On June 12, the weekly People’s Historians Online mini-class featured a conversation between Martha Jones and Tiffany Mitchell Patterson about Reconstruction and issues of citizenship, suffrage, and movement building in the 19th century.

On June 12, the weekly People’s Historians Online mini-class featured a conversation between Martha Jones and Tiffany Mitchell Patterson about Reconstruction and issues of citizenship, suffrage, and movement building in the 19th century.

The session addressed themes of our campaigns to Teach Reconstruction and to teach about voting rights on this 150th anniversary year of the 15th Amendment and an election year. During the mini-class, Jones discussed Black women’s activism and organizing, especially for voting rights. She described her approach to research, which is to “go where the people were.” For example, most authors leave Black women out of the story of the Seneca Falls Convention since they were not in attendance. Jones decided to find where the Black women were at the time of the Convention, bringing them back into the story. Here are just a few reflections from participants on what they learned. (More reflections at the end of this page.)

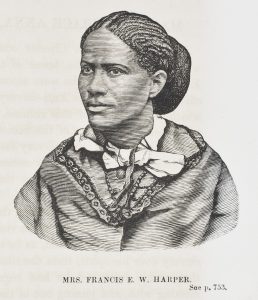

The most important thing I learned today were the stories of Frances E. W. Harper, Mary Church Terrell, and Maria W. Stewart.

I loved the take-away I got from Martha Jones’ intimation that in the past we did not “see” Black women activism in suffrage movement because we were looking in the wrong place, speaks to the power of being grounded in the context of people’s history and knowing or learning where to look. Inspiring and democratizing.

Jones asking and answering the question “where are Black women in the suffrage story?” was extremely profound. The question itself was a reminder that binary narratives about suffrage history — Black men vs. white women — leave out Black women and should be forever interrogated. The class will help me expand my delivery of instruction to students, by always asking the question: who is missing from this telling of history.

Black women were leaders in both women’s suffrage and voting rights for Black Americans. They are often forgotten, but they were powerful organizers who helped push both movements forward.

The most penetrating idea was the idea of “meeting women where they are.” Women were largely forgotten in the Reconstruction Era and in the anti-segregation efforts, and the idea of knowing where to look for them makes the difference between losing a portion of history or learning another perspective.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Tiffany Mitchell Patterson: My name is Tiffany Mitchell Patterson. Welcome everyone, here on behalf of the Zinn Education Project for our session on Reconstruction and issues of citizenship, suffrage, and movement building. Some of you are joining us for the first time, and some of you have participated in one or more sessions. Some of you have been to all of them.

I’m an assistant professor of secondary social studies at West Virginia University. I taught middle school social studies in D. C. and Virginia. I’m also on the board for Teaching a Change, and we coordinate the Zinn Education Project along with Rethinking Schools. So, I’m really excited to be a part of this. The Zinn Education Project has been hosting these sessions, and they have lessons that many of you have used for middle and high school classrooms. If you have not used them, please, please be sure to check out their website.

Before I begin my conversation with Dr. Martha Jones, we want to find out who is in the room and go through our plans for our time together here today. We’re going to do a quick poll to find out how many teachers, librarians, teacher educators, labor and community organizers, students, and family members are in the room. I know many of us are in multiple roles and wear many hats, but think about what your primary role is. Cierra Kaler-Jones will post the poll. So, we’ll give you a few seconds for that. But, as you can see, we have a lot of educators in the house, lots of students, librarians, historians, teacher educators, and people from all walks of life that are joining us today.

So, thank you all for being here. I see the chat is already jumping; please continue to introduce yourself as we go through this. Throughout the session, we want you to use that chat box to post questions, comments, resources, and ideas. Our guest speaker will read your questions and try to respond after the breakout rooms. We’ll also do a short evaluation at the end.

We’re now ready to start our conversation. After about 20 minutes, we’ll pause so that you can meet with each other and talk in small groups and share insights. That’s probably one of my favorite pieces of when we get together is the time to get in small groups and talk to each other. So don’t leave us when that happens. But let’s get started.

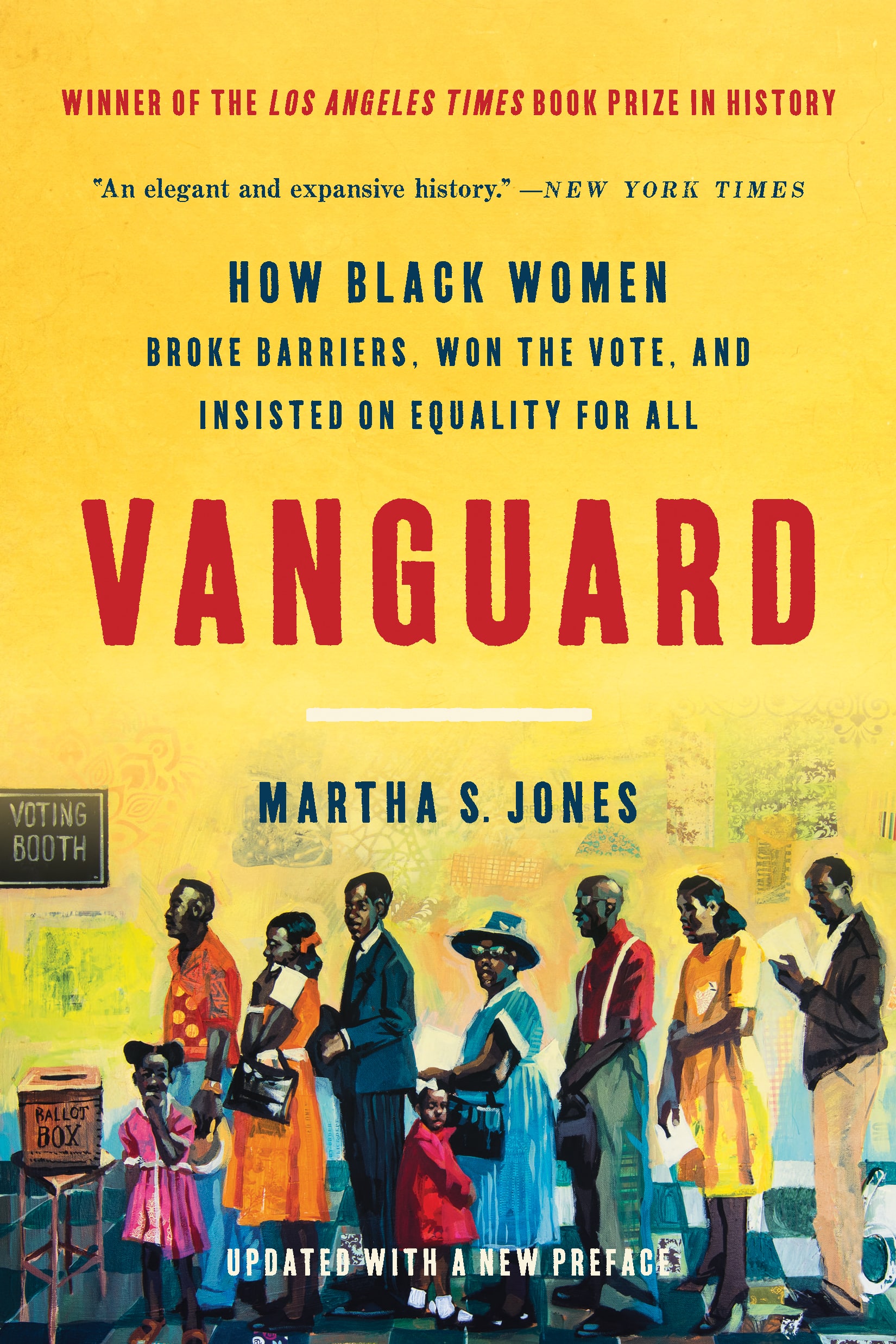

I am so happy to introduce Dr. Martha Jones, the Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor and Professor of History at Johns Hopkins University. Her books include the soon to be released Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. I am so waiting for it to come out in September. It’s on pre-order for me, so make sure you all do that as well. But she’s written other books such as Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America, All Bound Up Together. She has lots of works that she’s collaborated on.

This is such an important history for us to center. So, I thought we would kick this off with thinking about Black citizenship. In your book on birthright citizenship — if you haven’t got it, it’s a great one to have. I found it was really interesting because you explore race and citizenship even before the Civil War. So, I was wondering if you can provide us with a story or two of what citizens should look like for free African Americans? It’s something that we don’t talk about often in schools.

Martha Jones: Well, thank you so much, Tiffany, for joining me and being a partner in this conversation. I’m really very honored. I do want to thank the Zinn Education Project, which for me has been such an important fellow traveler in my work. We’ve crossed paths in the field, we crossed paths in social media, but I feel like we are a part of a really rich and vital community every day. I think, especially in these weeks, I’m so grateful for this series and really honored to be a part of it.

Thanks for asking about birthright citizens. And I think your reaction, if I picked up on what you were saying underneath your comment, was that I think I was like many people who really didn’t think about the story of African Americans and citizenship. Perhaps it began with a notorious Supreme Court case called Dred Scott v. Sanford; perhaps it began after the Civil War; with the ratification of the 14th Amendment to the constitutionalization of birthright citizenship. But I was curious enough to test those ideas.

In order to do that, for me, it was very important to get beyond the abstractions of Supreme Court decisions, or acts of Congress, or constitutions to understand better what citizenship meant in the everyday lives of Black Americans. So I came to the archives of what is now my home town, Baltimore, Maryland. Which, before the Civil War, had the largest community of free African Americans — some of whom had been formerly enslaved people, others of whom had been born free. But they were a community that was already actively wrestling with the problem of citizenship, long before we got to the Civil War.

So, you asked for story and I’m going to introduce my favorite character who emerged during the research. I should say he emerges piecemeal to me. I’m working with hundreds and thousands of case records in the Maryland State Archives, looking at what’s happening every day in the local courthouse. And this name, this man, this character, keeps reoccurring, and his name is George Hackett. Hackett was born in 1807, just as, in the state of Maryland, Black men were losing the right to vote. The word white had been inserted into the state constitution and men who had been able to cast ballots in Maryland had lost that privilege.

[Hackett] is the son of a Black activist who is a deacon in his AME church, an agent for the first Black newspaper in the United States, Freedom’s Journal, but who had lost his political rights in the early part of the 19th century. George lived until 1870, and was in Baltimore at that moment when Black Americans came together from around the country to celebrate ratification of the 15th Amendment, that effort, if you will, to restore voting rights to Black men for the first time in the 19th century, in a thoroughgoing way.

So his life, to me, was fascinating because it was this arc of the story, or one version of the story, of Black citizenship before the Civil War. What I learned about George, and through his life, was that he was part of a community that really relied upon a creative though frustrating set of practices to try and cobble together citizenship. Every time they thought they got to a place where they might have won a point, or might have established a right, they were disappointed and rebuffed. And maybe that doesn’t surprise us. But when you look at that kind of story across decades, what I was able to appreciate was what a harrowing condition it is to be a people whose status and standing before the law is ill defined, always subject to change, vulnerable to political whims, and is taken advantage of strategically and deliberately by people who are looking to exploit or exclude Black Americans from the nation, to make good on that promise that the U.S. is a white man’s country.

And so sometimes Hackett wins. He carries a Siemens protection certificate issued to him by customs officials when he’s a sailor that says he is a citizen of the United States. On the other hand, when the ship docks in a port like Charleston, South Carolina, he’s required to either stay on board ship or be detained in a jail because he’s deemed to be not only a threat as a Black man, but also deemed to be someone without rights. So, the story really is about the ways in which law fails: It fails to do its fundamental job, which is to look at the cultural, political, and legal landscape and determine clearly who people are, where they stand before the Constitution, and where they stand in a local courthouse, and what their rights are. And again and again, birthright citizenship is a story of how law fails men like Hackett and, at the same time, how men and women in Hackett’s community take, if you will, the law into their own hands and craft citizenship, even when so many other people would deny them those sorts of rights.

Mitchell Patterson: Thank you for sharing that story. As we think about the broader journey, the broader struggle, and resilience that has been built in when we think about citizenship and what it even means and who dangles the carrot. You talked a lot about the failure of laws and that kind of ties into my next question, thinking about voter suppression. We’re at the end of the primary season. Just this week, we saw what was happening in Georgia, long lines, we were preparing for a major presidential election, voter ID laws, voter purges, felony disenfranchisement, gerrymandering, closing of assessable polls, people waiting for hours standing in line in order to vote, faulty machines. I mean, the list goes on and on and on.

I think about all those many tactics, and how votes are suppressed, and how they disproportionately impact Indigenous, Black, people of color, and low income individuals. So, what kinds of voter suppression was used in the 19th and 20th century compared to today?

Jones: It turns out that when we look over the long array of U.S. history, that it is a history of voter suppression, that there is a very small window — perhaps between the passage of the Voting Rights Act and then the gutting of the Voting Rights Act in 2013 — where we approach the potential of universal voting rights. But most of our history is a history of voter suppression.

For the early part of the 19th century, of course, voter suppression comes about by explicit and unapologetic terms, which is to say, in the example of George Hackett, Maryland is a state, his community in Baltimore is subject to the state constitution, and when lawmakers insert the word white, they don’t apologize for that. They don’t dress that up. They don’t apologize for it. They are clear that political power in this country is a white man’s business and state laws throughout the U.S. will make that plain in the language of constitutions and the language of state statutes. The revolution of Reconstruction certainly changes the terms of that, which is to say that the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments make Black American citizens by virtue of birthright and guarantee them equal protection of the laws.

The 15th Amendment is going to forbid states from using race as an express criteria for access to the ballots. And white supremacy adapts; it’s the same white supremacy, in my view, that was operating before the Civil War. It adapts to the new conditions of a new constitution and now creates tactics that are neutral on their face — poll taxes, understanding tests, literacy tests, grandfather clauses, whites only primaries, things that don’t appear on their face to violate the terms of the 15th Amendment. But again, Southern lawmakers are open and notorious about their intent to use racially neutral language, and then to use the laws in discriminatory ways to ensure that Black Americans are suppressed at the polls.

And we lived through a long era that we sometimes referred to as Jim Crow, during which this is the order of the day. Law — along with intimidation, violence, [and] lynching — will determine who votes in the United States, and by what terms. We associate, of course, the civil rights revolution with a confrontation with that regime, and another revolution in law, in particular, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which looks to put an end to voter suppression. So, I think it’s important to use this language of voting rights and voter suppression, not only for our own time, not only for special cases, which I think we’ll talk about — which is women’s suffrage — but to appreciate that there really is no moment in our history when voting rights have not been suppressed, contested, and hard fought for. This should remind us that it is always an open question of who votes and by what terms.

Oftentimes, that is a question that leads to the narrowing of opportunities to get to the polls. But, I happen to live in Maryland, where my state lawmakers are perhaps not wrongly proud that we don’t have express voter suppression laws on our books. We just went through a primary election where, without any requirement, without citizens being required to do anything, we got ballots in the mail and we could vote. But even to my state lawmakers, I would say, with all of that, we still don’t guarantee to every citizen of Maryland the right to vote. We don’t put the same impediments in place that we see working in other jurisdictions, like Georgia or Wisconsin, in our sort of most recent past. We still here even do not have a promise, a commitment, a guarantee, like that every American, every citizen, every resident, we’re not promised the vote, even as the bars to voting may be lower in a state like Maryland.

Mitchell Patterson: Wow. I’m still processing. I’m going to need a breakout room for that! So many good jewels were dropped in that, especially in thinking about there never being a time where this hasn’t been an issue. I think that’s something that really resonates with me.

I want to switch gears just a little bit, but I’m still in that vein of voting and suffrage and thinking about Black women within that. This year, 2020, marks the 100th anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment, guaranteeing and protecting women, in reality white women’s constitutional right to vote. Historical milestones offer an opportunity to tell diverse histories that have been erased. Seneca Falls the 19th Amendment are two key points that put women into the curriculum, which is a disservice in general where we have limited women’s history in the curriculum. But, what are some stories that are missing from mainstream narratives of suffrage or the suffrage movement?

Jones: Gosh, we don’t have that long. Maybe just one. Well, it’s important to say because the first histories of women’s suffrage were written by women who were deliberate, foregrounding their own stories, and erasing the stories of many other American women. So we work from a kind of deficit, don’t we? Which it takes me a whole book plus to begin to try and address.

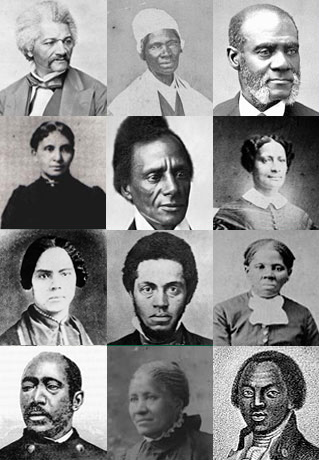

So, there are many things I could say. Let me try just two short ones if I can. One is, historians had for a long time lamented, I think that’s the right word, that they couldn’t find Black women in the history of suffrage. Now, pathbreakers like Dr. Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, of course, came back and went through those materials and recovered the Black women who were indeed essential to that which we call the movement for women’s suffrage. But, even after that work, we were left to wonder where Black women were. Dr. Terborg-Penn recovered a few dozen, but where was everyone else?

And one of the answers, out of my work, is that Black women are in their church communities. I write, in particular about Black Methodist women, AME women, AME Zion women, who were in their churches going all the way back to 1848, the year of the Seneca Falls convention. And when they don’t come to Seneca Falls, what they are doing instead is rising up within their church community, challenging the patriarchy there, and insisting that church women too have rights, they want licenses to preach, they want to be authorized to interpret the Bible, to travel, and to occupy the pulpit. Over time, they will want control of missionary money that they have raised; they will want offices in the church, like the office of the deaconess; they will want to exert the highest authority in their denominations; they will want to be ordained as ministers and to run their own congregations; to be equals to men.

So, when we look for Black women in this early history, we have to go to where they were. And when we go there, what we discover is that they are as concerned as any American woman with the problem of power, the problem of sexism. In their institutions, they were waging these struggles as long as any other community of American women had been.

I promised just a brief second point, which is that Black women don’t practice suffrage activism in suffrage associations. So, once again, when we move away from the suffrage associations that are very much at the fore of the telling of this history, and we turn to an organization like the National Association of Colored Women — the largest political organization in the United States of African American women in the late 19th and into the 20th century — we discover suffragists everywhere; Black women debating, organizing, preparing one another for the polls, preparing one another for that moment in 1920, when some of them will vote. And the reason they will vote is that they have been organizing for that for decades by the time the 19th Amendment is ratified. So they are effective at getting one another to the polls in incomplete but important numbers, even in 1920. Then the same women will use this organizing body to continue the fight for suffrage, taking us all the way to the modern civil rights era. So, I hope that wasn’t too much.

Mitchell Patterson: No, that was perfect, because I also love how you highlight what women were doing in their daily lives, in their communities. These are the stories that are often left out of textbooks, which usually tends to be one or two people, if that. Women’s history in general is limited, but Black women are even further marginalized. My t-shirt, even though you can’t see it, says, “The revolution will be intersectional.” So, I would love for you, as you think about your book that’s coming out, Vanguard, can you dive further for us about the leadership of Black women in getting their own suffrage and how Black women played that role? We would just love to hear a little bit more about Black women’s leadership in the movement.

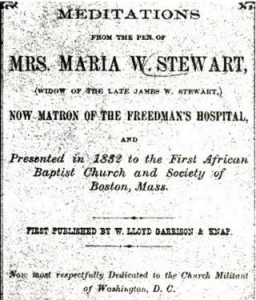

Jones: Sure. When you give me intersectionality I have to take you back to the figure of Maria Stewart. So here we are, it’s 1830, 1831, in Boston, the hotbed of radical antislavery activism. Stewart is a peer to David Walker, whose Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World some of you will be familiar with. But she pens her own manifesto, and it is a primer in the problematic of intersectionality. She thinks Black women are essential to Black politics. She thinks they are essential to liberation, they are essential to power, and she writes and then takes the podium in Boston. Those of you who know the story know that in too short a time she is nearly run out on a rail because she has critiqued both racism and sexism simultaneously, has put on the table for her community, and for its allies, the problem of how to regard Black women as fully fledged members of a radical body politic in the 1830s. The first American woman of any race to speak politics before a mixed audience is Maria Stewart, and she bequeathed to us intersectionality as we come to call it.

Fast forward to the road to the 19th Amendment and I would point to a figure like Mary Church Terrell. Terrell is a fascinating figure in her own right. She’s someone wonderful to study and teach, because her papers are on deposit at the Library of Congress, and they’ve been part of a transcription project. So now we can teach them without wrestling with our students over cursive writing. Terrell’s own words, her own thoughts, are available to us via the Library of Congress. She is really someone who, in the early 20th century, is going to pick up this thread that was given to us by Maria Stewart. She’s going to, importantly, be the first president of the National Association of Colored Women. And she’s going to model a style of leadership for Black women in the 20th century that says, “We are not one issue. We will work as hard to decry and defeat lynching as we will to achieve women’s suffrage and more.” She will tell us that equality but also dignity is an essential thread of Black women’s striving for the vote.

Terrell is like many of the women of her generation, someone who has been assaulted, degraded, terrorized on streetcars [and] on railroads. She is someone who knows the problem of the lady’s car, which is really the white lady’s car, and speaks clearly about the ways in which Black women bring a special set of concerns to any conversation about women and politics, and it includes the right to be free from assault, from indignity, from the threat of sexual assault. Terrell puts this squarely on the table. She’s going to, in some instances, do business with white suffragists; that isn’t going to go away in her lifetime. The project of the 19th Amendment, in Terrell’s view, requires that. But she’s going to do that gingerly, going to do that symbolically, and really invest most of her energy in the very much community-based work that Black club women are doing across the country.

So, this is the organization that is going to sponsor the suffrage schools and the citizenship schools that are going to prepare Black women, but frankly also Black men, who by the 19-teens have also been run out of the polls by Jim Crow. These are women who are going to prepare themselves and their community for that moment when the 19th Amendment’s ratification puts them squarely at the polls.

A small note about Terrell, just to give you a sense of how she’s thinking. Her daughter was born in 1898, and her diaries are online and they’re fantastic. I just was rereading them last night and she tells us all about the challenges of what it is like to be a woman activist and lecturer, traveling, and to have a young daughter at home. We learn how she negotiates with her husband, Robert, around managing all of the things that demand her time and her care as an activist. But in those diaries, she’s also doting on Phyllis, her daughters named Phyllis, and that’s what I want to leave us with. Because she names her daughter Phyllis by no accident. She names her daughter Phyllis as an homage to the 18th century enslaved woman and poet, Phyllis Wheatley. And in this way we understand how Black women are using their own histories to inspire themselves, to buttress themselves, to define themselves in a holistic way.

Terrell is not someone who is distancing herself from the history of slavery and the degradations that Black women endure as enslaved people, even as she herself is an elite bourgeois creature in many, many ways. I think when she named her daughter, Phyllis, Phyllis Wheatley, we learned something about the ways in which for Black women suffragists, their work is part of the pulling on a long and important thread that takes us back, certainly all the way to the 18th century and the trials of someone like Phyllis Wheatley, making that I think a really mighty story for us to explore as we look at the story of the 19th Amendment. Ostensibly, the 19th Amendment really opens the door to a long Black women’s history that might culminate in some ways in 1920, but certainly isn’t defined by anything like a movement for women’s suffrage.

Mitchell Patterson: I just love these stories and I hope educators know that you will get these resources and more next week after this. But, the power that is within the story of the political organizing that is taking place, the social and political clubs, the activism that’s taking place really helps to provide a blueprint for us. We see what Black women are doing and we as educators frame these movements through the lens of Black women; we get that fuller story, we get fuller stories around it.

We have a few minutes, and I’m going to try to get this last question in before we go to breakout rooms. I’m going to Reconstruction because that’s a period, we’ve been working our way through the Black Freedom Struggle through these sessions, and Reconstruction is this period of history that is commonly misunderstood. It’s under-taught, in particular, about the political power and activism of African Americans at that time. And it’s this time of hope and vision and organizing, as you’ve been speaking to, but then also against this brutal white supremacy. So, what are some stories, particularly about Black women, that as educators and librarians and community organizers we can include to help young people and students see these connections between then and now?

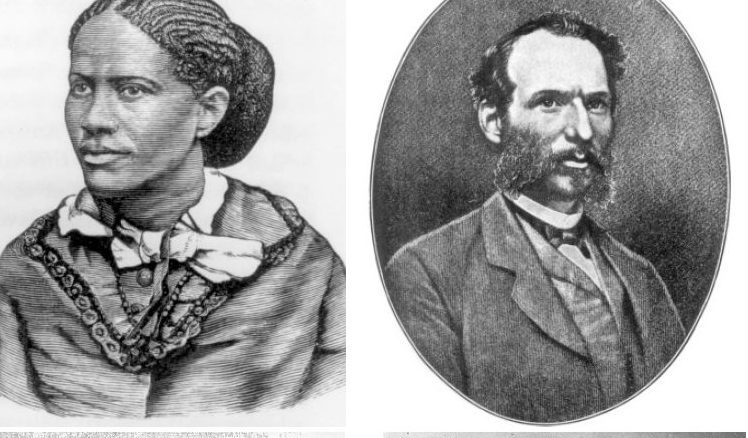

Jones: I’ll make a plea. Please introduce yourselves if you haven’t already acquainted your students with Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper is the sole African American woman to speak during the very important but very contentious meetings that happened between radical activists in the 1860s, antislavery activists, women’s rights activists, as they are strategizing how to respond to the possibilities but also the limits of Reconstruction. Black activists Wendell Phillips, William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, are all coming together under the auspices of the American Equal Rights Association, and they are trying to figure out how to define a political agenda that is ambitious, that speaks to their long standing goals and interests, that speaks to their ideals around universal human equality, including political equality. And yet they are facing, and some of them for the very first time, the perverse exigencies and practicalities of politics. This leads to a series of debates that have often been told as a debate between them.

I’ve often been told there’s a debate between Susan Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton on the one hand, and Frederick Douglass on the other hand. In the end, Stanton and Anthony go with the women and Douglass goes with Black men and it’s a big old rift. This story erases the presence and the ideas of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, who is there for those meetings, and takes an important position that really runs counter to what is being offered up by some of these better remembered folks. Her often quoted line from these meetings is, “We are all bound up in one great bundle of humanity.” What Watkins Harper is saying is, “Have a look at me, the Black woman, and know that I am the measure of this moment. I am the measure of this political culture. I am the test. Because if I can be empowered, if I can be enfranchised, then we have tackled both racism and sexism in this coalition right now.”

Mitchell Patterson: I hate to cut it off right there, but we’re coming back. It’s a good stopping point, as we’re about to head to breakout rooms.

[breakout rooms]

So, a question for you, Dr. Jones: Can you talk about the idea you mentioned at the outset about the abstraction of decisions and the modern era? Gaines, v. Missouri and Brown v. Board seemed to create an additional level of hurdles, and not a magic bullet to resolving issues?

Jones: Absolutely. In legal history, we sometimes call this kind of law “on the books” versus law “on the ground.” And in my work, that kind of abstract decision that I have thought most about is one from the 19th century, Dred Scott v. Sanford. You all may have encountered Dred Scott. The pertinent part, the Supreme Court concludes that Black Americans are not and never have been citizens of the United States; whether they were born free or enslaved, Black people cannot be citizens of the United States. That is a powerful pronouncement. But my question was, what does that do in the lives of Black people? And the answer is: not very much.

When we probe down closer to the ground we discover, in a city like Baltimore, Dred Scott is of no consequence. Local courts and state courts reject the logic of Dred Scott, and even federal courts do not enforce it. So, I think it’s such an important perspective on major decisions to ask not only what do high courts say, but then what happens in the lives of people. We know, of course, that Brown is followed by rampant resistance in the south by white Americans. Nearly every Supreme Court decision has a much more complicated story underneath it.

Mitchell Patterson: That’s great for us to even think about how we expose that to young people, these complicated stories of these decisions. Another question emerged. While this series is focused on the Black Freedom Movement, in particular, we do know that a lot of this work is done in solidarity and in connection with other groups. So, can you discuss the idea of sovereignty as a substitute, or in conjunction to citizenship, and sovereignty as a growing term being connected to recent Black Power uprisings?

Jones: Sovereignty is, I think, a parallel or companion term to citizenship. For most of the 19th century, Native Americans and Black Americans were aware of and watching one another. In the early 19th century, Native Americans were, of course, forcibly removed in that episode that we call the Trail of Tears. Black Americans watch that, and attempt to use citizenship to avoid the fate that they have seen Native people be subjected to. They think that if they are citizens, they will not be subject to the brutal removal that Native people have been subjected to. So there is that back and forth between Native Americans and Black Americans in the early 19th century.

I’ve been very moved, and my thinking has been changed, however, by the work of legal historian Maggie Blackhawk, who’s at Penn Law School. Blackhawk looks at the Reconstruction era and recognizes the consolidation of federal power that results from three new constitutional amendments that are on their face intended to lift up and to enhance the power and the citizenship of Black Americans and Blackhawk says is exactly that same consolidation of federal power fuels the demise of Native nations going forward. The same federal government that we might sometimes admire for its capacity to defend Black citizenship — and we might even call it out for its failure to defend Black citizenship — Blackhawk says is a disaster for Native communities because the federal power is going to be their undoing as we move through the 19th into the 20th century. So, it’s not only that those aren’t the same histories, the tenor of those ideas that Native people are looking for sovereignty and strong federal power, is really the antithesis of Native sovereignty across time.

Mitchell Patterson: Thank you for even attempting to answer that, because that can be in whole sections and theories in itself, as all of these topics are. We would be remiss today if we didn’t think about this current moment that we are in. So, what lessons can we glean from social movement and activism led by Black Americans, African Americans, Black women, that we can take today, as we see in this very moment and movement being also led in that same way?

Jones: I want to come back to the National Association of Colored Women. I mentioned Mary Church Terrell. I certainly should mention Ida B. Wells, but there are many, many thousands of Black women associated with this organization. Why is it important to me today? Because the lesson they teach is that in order to be effective, in order to be powerful, in order to fight power, we have to be nimble. There are moments in which we go to the polls; there are moments in which we go to the streets; there are moments in which we lobby in back rooms; and there are moments in which we organize in community, and more. And part of what characterizes Black women’s political activism, I really think throughout U.S. history, but certainly in the early 20th century, is that kind of nimbleness is a way to sort of read the landscape, to shift, and to move and to learn how to do precisely that. That’s why we don’t recognize Black women as suffragists, because on some days they’re suffragists and other days they’re lobbyists. Then on other days they are confronting power head on, as Ida B. Wells does with her journalism.

So the lesson for me is that these things are not incompatible, that they all are part of a Black political tradition and that the women I write about are as effective as they are, and the legacy they lead us is one that says, you build your power by being nimble, by being versatile, by taking the openings that you can take. And I see that, in a week where Black Americans are both in the streets and are standing at the polls for hours to vote, those are not incompatible. Black women’s history reminds us they were never incompatible, that those have always been part of a shared project. Not always easy, but nonetheless part of a shared project. That helps me make sense of what I see, and it helps me appreciate that our struggle is a long one and we are here for the long game, like the women who came before us.

I was reading Shirley Chisholm today who says, “If Tubman could do it, if Sojourner Truth could do it, so can I.” I think that, for me, it’s essential to return to those legacies in order to fuel the work I do in a moment such as this one.

Mitchell Patterson: That is so powerful. It reminds me of the teachings of my mother, that we have a blueprint, Black women that have come before you that have done this and navigated, and each generation is charged with taking things further. So I would love to end with a story. And I think that’s something that is so powerful, these stories. So, what story or what part of history are you bringing with you at this moment? I know there are many things, but what story illuminates what we’re going through right now in this current rebellion and uprising?

Jones: It’s a personal one. Vanguard is dedicated to my great, great, great grandmother, Nancy Belgraves, who was born in Kentucky in 1808, and was enslaved until the Emancipation of 1865. She raised four daughters, and her picture, you can’t see it, but it’s right here on my wall. Because I know something about what she endured. That’s one. And I know something of what she dreamed up for me, so I keep her picture right here as a reminder of not only what we’ve endured, but also about the things we dream for ourselves, for our families, for our communities, and for our people.

In the broadest sense, Black women never defined their interests as the interests of Black women. They talk about humanity, they talk about humanity, again and again and again. So for me to remember that our cause is that noble, our cause is that large, our cause is that essential that it is speaking to all of humanity every day, and not simply some cheap parody of identity politics. We have always been speaking about humanity. So, I carry that value, that message, that ambition, with me and I have Nancy Belgraves who keeps her eye on me, keeps me doing the work on days when I might not want to.

Mitchell Patterson: Yeah. And it’s just that power, that we’re all fueled by these people in our lives that charge us to continue to do this work and to do more. I have to come back to this because even in the chat, there’s so many questions about even the word citizenship, which has been a theme that we’ve been weaving throughout, and how just contested the very word is itself. So, if you could speak to just that word “citizenship” just a little bit, and then we’ll wrap up for today.

Jones: I guess the first thing to say is that I came to the word citizenship after a long journey. That is to say, in my reading, the term freedom, for example, was a much more common kind of frame. But citizenship emerges from the voices, from the writings, from the speeches, from the lectures, from the commentary of the Black Baltimoreans about whom I write. They land on citizenship because they think it will work, frankly. It’s tactical. It seems to be in the Constitution, even though it’s a little hidden. It seems to have a kind of power and currency in the world that might permit them to overcome the Black laws that are degrading their lives, that might permit them to overcome colonizationists who are organizing to remove them from the United States. They’re looking for a powerful weapon to resist.

And I see today, in our own time, Americans, many of them immigrant Americans, the children of immigrant Americans, who, again, are reaching for that very powerful weapon, which is citizenship. Some of them are being forced to fight in those terms, but others are really reaching for it. So, I think that when I began this project, I was someone who was more familiar, for example, with a human rights framing that really looked to think above and beyond. Like Francis Ellen Watkins Harper, we’re all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity. To me, that’s sort of a 19th century invocation of what we’ve come to call human rights.

But in the archive, in practice, what I encountered again and again was a centrality of citizenship that is constrained, limited, and maybe indeed flawed. Certainly, when we test it in the 21st century, it seems profoundly flawed. Still, I’ll tell you, I defend birthright citizenship. There’s nothing like having a particular sort of foe, like the President of the United States to get you to rethink something like birthright citizenship. But when Donald Trump began to aim for birthright citizenship, I had to rethink it and wonder why he and his folks were so opposed to this. I think it’s in part because birthright is relative to almost any other existing tenet in American law has been relatively, not wholly but relatively, immune from racism. It has protected generation after generation of children born to the despised, and every generation in this country is animated, in the worst sense, by the notion that there are despised people among us. But birthright means that the children of Black Americans, the children of Chinese immigrants who themselves cannot be citizens, are citizens of the United States. It means that in the 20th century, the children of Communist Party dissidents, who are much maligned, are citizens of the United States have a place to stand. It means, after 2001, that the children of Muslim immigrants to this country are citizens of the United States.

I’m one who has thought hard about what this country might be like if citizenship had been up for political grabs, and had been assailable in each generation. Who among us would have been purged? Who among us would have been removed? Who among us would have been disappeared? Those stories exist, of course, but I think birthright has insulated more of us from that sort of fate. So, as I see it, this administration dismantling, whittling away at birthright citizenship, I’m somebody who has come to defend the idea not because it is a panacea, not because it does all the work that we need to do, not because I don’t believe that national belonging, or belonging itself, is a much bigger and more ambitious idea, but because I see people’s lives on the frontlines of that debate, and I’m prepared to defend them in those terms.

Mitchell Patterson: Thank you, thank you, thank you so much for sharing so much. This is just a primer. This is just the start to these conversations that we hope to continue. Please check out the work of Dr. Martha Jones and her forthcoming book, Vanguard, which will be coming out in September.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms, and hear an audiogram from the session below.

Excerpts

Note that this is a rough, largely un-edited transcription.

8:17-9:46, Martha Jones: So his life to me was fascinating because it was this arc of the story or one version of the story of Black citizenship before the Civil War and when I learned about George and through his life was that he was part of a community that really relied upon a creative though frustrating set of practices to try and cobble together citizenship and every time they thought they got too place where they might have won a point might have established the right they were disappointed and rebuffed and maybe that doesn’t surprise us but when you look at that kind of story across decades what I was able to appreciate was what a harrowing condition it is to be a people whose status and standing before the law is ill-defined always subject to change vulnerable to political whims and is taken advantage of strategically and deliberately by people who are looking to exploit or exclude Black Americans from the nation to make good on that promise that the U.S. is a white man’s country.

10:24-11:09, Jones: The story really is about the ways in which law fails. It fails to do its fundamental job which is to look at the cultural and political and legal landscape and to determine clearly who people are where they stand before the Constitution, where they stand in a local courthouse, what their rights are and again and again birthright citizens is the story of how law fails men like Hackett and at the same time how men and women in Hackett’s community take, if you will, the law into their own hands and craft citizenship even when so many other people would deny them those sorts of rights.

12:19-12:27, Tiffany: So, what types of voter suppression um were used in the 19th and 20th century and in comparison, today?

12:27-13:04, Jones: Yeah, it turns out doesn’t it that when we look over the long delay of U.S. history that it is a history of voter suppression that there is a very small window perhaps between passage of the Voting Rights Act and then the gutting of the Voting Rights Act in 2013 where we see the potential right at least we approach the potential of universal voting rights but most of our history is a history of voter suppression.

16:19-16:43, Jones: There really is no moment in our history when voting rights have not been suppressed, contested, hard fought for and this should remind us that it is always an open question who votes and by what terms often times that is a question that leads to the narrowing of opportunities to get to the polls.

16:45-17:56, Jones: I happen to live in Maryland where my state lawmakers are perhaps not wrongly proud of their that we don’t have expressed voter suppression laws on our book. We just went through a primary election where, without any requirement without citizens being required to do anything, we got ballots in the mail and we could vote. But even to my state lawmakers I would say with all of that we still don’t guarantee to every citizen of Maryland the right to vote we don’t put the same sorts of impediments in place that we see right working in other jurisdictions like a place like Georgia or Wisconsin in our sort of most recent past but we still here even do not have a promise a commitment a guarantee he might at every American every citizen every resident we’re not promised the vote even as the bars to voting may be lower in a state like Maryland.

19:56-22:14, Jones: Historians have for a long time lamented — I think that’s the right word — that they couldn’t find black women in the history of suffrage no path breakers like Dr. Rosalyn Terborg-Penn of course came back and went through those materials and recovered the black women who were indeed part of an essential to that which we call the movement for women’s suffrage. But I would want to say that even after that work we were left to wonder where really were whoa where were black women because Dr. Terborg-Penn recovers a few dozen. But where was everyone else and one of the answers out of my work is that black women are in their church communities. I write in particular a black Methodist woman, AME women, AME Zion women who are in their churches going all the way back to 1848 the year of the Seneca Falls convention and when they don’t come to Seneca Falls. What they are doing instead is rising up within their church community challenging the patriarchy there and insisting that church women to have right. They want licenses to preach, they want to be authorized to interpret the Bible, to travel, to occupy the pulpit. Over time, they will want control of missionary money that they have raised, they will want offices in the church like the office of the Deaconess, they will want to exert the highest authority in their denominations, they want to be ordained as ministers and run their own congregations be equals to men. So when we look for black women in this early history, we have to go to where they were and when we go there what we discover is that they are as concerned as any American women with the problem of power the problem of sexism and in their institutions they are waging these kinds of struggles as long as any other community of American women had been.

22:17- 23:08, Jones: A brief second point which is that black women don’t practice suffrage activism in suffrage associations. So once again when we move away from the suffrage associations that are very much at the fore of the telling of this history and we turn to an organization like the National Association of Colored Women, the largest political organization in the United States of African American women in the late 19th and into the 20th century, we discover suffragists everywhere. Black women debating, organizing, preparing one another for the polls, preparing one another for that moment in 1920 when some of them will vote and the reason they will vote is that they have been organizing for that for decades by the time the 19th amendment is ratified.

25:21-26:00, Jones: [on intersectionality] [Maria Stewart] is nearly run out on a rail because she has critiqued both racism and sexism simultaneously has put on the table for her community and for its allies the problem of how to regard black women as fully fledged members of a radical body politic in the 1830s. She bequeathed to us the first American woman of any race to speak politics before a mixed audience as Maria Stewart and she bequeathed to us intersectionality as we come to call it.

32:02-32:23, Tiffany: The power that is within this story of the political organizing that is taking place the social and political clubs the activism that’s taking place really helps to provide a blueprint for us. Like we see what black women are doing and we as educators frame these movements through the lens of black women, we get that fuller story, we get fuller stories.

33:17-36:04, Jones: I’ll make a plea. Please introduce yourselves if you aren’t already acquainted and your students with Francis Allen Watkins Harper. Francis Allen Watkins Harper is the sole African American woman to speak during the very important but very contentious meetings that happened between radical activists in the 1860s anti-slavery activists’ women’s rights activists as they are strategizing how to respond to the possibilities but also the limits of reconstruction.

So Black activists like Wendell Phillips, William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglas, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan Anthony are all coming together under the auspices of the American Equal Rights Association and they are trying to figure out how to define a political agenda that is ambitious that speaks to their long-standing goals and interests speaks to their ideals around universal human equality including political equality and yet they are facing in some of them for the very first time the perverse exigencies and practicalities of politics and this leads to a series of debates that have often been told as a debate between and now I’m doing this I’ll stop I’ve been told there’s a debate between Susan Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton on the one hand and Frederick Douglass on the other and Stanton and Anthony go with the women and Douglass goes with Black men and it’s a big old rift.

This story erases the presence and the ideas of Francis Allen Watkins Harper who is there for those meetings and takes an important position that really runs counter to what is being offered up by some of these better remembered folks. Her often-quoted line from these meetings is, “We are all bound up in one great bundle of humanity.” And what Watkins Harper is saying is ‘have a look at me the Black woman and know that I am the measure of this moment. I am the measure of this political culture, I am the test because if I can be empowered right, if I can be enfranchised, then we have tackled both racism and sexism in this coalition.”

Resources

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was learned

Responses to the question: What was the most important thing (story, idea) you learned today and what may you do with what you learned?

How Black women use their own histories to define themselves in a holistic way. When we frame movements through women our students get fuller stories. Reconstruction is commonly misunderstood.

Continuing to add to my list of especially Black women to learn about and add into my classroom since they have been so left out of what I’ve learned.

I appreciated the point that voter suppression isn’t new. Instead, voter suppression tactics evolve and methods for voter suppression are usually new.

Using the poetry and other primary sources of Black female activists to draw connections to contemporary issues intersectionality, especially when examining the struggles for voting rights.

The power of Black women organizing in groups in churches.

More about the voting rights and the misguided belief that the 19th amendment gave all women the right to vote.

In the small group — reflecting on the ways we search for information — the conversation was compelling.

The names from this time in history that I had not heard or known about before — thought I have taught U.S. History for the last two years. I will do my research and work their stories into my curriculum.

I learned about the ways Maria Stewart and Mary Church Terrell were pioneers in what we now understand in terms of intersectionality. I also learned that Black women’s capacity to shape-shift across history has altered the course of humanity and that we should remember this in our current moment.

Broaden the story of suffrage. I plan to include Francis Ellen Watkins Harper in my lessons now.

The concept that “white supremacy adapts” was really powerful. And that just because rights are gained or court battles are won, does not mean that the fight is over.

Fantastic stories about brilliant women I knew very little about. I loved the idea of the need to be nimble and not just focus on the ballot box. This resonates on an international level as well.

The concept of citizenship as a tactical framework.

To find women’s stories and experiences, look for women in history where they were (churches, social groups, etc.) rather than where they weren’t.

Some nuggets I’m taking away are 1) Black women were present in the suffrage movement but in different ways and communities, 2) “white supremacy adapts,” 3) some great historical figures to look up.

In my breakout session, our facilitator suggested that one way we can change our curriculum content is to begin with the stories of the most oppressed – so start with Terrell instead of Stanton – and build out from there. I am definitely going to employ that strategy in many aspects of my teaching! Yay!

So much!! Hard to label ONE most important idea, but her final thoughts on how citizenship has been used tactically to try and enter into the American conversation were fascinating, as were the ideas about how Black women organizers have consistently argued for HUMANITY.

Stories of Black women who struggled for civil rights, the connection between past and present, and the importance of “citizenship” as protection. I will definitely bring to my preservice teachers; encourage them to develop curriculum on this history.

Can I write — EVERYTHING? I learned a lot today and have more research to do. The role of African American women who were simply fighting for the rights any American should be expected to have, and fought sexism and racism at the same time.

Our history is the history of voter suppression — which means it’s also the history of fighting back against voter suppression. This makes me re-think what it means to live in a “free” country and what our values are when we try to define our freedom.

The story of George Hackett and the arc of crafting citizenship from 1807 to 1870 — I want to use it as a way for students to think about crafting participatory citizenship as we move forward from this moment of resistance.

The work of Black Women’s clubs in fighting against patriarchy within their own communities and in their churches. Also, the idea that the concept of citizenship itself is and has been always contested — which came out strongly in the story of George Hackett who had to take the law into his own hands to struggle and fight to craft citizenship for himself.

New names of amazing Americans are always valuable because any time I can connect a person and their life and story to a concept students connect better — so I am very excited to research more about Maria Stewart, Mary Church Terrell, Phyllis Wheatley, and Francis Ellen Watkins Harper as well as the National Association of Colored Women.

“To fight power, we have to be nimble.” I will keep encouraging my students to look for ALL the ways that engagement must happen to bring about change and help them find their place.

Historians of the suffrage movement have foregrounded only certain groups of women overlooking and insufficiently documenting other women who were active in the fight for the ballot and many forms of justice. Black women were not fighting for themselves alone, but for everyone (i.e. humanity). Thank goodness all is not lost, there is a wealth of stories to recover and share with the world about Black women’s essential contributions.

We have fought voter suppression for centuries. The strength for this fight lives inside of me. Lean onto our ancestor’s resilience, strategy, and love.

To tell richer stories, we have to look for people where they are. Although it is good to know the laws and court decisions, it’s important to pay attention to how they really affected the lived experiences of ordinary people.

“Where are the Black women in this story?” Where do we look for history?

There are essential African American women who worked and fought for political voice and power for suffrage and equality. I am grateful to learn about Maria Stewart and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and naturally need to deepen my understanding of their work. Their stories need to be recognized and highlighted in my teaching of pre-service teachers. The point that white supremacy adapts and creates new tactics, though known, certainly resonated with me. I am wondering how I might weave that as part of an inquiry in my upcoming fall class.

The incredible role of Black church communities and individuals within them again strikes me as a powerful example of people’s history that I must convey to my students.

The format

I love the format — the breakout sessions are really helpful with helping to process the information!

I think the format works really well. I appreciate the pre-workshop reading suggestions and the online format.

Loved the breakout rooms. Though you could have gone on longer, I honestly thought it was a good amount of time that people can put in their daily schedules

As always, wanting more: more from the historian, more time in the breakout room, more from participants. Thank you to all who made this series possible.

I wish there was more time for breakout rooms, but other than that it was awesome

It went by so fast! I loved the stories and being able to be a student again. Just soaked it all up 🙂

Format worked well; our group didn’t have a facilitator, but because of the instructions given in advance, I knew it was okay for me to do that since I had some facilitation experience in other settings. Ran really smoothly.

I like the back & forth Q&A between presenter and facilitator.

I did the pre-reading of the article, so I am glad to have that as a basis for going into the remarks by Dr. Jones. I enjoyed and learned from my breakout room and our facilitator was mindful of time and made it easy for everyone to participate.

I have totally enjoyed the three sessions this season. The first two I could sit and participate with focus. Today’s session required juggling some other commitments and unexpected interruptions. That said, I could still stay sufficiently engaged. Knowing I could access the video and resource materials by next week was great. You all have done a great job selecting speakers and hosts with great questions and heart dedicated to this work and vision for justice in the world.

Additional comments

Thank you, this is consistently an inspiring and very useful 75 minutes.

Thank you as always! ABSOLUTELY THE BEST SILVER LINING OF THE PANDEMIC!!!!!!!!

Thank you for continuing these sessions! I’ve had classes scheduled during many offerings this spring and am so excited to be able to fully participate now that my school year has ended. With all of my planned in-person workshops this summer canceled, I am so excited to continue to have opportunities to connect with other educators and discuss these critical history topics.

This was my first time joining and I’m looking forward to the rest of the series!!

This refuels my teacher spirit after a grueling three months of distance learning.

Thanks for all the work to pull this off. Much appreciated in terms of content and feeling connected to community in the struggle.

Deeply appreciate the work the organizers are doing. The person who hosted the meeting was wonderful, lots of great questions & Jones was very responsive.

I had a great group that really drove the conversation. When it came to teaching in the classroom, all the educators in my group were really determined to work against the “sanitized curriculum” (a phrase brought up in the group) that leaves out voices that should be at the center of conversations for the sake of whiteness.

Presenters

Martha Jones is the Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor and Professor of History at The Johns Hopkins University. She is a legal and cultural historian whose work examines how Black Americans have shaped the story of American democracy. Her books include Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All (September, 2020) and Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America, which examines how Black Americans constructed their legal rights in a world predominated by the view that they were non-citizens without rights. (See Democracy Now! interview with Jones.)

Tiffany Mitchell Patterson is an assistant professor of secondary social studies at West Virginia University. She taught middle school social studies in Washington, D.C. and Arlington, Virginia and is a Teaching for Change board member. Her articles include, What everyone should know about Reconstruction 150 years after 15th amendment’s ratification.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn