On October 19, the first Teach the Black Freedom Struggle class of the fall featured a conversation between Charles M. Payne and Cierra Kaler-Jones.

The session, Organizing for Voting Rights: Lessons from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) addressed themes of our campaigns to Teach the Black Freedom Struggle and to teach about voting rights on this 150th anniversary year of the 15th Amendment and an election year.

During the class, Payne shared stories and analysis from the oral histories he collected on the grassroots, intergenerational organizing for voting rights in Mississippi. Our hope is that students can apply lessons from SNCC to challenge widespread voter suppression today.

In Teach Freedom: Education for Liberation in the African-American Tradition, Payne talks about the importance of sharing these lessons from history.

On the Sea Islands, where Septima Clark began her life’s work, when a respected person passed away, after the internment, custom called for children to step across the grave. The best parts of the spirits of the deceased were understood to pass into the children. As a nation, we have done a terrible job of passing our children over the graves and, given their already tenuous relationship to the rest of society, that failure often falls with greatest weight on African American and other children of color. That may be the best way to think of what education for liberation does at its best: It is a way to pass children over the graves of their ancestors, to give them a moral grounding in the past that will help them ask their own questions in the present and seek their own answers.

Here are just a few reflections from participants. (More reflections at the end of this page.)

I was unaware of the span of years prior to the ’40s in the deep south when voter registration and voting were accessible to Black people and poor whites.

What stuck with me was the explanation of the fallacy of waiting for a leader to move the movement forward — the idea that it was often the most vulnerable who did the heavy lifting in the resistance.

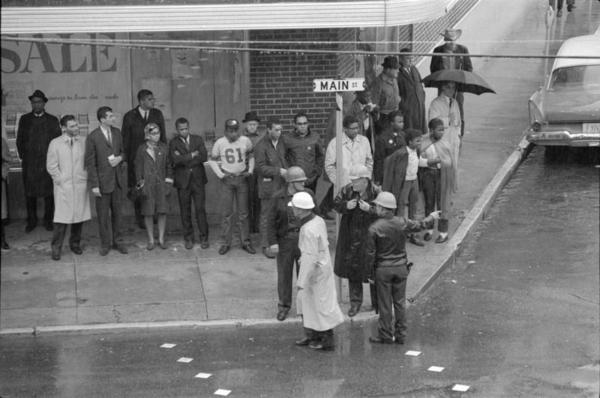

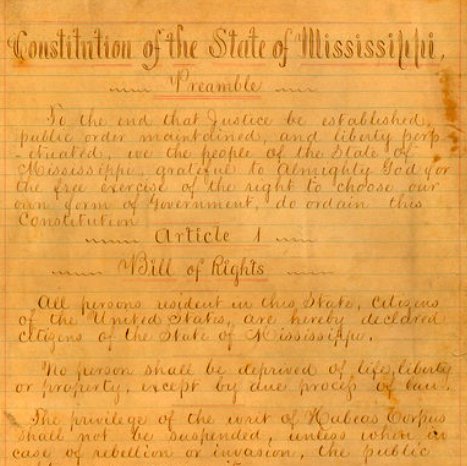

I hadn’t known that people’s addresses would be published in the newspaper for two weeks if they registered to vote!

“Truth-telling is a form of love.”

The breakout rooms always up the energy, the vulnerability, the connections, the humanity. Thank you.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

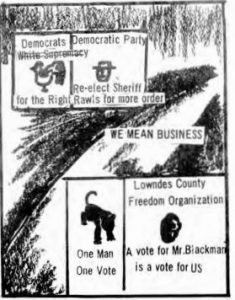

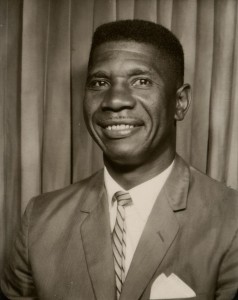

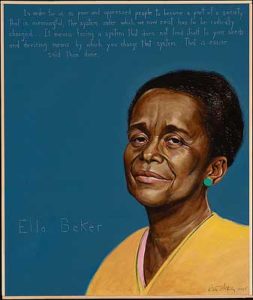

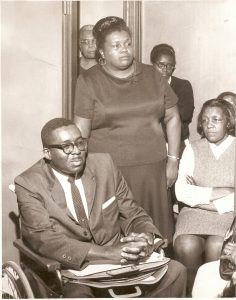

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion. Cierra Kaler-Jones: Hi everyone! It is so good to be back for our fall series of the Teach the Black Freedom Struggle. Welcome to everyone here on behalf of the Zinn Education Project for our session on Organizing for Voting Rights: Lessons from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee — SNCC. This is our first session in the fall series on the Black Freedom Struggle, and some of you are joining us for the first time, and some have participated in our spring series. It truly is a gift to be able to share this time together, and I thank you for being in virtual community with us. Before I begin my conversation with Dr. Charles Payne, we want to find out who is in the room and [then] I’ll go through our plans for our time together today. We are going to do a quick poll to find out how many teachers, librarians, teacher educators, historians, students, parents, caregivers, and others are in the room with us. Many of you are in multiple roles, but just pick your primary one. As we post the poll, I will introduce myself. My name is Cierra Kaler-Jones, she/her, and I am the Education Anew Fellow with Communities for Just Schools Fund and Teaching for Change. I’m also a PhD candidate at the University of Maryland, College Park, studying education. My work explores how Black girls use art space practices like movement, music, hair, as mechanisms for identity, development, and resistance. The Zinn Education Project is hosting this session today and offers free downloadable people’s history lessons — many that you all have used and many that I’ve used myself — for middle and high school classrooms from the Zinn Education Project website. We have a new campaign to Teach the Black Freedom Struggle and this online class that you all are a part of today is offered as part of that campaign. Alright, so let’s see the poll results. Okay, hopefully everyone can see them. We have in the room with us today 54% educators; we have 8% students, very exciting; 2% primary family members and caregivers; 8% community labor and organizers; 1% librarians, shout out to the librarians; 21% teacher educators; and 6% historians. We are so grateful to all of you for joining us today. Throughout this session, we want you to use the chat box to post your questions, your comments, resources, and ideas. We will read your questions and our guest speaker will try to respond after breakout groups. If you could put your questions in all caps, that’d be really helpful for us as we sift through all of the great resources and all of the knowledge that you will share in the breakout rooms. We will do our best to answer as many questions as we can in the time that we have together. We’ll do a short evaluation at the end. Please also continue this conversation on Twitter — we encourage you to share your learnings and your insights using the hashtag #TeachBlackFreedomStruggle. We are now ready to start our conversation. After about 25 minutes we’ll pause so that you can meet each other and talk in small groups to share your thoughts with one another. Without further ado, I am very honored and privileged to introduce Dr. Charles M. Payne. Charles M. Payne is the Henry Rutgers Distinguished Professor of African American Studies at Rutgers University-Newark and director of the Joseph Cornwall Center for Metropolitan Research. His research and teaching interests include urban education and school reform, social inequality, social change, and modern African American history, particularly the Black Freedom Struggle. He has written many books, and today we will focus our conversation on his book I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition in the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement. All right, so let’s do it. As we get started, Dr. Payne, I would love it if you could just give us an intro and just share what the voting rights struggle looked like in its early years in the Deep South. Charles Payne: Okay, well, first of all, thank you for that intro. I want to thank the entire [Zinn Education] Project. I liked the idea of doing something that is connected to Howard Zinn. He was a significant influence in my thinking and my growth. And a significant part of the movement, although I’m not sure very many people remember that. I just want to thank everyone for their interest. In ways that are too obvious to elaborate, the history that we’re talking about connects to the current moment in dramatic and sometimes frightening ways. So, I am very glad that so many people are taking this moment to look back to that moment, and to see what it can help us understand about this moment. Alright, so I’m going to take probably something like, maybe 10 minutes, if I can do it that way. I apologize in advance for talking very quickly. But I’ve got a lot of ground I want to cover, and I’m from New Jersey, so I can talk as fast as I want to — you can’t do anything about it. Ten minutes. I want to try to make four points about the early movement. One, I want to talk about how important the 1940s were. Two, I want to talk about how extraordinarily high the stakes were. So, one thing I just feel like hitting hard, it’s the price that people paid for change in the South, and who exactly paid that price. Obviously, a part of that question is going to be that women were the central point, which is still not sufficiently appreciated. And finally, I do want to say — and I may not put this in the first 10 minutes, we’ll come back to it later — I want to emphasize that SNCC was different. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was the Movement’s left wing. In some ways, along with CORE [the Congress of Racial Equality], it radicalized everyone else and pushed everyone else further and faster than they wanted to go — with respect to voting rights and doggone everything else. Anyway, the 1940s. If you take the number of African Americans registered to vote — which is not the same thing as the number of them actually voting — in the South, at the turn of the 20th century, 1900, it’s 3%; 1910, still 3%. For the best estimates, we had, I think, 1920, still 3%; 1940, still 3%; 1947, 12%; 1950, 20% of all African Americans in the Deep South were registered to vote. It’s very clear that, by that measure, the change, the break with the complete disempowerment of the past, comes during the 1940s. So, what’s happening in the 1940s? Well, two things we know: One, the Supreme Court decides in 1944 that Black people could not be excluded from primaries. And in the South, where you only had one party, the Democratic primary was in effect the election. So, by saying that the Democratic Party was a private entity and Blacks were not members, you effectively disenfranchised the whole race at one fell swoop. The Supreme Court and an NAACP suit ruled that to be illegal. At the same time, in 1945, ‘46, one million Black veterans came back from World War II, and they came back with an attitude — as did white veterans, by the way. That’s a parallel story. They came back with this notion that they were owed something, that they were entitled to have some of that democracy that they had been dying for. So, you had a movement across the South of what were often called progressive voter leagues — progressive was very popular. Even though they weren’t necessarily linked, veterans were active in a great many of them. And if I can successfully share my screen . . . okay. All right. Now, let’s look this way. I’ll be skipping around some. I’m not sure what I’m doing, so we’ll keep the confusion online. That young skinny man is Medgar Evers right there, in uniform. In 1946, [in the] first election after he comes home, he puts that uniform on, he gets his buddies, they all put their uniforms on, and they marched to the polls at Decatur, Mississippi. They get there and they find armed white men at the polls. They go home, they get their guns, they come back. Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed. Otherwise there would have been a shootout at the polls that day. But John Dittmer starts his book with his story. The symbolic importance of putting those uniforms on and demanding the rights that they had fought for. This next soldier from Cleveland, Mississippi is Amzie Moore, who was just a cathedral. He’s foundational to what was going to be happening in Mississippi. Amzie Moore said that being on a troop ship crossing the Mississippi to ship troops with across the Pacific, he learned that there was nothing special about white men. All the mystification that he had about white people growing up in the South, he lost that when he was so close to them. He lost that when he saw them in combat. So let’s say three, four years after he’s home, either ‘51 or ‘52, in Mound Bayou, Mississippi. If you can see my cursor, that’s Amzie Moore in the light colored suit in the center. He’s handing out information about how to register to vote. This is again in Mound Bayou, Mississippi, I think it’s actually 1952. And just look at the size of that crowd; this is a meeting of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership. But here is again another example of one of the veterans who came back to the South, and who came back intending to change the South. Across the 1940s and for the first couple years in the 1950s, registration numbers move up relatively steadily. By the standard of the Deep South, there’s not that much repression. People are able to do this without some of the extreme retaliation that’s going to become common soon. And what changes it up is in 1954, it’s Brown [v. Board of Education]. Brown makes the white South realize that they are being challenged. And all of a sudden, the white South mobilizes against every form of challenge. But perhaps it organized against the fight for the right to vote more than against anything else — that was perhaps the deepest fear. So what that meant, from 1954 throughout the rest of the 50s and the end of the 60s — but I’m going to concentrate for a minute, mostly, on the 1950s — what it meant to be an activist is that you ran a very strong chance of losing your job. I don’t know how to manipulate my screen well enough to do this, but this is to Black man trying to register. And the sign that I can’t read, I hope you can read, says something like, “You should know if you’re applying to register to vote that we’re going to publish your address in the newspaper for two weeks.” And then after that, two weeks after that, we might not or might not approve your request. What’s the purpose of publishing your address? So that every employer in town can know who has been trying to register to vote. And so that white terrorists can know where the people who are trying to register to vote live. If you had crops in the ground, you’re going to find no buyers. If you were sick, no doctor would see you. You could not get insurance. If you had a mortgage, the bank was going to try to foreclose. And then of course, we cannot overemphasize the sheer — not just the likelihood of violent retaliation — but the fact that the retaliation would not be against you as an activist, the retaliation would be against everybody connected to you. By trying to register to the vote, you put everyone around you in danger. And I want to illustrate that. Harriet and Harry T. Moore, NAACP organizers in Central Florida [in the] late 1940s, early 1950s. We still don’t know today whether they were killed because of the agitation against police brutality or because of their rapid pushing up of the number of Blacks trying to register to vote. It’s clearly an attack for one or the other but we don’t know [which]. Christmas Eve, 1951, home was bombed. Both of them were killed. Their daughter would have been killed except she was delayed slightly on the train coming home for the holidays. Their funeral was just a massive turnout of Black activists across Florida. Just turning out for the funerals, of course, is an act of defiance That also happened in Humphreys County, Belzoni, Mississippi to the Rev. George Lee in 1955, just before Emmett Till [was murdered], if I’m remembering the dates right. He had gotten something like 40 Black people to try to register to vote, to take the application. That’s an unheard of number in the Mississippi Delta at the time. The Chicago Defender starts off, “The Delta’s most militant minister Reverend George Lee had sworn despite threats that he would never withdraw his name from the town’s qualified voters list. . .” Then it goes on to say that he was shot one Saturday night at a drive-by as he was driving home. His friend and comrade Gus Courts said, “I will continue to try to get people to register to vote.” He led a march to the election office, and then when everyone else was intimidated and took their names off the voter application rolls, he refused to take his name off those rolls. He was shot — not killed, but he was shot — [and he] left Mississippi [and] lived out the rest of his life. The Medgar Evers story is not from the 50s, although I think he became secretary of the NAACP in ‘53 or ‘54, something like that. So everyone expected him to be killed in the 1950s. No one thought that you could keep that job and stay alive. But he was not killed until June 12 [1963]. He’s coming home after an NAACP rally. It wasn’t a great rally, he was probably not in the best mood. People hadn’t turned up. It was, again, a rally about getting out to vote. And he comes home and he’s getting out of his car in that driveway and a shot rings out and he’s killed by an assassin across the street. That’s Myrlie [Ever-Williams, civil rights activist and wife of Medgar Evers] and [Medgar’s] brother Charles at the casket. At the funeral procession Dick Gregory said, “It looked like we had enough people to march on god that day.” They were angry. It almost became a riot. It was very difficult for movement leaders. Medgar had a particular kind of respect in Mississippi and there was just enormously deep anger, deep abiding anger. In a little bit more time, Vernon and Ellie Dahmer in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, southern Mississippi. Dahmer illustrates a lot of the most important points, I think, about the people who sort of stepped out in this period of the Movement’s history. He was well to do, he was a dairy farmer, he had a grocery store. His wife was a school teacher. He had a sawmill and made a point to hire both Black and white workers in his sawmill. In 1953, he sued the sheriff of Forrest County because they wouldn’t accept registrations from Black people. But you’ve got to have a lot of nerves in 1953, Mississippi, to be suing the sheriff. It is particularly hilarious. He helped to start the NAACP youth chapter there, partly because the adults were too afraid to take part. Some remarkable young leaders came out of that youth chapter in the 1960s when the SNCC kids came. They fed them, they gave them walking around money. They used his vehicles to do their canvassing. He was solidly behind the movement. In 1965 the Voting Rights Act passes. He goes on the radio from his grocery store at the first election and tells people, “If you are afraid to go downtown and be seen paying your poll tax, come pay it at my store. If you don’t have the money to pay the poll tax, tell me that and I will pay the poll tax for you.” One night, after he had made that announcement, his home was attacked. The grocery was broken into. It’s not clear why; he and his wife for years had taken turns being up at night guarding the house. It’s just not clear why that night then they did not have a guard. They did not have a guard on the house. They were attacked by 14 members of the Ku Klux Klan. It later turned out, the 10 year old daughter was badly burned. They would all have been burned to death in that house had he not stood in the front of the house having a gun battle with the people who were attacking while his wife and daughter got out of the back. He was badly burned, his lungs were scorched, his face was disfigured. He continued, from his hospital bed, to broadcast about the need to vote — from his hospital bed — with “People who don’t vote are dead beats on the state.” He never left the hospital. “If you don’t vote, you don’t count,” that was one of the things he was famous for saying. So, the first point that I want to make is that, obviously, most college students studying American history will never hear any of those names. Medgar Evers, maybe, although most likely in a glancing way. What gets lost in the master narrative, I think, what gets lost in the traditional way of telling American history, is the fact that the greatest price for change was paid, in many cases, by some of the most vulnerable American citizens, some of the poorest citizens who had the least in the way that we normally normally measure things. If you look at any years, and it’s so dangerous,1950s, at least the first half of the 1960s — who are the people who stepped out? I mean, given all that was at stake, who are the people who took the risk? Who stepped out? I just want to make two points about that. One, they were very often land-owning Black people. The woman there is Winson Hudson, from Harmony, Mississippi. She owned about 105 acres, and that 105 acres was used to do everything you can to keep the movement going. She bailed people out of jail; she gave housing to people who were evicted because they tried to register to vote; she created safe space. This man that I skipped, another land-owning farmer, both of them are not only landowners, both Hartman Turnbow, here, and Mrs. Hudson were part of communities of landowners and people. All their neighbors would have also been land-owning Black farmers. They were among the staunchest. They were among the first to come into the movement [and] they were among the last to leave. Obviously, I think many of the folks on this call — I should say, the point about land-owning is probably best put by saying the people were most likely to stick their necks out where people had some degree of economic independence. So, land-owning is one example of that. Another would be being a barber, being a beautician, in which your income stream is not dependent on white people, or at least not directly dependent on white people. On the other side of that, if you were a teacher, white folks directly controlled your salary. So teachers were among those least likely to participate in the movement. In this period, preachers — even though much civil rights historiography celebrates the central role of the church, it’s much more complicated than that. The role that the church played in rural communities is not the role it played in urban communities. Even in urban communities through the early 1960s, the church was often as likely to be critical of the movement as to be supportive of it. We think about Birmingham as the church-based movement; by 1963, at the heart of that movement, less than 15% of the Black churches in Birmingham were participating. That’s why you had to get a children’s march, because the adults. . . But to go back, I just wanted to say economic independence is one of the things that predicts who takes a chance at the moment when things are most dangerous. But another is simply gender. And while on this call, I’m sure there are going to be some folks who have some opinions about it, we don’t have any broadly accepted explanation that I know for the fact that in the rural south, during the years of the greatest violent retaliation, women participated at a much higher rate than men in every form of movement participation — from joining organizations to showing up at mass meetings to going down to register to vote to join[ing] citizenship classes. It doesn’t matter what the form of it is, in the middle years, women are — depending on where and when you are — two, three, sometimes four times more likely to participate than men in those years. If you talk about old folk, the old fellas were out there — folk in their 60s and 70s. If you talk about young people, no different — teenagers, people in their 20s. But if you talk about folks with middle years — 30s to 50s or 60 — there is an enormous difference in who participates. So, I’ll just talk about some facts just to mention some famous and not so famous names. Mrs. [Fannie Lou] Hamer, that is a wonderful quote. “Sometimes it seems like to tell the truth today is to run the risk of being killed. But if I fall, I’ll fall five feet, four inches forward in the fight for freedom.I’m not backing off.” That is pure Mrs. Hamer, her running buddy, also from Hattiesburg, Mississippi, Victoria Gray Adams. This is the Atlantic City Convention in 1964. She was just a powerhouse in terms of her ability to influence the movement. Less well known, but one of the most respected people in the movement, period, was Annell Ponder, Mississippi director of citizenship education, trying to teach people what they had to know in order to pass the test to become a voter. June Johnson, in this picture she looks a little older than 16, [but] she was 16. She, Annell Ponder, and Mrs. Hamer were returning from one of Ms. Ponder’s classes on citizenship education when they were stopped because the bus they were riding in had too much yellow and it broke the law in the eyes of Winona, Mississippi. The cops took them into jail and spent something like two days just beating them on and off. Mrs. Hamer would never walk right again after that. She had a permanent limp; beaten within an inch of their lives. There was a myth at one time that women were more likely to participate because they were less likely to face violent reprisal. That’s just not true. It just does not add up. One of the most influential members of the early voter registration movement is the woman in the middle, seated here, Septima Clark, and her niece standing there, Bernice Robinson. There’s a movie coming out about Bernice sometime soon, sometime this fall. Septima Clark created the Citizenship Schools, which went across the south teaching people how to be citizens, how to register to vote. That often meant, as in this picture, we had to teach people how to write first, because so many southern states had passed literacy requirements before you could vote. They sent Black people to schools where you could not learn very much. So Septima Clark plays a powerful role in creating the local army of leaders who are going to be crucial across the south. Like Ella Baker. She had this enormous confidence in the capacity of ordinary people to play leadership roles. Ella Baker is the guiding spirit of SNCC, the source of much of what is intellectually distinct about SNCC. In 1960, when the sit-ins starts, she calls the meeting out of which SNCC grows. Central to her philosophy is that while all leadership types [are] unnecessary, certain kinds of leadership — top down, male driven, charismatic leadership — gets overplayed. It’s not that she would say it doesn’t have a role; there are times when you need exactly that. But that kind of leadership is stressed so much that we tend to not spend the time developing the leadership capacity of ordinary people. When she says, “I have always thought what is needed is the development of people who are interested not in being leaders as much as in developing leadership in others.” So, I think part of what we have to assume is that if SNCC is going into town with this notion of developing leadership in others, the untapped pool of leadership is going to be largely female. I think that is a part of why SNCC. But even within SNCC, the degree to which women became a part of the movement varied from place to place. Kaler-Jones: You bring up so many really powerful stories. How you have taken these master narratives and flipped them on their head. To think about the rich storytelling and the narratives and some of the folks that you’ve shared, like Septima Clark, Miss Ella Baker. I’ve introduced my students to them through some of the Zinn Education Project mixers and the role plays, and to see how they embody these women and take on these roles to feel so powerful in themselves and the rich history of organizing. You talk about the reminder that social history tends to ignore or forget the influence and the impact of ordinary people. And the tradition of Black activism really emphasizes the long term leadership of ordinary people. So, for the educators that are on the call, textbooks and the mainstream media often focus on the heroes and the heroines. What is the impact, if we continue to focus on those heroes and those heroines, in society and in our classroom? Payne: Yeah, it’s a complicated question. When I ask Black students what they get from these stories — as you say, from being introduced to these people — all students irrespective of race come away thinking, “Well, why didn’t I know about Ella Baker?” They find her thinking more complicated than, say, Martin Luther King’s thinking. More intriguing; there’s more to wrestle with it. Why didn’t I know about her? Why didn’t I know about Septima Clark? That’s crucial, because they’re asking the first question, right? If they lied to me about that, what else did they lie to me about? I’m going to argue the single most common remark I’ve heard from Black students is, “I think differently about my ancestors now.” I think that tells us something. That tells us that they have kind of absorbed the idea that their ancestors were either shameful or not important. Somewhere in that range, right? But we have a very, very ambivalent reaction to the past that we imagined. So to that degree, Black folk need to see heroes. I mean, they need to see the Vernon Dahmer’s who are willing to sacrifice everything he could have had for a common goal. They need to see Medgar Evers, who’s just absolutely adamant that he will not back down, and all of the others. They need those heroes. The problem, though, is that too often heroes get raised to that status, doing things which from certain value perspectives are problematic things. I have the greatest ambivalence about these stories of physical courage and violence because that’s just part of a master narrative about heroes of people who can dominate folk and dominate folk with violence. At the same time, when you’re lifting these folk up, you’re also reinforcing some of the negative trends in the larger culture. So anyway, I just wanted to say, that is a hugely important question. And I guess the way I think about it now is that we have to, on the one hand, lift them up, but on the other hand, encourage young people to be critical about the criteria by which heroes are being defined. I’ll just leave it there — that we have to encourage them to be mindful. Kaler-Jones: I really appreciate that point. Thinking about even asking those critical questions of who gets to be a leader, what are the qualities of leadership. Even thinking about a lot of the literature on leadership doesn’t include youth perspectives on what leadership is. Most of the leadership perspectives are white, male, adult leadership theory. So even asking our students, “What is a leader and who gets to be a leader?” could really illuminate so much about what leadership could be. So, thinking about what you’ve shared, and thinking about a quote that I’ve pulled from your work that really sits deeply with me as we have this conversation and thinking about how organizing represents another tradition of Black activism — “a tradition that places greater emphasis on the long-term development of leadership in ordinary men and women. It is a slower, often less dramatic form of activism in which organizers are pushing other people to make their own decisions, not to look to some external leadership to think for them, decide for them, fight for them.” I think with that quote, we’re going to take a pause here for our breakout rooms. But it also makes me think, too, one of the questions that I often ask my students very much in relationship to what you’re talking about in demystifying a lot of these master narratives, is: Who gets to tell history? Who gets to hold the pen? And what does it look like when we get to write the history books for ourselves? When we come back from the breakout rooms, one of the things that we will dive into a little bit deeper is the current moment and relating the historical context to the contemporary. We are living in history, so how do we really encourage and allow young people to see themselves as the historians of this moment? That’s what we’ll explore. We’re going to jump right back in with a couple more questions that we want to get through, as our time is too quickly coming to a close. So Dr. Payne, many of the current textbooks briefly mentioned the 15th Amendment, the 19th Amendment, and the Voting Rights Act, but treat voting rights as if it was a study process that just ended in 1965. Additionally, those textbooks don’t discuss the organizing in the south, the rich history that you’ve just shared with us, as an integral piece of the history of voting rights, voter suppression, and voter intimidation. Recent elections have shown age-old voter suppression tactics continuing to appear in pervasive ways — including voter ID laws, voter roll purges, long wait times in predominantly Black and Brown communities, polling places being shut down, and voter intimidation. What must we know and teach to provide the necessary context to understand the ongoing struggle against voter suppression in the United States? What did voter suppression and intimidation tactics look like then connected to what they look like now? Payne: That’s one of the easiest questions to answer — the more things change, the more they stay the same. There’s not a whole lot of difference. I mean, some of the extreme violence, so far we have not seen that, not on a mass scale. Some of the ridiculous things — asking people how many bubbles in a bar of soap, how many seeds in a watermelon, which they used to ask as part of the literacy tests and that kind of thing is gone. The traditional ways of disenfranchising Black people also disenfranchise a great many white people. So if you make people pay a poll tax and keep poll tax receipts, a lot of white people aren’t going to be able to do that. A lot of white people are not going to be able to pass a literacy requirement. There’s a sense in which you can argue that many of today’s voter suppression tactics are more racially specific even than the tactics of the past — that is the attack on mail and voting, having observers at certain precincts, putting false drop boxes in certain precincts. All of those are going to be targeted toward particular kinds of racial groups. So, if there’s a difference that we should wonder about, it’s whether or not the degree to which racial groups are targeted is even sharper than it used to be in the past. Other than that, it’s just variations on the same old themes. Kaler-Jones: That is a really great point of how the historical plays a role in the current context. One of the things that you’ve also mentioned in some of your writings is that the term “civil rights” was always a very narrow way to conceptualize the larger struggle. Why is civil rights a narrower term? What does it exclude? Payne: Everybody but Black people. I mean, the movement should be understood as the movement, the long struggle over decades, for African American aspiration, participation in the society, should be understood as a critical part in the shaping and the broadening of American democracy. That means it has impacts on everybody. There are a number of things wrong. Civil Rights are only a part of what African Americans have wanted. It’s only a part. When you say civil rights, it implies the rights of citizenship. It doesn’t say anything about economic equity. The 1963 Washington March was a march on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and the jobs part is typically forgotten. So it leads to situations in which white people might say, “You people have your civil rights. What are you angry about now? You got what the Movement asked for, right?” But the larger point for me is that the movement, as Bernice Reagon said, was “A Borning Struggle.” The movement was not something that merely affected Blacks. In many ways, irony though it may be, some of the primary beneficiaries of the movement of southern white men, who had been impoverished by the racism of the South, and who would not have all of those factory jobs in Tennessee and Kentucky if they were still feudal states. The movement had to end that feudal political state before the sunbelt could be opened up for economic expansion. The last I looked at affirmative action suits, the primary beneficiary of affirmative action suits were educated white women. Not people of color. What did Gregory call the equality society, the demands of Latinx people, the demands of women, the demands of Native Americans, are all shaped by, or to some degree affected by, the fight for gender identity rights. All of those fights are affected by what we call the Civil Rights Movement, and that language does not impart that. The leadership, the tactics, the lessons of organizing for many of the movements of the 1960s came directly from the experience of the Black Freedom Struggle. Kaler-Jones: That is really powerful, to think about moving the term civil rights and how it is so broad. One of the questions that I’m seeing come up in the chat box is around encouraging folks to vote, especially folks that may feel a sense of stress and worry and anxiety, and also just feeling apathetic to everything that’s going on. What can we learn from the Mississippi movement broadly to guide us in the continued fight for the ballot today? What lessons from SNCC can we apply? How does the work that SNCC did then connect to today? Payne: One of the reasons I wanted to stress this issue of the price that people had to pay in order to get us here is that I think it’s a way to address that question. I think the more clearly we understand what people have gone through previously, the more we can look at the obstacles that we have to face and say, “Well, if they could do that, we can do this.” I know from talking to young people that that is a part of simply knowing the history, feeling a sense of respect for the people who made the history, a sense of obligation, and a sense that we waste their sacrifice if we don’t act on it. And so yes, I am not at all unwilling, for the young people who are in my life, who are in my extended family, to do whatever it takes to get them to the polls next month. I’m not trying to persuade everybody. If they can’t be persuaded, I’m threatening people. We’re not going to see a more important election than this one in our lives. For most of us, it’s hard to imagine what can matter more. So, I think we just have to keep hammering that point home, and hammering home the history that has made our lives whatever it is, and our obligation to those people. Kaler-Jones: I love that you talk about knowing the history, because I believe that truth-telling is a form of love with our students. Telling the true history and telling the whole history is a way that we express love. And I think that as we do this work, and as we share this history with young people, getting them to see themselves as the ordinary people that make up these movements is so powerful and life-changing. Another question that we have here is, “Some of the themes that came out of the Mississippi movement were the ability of older activists to make connections with young people, the importance of developing a new generation of activists, the willingness of rural people to defend themselves, and more. Can you share with us some examples of these themes?” Payne: That’s quite a bit of territory, but I can at least touch on some of them. When I was showing the slides, there was one Hartman Turnbow, who was famous for defending his home and family from attack. He was one of the many people who did that, who said, “I wasn’t being not nonviolent, I just defended myself.” For rural people, by and large, they don’t see any contradiction. Non-violence meant don’t be aggressive. Don’t bother people if they don’t bother you. But there was never any question about whether or not they had felt they had the right to self-defense. Charlie Cobb has written a very important point book on that theme. On this issue of generational cooperation, I want to put that in larger terms — what did we not learn to do in the 1960s? I don’t think we learned to keep the focus squarely on democratic practice, both in our organizations and in the larger society. That’s one. Two, I don’t think we learned — you know, people from SNCC always joked about how long their meetings were. Meetings went on literally for days, sometimes. Everybody had to have an opinion. Everybody disputed everybody else. I forgot who said “SNCC people would argue with a lamppost,” but that has been my experience. It is very, very difficult to keep democratic practice at the center of the work. There are all kinds of things — and Ella Baker was so aware of this — inherent in organizations, and especially large organizations, and especially celebrity driven organizations, and especially media dependent organizations, all of those are anti-democratic practices, or tendencies or sources. Keeping democracy at the focus is super difficult. The other thing that is super difficult is to retain the kind of community in which people can disagree respectfully, and then move on together as a band of brothers and sisters, a circle of trust, in the strongest language. How do we learn inside movement organizations to disagree, respectfully. That was a problem in the 60s, and I think it continues to be a problem now. All I can say is it’s a question that we need to be asking ourselves constantly. Kaler-Jones: So many great notes! As you’re chatting, I’m just writing notes down for myself that I can include in my classroom and just thinking about how we move past the master narratives in our teaching, asking the critical questions, examining the leaders that have been typically propped up in the textbook, centering democratic practice at the center of the work, and even including that as part of our pedagogy, and retaining classroom communities where people can just disagree respectfully, even in this virtual age of creating opportunities for debate. I’m thinking about some of the Zinn Education Project tribunals, and engaging and stepping into some of these roles to better understand different folks’ perspectives. But also digging deeper into what the master narratives are, and how we can refute those master narratives. Something else that you’ve shared tonight that is really sticking with me is just teaching the history of resistance, and really centering that in our practice, in our pedagogy, teaching the history of resistance as a core piece of teaching the Black Freedom Struggle. Payne: Your comments make me think something else that we don’t say enough: We should teach the history of resistance, but we should also teach the history of people who opted out. When people didn’t take part in the movement, why didn’t they? How did they explain it? Du Bois has this great quote, simply “Pessimism is cowardice.” If you look across these histories, time and time again, you find people saying “that mess is not going to do any good.” Or today, “this vote is not going to do any good.” But, if we understand both the people who did take part and the people who didn’t — and the people who didn’t at one point in time, but did at a later point in time — that may give us a fuller understanding of how we can move now. Kaler-Jones: Absolutely! I have chills thinking about the power of this. Part of the larger story of refuting the master narratives is also thinking about whose voices have not been a part of the story and why. Why have their voices not been centered in this work and understanding to have a full nuanced and complex picture of what history truly is and then what history can be as we get to create the future? While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Transcript

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was learned

Responses to the question: What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today and what may you do with what you learned?

De-emphasize heroism in the teaching of the so-called civil rights movement.

It was so helpful to be reminded of the many people, not just the bold-faced names, who worked tirelessly — those who sacrificed their time, their positions, and in some cases, their lives.

Leaders are those who develop leadership in others.

Dr. Payne — “…greatest price for change, paid for by poorest people…”

Know your real history.

Knowing the lives of ordinary people who did extraordinary things. It’s on us now.

Power of organizing amongst ordinary people. What I will focus on is the idea that every student has the potential to lead their peers in action. What I must do as a facilitator is identify and reflect back to them their concerns, display to them the risk and ask them the question, allowing for time to consider, do they want to change things.

Telling the story of the individual that is part of the collective. Piecing those stories together.

I appreciated hearing about individual people. I will use this information with my students.

In teaching resistance, we must also teach about those who did not and even those who did not at a certain time, but did later. . .

Validating my memories of the voting rights movement in Alabama in 1965 — and why SNCC was so revolutionary at the time and long term. The unyielding commitment of people who took huge risks to make the world we have today.

Shifting the master narrative to one focused on a more nuanced understanding if a resistance centered narrative.

There are too many to name. But the master narrative piece was a good reminder. I also need to listen to the whole thing again. . . His slides were so illustrative. Centering resistance and the price paid w/o centering the perpetrators and staying steeped in the pain. Being reminded of the changes happening already in the 40s.

The fallacy of waiting for a leader to move the movement forward — the idea that it was often the most vulnerable who did the heavy lifting in the movement

So much stuck with me! I’m continually thinking about those people with some degree of independence who were freer to participate in the movement and the implications that idea has for my discussions with my students. I’m still reflecting on the idea of what makes a hero and how I can work with my students to define and identify their own heroes (or perhaps recognize that the concept of the hero may always be misleading)? I’m also thinking about Dr. Payne’s suggestion that we should teach both the history of resistance and the history of the people who opted out. So many powerful ideas!

Remember participants as well as those who chose not to participate. Don’t focus on the heroic few.

To critically look at the master narrative and who we designate to be heroes.

The work of the movement in the 1940s, prior to Brown, and how massive the movement was before the crackdown by the authorities. . . and that middle-aged women were much more involved than middle-aged men. . . these and other tidbits Dr. Payne shared helped challenge master narratives.

The detailed naming of those whose names don’t make the history books. Also the idea of making leaders not just being a leader.

Judy Richardson was in my breakout room and listening and learning from her was amazing. Love hearing from Dr. Payne. Loved the chatbox. Just EVERYTHING!

For me, the most mind-blowing piece tonight was the idea to reflect on what was not learned in the 60s, and to remain focused on the democratic process.

I was reminded about the importance of women and youth in the movement and learned about particular individuals I didn’t know about. I also learned about the differences in what was happening in the 1940s through Brown and the later 1950s/1960s. This year, I increased the time spent on voting rights in my U.S. government class and used some the resources I found on the Zinn Education Project site. I will incorporate more stories of individuals and organizations who fought and continue to fight for the right to vote.

The story about Vernon Dahmer rocked me — I keep thinking about my economic independence and hope to use it to “stick my neck out” in meaningful ways. I like the myriad ways Vernon supported the struggle: starts the youth league, feeds the SNCC volunteers, loans his vehicles, offers publicly to help with poll tax. In my personal life, I’m taking this to heart.

In my professional role as a teacher in a new school, I am dedicated to teaching this material in my classes. I want to gather up a lot of the people for a mixer, like Septima Clark, who teach literacy and use literacy to make a more just world… into a kick off for a research project in the class I was assigned to this semester: “Social Justice in Literature”.

The importance of telling our own local history.

That Black voter registration increased between 1945 and 1954 and it was the massive resistance to Brown that resulted in a crackdown on registration. Want to work this data into my lessons.

Everything Charles said! Particularly, that it’s as important to teach about those who were not part of the Movement as those who were — and those who once weren’t and then joined the Movement.

The story of Rosa Parks participating in a mass meeting connected to so many other events/issues going on just four days before she refused to move from her seat on the bus. We need to include that web of relationships and events in a full, not distorted, portrayal and teaching of the life of Rosa Parks.

I gained a more nuanced understanding of the interaction of World War II veterans’ return with the increased demand for voting rights in the South. And I also began to grasp how Brown vs. Board fueled white rage, which then led to more egregious voting suppression activity.

It made me think about the power of including specific activists’ stories in my curriculum and stressing that these people were ordinary people.

The importance of teaching the long history and numerous people who contributed to the Black Freedom struggle. It’s not just about a small number of famous heroes!

Payne discussed many activists that I didn’t know about before — couldn’t take notes fast enough — I want to watch the recording of this class! Inspirational to have SNCC members with us tonight.

Discussion about the civil rights movement as a narrow term instead of seeing the movement in broader terms and impacts; also the nuances about those paying the greatest price of voter suppression were the most vulnerable and poor (e.g., their jobs and families being threatened).

The most important thing I learned was the statement from Ms. Judy Richardson about Ms. Ella Baker; ” we were taught that we were not the leaders. We were building local leadership that would survive even our deaths.” That quote will inform my future work. We are developing the next generation of leaders who will carry on after we pass from this existence.

The importance of, while teaching students about civil rights heroes, also guiding them to think critically about the concept of heroes.

Pessimism is cowardice! Dr. Payne is a breath of fresh air in anxious times.

The format

Cierra is a great facilitator, allowing for pauses, which allowed for us to think and appreciate the great nuggets that Charles Payne was offering up

This is the third session I’ve participated in and was the best. Perhaps the one-on-one chemistry of Charles Payne and Cierra Kaler-Jones. Glad to see a high school student in our group.

Loved the opportunity to be in breakouts after the initial discussion/presentation.

Breakout rooms always up the energy, the vulnerability, the connections, the humanity. Thank you.

I enjoyed the invitation to share who we are. Enjoyed the presentation and then the breakout.

I think you are on the mark. Everyone wants more time but sometimes energy begins to wane.

Really liked the mix in the breakout rooms. I would have been happy to have even more time for teaching by Dr. Payne.

I loved my breakout room. I actually wished we had an extra 3 min or so. Mia was a wonderful facilitator.

Today was great! Loved everything, even though the stories were painful as well as inspiring and important to hear.

Loved the breakout group, as always — they energize me. I would have loved to hear Dr. Payne speak even more, but I understand it is an evening session for some and some might be tired after work for a longer session. I loved hearing Dr. Payne tell the stories about people while looking at their photos. Wonderful.

The format was helpful as always! I’m just glad these sessions are back!

The presentation and the breakout conversation, as always, with the Zinn series, are great!

The overall format was great. Good to have facilitators in small groups. I was a little sorry our group lost track of the “what surprised us” angle, even though we talked about some interesting stuff re: hierarchical and everyday leadership models.

Excellent organization (speaker, breakouts, and summary). Adequate time for each segment.

I loved it when we got to all say “thank you” to Mr. Payne.

Additional comments

I love hearing others’ thoughts and experiences in the small breakout rooms!

Thank you! I missed the series in the spring, and so glad that these courses are being offered again. Also great to see friends and co-conspirators!

Thank you very much. Our facilitator was very good with a small group of people.

Thanks as always, the ripples from these classes are ongoing.

I will be looking for Dr. Payne’s books. I’ve learned so much to learn to do more.

Thank you so much for continuing these wonderful nodes of community, education, and resistance!

In my breakout group, initially, people talked about how they teach “unsung heroes” in their classes, but with a little nudge to reflect more on what Dr. Payne said in the session, there was a shift to brainstorming how to incorporate more stories for people who are not as commonly taught in the Freedom Struggle as, say, Dr. King. We talked about Bill’s lesson on the Radical Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, the SNCC Digital Gateway, and the time limit was pretty ideal for this go around!

Dr. Payne made us think of our history in different ways. Outstanding.

Thank you for filling up this teacher with information not found in the textbooks — Dr. Payne fed my teacher soul.

Presenters

Charles M. Payne is the Henry Rutgers Distinguished Professor of African American Studies at Rutgers University Newark. His research and teaching interests include urban education and school reform, social inequality, social change and modern African American history, particularly the Black Freedom Struggle. His books include a co-edited anthology, Teach Freedom: The African American Tradition of Education For Liberation and I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition in the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement.

Cierra Kaler-Jones is the Education Anew Fellow at Teaching for Change through the Communities for Just Schools Fund. She is also a Ph.D. student in the Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy, and Leadership at the University of Maryland, College Park. Her work examines how Black girls use arts-based practices (such as movement and music) as forms of expression, resistance, and identity development.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn