him. Then when William protests, he sets the klan on him. And so what we see is that historians, when they tend to talk about cases like William Coleman’s, they focus on the fact that he’s disfranchised. Because that’s often the story historians and the larger public like to tell about Reconstruction, which is these battles between Congress and the president, and then eventually the Supreme Court. Those are important to the story, but they’re not the only part of the story. And when you focus only on that you miss the reality of what else is happening to people like William Coleman. So, William Coleman is disfranchised but losing the vote. In his view, it doesn’t appear to pale in comparison to losing his land, to losing their lot, his livelihood. Because his family has to flee for their safety, so they lose their land, they lose their livestock, they lose their livelihood, they lose their sense of community and place. They lose all of that. And what they make clear when you focus on there, when you look at the testimonies of people like William Coleman, you see the cascading, the compounding loss. We often think of Reconstruction violence as something that is a one-off — they were attacked, the attack ended, everyone else moved on. And what we see from survivors, when we pay attention to their testimonies, they never use the past tense. When they talk about violence, they always use the act of present tense, because the effects of the violence for them are ongoing. So, when they testify about this violence to Congress, what they’re trying to let them know is that we are in the process of not only losing our lives and our livelihoods, but also our freedoms. And they’re very clear about that as part of a loss. But again, we only get that when we pay attention to their testimonies, and when we don’t discredit them, when we acknowledge their authority, their ability to speak directly to their own personal experience of this violence. That’s part of this larger story of Reconstruction that often gets missed. But I’m biased. I also think that it’s probably one of the more interesting, but also heartbreaking parts of Reconstruction. Mitchell Patterson: Can you share another testimony with us? Because I think you’re really spot on in the way that this history is often presented, and racial violence and racism is very limited for our students. Like, they only hear these very singular narratives, or an attack happen, or lynchings. And that’s it. Can you share maybe a nuanced experience of racial violence that might tell a fuller story that we could use in our classrooms? Williams: I think one story that we could tell would be the story of Henry Adams. Henry Adams was someone who collects all of these testimonies, these accounts from African Americans who are targeted by Knight Riders and other vigilantes in their communities. He’s also part of what will become the “exoduster” movement. One of the things that I think we can see in African Americans’ testimonies and inactions, like Henry Adams, is a diversity of responses to this violence. People are targeted [and] they do participate in armed self-defense. They do report violence, they flee, they migrate, they leave communities. And stories like Henry Adams’s testimony before Congress when they’re investigating the exoduster movement, sort of throws light on all of this. But when you look at it, you have to sort of understand it within the context of all of these other testimonies that are largely telling very similar stories of, again, that freedom-making and freedom-taking people and the price that they’re going to pay for doing so well with emancipation. Again, the vast majority of people who are attacked have land or they’re about to get land. They’ve got jobs, they’re getting businesses, they’re acquiring lost livestock, they’re doing everything they’re supposed to do — and probably everything many of them had dreamed about doing while they were enslaved. And they are attacked for it by people who don’t really believe in American freedom, who don’t really believe in American democracy, and who want to hoard the privileges of American freedom for themselves. For some of them, they want to retaliate against African Americans and take every single thing that they’ve built. They want to make sure that they have nothing but their freedom. And I think the larger testimonies reveal that, but again, if you only focus on what’s happening at the White House and the halls of Congress, then you missed that part of this really important story of American freedom and democracy. And I think that’s the more interesting story. They’re connected to be sure — African Americans can’t make some of the moves that they’re making at the ground level without what’s happening at the top — but if you pay close attention to what’s happening with Reconstruction, African Americans themselves are driving what’s happening at the top. We won’t get the Civil Rights Act of 1866 without African Americans, Blacks, especially Blacks who were free before the war, pushing for and insisting on their right to have rights, and to have them spelled out in great detail. And to say that being paid for my labor isn’t the only thing [that] justice looks like after being enslaved. It requires all of these other things, many of these rights and privileges that other Americans have taken for granted. What African Americans say is that we need these rights recognized, and we need them spelled out. That’s how you get the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the 14th Amendment, the 15th Amendment, etc. You have to look at this freedom-making and freedom-taking people to understand what’s really happening in the context of Reconstruction. Mitchell Patterson: How can we as educators — because we talked about how this is such a fruitful area for us to explore, but also extremely difficult — how can we surface white supremacist violence in our classrooms in ways that don’t desensitize nor traumatize, and ultimately support these stories of resistance? Because so many times students say that they don’t hear about African Americans as agents, as resistors. So, how can we do that balance? Williams: Well, I think what you have to do is you have to focus on: I’m biased as an African American, I’m always looking at the Black people, where are the Black people? What are the Black people doing? Right? But it’s in that focus that you get to see the complexities of African American life, the beauty and joy of African American life, what they do with freedom, and the price they pay. I think that the way you do this is you follow a diversity of African Americans. And that exists in the record. You’ve got Blacks who are free before the war, Blacks who are in cities, women, then people in political power, etcetera. So if you tell the full story of Reconstruction, you’ll find the kinds of examples that your students benefit from seeing — African Americans as agents in this history, as advocates of their own freedom. So that’s certainly there in the record. We as educators just have to be ready and willing to look at them and look at a diversity of sources. But I think that’s what our students need — to understand that African Americans aren’t like these thought characters, that they are actual human beings, thinking, sentient. What they’re trying to do in this moment, and the kind of tug of war that they are experiencing with people who are committed to this white supremacist system. But I also think that as we do that, when we encounter violence we don’t necessarily need to shy away from it. I think that in teaching our students, we have to be aware of the possibility of harm, especially for students who may be descendants of people who were targeted. As we deal with this history, we have to make sure that we don’t hold ourselves to a lower standard of care for our students, especially when they’re engaging histories of violence against Black and Indigenous people. So, we can’t teach this history in an unthinking and careless way. And I use that because I often see that with a history of violence against African Americans and Native Americans. There’s more thought taught into how one teachers 911, than how one teachers Reconstruction violence or lynching. Because the 911 attacks are seen as a tragedy that requires care and thoughtfulness about how the information is presented to students, and that violence against African Americans doesn’t get that necessarily. So we have to be aware of that. I think as educators, we have to look for age appropriate materials and we have to be aware of that part of the ethics of care and responsibility for our students and teaching them the history. Unfortunately, with African Americans and racist violence, there’s no shortage of examples that would be useful to teaching the history from a variety of angles — for women, for young people, even children — who testify about violence. For example, in the WPA narratives, a lot of African Americans who, when they’re interviewed about the violence, they were kids at the time, and so they’ve got a unique perspective on Reconstruction violence, as people who were young at the time and had to live in the life created, or torn apart, by that violence. Make sure students process their own feelings about the injustice that they are witnessing in the historical record, give them time to deal with that, but then bring them back to reckoning with the reality for the historical actors. I think that’s important to do, and to balance that with African American examples of resistance. There are plenty in the records that are age appropriate, we just have to be willing to look for them. There are records too through the Zinn Education Project, and there are records that are now made available all over the place where you can get a sense of the variety of experiences of violence and resistance to it. But you’ve got to be aware of it, it’s got to require some thought, it’s not something you can just do without potentially harming your students or making it harder for them to understand this history. Mitchell Patterson: You mentioned the violence inflicted on different groups, and ways that it’s gendered, or children that experienced this violence. Were there any differences, and could you speak to a bit of how that works when violence is not only racialized, but gendered? Williams: Well, what I’ll say is that no one is spared — not women, not children. I think we often think of men being targeted because they ran for office, and because they were heads of households. But I think you only get that if you don’t pay attention to the testimonies. You miss parents talking about their children being harmed by this violence, but also their children acting as agents in this violence. Children want to help, they try to protect their parents from the men who are coming for them, they run away, they hide under the bed, right? They do all of this. That’s because no one is safe. There are also people who are disabled. Disabled people, they respond differently. They have to draw from a different deck when it comes to figuring out how to respond to this violence. There are people who freeze, right? We often think of this fight or flight response, [but] we don’t account for the people who freeze — they can’t make any decisions to do anything to protect themselves or anyone else while they’re in that state. I think when we think about the diversity of people who are targeted by this violence, we also have to keep in mind the diversity of responses. We shouldn’t lionize certain kinds of responses or prioritize other certain types of responses over others. We’ve got to look at the full, messy, complex human spectrum. Mitchell Patterson: I think that’s so powerful for students, to be able to see that range, because often they’re not given that complexity and that depth through the textbooks. What are some of the forms of resistance that you saw, and some of those varied responses? Williams: So, it runs the gamut. People run away. One eight-year-old girl, her name is Emily Jeter, she recognizes one of the men who’s hooded, and she calls him out by name right during the attack. She essentially says, “You let go of me, Mr. Hoesapple.” And he does, and promises that he won’t hurt her. He actually keeps that promise. But those records, you know . . . Emily Jeter doesn’t testify before Congress, [but] her father Columbus does. So, I think that when we’re looking at these kinds of records, particularly testimonies, we have to look at them in greater detail than we’re often doing. Or we go to them looking for political violence, and if they’re not talking about political violence then we may ignore everything else. But in doing that, we missed stories like Emily Jeter’s — her stand, her telling the man to let her go, her recognizing who he was under the mask and telling him to let her go. So you see a lot of that in the record, but you also see people running away, which I think is a perfectly normal human response to what people understand is deadly violence. There are plenty of people in their communities, and sometimes even within the space of a same attack, who lose their lives. So there is no one way to respond; there is no one way to survive deadly violence. That they survive, I think, is one of the things that it’s important to sort of help people understand — to understand that they live, but they’re also going to live with what happened to them, and every different person who experienced that violence is going to experience it in a very different way. So, as educators we have to be aware of that and help our students sit through the reality. What might it take, you know, what may happen to someone like Emily Jeter? What may she learn from that attack? What might she do with that attack? Mitchell Patterson: One of the things we’ve been exploring in this series is really this long arc of the Black Freedom Struggle. So much of what you’re saying today about Reconstruction resonates with what’s happening today — racial violence uprisings, we’re seeing resistance in all forms. And it doesn’t seem like it’s that long ago. So, can you talk about some of the parallels that you see between Reconstruction and today? Williams: I think there are a lot. I think a lot of us don’t recognize the hold Reconstruction has over us today. Today, we see similar examples of victims of police and vigilante violence, and often experiencing similar physical and psychological injuries. They’re also being gaslit and discredited for speaking out about this violence, for resisting it. We see questions about whether or not you know who is deserving of citizenship rights and protections — many of the citizenship rights and protections that were bestowed upon all Americans formally during Reconstruction — and yet here we are having new discussions about birthright citizenship, and even efforts to denaturalize naturalized citizens. So, some of the same battles that were fought during Reconstruction are still being fought today, by people who were trying to take the nation back to an earlier time period when fewer people were able to enjoy the rights and protections of American freedom and American democracy. What you also see is a continuance of a campaign for Black life. Some could argue that earlier Black Lives Matter campaigns happened during slavery, as part of the larger abolition movement, as part of the movement for free Black people to get citizenship rights. Then certainly that movement of African Americans who are protesting the war that’s being waged on their freedom during Reconstruction. That in and of itself, I think, and protests again lynching are earlier Black Lives Matter movements. So you see a continuance, unfortunately, the reality that freedom for Black people is never ending, is an ongoing struggle and process. Mitchell Patterson: What are some good strategies for using these testimonies, these firsthand accounts, primary sources — assuming we’ve gotten age appropriate ones, for our students — what are some strategies or places, or other resources? The Teach Reconstruction campaign has plenty of resources, but what are some other archives or places that you might suggest that we go to find these firsthand accounts. There are many in your book, They Left Great Marks on Me, but please share with us. Williams: I would say, for example, with the stories, with the testimonies before Congress, one of the things that’s really revealing about them is a lot of them are quite long. While they are telling about them being targeted by vigilantes, what’s really interesting is that they’re also telling at the same time what they’ve done with freedom, what they have accomplished. So you can get a sense of how those are the things that are going to be what brings violence to their door. It’s not because they have failed, it’s not because they were accused of a crime — it is because they have made the most of American freedom. So, that’s one thing to do with reading the sources to understand the fullness of Black life, the fullness of Black people’s lives, their interiority, what they’re doing with or not even interacting with white people. That’s one of the things I think you can do to flesh out the complexity of the stories. There are letters African Americans write to the NAACP, which are available in the NAACP records. And many of those have been digitized. There are letters African Americans are writing to the President of the United States, or even to the Department of Justice. One of my favorite people is a woman named Mrs. M. Cravath Simpson, and she is a club woman. She’s the president of the Anti-Lynching Society of Afro American Women, and she writes this blistering letter to President Taft, essentially dressing him down for failing to protect African Americans’ 14th amendment rights to due process and equal protection under the law. So, I think even writing letters to the President as a club woman from the north, is part of that resistance to this violence. She is a woman in New England, but she sees herself as tied to African Americans in the south and willing to use her privilege as a woman who’s not living under the threat of violence to protect those who are. There are a variety of records, there are personal accounts, there are diaries, there are journals, there is fiction, there is poetry, like Paul Laurence Dunbar’s “The Haunted Oak.” The anti-lynching plays. All of them provide a way to help your students understand what’s happening with his violence, and a variety of African American resistance to it, if that makes sense. Mitchell Patterson: Oh, it absolutely does. And the few minutes we have left for this portion, what would be your pitch to teachers on why it’s important to teach this complexity, and why it’s important for young people to know these deep ways of resistance and the varied ways of resistance. Williams: I think that if our students understand Reconstruction then they can understand the world that we’re living in today, they have a context for what’s going on. That’s one. I think that if Americans who believe in liberty and justice are going to honor our national creed, then we have to stop this and other forms of violence, especially against Black people. But for that to happen, we have to know this larger history of Reconstruction. We have to complete the project of American freedom. And we have to do the work to try to undo and address the violence that placed and keeps African Americans outside of the protections of American freedom and democracy. So, I believe that this history is important not only because it helps us understand the world in which we live, but it also gives us an opportunity to help our students think through how we build a better world — because that’s what African Americans were trying to do during Reconstruction. Mitchell Patterson: The complexities of freedom-making and freedom-taking. I am taking that. I will give you all the credit but when you see it on Twitter, know that it’s us from the Zinn Education Project, because we just love that. Okay, everyone, thank you so much for that great conversation, we’re going to come back, so do not drop off. I did want to start with the lost cause, which is a narrative that is presented very heavily in textbooks. Can you speak to us about the lost cause narrative and some of the challenges with that? Williams: I think that the main thing to be able to understand for yourself and to help students understand is that it’s a fabricated history. But you can’t stop there. You have to be able to explain and help students see what the lies, what the fabrications, work in service of. So in this way, the lost cause narrative erases the history of Black military service. It erases the history of Black people establishing schools and churches, mutual aid societies, their own businesses. It erases that freedom-taking and freedom-making people. You can only get that history that they celebrate if you erase the Black people from it, or you turn them into these caricatures of Sambos and Mammies who only love white people. Right? But again, you can’t stop at that. I tell my students and they get mad at me, “It’s a lie. It’s a kindergarten take.” Right? Especially at the college level, right? At the college level, we’re going to level up, and what we’re in part of that leveling up means we have to understand what the lies do, the kinds of stories they allow white supremacist to tell themselves about Black people, about the nation, about Reconstruction, about the history, etc. And so again, that is the history that erases, that intentionally right out of the story, this freedom-taking the freedom-making people and it also allows them to erase the barbarous violence they unleash on Black people, for doing everything right. So we see them not only create all of this mythology around the South while they’re in the process of denying people all of the rights and opportunities and trying to erase what they did. So that’s point one. And part of that erasure of racist things like African Americans’ role in establishing a larger public school system throughout the South — which existed in the north but not necessarily the South before the war — not across the region. But African Americans played a significant role in doing that work. And when they drive African Americans out of office, they keep the schools and kick the Black people out, or starve them of resources. That’s a story that you don’t get. Someone asked a question about hope. So, African Americans are furious about not only the loss of rights, not only the violence, but the nation’s betrayal. They’re furious about that. But these are people who had made and taken freedom, and they did what they could to hold on to their institutions, to their people, to their land, to their families, to this dream of Black freedom. I think it’s important because we have to understand what’s happening in Black families and homes that will allow people like Ida B. Wells, Paul Robeson, Mary McLeod Bethune, Madam C. J. Walker, [and] James Weldon Johnson, to go out and do the things they do in the world, and to shape the world for Black people, and to lay another track on the foundation of the freedom struggle. So even with this violence, even with this history, Black people didn’t turn their backs on freedom. They continued to move in that direction, fighting for it wherever and however they could. They are the ones who made a way for what will become the Civil Rights Movement. If they had just sort of packed it up and said, “We don’t believe in freedom anymore,” they wouldn’t have produced children and grandchildren who went out and remade the world. So if you’re looking for that story of hope, if you’re looking for the inspiring story, I think that’s part of it. African Americans in 1850, they had no idea the Civil War was coming. They had no idea that emancipation was just around the way. And technically it wasn’t, and it probably wouldn’t have happened if they hadn’t taken the action they did during the war — because that’s how they make and take freedom. They’re not sitting, waiting for people to come and free them. They are taking advantage of the context of the war in order to fight for that for themselves. And when they get it, they move in the direction of forcing the nation’s hand to bring something akin to justice after slavery. And they see that as being in the form of rights. Mitchell Patterson: This freedom making and freedom taking, I can’t get it out of my mind. Can you speak about these advances that Black people were making? And then also juxtapose that with what you talked about earlier, it being called a failure. How does that framing go against each other, intersect, and come to speak to these advances that Black people are making? Williams: When people talk about the failure of Reconstruction, when I said earlier that they were essentially saying that Black people failed to make freedom real, which is not true. African Americans, they reconstitute their families as much as possible. They established schools in their communities. They’re creating schools before the Freedmen’s Bureau showed up in certain instances, before missionary societies showed up. That’s how much they believe in education for themselves and for their children. They are establishing churches. So, they’re seizing what Nicole Myers Turner calls “soul liberty.” They want religious freedom, religious independence — and they get that through their churches, through their mutual aid societies, they take care of themselves and their people as much as possible. They also want to become things like doctors and lawyers, and some of them are managing to be able to do that. Not many, but increasingly more of them are. And so those are some of the successes. They run for office — they don’t just vote, they run for office themselves. And in a number of cases, they win up and down the ballot, where they’re seizing authority in governance. As long as they have the vote they can continue to win that policy for the people in their communities, for the people they care about. But all of that richness, all of what they managed to produce, and even they’re forcing the nation’s hand to try to recognize their right to have rights through the Reconstruction amendments and the Civil Rights Act. That’s a significant achievement. If they hadn’t done that then there wouldn’t have been a basis for what will become the Civil Rights Act of 1964 or the Voting Rights Act of 1965. You can’t get that. Essentially what we see them do in the ‘50s and ‘60s is continue to point back to the 14th Amendment, the 15th Amendment, the 13th Amendment. When Martin Luther King Jr. says, “We want what you put on paper,” he’s talking about that Reconstruction legislation and those amendments. That’s part of the larger story of what African Americans produce — they produce a better democracy, a more expansive vision of freedom, for not only themselves but for all Americans. And so I tell my students, “If you’re the children or grandchildren of immigrants, you have birthright citizenship, in part, because of what African Americans helped achieve during Reconstruction. If you are arrested, you should have your right to due process and equal protection under the law. And if your state’s won’t uphold that then the federal government is supposed to make sure that they do. You have that because of what African Americans pushed for, what they insisted upon and their allies helped them achieve during Reconstruction. Mitchell Patterson: We had a question from the chat that said, “Can you talk a little bit about the role of the federal military in the South in advancing freedom for Black Americans and the impact of removing the federal military from the South in the late 1870s?” Williams: That’s an excellent question. The U.S. forces play a significant role; they become a liberating army with the Emancipation Proclamation. We know that. Where the Union army goes, the Emancipation Proclamation is actually enforced, because Confederates don’t recognize that Abraham Lincoln is their president. So when the Proclamation is issued, they’re like, “He’s not our president. We don’t have to pay attention to him.” They continue to hold African Americans in bondage, and people are able to enjoy their freedom there. If they can’t make a run for it, then they need to wait for Union forces to come into their community. So, the federal troops played a significant role in liberating people from slavery. In the Reconstruction period, their presence can play a role in enabling African Americans to enjoy freedom. But there are a couple of really important issues at play there. For one, the slaveholding South is a huge region of territory that the American forces cannot cover completely — they can’t blanket the region. So, what you often have are these army outposts that may be 40 or 50 miles apart. So if you happen to be five miles away, then you’re in good shape, but if you’re 20 or 30 miles away, then it may be harder to have your freedom recognized, or you may be more likely to experience emancipation reprisal. What also happens during this period is white southerners, former Confederates, their main thing is to get the federal troops out so they can essentially get back to doing what they had been doing before the war. They start to raise what they argue are these valid questions about being occupied by the federal troops, and they start to raise questions. Are we at war? Are we not? If we are at peace, and we have stopped fighting, then federal troops occupying this region are illegitimate, and there are people in the federal government — there are Democrats, Northern Democrats and Western Democrats — who say, “Well, actually, they did stop fighting. So why are there federal troops there? Let’s get back to states’ rights.” So, there is this pressure to withdraw the troops; a lot of it coming from the ex-Confederates themselves who are doing what they can to try to get back to the world they had made before the Civil War. Then there are these other people throughout the rest of the country, other white Americans, who are looking to sort of move on, move past the war and move past Reconstruction. So, this is part of why you start to see that diminishing footprint of the federal government, and a lot of the men in the army have completed the terms of their service. And even if they’ve extended them, they can’t extend them anymore. So the war is over. How do you justify a new draft? So there are all of these diplomatic, all of these military issues, that are at play. But what we know is that where the federal troops are removed, that’s when you start to see more violence. General Grant, once he becomes president, he is going to try to beef up the federal presence in certain areas, but they’re just not going to be able to stop all of the violence from taking place. Mitchell Patterson: Thank you for that very thorough answer. We had another question from the chat, “Can you speak about the connections between teaching and learning the history of Reconstruction, and current and early efforts towards reparations?” Williams: I think that’s a really complex question, and we only have a few minutes. I think it’s a great question. I think it raises questions. For me, it’s a question of different kinds of reparations. And, I have so many, so many responses to that. What can you do to provide justice after enslavement? What can you repair? I don’t know that land replaces a child who was stolen or sold away. So, what we know is that what people wanted was land. But then it raises all of these complicated questions — questions that people who are smarter, who thought this out better than I have, especially in terms of reparations. I think that we have to think about, or I’m more interested in thinking about what justice looks like, then and now, because we live in this future created by slavery and its afterlife. There are a lot of ways to try to repair or to move in the direction of justice. Some of them are financial, some of them are about education — like the Zinn Education Project — doing a better job teaching the actual history in the schools. But what’s really interesting is how resistant people are to even that. If you say some of the people who are opposed to reparations, financial reparations, say no to financial reparations, these are also some of the same people who will say no better education about the harms of racism or about Reconstruction in K through 12, either. Mitchell Patterson: That was right on point, because like you said, all of these things are complex, and we can go down several avenues. We also want to pose a question to the chat as well, because we had several questions about strategies for introducing images and depictions of racial violence. Like when should that occur? Is it appropriate or is it not? And we know that we’re in a virtual room of lots of educators that would have a response to that. So, we thought that it would be ideal if you wanted to say something about it. By all means, Dr. Williams, we’d love your insight as well. But we want to pose that to the chat. How do you introduce images of racial violence? When do you think it’s appropriate? We welcome our participants to answer that question as well. Williams: I’ll just quickly add, are images the only way you can teach this history? And I don’t know that they are. But I think that requires a little more thoughtfulness and a little more thinking about what we’re doing and why. For African Americans, for victims of this violence, they are trapped in debt in their worst possible moment. So there are ethical questions in my view, about when, why, and how we use images to teach this history when there are letters, when there are newspaper reports, when there are a variety of other sources to teach this. It’s not to say that I’m completely opposed to images — I question when, why, and how we use them, and what’s appropriate, and what kind of preparation you give students for dealing with this history. Too often, this history is taught in an unthinking way, in an insensitive way, in a way that’s indifferent to the harm that could happen, and I think we as educators need to be aware of that. But for those of you in the upper grades, with you all, I would encourage you to ask your students how many of them have seen these images already circulated on social media. Mitchell Patterson: Then and now. Williams: Exactly, and in what context, what they thought, what they do, what they think should be done in terms of how this material is taught. Mitchell Patterson: I think that’s a very powerful response, particularly giving our students that agency, as well to have that very clear discussion on the ways in which they have learned this. We want to be sure and be mindful of how we do this work — it’s powerful work, and it’s something that we must take great care in. I thank you for constantly reminding us of that, because it’s so important. Someone mentioned about, “Is there a way to filter histories by region?” I do think it’s important that we think about how these stories are also localized for our students and thinking about utilizing their local libraries, and how there may be stories within this period that you can bring into the classroom. Can you speak to local histories a bit? Williams: Absolutely. And I would say to those of you who are in the north and west, you should definitely look into the local history. Because the history that you think is there is probably not there, given the fact that there’s going to be such widespread resistance. Like Michigan, I’m in Michigan. Michigan, for example, said “The 14th Amendment shouldn’t apply to us since we didn’t secede.” Other midwestern states said “The 15th amendment, no Black people shouldn’t vote here, don’t punish us. Why are y’all trying to mess with this good thing that we have here?” I love the idea of looking at your local history to get a sense of what happened during Reconstruction. I think that that will also give students a better understanding of what happened and the fights that occurred over it, and to understand that Reconstruction isn’t only something that happens in the South, it happens in the north, it happens in the west, too. California votes against the 14th and the 15th Amendments, against both. There’s a great book out by Stacy Smith called Freedom’s Frontier that looks at what’s going on in California. There’s a whole lot, y’all, but California isn’t the only one. So, I really do think it’s important to look at those local histories, and not just in the South. That might be a more enlightening way to teach Reconstruction than only focusing on the South. Not necessarily to the exclusion of the South, but to give students a better sense of the complexities of what’s going on in terms of resistance to Reconstruction, [and] what Reconstruction in the north and west looks like in comparison to the South. I did get a question in the chat that I just want to answer quickly, if that’s okay. “When did I start to see Reconstruction this way?” It wasn’t in K through 12, let me assure you! I really started to get it once I started to take college level classes and African American history classes that walked us through this. And I saw that there was a richer history there. After getting that I could never look only at the fights in Congress and the president. In fact, when I go to conferences and that’s all they’re talking about, I just want to pack my bag and leave. I’m like, I’m not interested in any of this. I mean, I am, I know the history, but I’m much more interested in what ordinary people are doing in order to drive this policy, or in order to live with or respond to this policy. Mitchell Patterson: Thank you, thank you, thank you. We cannot thank you enough for the time that you have given us. While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Transcript

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

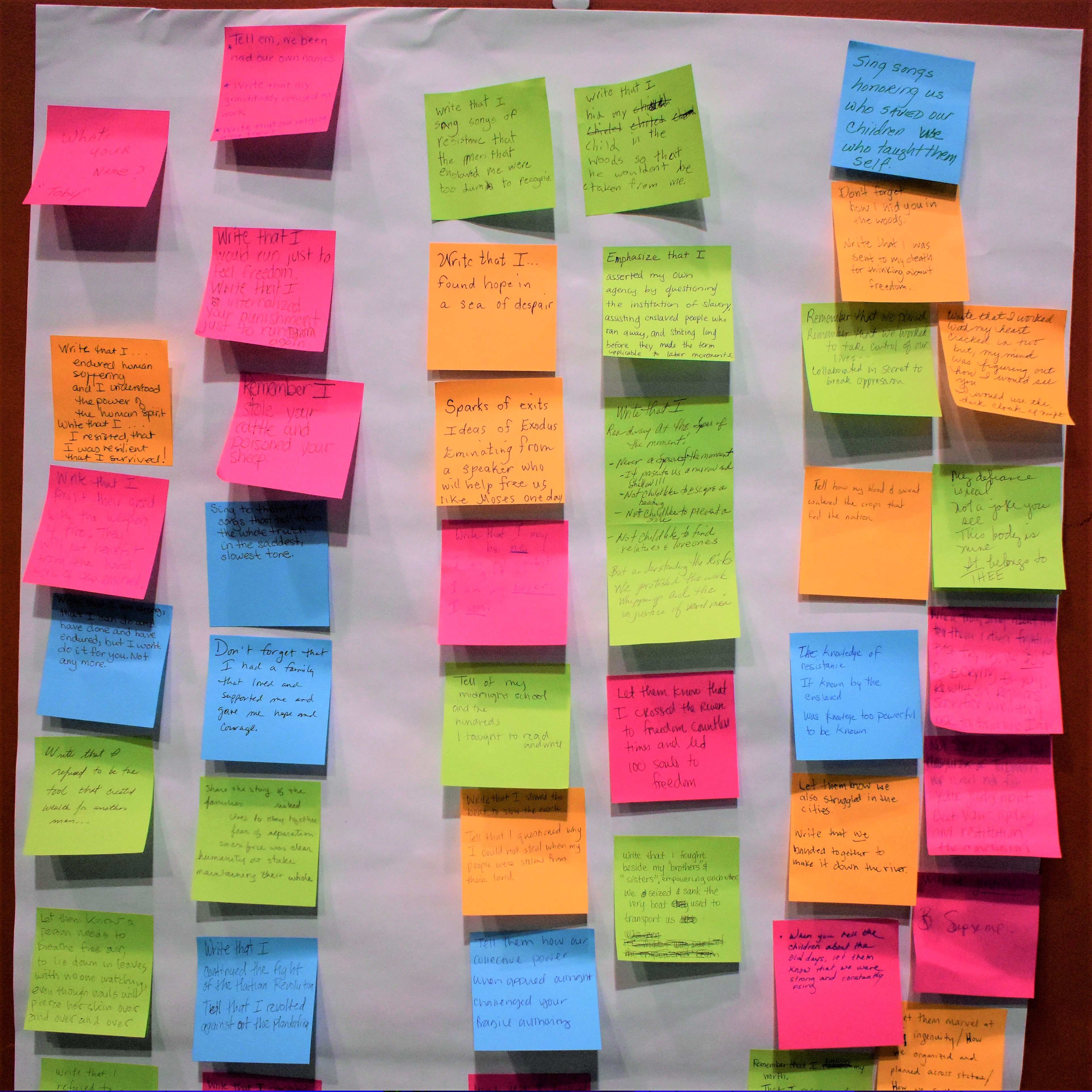

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was learned

Responses to the question: What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today and what may you do with what you learned?

Freedom-making/Freedom-taking! I’ll continue to study more about Reconstruction.

Reconstruction didn’t fail; it was violently overthrown. Black people did *not* fail at emancipation.

Reconstruction touched all Black people including men, women, and children. This should be taught holistically and with acknowledgment of the bias of our individual point of view. I’ll study Reconstruction myself so that I can teach it to my students with accuracy and conviction.

For me, it was great to learn about this important time of history. I appreciated the focus on testimonies and acts of resistance. I will start doing my own research to see if I can construct an age-appropriate way to teach this in 5th grade.

The class revealed resistance to the racist violence that too often buries Reconstruction in monochrome. As a newly retired member of the North Carolina Association of Educators (NCAE), I want to help bring our discussion into teaching practice and curriculum transformation by its newly elected leadership.

Being sure to include resistors when you teach about oppression, and to look into local history. Not quite sure how I will use this in math yet!!

Living what whites would consider a “normal” life WAS resistance. I have to teach more about what most Black people were doing during the Reconstruction period.

Wow! There is so much — freedom making and freedom taking and the different ways that people resisted. I’ll be more thoughtful before presenting material that may be traumatic to see/hear. Also, I’ll use first-person narratives — making sure to spotlight the voice of women, children, and the disabled.

The use of narrative over images in teaching a topic I want to build a Reconstruction unit for my course — as U.S. History, we skip Reconstruction and start with the Gilded Age instead.

“Freedom making and freedom taking” — the magnitude to which slaves and freed slaves were responsible for emancipation and the success of Reconstruction I will continue to think of ways to integrate Black history into the K-5 curriculum.

“Reconstruction didn’t fail, it was violently overthrown” — that comment and then thinking about parallels with post-civil rights movement and COINTELPRO, and potentially what happens in response to Black liberation movements today; also the specific examples like the 8-year-old who called out her white attacker by name to prevent him from attacking her. I’ll continue to incorporate into the framing of history to my students.

I learned in my breakout group that there is a Reconstruction nonprofit in the Sea Islands of South Carolina. That’s exciting for me. I am thinking a lot about how to use images in my classroom but I was also focused on the community violence aspect of the talk — that people knew the folks who were trying to steal their freedom.

“Freedom making, freedom taking!” I want to juxtapose Reconstruction narratives about the South with local history in California.

Talk about agency more in class! I am going to continue to incorporate more stories into my everyday teaching. I am also going to create a specific lesson on Henry Adams.

Dr. Williams’ push to go deeper on simple takes like “oh obviously it’s a lie,” re: Lost Cause Narrative and other attempts at erasing real history. I found it a really important strategy (“that’s a kindergarten take!”) to go deeper on the discussion with my high school students! I’m planning on trying new questioning strategies — like the one above — asking students to bring in their prior knowledge, bring in more testimony primary sources, and ask students to reflect more deeply on the agency of Black people during/after Reconstruction.

The idea that Reconstruction is a difficult, sensitive topic that must be taught and isn’t always taught correctly. It will inform future units that I do relating to civil rights and black history.

You cannot understand Reconstruction violence without understanding what the Black community felt it was doing to them. I will apply it to future coursework and use it to change my perspective of Reconstruction

The importance of personal narratives and the history of racism in California. I’m looking for ways to incorporate Reconstruction into my English curriculum.

I’m retired and will teach a class on African American history for my church.

Identify the fabrication in oppressors’ history, but DON’T STOP THERE! I will continue to push for more time to teach Reconstruction

I want to teach the actions of African Americans that drove the policy changes, and how people responded to the policies. This will help me focus on the strength and resilience of African Americans instead of the traditional white savior messaging.

I was particularly struck by the account of the young girl who recognized the man who was attacking her. Her ability to speak out showed a level of strength and resistance that would really stand out to my students. It also demonstrated that the violence so localized and so personal which makes it feel more real. I want to teach Reconstruction from a people-first perspective. I want to teach about the stories of success, and the ways white supremacy was used to push back. Freedom makers and freedom takers — quote of the panel!

I appreciated the stories of the Reconstruction era that I had not heard. The reminder that the narrative is biased, even in the telling of successes. I have been and will continue to push my school and district to require teaching Reconstruction in US history. The tools gained today will help to make the case and also helped to provide me with additional resources.

FREEDOM MAKING AND FREEDOM TAKING! And going against the grain of our archival work. Teaching students how to read between the lines of artifacts and move beyond the “lost cause” narrative. This will impact my instruction by giving me: 1) Being more conscious about the images we use (how when and why). 2) Framing for how I teach Reconstruction. — FREEDOM MAKING AND FREEDOM TAKING! 3) Challenging older students to identify lies and asking kids who those lies serve.

The importance of primary resources and researching Reconstruction in the Midwestern and Northern states. I will dig into some of the other resources.

Ideas for how I can better present truths about Reconstruction to counter the narrative that is so prevalent. The idea of how this continual fight for freedom keeps thriving–how the work of those in Reconstruction was not lost but led to the work and people who kept — and keep — making changes. My state is working on standards right now and we are in the feedback session–I will make every effort to argue for Reconstruction to be taught more fully and stories of resistance to be framed as patriotic and necessary to build a true democracy.

“Can you ever repair the harm of slavery?” That the testimony of people who survived terror talk about it in the present tense, the trauma is now not in the past. I’m working in a movement within the Episcopal diocese and churches to dedicate funds for reparations.

Dr. Williams encouraging the teaching of local histories, i.e. outside of the southern states, esp for educators located in the north and west – terrific suggestion – thank you Dr. Williams! continue teaching Reconstruction as the radical experiment in interracial democracy it was; teach about its intentional sabotage by white supremacists; always emphasize Black folks’ agency, and continued resistance to build new systems and self-determination for themselves and all people

The testimonies that were given by Black people harmed by gang violence, WOW. To be bold enough to testify in court to the injustices forced upon you at that time is a testament to the strength of Black people. I will add this book to my classroom library for sure. We just want to live…simple as that.

The eyewitness testimony was a validation of things that I do, but the focus on PRESENT tense, implying both hope and impact, was a powerful addition. I also loved Dr. Williams’s questioning of images vs. letters in Reconstruction lessons.

We need to center the words and voices of newly freed Black people — available in archives as letters, journals, and other documents — and teach those as the narrative of record — and to rightfully replace the Lost Cause narratives that erase so much Black agency. Freedom taking and freedom making! I will look for and use some primary sources when I teach my unit on Reconstruction to my 4th graders.

I would state from an SEL standpoint to use other primary sources besides images due to the fact that we do not want to retraumatize descendants of assaulted individuals. I want to ensure that I approach Reconstruction violence with fidelity as well as showcase the last impacts with a higher level of sensitivity.

Dr. Williams affirmed the importance of testimony for me. I think that the combination of not shying away, but also delivering this curriculum with care is central to teaching Reconstruction and she is inspiring me to not shy away with love. I am supporting my student teacher to teach my month-long unit on Reconstruction in January. I think that focus on testimony will be central to this.

The format

Small group discussions were great and the facilitator did a great job. I loved that the groups were less than 10 people. We had just enough time to get through the two questions.

The format — Zoom — worked well for me. The breakout sessions were informal with great conversations.

Great as usual! I think the questions today for the breakouts were spot on.

Many historical professional developments do not feature breakout rooms so it was helpful to have that addition; thank you!

It would have been nice to talk even longer in groups, but otherwise, I think everything worked perfectly! The Zoom call was run so smoothly, the facilitation of small group discussions, & the conversation with Dr. Williams was excellent. Tiffany Mitchell Patterson’s questions were so thoughtful and insightful — she did an amazing job at leading the call.

Loved seeing the comments in the chat! I honestly learn so much just from reading that.

It was great that people could add questions to chat. The length of time was incredible to hear Dr. Williams talk and just drop knowledge the way she did!!

I thought recollections of how Reconstruction was taught worked really well. I might have had a second breakout at the end to allow the session to continue and to review what struck different participants most.

It was nice to connect with people in the breakout room, and I thought Dr. Patterson did an excellent job facilitating the conversation.

I was so inspired by all of it — I appreciate how well planned it was. I could have spent hours with the beautiful people in my breakout group, but the facilitator did a nice job of keeping the conversation flowing.

Breakout groups and questions helped build community and reminded me of how little most people learn about Reconstruction in school.

This was so incredibly well-executed. Tiffany Mitchell Patterson was an amazing moderator, and Dr. Williams managed to share so much in so little time. Thank you both! I appreciated the opportunity to hear from peers in the breakout room.

I liked everything. I think since these types of events are likely to get people who are truly interested in learning about the subject being taught that they could even be a little longer so the group discussions can go longer and get more in-depth.

Loved the format conversation with the historian. It felt like she was talking just to me.

I like that the bulk of the presentation was in the form of a conversation and not just a speech, and supplemented that with the chat-box for questions and conversation.

Additional comments

Thank you!! This was such a thought-provoking class — it was my first one, but I’m hugely inspired to return for future classes.

This was an awesome way to spend my Monday evening! I love being around like-minded people who are working and studying to learn the true authentic history of our country. Only by self and group study can we make changes. I really want to see the education system change to reflect the diversity of our country in ALL subjects not just history. Thank you Zinn Project for creating this space to learn and become energized for my next unit.

Thank you for these seminars. I hope that you continue them even when the pandemic no longer prevents us from meeting in person.

Thanks to everyone for making this possible. I’m going to encourage my organization to make use of this and other ZEP trainings.

I am very tired (virtual teaching is no joke) but I’m so glad I Zoomed in this evening.

Awesome discussion. Hate that I could not stay until the end. I learned a lot and I am re-energized to dive into learning more about Reconstruction.

Thanks so much for yet another stellar session. Dr. Williams was phenomenal — and I’m looking forward to Jeanne Theoharis next month.

Thank you very much! It’s amazing to get together as a community to educate ourselves and to strive for change.

Thank you! This is my first Zinn class/webinar/PD and I almost bailed because I am so tired, but found the discussion, information, and format very engaging!

Thank you! In all sincerity, this has been the highlight of my fall semester.

This was so great! Made me realize that there is so much that I do not know. Looking forward to learning more through Dr. Williams’ book.

Presenters

Kidada E. Williams researches African Americans’ experiences of racist violence. She teaches courses on African American and American history and historical research methods at Wayne State University. In addition to research and teaching, she gives lectures and talks at public institutions including the Wright Museum, Detroit Historical Museum, the Henry Ford Museum, and America’s Civil War Museum. She contributes to NEH Summer Seminars and Institutes, which help K-12 teachers broaden their understandings of U.S. history and develop new strategies for teaching challenging subject matter. Williams is also one of the co-developers of #CharlestonSyllabus, a crowd-sourced project that helped people understand the historical context surrounding the 2015 racial massacre at Charleston’s Emanuel AME Church.

Tiffany Mitchell Patterson is an assistant professor of secondary social studies at West Virginia University. She taught middle school social studies in Washington, D.C. and Arlington, Virginia and is a Teaching for Change board member. Her articles include, What everyone should know about Reconstruction 150 years after 15th amendment’s ratification.

Learn more in the Zinn Education Project national report, “Erasing the Black Freedom Struggle: How State Standards Fail to Teach the Truth About Reconstruction,” and find teaching resources on Reconstruction below.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn