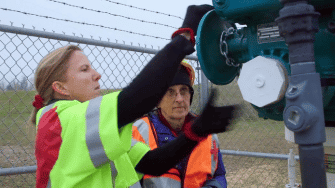

Photo from film Necessity by Morgan Robinson.

Ursula Wolfe-Rocca built this lesson around the documentary film, Necessity: Oil, Water, and Climate Resistance, which details the story of multiple cohorts of climate activists: Indigenous leaders in the Climate Justice Movement, valve turners using civil disobedience to stop the flow of oil, and the legal team that uses the “necessity defense” in the courts. Through the activities within, students engage with excerpts from the film and a mixer role play based on the real-life subjects of the film. Here is an excerpt from the introduction to Wolfe-Rocca’s lesson.

Ursula Wolfe-Rocca built this lesson around the documentary film, Necessity: Oil, Water, and Climate Resistance, which details the story of multiple cohorts of climate activists: Indigenous leaders in the Climate Justice Movement, valve turners using civil disobedience to stop the flow of oil, and the legal team that uses the “necessity defense” in the courts. Through the activities within, students engage with excerpts from the film and a mixer role play based on the real-life subjects of the film. Here is an excerpt from the introduction to Wolfe-Rocca’s lesson.

Ask a high school student to list examples of civil disobedience and they are likely to include Rosa Parks. The ubiquity of the transcendentalism unit in the high school English curriculum means a few might throw in Thoreau’s refusal to pay taxes to support war. Maybe one or two kids will have heard of the sit-ins. But in my 20 years of teaching, students almost always refer to civil disobedience as a relic of the past, never as alive in their own time. This is not students’ fault; page through any mainstream textbook and you will see civil disobedience frozen in sepia-toned images of the past, a distortion that misleads students into thinking that this political strategy is as dead as the dinosaurs. It’s a falsehood this lesson seeks to correct.

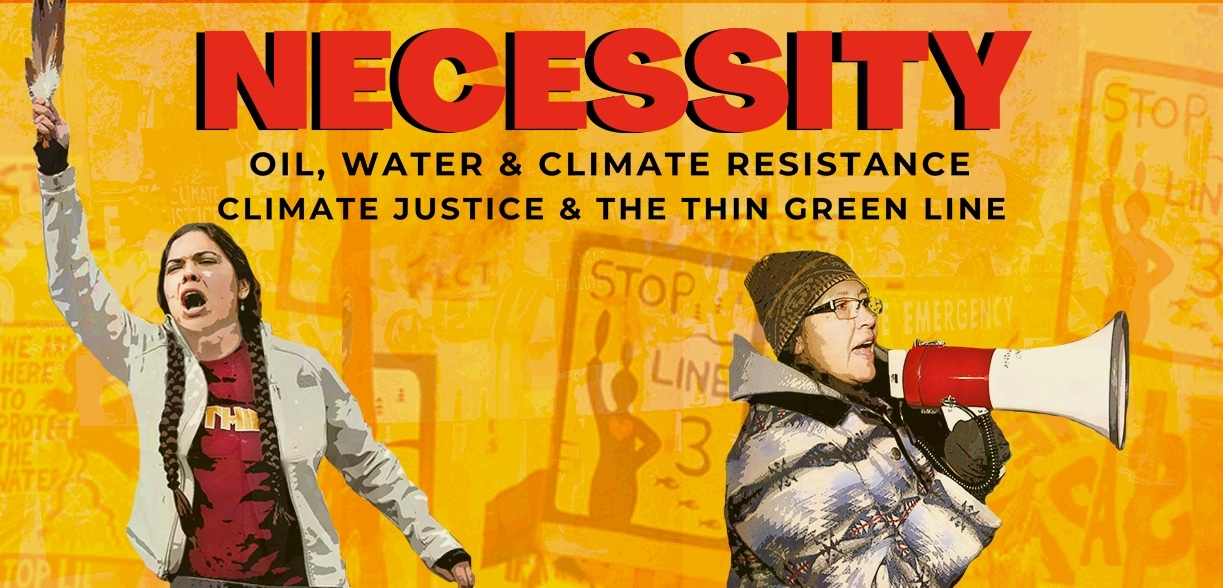

Photo from film Necessity by Morgan Robinson.

In October 2016, five middle-aged white activists from Washington and Oregon became “valve turners,” coordinating the (illegal) manual closing of the emergency shutoff valves on Canadian tar sands pipelines across four states: Washington, Montana, North Dakota, and Minnesota. Their actions were a response to the call by Indigenous activists for “International Days of Prayer and Action for Standing Rock.” They explained:

We have tried every avenue by which engaged citizens might advance such concerns — in this case, ecological — in public policy, and nothing has worked. There is no plausible means or mechanism by which the extraction and burning of coal and tar sands oil from existing mines and fields can be halted on the timeline now required by any ordinary, legal means.

Arrested and charged with trespassing, sabotage, burglary, criminal mischief, and other “critical energy infrastructure” crimes, all the defendants mobilized a “necessity defense,” a legal approach that does not deny the defendant’s criminal action, but argues that it was carried out in order to prevent a greater harm — in this case, the continued extraction and burning of fossil fuels that is warming the climate and wreaking catastrophic damage to all forms of life.

Water protector Debra Topping, Fond du Lac Ojibwe, from film Necessity. By Morgan Robinson

While the mainstream media paid little attention to these dramatic acts of civil disobedience and the trials that followed, filmmakers Jan Haaken and Samantha Praus created an hourlong documentary about the valve turners’ actions to support the ongoing and Indigenous-led movement against Enbridge’s Line 3 in Minnesota. Necessity: Oil, Water, and Climate Resistance is a film we should introduce to our students. It weaves together many strands: the pipeline’s particular threat to the Indigenous people through whose land it runs; pipelines’ universal threat as conveyors of the fossil fuels that are scorching the Earth; and the rich array of creative activism — exercised by differently positioned groups and individuals — needed to sustain a successful climate justice movement.

This lesson is designed to accompany the film, which is available to stream on most platforms. The mixer role play includes 19 characters from the film’s storyline — most of whom appear on camera and a few who do not. I wanted the activity to build anticipation for students’ viewing of the film; the roles explore the motivations and actions of each of the activists, but do not reveal the outcomes of the trials or whether any of the defendants succeed in their mobilization of the necessity defense. I also hoped students would feel a jolt of excitement each time they saw someone onscreen that they had already “met” in our class activity, and have a bit more of a stake in tracking their stories in the film.

This lesson is designed to accompany the film, which is available to stream on most platforms. The mixer role play includes 19 characters from the film’s storyline — most of whom appear on camera and a few who do not. I wanted the activity to build anticipation for students’ viewing of the film; the roles explore the motivations and actions of each of the activists, but do not reveal the outcomes of the trials or whether any of the defendants succeed in their mobilization of the necessity defense. I also hoped students would feel a jolt of excitement each time they saw someone onscreen that they had already “met” in our class activity, and have a bit more of a stake in tracking their stories in the film.

I want my students to have the examples of civil disobedience revealed by Necessity because it is going to take all of us doing what is necessary to secure a livable planet. Our classrooms can join that effort, whether in-person or online, by sharing the stories of justice seekers who choose action over apathy, “making a way out of no way,” and providing hopeful models on which our students might build a possible — and necessary — future.

Use the “Download to Read in Full” button below to access the lesson.

Read an article by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca on teaching the lesson in Rethinking Schools, Protesting Pipelines: Teaching the Indigenous-Led Movement Against Fossil Fuel Infrastructure.

The individual roles in this mixer include:

- Tara Houska, an Ojibwe citizen of Couchiching First Nation, living in what is today Minnesota

- Anthony Ingraffea, a professor of engineering at Cornell University

- Debra Topping, an Ojibwe woman living on the Fond du Lac reservation in Minnesota

- Ernesto Burbank, a Water Protector, a tattoo artist, and a citizen of the Navajo (Diné) Nation

- Michael Niemi, who linked arms with a fellow Water Protector, Ernesto Burbank, and chained themselves to the security gate at a Wells Fargo bank in Duluth, Minnesota, preventing the bank from opening

- Scot Bol, who placed a U-shaped bike lock around his neck and fastened himself to the security gate at a Wells Fargo bank in Duluth, Minnesota, preventing the bank from opening

- J. T. Haines, a lawyer who acted as a defense attorney for three protesters who chained themselves to the security gate at a Wells Fargo bank in Duluth, Minnesota

- Jennifer McEwen, a lawyer who acted as a defense attorney for three protesters who chained themselves to the security gate at a Wells Fargo bank in Duluth, Minnesota

- Bill Grant, deputy commissioner of the Minnesota Department of Commerce

- Winona LaDuke, executive director of the Indigenous environmental justice organization Honor the Earth

- Emily Johnston, poet and anti-pipeline activist

- Annette Klapstein, a retired attorney and anti-pipeline valve turner

- Benjamin Joldersma, who illegally gained access to a tar sands oil pipeline in the tiny town of Leonard, Minnesota, owned by the Canadian company Enbridge Energy, and shutting it down

- Vanessa Gray, who broke into a fenced-off valve area along Enbridge’s Line 9 pipeline near Sarnia, Ontario, and closed the valve’s manual wheel to stop the flow of oil

- Alice Cherry, a climate movement lawyer and founder of the Climate Defense Project (CDP)

- Kelsey Skaggs, executive director of the Climate Defense Project

- Dr. Bruce Snyder, a clinical professor of neurology and expert witness at a valve turner’s trial

- Dr. James Hansen, who has been arrested five times for my climate activism

- Lauren Regan, a movement lawyer and founder of the Civil Liberties Defense Center (CLDC)

Classroom Story

Among the many ZEP lessons that I incorporate into my curriculum, a powerful and relevant one that I adopted for distance learning this year was the role play for the film “Necessity: Oil, Water, and Climate Resistance.” I had not heard of the film and was so glad to have found it through the Zinn Education Project. It was perfect for our U.S. history course with an Ethnic Studies lens, through its various intersections of indigeniety, climate justice, advocacy, and more.

Living in the Pacific Northwest, many of my students were unaware of the controversies and dangers around oil pipelines, specifically Line 3 and the story told in this lesson. They made deep connections to the challenges of indigenous peoples protecting their sacred grounds and waterways, especially since we have local water issues as well and Alberta Tar Sands oil passing through our great state. Many of my white students also saw the action of the valve turners and attorneys as empowering and inspiring to the ways that we all can be advocates and protect our earth and native peoples. Thanks so much to Ursula Wolfe-Rocca, Zinn Education Project, and the role models for social justice protecting our waters and sacred grounds as taught through this lesson.

Share your story about teaching with Necessity or any of our climate justice lessons and we will send you three climate justice books — free!

This is awesome! I was curious about also using the documentary Powerlands (2022) to tie in the struggle globally for Indigenous movements fighting against similar issues.