I greatly appreciated the audio and video elements of Paul Robeson that was incorporated into the discussion, really helped infuse the event with a true sense of the man himself. Dr. Carr’s encyclopedic knowledge was riveting and you just want to hear him talk and talk. Really great, thank you.

I really did not know about Paul Robeson before today, so the entire class was eye-opening for me. It made me question why it has taken me this long to learn about this influential American. I want to know why we are not teaching about Paul Robeson in our classes, so I want to discuss this with educators at my school site.

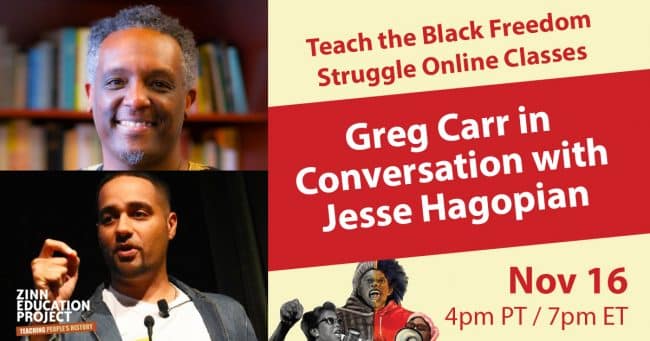

These are reflections from just two of the participants who joined the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle class on Paul Robeson, Political Outlaw: Lessons for Today from the Black Radical Tradition, featuring Dr. Greg Carr in conversation with Jesse Hagopian. Carr connected Paul Robeson’s life to contemporary political concerns by interrogating Paul Robeson’s struggles against fascism and for workers’ rights, his struggle against McCarthyism at home, and his wife Eslanda Robeson’s contributions to the Pan African struggle.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: It is so wonderful to be back online with everybody. This series got kicked off last spring in the wake of the pandemic, and big shout out to professor Jeanne Theoharis for helping launch this whole project. We had our first session a couple weeks ago and this is my first one back, so I’m really excited to be with you all this afternoon. I want to welcome everyone on behalf of the Zinn Education Project for our session on Paul Robeson. I think we’re all going to be deeply enlightened about his legacy this afternoon. Some of you are joining us for the first time and some have participated in our spring series. It is a gift to be able to share this time together and I want to thank you for being in this virtual community with us.

My name is Jesse Hagopian, I’m a high school teacher, an editor with Rethinking Schools, and I work with the Zinn Education Project helping to lead up our initiative called Teach the Black Freedom Struggle campaign. Rethinking Schools coordinates the Zinn Education Project along with Teaching for Change. The Zinn Education Project is hosting this session today and offers free downloadable people’s history lessons. We won’t sneak them under your door as we were charged with by the Trump administration, but we will make them available online for you to download. And many of you have used these for middle and high school classrooms from

the Zinn Education Project website. We have a campaign with many different components to teach the Black Freedom Struggle that I urge everyone to check out, and this class is part of that campaign.

Throughout the session we want you to use the chat box to post questions, comments, resources, ideas that you have about our topic [and] we will read your questions and then Dr. Carr will try to respond to some of them after the breakout group. We’ll do our best to answer as many questions as we can, but we’re not sure if we’ll be able to get to everything. We’ll do a short evaluation at the end so please don’t leave before you fill out the evaluation.

Now we’re ready to launch our conversation. After about 25 minutes we’ll pause so that you can meet each other in breakout groups and share your thoughts with one another. I am thrilled to introduce you to Dr. Greg Carr, who insists I call him Greg. So, I’m going to work on that. He’s associate professor of Africana Studies, [and] chair of the department of Afro-American Studies, at Howard University, and adjunct faculty at Howard School of Law. Carr is the co-founder of the Philadelphia Freedom Schools Movement and is an advisor with the Zinn Education Project’s Teach Reconstruction campaign. Welcome, Greg, I appreciate you being here.

Greg Carr: Yes, it’s a real pleasure, brother. I’m a longtime follower of your work. If you all are not familiar with that work, please, you’ve got to get the publications and you’ve also got to get into the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle series. It’s an honor to be with you, brother, and always with Deborah and the whole family. I’m looking forward to the conversation.

Hagopian: I can’t tell you how much that means to me. Thank you so much. Let’s dig into this. I’ve got to say, preparing for this interview has been so much fun, to read about Paul Robeson’s life again and listening to podcasts. I’m just so immersed in his world and I came across this incredible clip of an interview with Paul Robeson I thought we could start off with. Then I just want to ask you a question related to it.

I’m proud of being African. Now, in our school books they tried to tell me that all Africans were savages. Until I got to London and found most of the Africans I knew were going to Oxford and Cambridge and doing very well and I learned their culture. Even once somebody had the temerity — after one had conquered the Chinese people and imposed upon them the opium trade and everything else — to suggest that they were backward people, just the people who had been civilized so long over the rest of you folks. It didn’t make any sense at all. So, somewhere it was wonderful to find about the colored peoples of the world, that they were very advanced. I would say today that I’m an American who is infinitely prouder to be of African descent, no question about it.

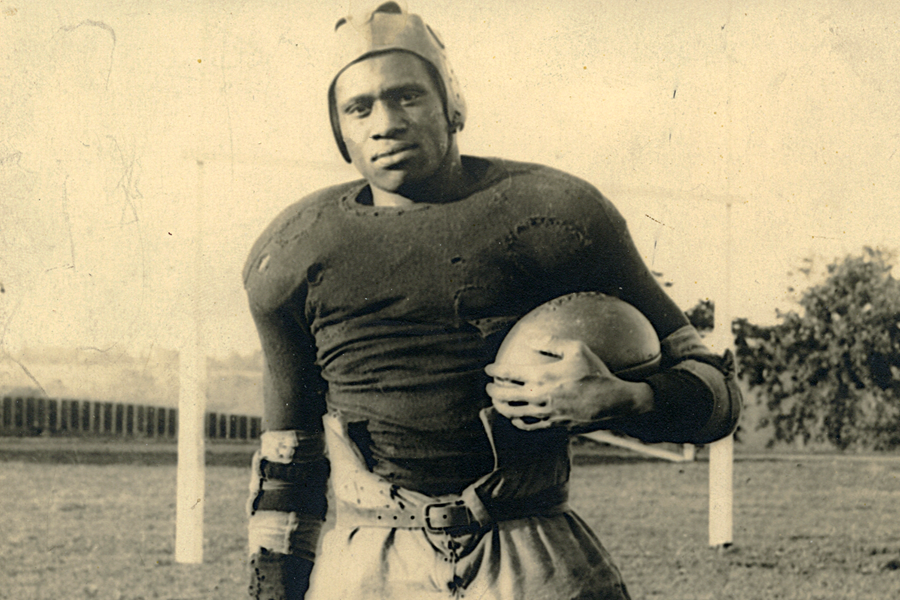

I just wanted you [and] everyone here to hear Paul Robeson’s beautiful voice and just feel his energy for a moment. To me, Paul Robeson is like the Black Paul Bunyan, or maybe Paul Bunyan is the white Paul Robeson because he’s just such a legendary, larger than life figure. He was valedictorian at Rutgers University, he was an opera singer, a stage actor, like Shakespearean stage actor, and Hollywood actor, a lawyer, he played professional football in the founding leagues of the NFL. I don’t know how many languages he spoke, including African languages and Asian languages. He was a leader in the Black Freedom Struggle, an anti-fascist, a socialist, a revolutionary. I just want to ask you, Greg, what happens to our kids in our schools — to history class, to art class, to music class, to social studies, and drama classes, sports teams — when Robeson is left out of the narrative of our country?

Carr: Jesse, first, thank you for playing a clip and for allowing that ancestor to open the way for our all too brief conversation tonight. I’ll keep my end of our back and forth brief because the beautiful thing about this technology is it allows us to go global — we don’t have to worry about Paul Robeson getting on a transAtlantic phone line to sing to the Welsh miners or standing at the Peace Arch in Washington state singing across to the folks in Canada, because everybody is here. As folks are introducing themselves we heard that there are a lot of people in this space who will be learning something about Paul Robeson for the first time and a lot of people who know a great deal about Paul Robeson, which is what makes this convening so important.

One of Robeson’s great influences — who he really looked up to, the famous picture of them shaking hands in 1949 at the Paris Peace Conference — W. E. B. Du Bois once said that one of the great tragedies in the world is that people don’t know enough about other people, and I think both Paul and Essie Robeson, his wife, his partner, really are two outsized examples of human possibility. What our young people, in engaging [with] them, get to see is two people who were human beings, who between their two bloodlines in terms of their families encompass the history of the United States of America as a settler-colonial project. But they encountered them as people who seemed like they couldn’t be real for all they did. They did it in a way that really allows us to see that we all have that possibility.

I think that’s the genius of the Robeson’s. That’s the genius of Eslanda, that’s the genius of Paul, when we just looked through a little bit of their lives. In fact, I’ll end with this. Again Du Bois writing about Carter G. Woodson. When Woodson passed he wrote one of the obituaries and he said this life shows you what race prejudice can do to a human soul and what it’s powerless to prevent. I think Paul Robeson and Eslanda Robeson show you this is what you’re up against but this is what you can transcend if you just embrace our common humanity.

Hagopian: That’s beautiful, no doubt. I’m reading this book, Paul Robeson: The Artist as Revolutionary, and I love that the first chapter is called The Best Known American in the World, and I just love that part where Time magazine called him “the most famous negro in the world.” Then they were corrected, that actually he was the most well-known American in the world. It just blows my mind how few classrooms teach about the most famous person that existed at the time in America and how he’s been erased.

So thank you for bringing him back and also for bringing back Eslanda Robeson. I mean, she is erased from the textbooks completely, as so many Black women in history are today. Yet she was a towering figure of her own right, an anthropologist, an author, an actress, and a civil rights activist. Can you just say a couple things about her? Then folks can read the book by Barbara Ransby.

Carr: That’s the one to get, Barbara Ransby’s book. She is incredible. In fact, when you played that clip of Paul talking it reminded me of her book African Journey. Eslanda Robeson writes about the fact that after they moved to England she said she and Paul went looking for all the Africans they could find. She said they went in the alleys, they went into universities, they went everywhere because she had started taking some classes, and she said in America we didn’t learn anything about Africa. She started with, “I wanted to go to Africa. It began when I was quite small. That’s where we’re from.” But then she says she was confronted by these folks in England saying, “Well you don’t know anything about the African. How could you know?” And she said, “Well this is what I feel. I am African,” and they said, “You’re not African, you’re European.” And she fought back with almost word for word what we heard Paul say in Australia. Essie is writing in the first two pages of African Journey, which is her travel log from traveling throughout central and southern Africa with Paul Jr. at the time. They’re organizing women.

Essie Robeson’s people come out of South Carolina. Her grandfather, Francis Cardozo, of course, has a school in D.C. named for him. They ran him out of South Carolina and they locked him up for a year during Reconstruction for advancing the rights of Black people. He ends up a major educator in D.C. Then, his daughter Essie’s mother is a brilliant chemist, which is what leads in some ways to Essie’s interest. She becomes the first chemist on staff at Columbia Medical Center and then, when she and Paul meet around that time, she decides to move from her career as a scientist to become his manager. She is really, in many ways, the reason we even know Paul Robeson in any way.

She’s the one who manages his career and then decides — after conversations with folk like Zora Neale Hurston in New York — I’m going to be an anthropologist. She’s writing book after book after book and so that’s that line. Then you match it with Paul, whose father escaped enslavement, you understand. I should mention that his father escaped and his mother actually came out of a line that produced his mother’s sister’s daughter, who is his first cousin, Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander out of Philly, whose people moved to D.C. so she could go to M Street High School, now Dunbar. This convergence of these two human beings, it’s almost like what can you throw against the human spirit and in response what can the human spirit do to demonstrate to the rest of us that nothing you throw at humanity needs to be endured if it’s oppressive.

Eslanda Robeson is remarkable. She finally makes the transition in 1965, and Paul lives another 10 years but in many ways, as their son Paul Jr. writes about and even their granddaughter Susan [writes], without Essie it just becomes that much more difficult to manage. She’s the glue. She is as much a citizen of the world as he is.

Hagopian: Thank you for connecting so many dots for me. Now I actually have to finish that book by Barbara Ransby.

Carr: Everybody’s in there! Barbara Ransby did a towering job on that. I should mention, we know about Paul Robeson, we’ll talk about that in a minute, when he had to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee [HUAC]. Essie Robeson had to appear before the Senate counterpart for McCarthy three years earlier, and she walked in there and one thing they first asked her is, “Did you write this book?” She said, “Did I write this book?” Oh, the shade she delivers. In fact, she says in this book, “I was actually working on something, on the Mau Mau when I was interrupted and had to go testify at the Senate meeting.” Anyway, that’s the militancy!

Hagopian: That leads me to my next question. I want to talk about this McCarthy era that they both lived through, and both were persecuted under. They faced extreme repression from the McCarthy era witch hunts and the HUAC. So, how does McCarthyism disrupt struggles for racial and social justice, both back then and in the modern day versions of McCarthyism that we’re struggling through today?

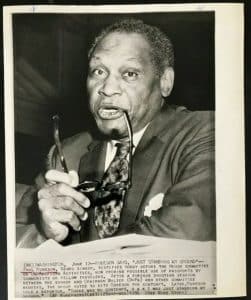

Carr: Jesse, man, when you mention that piece from Time that Gerald [Horne] quotes, it’s remarkable isn’t it, for this man to be one of the most recognized human beings in the world — arguably the most famous American in the world in the mid 1940s. Records ballot for Americans, does all this stuff. He goes on these USO tours and he’s doing all this work, and within the space of six [or] seven years goes from doing a hundred thousand dollars a year and being this huge patriot, NAACP gives a him a Spingarn Medal, to maybe making two thousand dollars a year singing in Black churches and being an enemy of the state.

He and his wife’s passports are taken. You put them with Louise Thompson Patterson and her husband, William L. Patterson, and his friends Shirley Graham Du Bois and W. E. B. Du Bois, they make them into enemies of the state. And that small group of Black bourgeois leaders like Roy Wilkins and them, they turned their backs on them.

I think it’s really the confrontation we face today. Anytime you see global solidarity movements the fascist elements — and he called himself, literally said, “I am an anti-fascist.” So, I guess if Paul and Essie Robeson were here today they’d be labeled antifa in some way. Which actually goes, I think, to the beginnings of our conversation around the question you raise which is: What happens when ultra nationalist movements, right movements which have infiltrated (as if they were ever absent) the apparatus of the state, feel threatened by those who picked our common humanity over anybody’s national or state interests, particularly finance capitalism? So, they had to come for them because at that time, as Gerald Horne writes other places, by the 1950s the world is shrinking, these anti-colonial movements are going, and the United States is in a competition to try to sway global opinion, to recruit some of these countries that are gaining and taking their independence onto their side.

They’ve entered the Cold War and Paul and Essie Robeson become casualties. They are attacked and they’re not only attacked by the apparatus of the state, by the government, they’re not only attacked by the apparatus of entertainment — whether all the bookings drop except in the Black venues — they’re also attacked by those who should be in solidarity with them. That’s what Peekskill is about in 1949. I mean, you look at Peekskill, where you got U.S. veterans fighting union folk, you’ve got this antisemitic move, this anti-Black move, and I’m saying is this peaceful 1949 or was this 16th Street Saturday night when everybody showed up and the police stand by and watch people engage in wholesale warfare against human beings? The parallels are extremely striking.

Finally, I think it really shows us this: Until we root out these anti-human, anti-humanity tendencies in any government, they will not only persist [but] they will intensify. And I think we’ve reached a point now where we have to do something about this. And Du Bois and Robeson show us what happens when you pick people over that kind of fascism.

Hagopian: Thank you. I mean, they were like the OG Black identity extremists.

Carr: Exactly. But Robeson was born in 1898, so when they really started coming to consciousness they’re in their 30s. Paul Robeson first starts talking about “I had no choice but to make my choice as an artist. Some people would say, “Well, that was then. Give young people time to grow; we all need time to grow.” But Paul Robeson’s like 38, 39 years old when he first makes that statement about the role of the artist, so I think one thing our young people don’t necessarily do enough of — and you’ve got some master teachers in this room, and I think a lot of people do it but there may be a few who don’t do it as much, and I’ve been guilty of this — is help our young people understand the ages at which these folks were when they did what they did. Paul became a Broadway star in his 20s, he’s like 24, 25 years old and he’s a movie star, so don’t think about him and then look at movie stars now and say, “Well that was different. He was a lot older now.” He was actually younger than them!

Hagopian: Yeah, I appreciate that emphasis on how much young people have changed the world, because you’ve got to look at the Black Panther Party being founded by teenagers and like incredibly young folks building it. King wasn’t all that old himself. A lot of these leaders were pretty young when they got started and making that visible for our youth, I like that lesson [is] excellent. I want to continue in this vein of looking at the connections between Robeson’s life and lessons we can apply today, because I think with white supremacy on the rise today, what lessons can we take from Robeson’s struggles against fascism, for workers rights? He was unapologetically for Black liberation and for socialism, for revolution in this country.

Deborah has a song queued up, so maybe we could play this song before you answer to show you Paul Robeson’s connection with the labor movement and the socialist movement. Joe Hill was a hero of his from the IWW, the International Workers of the World, and he sings this song beautifully, this tribute to Joe Hill. [music plays]

I don’t have the same baritone, but I sing that to my sons. But I changed the last verse from Seattle all the way to Maine. But talk about his labor radicalism and socialism.

Carr: Absolutely. It’s interesting, this is the book by Charles Wright, all Detroiters know the Charles Wright Museum is one of the oldest American museums in the country. It’s called Robeson: Labor’s Forgotten Champion, and of course the folks in Detroit, and their pictures, here Paul Robeson with Coleman Young. When he was a state senator, he worked with the National Negro Labor Council. Remember, Robeson was at the height of his popularity in the 1940s, when A. Philip Randolph and them threatened to shut Washington down if they didn’t desegregate these jobs in the military. And Executive Order 803, of course, we know comes out of that: World War II. Robeson’s in that fight, that fair employment practices committee that comes out of that. Anna Hedgeman, who helps lead that fight. He’s in the middle of that labor fight and he worked particularly with the Congress of Industrial Organizations. He’s fighting against racism in the unions but at the same time he’s also saying we have working class solidarity that’s global.

The films of which he was most proud — and we know Robeson stopped his film career when he said, “I can’t really play the roles I want to play” — one of them of course is The Proud Valley, where he is in solidarity with the Welsh miners. That’s what endears them to him and him to them, but his notion of global solidarity movements, built in the trade union movements, is really at the core of his work. It’s funny because Dr. Wright, who was a medical doctor who started this museum in his house, he’s got a chapter in there called “Robeson and the ‘Song Joe Hill’.” He’s talking about how this notion of global solidarity doesn’t have race at the foundation of its logic. In other words, Robeson doesn’t care what color you are.

But, I’ll end with this. He is absolutely an African. In other words, he’s a pan-Africanist, he’s anti-colonial, but he believes that it’s almost like he’s a cultural internationalist and an integrationist at the same time. It’s the best example that says everybody has something to give to the human understanding, but there’s a commonality underneath which is one of the reasons he started studying all those languages. He says, “I’m noticing this: The similarities between African languages and the way we speak in the United States as African people, but I’m also seeing these similarities in these European languages and then some of the Asian languages. Underneath the languages is commonality.” I think his attitude toward labor, his attitude toward the working class, his statements consistently about the fact that it is labor which allows us to have these societies that people are exploiting the poor with, he says that is a solidarity that must be the foundation of our modern societies. He was thoroughly committed to the labor movement.

Hagopian: That’s so beautiful, just the way he was able to weave together the struggle for Black liberation with a common struggle for all humanity. And a working class movement is one lesson I hope we can recover, not only to teach about in our classrooms but also to organize ourselves in our unions, in our team and our educator unions and beyond. That’s the next stage.

But, in response to that, I want to say that I think that in many ways the politics of people like Paul Robeson being marginalized by the far right, the McCarthy-like attacks, are very visible but I think also he was marginalized by liberals, by other people in the civil rights struggles, and I think today we also have a problem where liberals and Democrats discredit radical organizers. We’re seeing a struggle inside the Democratic Party today, I think, that highlights some of that. So, I wonder if you could comment on that?

Carr: Very quickly, I think I’m probably not the only one in our room tonight who chuckled a little bit when president-elect Biden accepted the nomination and opened his speech by quoting Ella Baker. How far are you going to go with Ella Baker, who of course was a great comrade along with Claudia Jones and the Robesons. You don’t really want that smoke. It’s interesting, you see somebody like John Lewis, for example, a new ancestor who made a point to meet Paul Robeson because Robeson, of course, had finally got his passport back in 1958 and they traveled around and came back. John Lewis said, “I want to meet, please. Thank you for everything you’ve done.” But people see he’s not connected, that same John Lewis, along with Jim Clyburn and some of the folks who are involved in SNCC from the beginning. Here we are in 2020, and here’s Congressman Clyburn, a deep comrade of Congressman Lewis and a man who traces back to what was going on around Orangeburg and South Carolina State, with South Carolina State saying, “Don’t be talking about defunding the police,” This is the danger.

Finally, what Paul Robeson represents, what Essie Robeson represents, is the fact that when you have a platform — young people now, they talk about platforms — when you have a platform like that you can inspire people by the choices you make. Which is why he writes in Here I Stand, I had no alternative.” He says you can inspire people to make different life choices. That is extremely unsettling to the political apparatus that is built on keeping those people powerless. Then the liberals — Black white, or otherwise — have a decision to make, because if you don’t think we can all win, you think you’re doing the best deal you can get, but it starts with you don’t think we can win, do you? So, I don’t even look at it as are y’all sellouts, no. You don’t think people can win, so you think you’re actually doing us a favor.

Robeson lived his life in a way to show you don’t have to compromise. I put a lot on his father, a lot of that on his family, but when you don’t compromise you threaten not only the structure but those who think you have to compromise. And by compromise I mean you have to accept something less than everybody should have — somewhere to sleep, everybody should have the dignity of labor, everyone should be able to have health care and education. If you don’t think that’s true, you just start cutting deals, and I think that’s where the liberals are.

Hagopian: It’s incredible. I think what you said about how someone with the platform really scares the establishment, but at the same time Paul Robeson knew that the change wasn’t going to come from him alone, or a collection of people with the platform, but by the masses of people. But I see an echo today with Colin Kaepernick using his platform. That terrified the establishment, that this religion of football on Sunday that was a shrine to American patriotism could get upset and could become a platform for radicalism, as well. I see how Robeson brought radical ideas to the mainstream in a similar way.

Carr: We see what they did, to Kap. I haven’t seen a downed knee in football since. But imagine not even Kaepernick, but in his time Robeson at Rutgers is a two-time all-American and plays pro football on the weekends. When he was going to law school, he beats Jim Thorpe’s team. That’s a whole other conversation about who Jim Thorpe is. This guy is the baddest athlete in the country and the baddest actor in the world and one of the top two or three recording artists. Put Lebron James with Drake, you know what’s there? In fact, I’m gonna stop singing for two years, and all he said was, “No more pretty songs.” Imagine the biggest name coming up saying, “No more pretty hip-hop. No more.” A guy that’s too big to cancel. You can’t cancel him; the only thing you can do is take his passport. Why? Because if you want to beef with him, he’s on a plane. Next thing you know a mountain was named for him in the Soviet Union, now he’s in China, now he’s in England. Take the guy’s passport and they still couldn’t break him.

Hagopian: Right. Another level, not just Kaepernick but mixed with Lebron and Drake. I love it, no question. You said that’s why they have to take his passport. It’s on another level. There are a couple more questions but we’re coming to the time to launch our small groups here.

There’s a lot in the UK to learn about Paul Robeson. Maybe you want to say a word about his relationship to the UK?

Carr: Of course. It’s interesting. Robeson was 32 years old when he got that role and we know he was born in 1898 in Princeton. He grows up in Somerville, goes to Rutgers on scholarship, Phi Beta Kappa there, goes to Columbia Law School, [and] gets married to Essie. Now, Essie is like, “Man, you need to maybe look at this stage stuff,” so he starts in the Black theater, then he comes over and gets on Broadway and he does Shuffle Along, things like that. Now he’s going to jump the pond in 1930 and go play Othello, which is still the longest running engagement of Othello in England. Now he’s really bigger than ever. And while he’s there, he and Essie — which is what she’s writing, African Journey — they start dealing with the Africans there, meeting the African students. He starts making movies, he films Sanders of the River, he’s not quite satisfied because they mess him up. He thinks it’s one thing [but] it’s going to be another thing. He then makes another movie, Song of Freedom. He’s meeting Jomo Kenyatta [and others]. A lot of these young students are going to end up leading their countries to liberation and liberation struggles in Africa.

This is the beauty of the technology: you can go into London archives. That’s where Paul Robeson is studying the languages, that’s where Essie is digging around in the archives, that’s where the West African Student Union basically makes them adopted continental Africans, which paves the way when Essie ends up going to the continent. All that stuff’s in the London archives. I mean, they live over there for over a decade. They bring Essie’s mother over with Paul Jr., and then they come back to the United States and so then, of course, after his passport is restored in 1957, 1958, then he comes back for another engagement.

Hagopian: I see there’s a couple questions in the chat about labor solidarity and Reparations and I think it would be interesting to talk about. I’ve heard people argue that if you’re fighting for Reparations that can go against labor solidarity because white workers won’t like it and it’s a divisive issue that could divide the working class. I wonder if you could respond to that and maybe what Paul Robeson might think?

Carr: Well, I think that that’s actually possible if we take a narrow view of Reparations. There’s a dimension of Reparations that are cultural, that are cultural spiritual, and that is the harm that was committed against people of African descent here in the United States, for example. Of course, we can’t underscore enough the fact that there are numerous people that have been damaged as groups, Native Americans of course included. But if we’re talking about a solidarity movement that accrues to the benefit of everyone, then we’re talking about something that is going to ultimately benefit us all. So the idea that everyone has health care, everyone has education, that’s a huge thing to build solidarity around.

Now, that still doesn’t address that psychic and cultural piece, which is why Katherine Franke, in her book Repair, for example, talks about the fact that there should be a Truth and Reconciliation Commission in the United States of America. Go beyond apologies. If you look at H.R.40, you were talking about how we address the specific harm against people of African descent. But I think, finally, somebody like Paul Robeson or Eslanda Robeson would never narrow that struggle to the four borders of the United States. It would be part of a global solidarity movement, a global Reparations movement.

Which is why we see, for example in the 1940s, Robeson, Alphaeus Hunton, and Dorothy Hunton start, along with their colleagues, the Council on African Affairs. They’re always talking about how the struggle here connects to struggles in other places and I think Reparations will be no different. It’s part of a global solidarity movement on behalf of people who have been harmed.

Hagopian: I appreciate that global perspective. Also, I appreciate what you said about how when one section of people are lifted up it helps everybody. I mean, we’ve got to learn that lesson right now, in the COVID era. We’re only as safe as the least insured among us. If people are getting sick and can’t access health care, then we’re all at risk. So, how do we look for the most injured in our society and lift them up? There’s a question that someone asked about how do we teach Paul Robeson to elementary school students?

Carr: That’s good. In fact, we were talking in our breakout room [about] a graphic biography of Paul Robeson, Ballad of an American: A Graphic Biography of Paul Robeson. It’s very interesting, the art and text by Sharon Rudahl, and it’s edited by Paul Buhle and Lawrence Ware. Folks know Paul Buhle probably because he is, among other things, the biographer of C. L. R. James. But this book doesn’t skimp on the scholarship. Everything we’re talking about now and a whole lot more is included in these pages, only about 120 pages. But it’s written in a kind of narrative style with the engagement that can be used as a point of departure for younger children. It’s not the first one.

In fact, if you want to talk about one for middle school students, there’s one called Paul Robeson for Beginners. This is a good one, as well. It’s a little bit more like seventh grade, eighth grade; a lot of narrative and photographs. But I love the graphic novel format not just for children but for any age. It’s a nice point of entry with a good bibliography.

I should say this, as well. In a lot of ways, Robeson teaches himself. I had a conversation about a month ago with some jazz musicians. We’re having a conversation and talking about creativity, and Robert Glasper, the jazz musician, said that as an infant he used to play Nat King Cole. He and his wife play Nat King Cole for their son, who is an infant. He said they would play it, he’d go to sleep, they’d turn it off, he’d wake up. Now he’s a teenager saying, “Start playing Paul Robeson.” Y’all, he didn’t want to turn that music off! My favorite [Paul Robeson song] was “Shortenin’ Bread.”

There’s a whole critique of Robeson’s music and theater, of his theater appearances in The Negro World. He’s not going unchallenged, but that voice, he could be singing out the telephone book children.

Hagopian: We have a little bit more time. In the chat there’s a lot of Robeson and King and communism.

Carr: Yes, I wanted to talk about that, please. We should just say very quickly that, of course, Essie did it first in 1953 [and] Paul followed in 1956, in his testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Paul said it’s none of your business whether I’m a member of the Communist Party or not. This is why we have these protections, these Constitutional protections. But Dr. King, very interestingly toward the end of his life, King . . . By the way, parenthetically of course, people often refer to Martin Duberman’s biography of Robeson and it’s got a lot of facts, but there’s so many different things, and a lot of Robeson’s people, [like] his son, Lawrence Brown, a lot of people wrote biographies. So, I would read them all if you have a chance.

But Malcolm X, at the funeral of Lorraine Hansberry, and Paul Jr. were in Harlem, and he said, “Can I meet you? Can I meet your father?” So they went up and said, “Well, maybe another time. He does admire you,” because this is 1965. and Malcolm’s assassinated before they can get together.

Here is the 75th birthday program for Paul Robeson. The great artist Charles White did the cover, and the committee included Harry Belafonte, Dizzy Gillespie, Alice Childress, and Pablo Neruda wrote a poem, a tribute to Paul Robeson, in this program. But the reason I bring it up is because the son of Elijah Muhammad, Warith Deen Muhammad, who’s now with the Nation of Islam, sends condolences when Paul Robeson passes away in 1976. Martin King isn’t one thing. He honors W. E. B. Du Bois after Dr. Du Bois had been ostracized. He sees Paul Robeson as a major figure in this solidarity movement. In fact, King’s unpopularity arguably is because he embraces another common world, a common global solidarity movement, not post-1965 as much as it probably was always there. Remember, he went to Ghana in 1957, he and Coretta Scott King, at the invitation of Kwame Nkrumah. The United States writes narratives and builds curriculums in ways to keep us thinking within the four corners of these borders. So, I wouldn’t trust anything coming out of conventional curriculum about anybody when you start talking about liberation movements because the reality doesn’t match up to the narratives. I mean, that’s one reason why y’all are working so hard.

Hagopian: That’s why we keep adding lesson plans as fast as we can to the website. We’ve got a couple good questions coming in, so I’ll give you a couple and we’ll see what we have time for. Turquoise asked about speaking about Paul Robeson and how they didn’t attend an HBCU. Then, somebody asked can you speak to the Black political elite turning their backs on Robeson?

Carr: The first one, very quickly. It’s interesting, Robeson got honorary degrees from HBCUs, two of them, Morehouse and Howard. In fact, Benjamin May’s remarks at the granting of the honorary degree is actually included in the 75th birthday program. But at the time, Paul Robeson was from Jersey and his principal at the time when he was in high school, the white principal didn’t tell him about this state exam they were going to take — if you scored near the top you could get free entry into Rutgers. Robeson was the top scoring high school student in the state of New Jersey and he went to Rutgers for free. Then he made the football team, became an all-American and Phi Beta Kappa.

His people are from Robertson, North Carolina, by the way. In fact, that’s where his father escaped enslavement and then joined the Union Army. So, I don’t think Robeson would not have gone to an HBCU, and he certainly understood the value of them. He had degrees from a couple of them, honorary ones. Essie, interestingly enough, Frances Cardozo, her grandfather ends up being the superintendent of this colored school in D.C. He’s a very important figure and when you look at Paul’s cousin, as I said, Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander was from Philly. Folks at the Robeson house know Sadie, her family sends her to Washington to go to arguably I don’t know maybe Howard was better. It’s hard to say. The M Street School, which was the best high school for Black people in the country. So there is a Black institutional theme on both sides of the Robeson family.

Now, the second question was about the Black political elite turning their back on Robeson. It seems like it’s fairly straightforward. You’re talking about a situation where the Black elite, in a Jim Crow American apartheid system, are negotiating with the white power structure, with the white elite, for access. Remember Paul Robeson is a lawyer technically, even though he really didn’t ever practice, but he doesn’t get involved in the legal struggle in that same way. He does lobby. They do anti-lynching, they try to get an anti-lynching bill passed in the 1940s, but that tiny Black elite which embraces Robeson — remember, Paul Robeson is the red carpet. I mean, he gets the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP, he’s beloved by these folks. But when Robeson jumps the shark for them, meaning expands that working class solidarity internationally, the United States is entering the Cold War and they come to this Black elite and said, “Look, what side are you going to pick, because we’ll lace you with this communist tag and all y’all will be in jail.”

So at that point, the NAACP, particularly Walter White and them, didn’t just throw Robeson overboard, they threw Du Bois overboard. The NAACP fired him, and he’s in his seventies in 1945. “You’ve got to go.” I was like what are you doing? Not to say that we’ve seen this show before, we’ve seen the Black elite tell the rest of the Black folk [to be] moderate, slow down, “there’s another way to do this.”

So this conversation in 2020 has its antecedents in the 1950s and 1960s, all the way forward. I stopped short of calling people sellouts because we realized that somewhere along the way we’d been trained to think — some of us and our children are often exposed to this — that individual success translates into success for the group. Robeson writes about this and Here I Stand, “my success means nothing if we haven’t moved together as a group.” When somebody like that says it, well, you’ve got to distance yourself from them because people actually listen to Paul Robeson. They’re not listening to him because he’s a politician, they’re listening to him because his records are in their house, because they saw his movies.

I should mention this, as well. When we think about Paul Robeson as a movie star in the 1920s people talk about The Emperor Jones. But his first movie in 1924. It was with the Black filmmaker Oscar Micheaux, Body and Soul. If you want to see somebody play a kind of schizophrenic good, bad at the same time, watch Paul Robeson in Oscar Micheaux’s Body and Soul.

Black folk love Paul Robeson because he enters their public consciences not as a political figure but as a cultural icon. So if you can’t just strictly get rid of him, you just stop speaking his name. And a lot of the disappearance of Paul Robeson had to do with the fact that he was extremely effective, so you got to get rid of him.

Hagopian: Wow, so many lessons came through today. Greg, your spirit just showed through the screen today and lit me up, so I really appreciate you. It’s just so great to be with everybody here today. Please go teach somebody about Paul Robeson after this. And check out the Robeson House.

Carr: Jesse, I want to thank you, man. I should mention one other thing. This is a great book by Jeffrey Stewart he edited called Paul Robeson: Artist and Citizen, an excellent resource.

Hagopian: Greg, your stacks of books are also an inspiration to me because I’ve run out of bookshelf room, too, and I’ve felt like, “Well I guess I should stop getting books at this point.” But you’ve let me know I can keep ordering. I’ll be okay. Thank you for that. So, we’re going to have to end this session, y’all. Thanks everybody for being here. I hope everyone has a wonderful evening and stays in the struggle.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Resources

|

Books and ArticlesEslanda: The Large and Unconventional Life of Mrs. Paul Robeson by Barbara Ransby Ballad of an American: A Graphic Biography of Paul Robeson by Sharon Rudahl, edited by Paul Buhle and Lawrence Ware Paul Robeson: The Artist as Revolutionary by Gerald Horne “Forge Negro-Labor Unity for Peace and Jobs” a pamphlet of a speech delivered by Paul Robeson “Freedomways Issue from 1971,” a Robeson tribute |

|

|

|

Films |

|

|

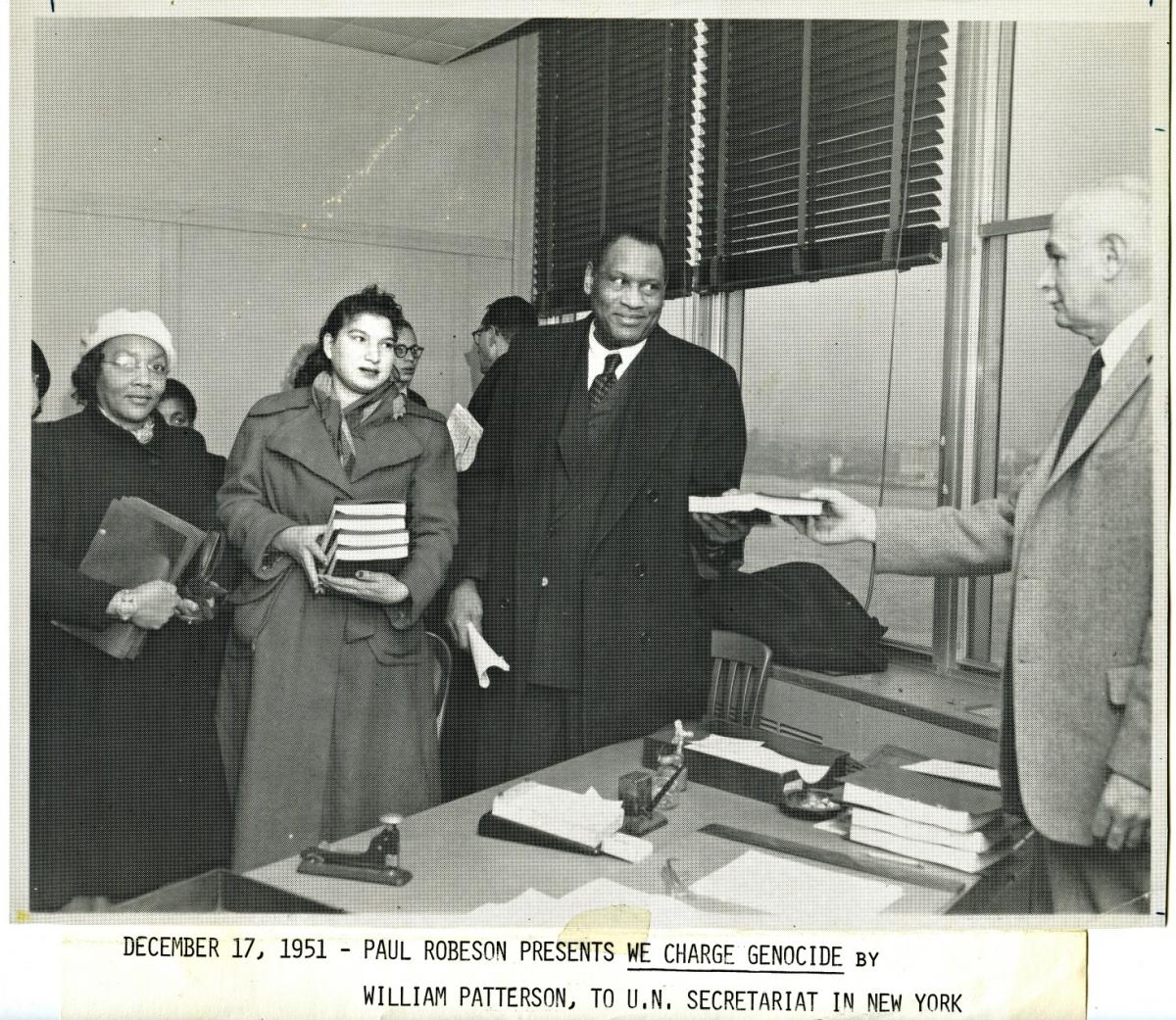

This Day in HistoryApril 9, 1898: Paul Robeson Born Oct. 14, 1916: Paul Robeson Excluded from Rutgers Football Team Sept. 4, 1949: Concert in Peekskill Attacked Dec. 17, 1951: “We Charge Genocide” Petition Submitted to United Nations |

Paul Robeson: On colonialism, African American rights

Watch on YouTube

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was learned

Responses to the question: What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today and what may you do with what you learned?

I learned again of the multi-faceted greatness of one of the 20th-century giants! I will continue to evolve my knowledge of this remarkable human being.

All of the information was so enriching! I’ll try to integrate him into the role of athletes beyond athletics role with social justice. I will be using your platform to step up my game.

It’s a problem that the curriculum is too white-washed to truly help black and brown students in the classroom. I am in the process of changing the curriculum at the school I attend. (I am a sophomore in high school.)

Paul Robeson believed we can win, and that we don’t have to compromise on basic human rights! Believe we can win and fight cynicism.

Not surprisingly, I must say that Paul Robeson was largely absent from most history textbooks in my upbringing. I definitely appreciated this webinar and I’m eager to do some reading about Paul Robeson.

The multiple impacts of Paul and Essie Robeson. This was nearly my first exploration of these incredible ancestors. I will be reading more about Paul Robeson, and looking for ways to include their voices in the elementary classrooms.

I’m going to use what I learned tonight to motivate me to learn more about Robeson and then share my learning with my network, including current teachers.

I learned so much I didn’t know about the brilliance of Robeson and his wife! It will influence how I think about librarianship and teaching youth about them.

The class has me thinking beyond our borders in terms of solidarity & healing. I am a DEIB facilitator, it is always good to have more stories about those that came before.

Robeson’s role as a leader despite his “cancellation” by far-right McCarthyism. I’m currently doing a unit on unsung heroes, so this will be used soon in class.

Paul Robeson’s multifaceted identities and how we can teach students that people do not need to be one “thing” to be known. I am in the process of applying to grad school for social studies education and I am excited to use what I learned today in my future classroom and lesson plans.

Great to see so many educators keen to teach him and connect with people from all over.

I learned a lot about Paul Robeson; had heard of him but didn’t know a lot about him. I’m always looking for specific people/stories to share with students. I can see including Robeson in both my Cold War and Civil Rights studies.

I learned the most about the work of Eslanda Robeson. I’m going to incorporate her into my art and my class.

That nothing defined him but himself. I’m going to make sure I talk about him and encourage more research.

The background and role of Essie Robeson. It reinforces my teaching of labor history.

His unshaken solidarity with the oppressed. I will be teaching about Paul Robeson to my drama students.

Just how popular Robeson was and how/why the Black political elite turned their backs on him when his politics became too radical. I am not a teacher but I will get one of the books that were talked about on the call.

I don’t know where to begin — everything. The “we charge genocide” petition, Paul Robeson for beginners, this is what you’re up against and this is what we can transform. I need to build lessons with other abolitionist teachers, invite more people to these sessions, and stay in the struggle.

Dr. Carr’s wealth of knowledge is always the most important. I appreciated his zest and encouragement for seeking the truth for ourselves when it comes to liberation. I look forward to reading and sharing resources with parents and students.

Everything was amazing but I loved the clip at the beginning when Robeson speaks of the greatness of Africans. I loved that this exceptional person speaks of the commonness of African greatness. Continue to learn and teach.

I learned how to incorporate Robeson into the classroom in a way that connects to humanity. I will add this information into my American Studies 101 Genealogy of Black Struggle unit at Purdue.

I’m intrigued by the ways the Black elites moved away from him and his work as soon as the fear of communism gripped the country and the Red Scare provided an opportunity to the Civil Rights Movement to make legislative gains.

Dr. Carr made us feel as if we were walking down the street with Paul Robeson. I need to include this approach in my next presentation.

Understanding the connections of his impact in this country and across the world in all aspects of society. I plan on developing lesson plans for each grade level in the 3-8th grade school I work at to honor and celebrate him. Additionally incorporate him into the curriculum.

The connection with international labor movements. Keep looking for stories of untold influencers and be suspicious every time I don’t find the untold.

Brilliant history and insights of the life of Paul Robeson and Essie Robeson. Looking forward to exploring the resources mentioned tonight. Our breakout group discussed a question that surfaced with this thought. Q:”How do we operationalize Robeson’s life ideas?” Answers varied but included action days, mutual aid, etc.

Just the closeness of this history, the reality of Paul Robeson’s existence, his triumphant life, and that the struggle he fought is still to be fought today. It makes the reality of the fight even more real for me in my life today.

I learned about the disappearance of the most famous American in the world.

I appreciated the correlations between 1940s liberation movements and today’s protest for individual rights.

If you don’t think you can win, you shouldn’t organize. I am retired, I will tell my former colleagues how to access these ideas. Paul Robeson was a renaissance man. Important international figure. Sad that nothing is said in traditional schools.

That we need to identify the age of the historical figure at the time they perform the act. I am going to incorporate some pieces about Paul Robeson into my next unit in Ethnic Studies/Sociology.

His unshaken solidarity with the oppressed. I will be teaching about Paul Robeson to my drama students.

I am taking away so much: the resources, connecting with fellow educators, all the knowledge dropped by Dr. Carr.

All of the information was so enriching! I’ll try to integrate him into the role of athletes beyond athletics role with social justice.

Paul Robeson’s multifaceted identities and how we can teach students that people do not need to be one “thing” to be known.

The format

I liked it! I could listen Dr. Carr speak ALL day. Wow. Please bring him back next year!

Loved the presenters! The chat was lively, sometimes overwhelming. Enjoyed the breakout rooms.

Everything was extremely well done. Dr. Carr was animated, informative, humorous, etc.

I think the format was great. It left the participants hungry for more and I think that is a good thing.

This format WAS DOPE!!! I have been to so many ZOOM meetings but never to one that encouraged participants to connect. That was so amazing and lovely.

I loved the breakout groups and Dr. Carr and Jesse’s easy story-telling filled dialogue was engaging and delightful. The breakout groups still seemed short (there were 7 people in mine) but it was still a good conversation for the time we had.

The breadth of understanding of the speaker was huge. The connections drawn between global solidarity, economics, reparations, meaning a change to a system that works for all plus attention to the particular harm done to people, the flow.

I thought the interview format worked well. Breakout group size was good.

I liked the organic structure where everyone contributed to the conversation while observing other participants’ body language and their responses.

I personally loved the banter. It was 4:00 for me — I was screened out and a little brain dead. It was nice to just absorb and take notes instead of having to perform for my students online.

Loved the format — the breakout session got us talking to each other, but the plenary was excellent.

Additional comments

This was an absolutely amazing class! Thank you for organizing this.

Thank you

Was in a breakout group with Bill B, codirector of Zinn. That was super. Jesse is a star. And Deborah. HUGE FAN of Zinn. Dr. Carr was on fire tonight!

Thank you for providing this amazing guest speaker! I will look for more of these zoom sessions in the future.

Great event. Cannot wait for the next one. Learning is a lifelong experience. Always glad to be a student of the universe.

I would definitely attend another class and I will definitely donate to keep this work growing!

Thank you so much. It was wonderful to be here with Dr. Carr, Jesse, and all of you. Grateful to be a part of this.

Loved Greg Carr’s energy — proof that Zoom doesn’t squelch anything! I have to take a sabbatical to do all this reading!

Entirely worthwhile. Great work, Deborah and Teaching for Change and Rethinking Schools and Zinn Ed.

Looking forward to the resources so I can add to my book towers

Thank you Dr. Carr for being so generous with your immense intellect. I have learned from you for decades. I look forward to continuing to learn from you for decades.

Thank you so much for organizing this program! Much needed, appreciated, and well worth the time.

Always a great opportunity to expand my knowledge and that of my students/colleagues.

Thanks to Dr. Carr, all facilitators, and participants for their insightful contributions to the conversation.

Great to see so many educators keen to teach him and to connect with people from all over.

For me, this serves as a starting point to an exciting educational journey.

Presenters

Dr. Greg Carr is Associate Professor of Africana Studies, chair of the Department of Afro-American Studies at Howard University, and Adjunct Faculty at the Howard School of Law. Carr is co-founder of the Philadelphia Freedom Schools Movement and an advisor for the Zinn Education Project’s Teach Reconstruction campaign.

Jesse Hagopian is a teacher, author, activist, and a Zinn Education Project writer and organizer. He previously taught Ethnic Studies and was the co-advisor to the Black Student Union at Garfield High School in Seattle. Hagopian is an editor for Rethinking Schools, the co-editor of Teaching for Black Lives, and editor of More Than a Score: The New Uprising Against High-Stakes Testing.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn