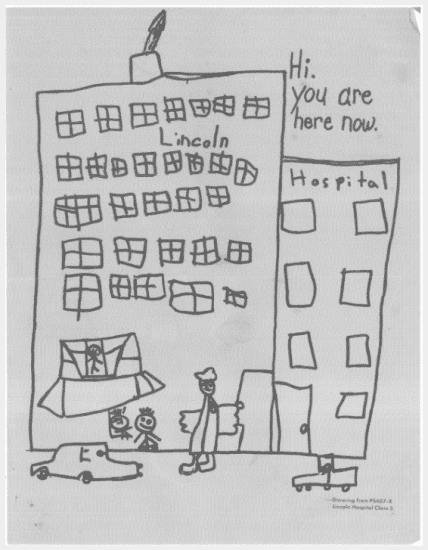

Drawing by an elementary school student for the cover of the Lincoln Collective’s recruitment pamphlet.

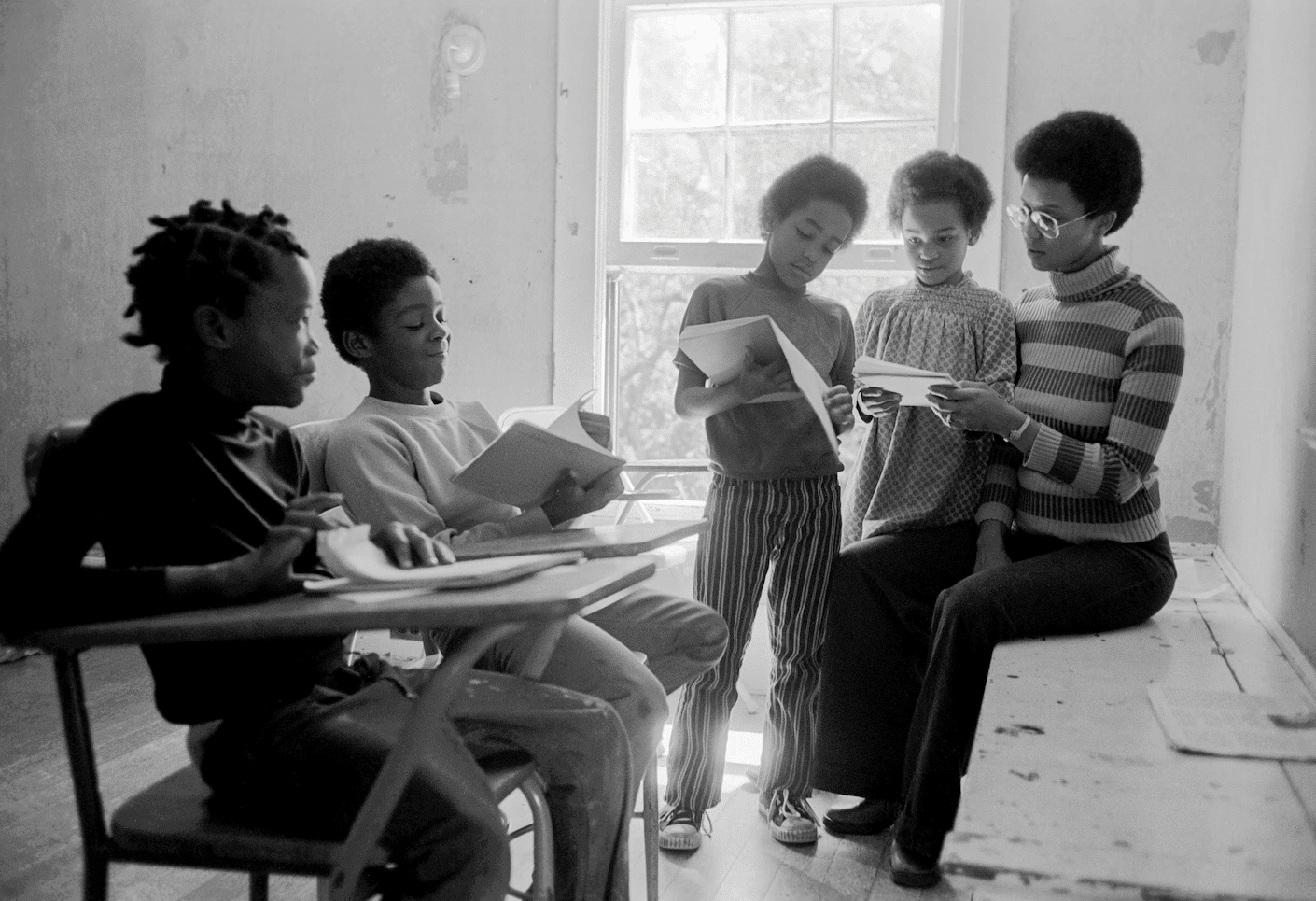

During the 1960s, medical students in the United States, like other young people around the world, questioned the structure and content of their education.

Many of them also participated in the movements against the Vietnam War and for expansion of civil rights. They disliked the rigidity of their medical studies, and they wished to confront the racism and class prejudice they found in hospitals and medical careers.

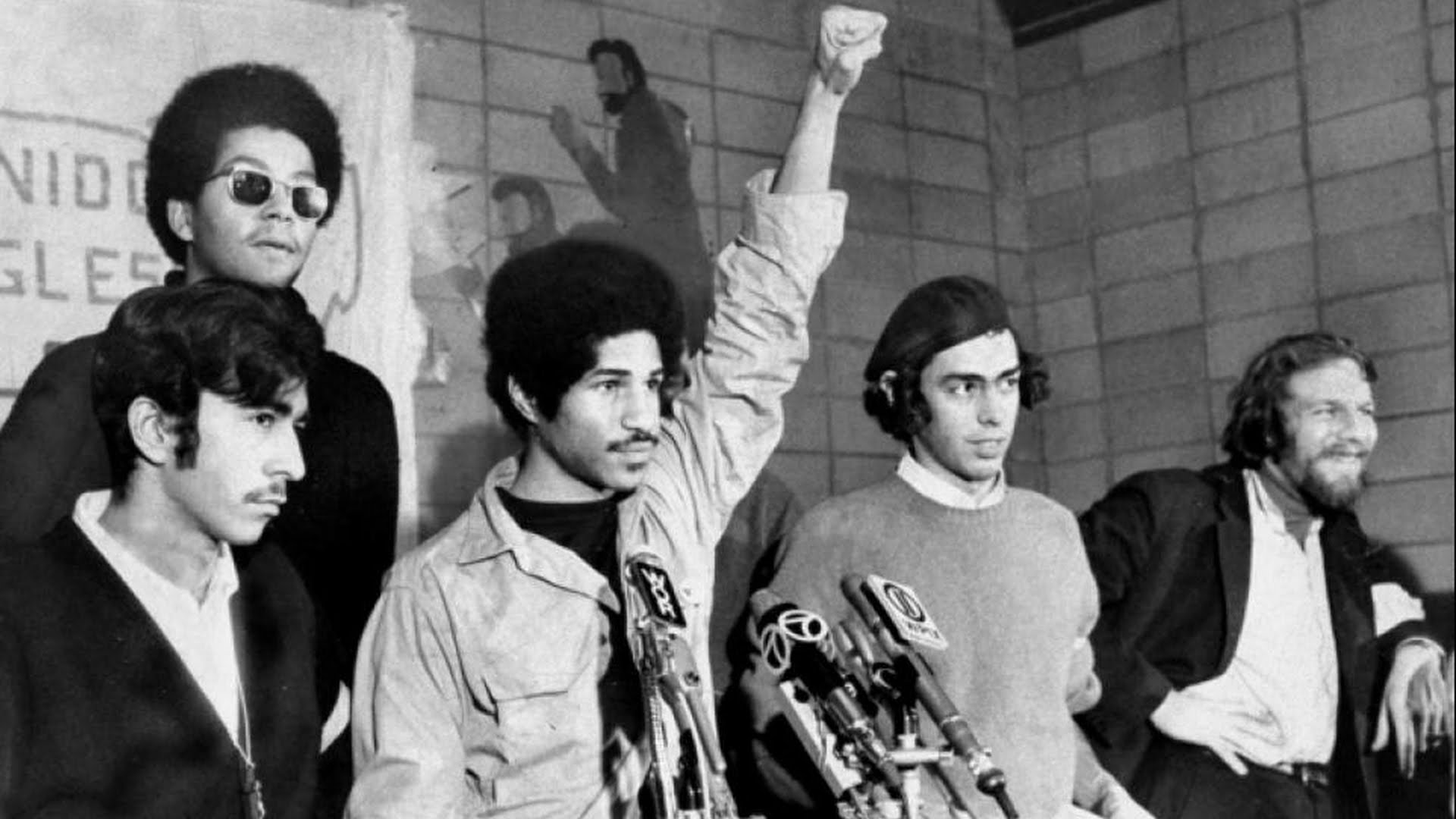

On July 1, 1970, over three dozen recent medical school graduates rejected the path toward elite, professional advancement in a coordinated way. That day, these young doctors showed up as a group to begin work and post-graduate training at Lincoln Hospital, a run-down, underfunded public hospital in the impoverished South Bronx section of New York City. Some had previously shared an activist history since 1965 in the Student Health Organization. Some had more recently reached out to the local Health Revolutionary Unity Movement (HRUM) or the related “Think Lincoln” daily complaint table that recorded patients’ grievances and suggestions. They developed preliminary contacts with the local Black Panther Party and the Young Lords, a radical activist group of primarily Puerto Rican youth.

Calling themselves the “Lincoln Hospital Pediatric Collective,” these young doctors wished to develop a department where service to pediatric patients and the community would be the primary aim, rather than simply a minor by-product of an academic, residency-training program.

In the Collective’s initial days its members rejected the traditional privilege of taking their meals in a physicians-only dining room. Following the Young Lords’ one-day occupation in mid-July of the Hospital’s main administrative building — a protest against the poor conditions at Lincoln — the Collective collaborated closely with HRUM to develop and publicize fundamental principles of medical practice, such as:

- doctors must always introduce themselves by name and address the pediatric parents appropriately;

- they would individually commit to continuous relationships with patients and their families, including participation in weekly appointment clinics that took precedence over most in-patient responsibilities;

- there would be a doctor’s “night-float” system on the wards and Collective team-members would regularly back up one another for emergency coverage.

A “Patient Bill of Rights” was developed by HRUM with Collective input. These principles were unusual for hospitals and training programs in that era. Some of these innovations have since become standards of practice, but more improvements are needed.

The Lincoln Pediatric Collective also addressed the training program’s academic content, giving attention to common problems such as ear infections and asthma, as well as “diseases of oppression,” such as lead poisoning. and examining the institutional, racial, class, and cultural determinants of health care. It called for democratization of administrative responsibilities which had been traditionally reserved for the Chief of Service.

By December 1970, antagonistic conflicts with the Hospital’s previous Pediatric Chief led to his departure. His replacement was Dr. Helen Rodríguez-Trías, a Puerto Rican pediatrician whom the Collective interviewed and warmly endorsed. She remained active as a teacher and practitioner at Lincoln for several years before moving on to distinguished leadership roles in public health.

This “this day in history” post was prepared by Henry Kahn and Charlotte Phillips for the Zinn Education Project. Henry Kahn joined the Pediatric Collective in July 1970, serving for one year. He later helped develop neighborhood health centers for Grady Memorial Hospital (Atlanta), taught at the Emory University School of Medicine, and worked at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Charlotte Phillips went to Lincoln Hospital in February 1969, and with others laid the groundwork for the Pediatric Collective. She stayed for seven years. She later worked as a primary care pediatrician in the New York public hospital system in Brooklyn. She also co-founded and serves as the chairperson of Brooklyn for Peace.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn