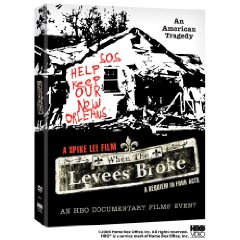

Destroyed house in New Orleans 9th Ward six months after Katrina. Source: Alan Wieder

This is an oral history lesson

just in case the textbooks neglect the truth:

Natural disaster holocausts

are destroying

the poor.

Tens of thousands of bodies

lie in Haiti’s ditches.

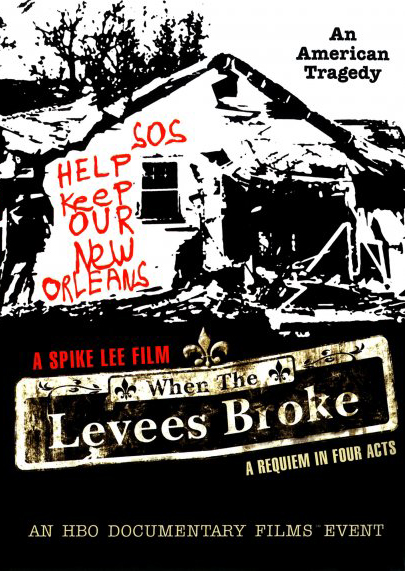

Hundreds of deferred dreams drowned in Katrina’s waters . . .

My high school students stood on stage performing their collaborative poem at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. How fitting that these budding protest poets would be given the opportunity to have their voices rise in the Langston Hughes Auditorium. DreamYard‘s annual spoken word poetry festival gave parents, teachers, youth, and even politicians a chance to witness New York City’s teen poets speak their truth. I sat in the front row, beaming with pride, not only because their performance went off without a hitch, but also because I knew these students meant every word they were reciting. I beamed with pride because I was witnessing the power of arts integration. What started out as a compare-and-contrast assignment for a social issues unit turned into a piece of art. A declaration.

As a teaching artist in public schools, I [Renee Watson] am paired with classroom teachers to teach poetry and to give students an opportunity to experience their academic curriculum through the arts. At the beginning of the school year, I gave my students the ongoing, yearlong assignment to watch the news, to pay attention. We studied Gwendolyn Brooks, who wrote about Emmett Till, and Langston Hughes, whose poetry can be used as a literary commentary on the black experience in America. “Great poets listen to their world and speak back,” I told my students.

As a teaching artist in public schools, I [Renee Watson] am paired with classroom teachers to teach poetry and to give students an opportunity to experience their academic curriculum through the arts. At the beginning of the school year, I gave my students the ongoing, yearlong assignment to watch the news, to pay attention. We studied Gwendolyn Brooks, who wrote about Emmett Till, and Langston Hughes, whose poetry can be used as a literary commentary on the black experience in America. “Great poets listen to their world and speak back,” I told my students.

Our poetry class started off with the sharing of works-in-progress and the reporting of current events students felt passionate about. At that point, headlines and news stories inspired students to write about human trafficking, Chris Brown and Rihanna’s public display of domestic violence, and the HIV epidemic in the Bronx — where they live.

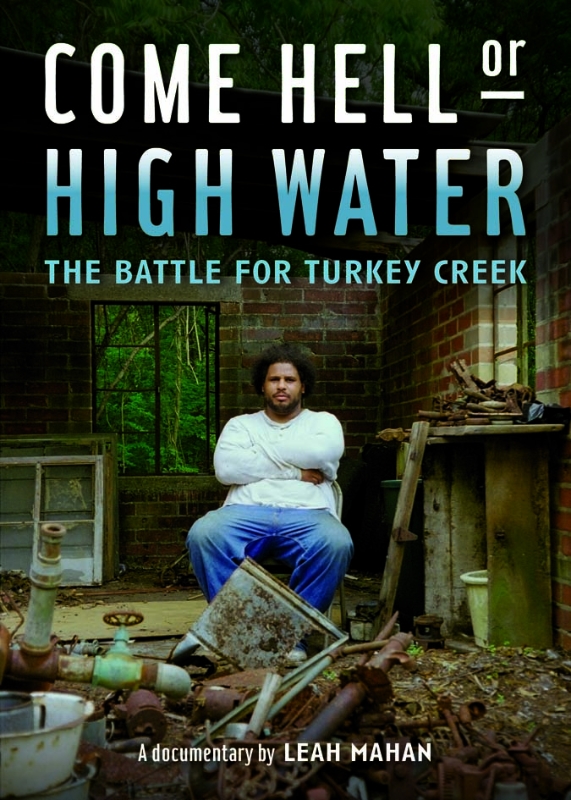

Just after winter break, on Jan. 12, 2010, five years after New Orleans’ levees broke, Haiti’s earth quaked. The next day, every student wanted to talk about it. But how do you talk about something so devastating, so heartbreaking, without repeating clichéd responses like “That’s so sad,” or “Can you believe what happened?”

I encouraged students to look at the situation with empathy, but also with a critical eye. Knowing many of them were working with their classroom teachers on sharpening their skills for writing compare-and-contrast essays, I asked them to apply what they were learning to our poetry class. I posed the question: How do race and class affect the aftermath and recovery from a natural disaster?

Download lesson to continue reading.

Related Story from Democracy Now!

August 27, 2015: Reporting on Katrina, ten years later. In 2005, Democracy Now! was on the ground in the days following the storm that devastated the Gulf Coast, killing more than 1,800 people and forcing more than 1 million people to evacuate. Here are excerpts of Democracy Now!’s coverage of Hurricane Katrina.

This lesson was published in the Summer 2010 issue of Rethinking Schools magazine, “The Power of Poetry.”

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn