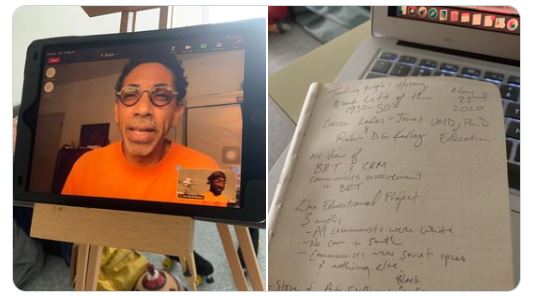

Everyone was on the edge of their seats as Robin D. G. Kelley described and challenged stereotypes about communism in U.S. history in the People’s Historians Online mini-class on May 22. Kelley was in conversation with Cierra Kaler-Jones for a talk on the Black Left: 1930s to the Early 1950s.

Participant Michael Anderson, like most people in the session, listened while taking copious notes.

Kelley proceeded to tell stories about Anne Braden, Lemon Johnson, Claudia Jones, Mildred McAdory, Estelle Milner, Cedric Robinson, the Scottsboro Nine, the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC), the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, and more. Here are two comments from the close to 300 educators and students who participated.

There is such a rich legacy of radical organizing! Each present-day movement and cell of organizing has an antecedent that reaches back to colonization. . . . And the fight for Black lives does require bold, physical, push-back. We can’t “petition” our way to liberation.

I was enthralled listening to Dr. Kelley. His storytelling was so rich and also easy to grasp meaning from.

In this post, we offer a video of the full session, resources recommended by the presenters and participants, tweets, and more participant reflections.

Video

Video of the full event, except the breakout sessions.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Cierra Kaler-Jones: I am so thrilled to be here with you all today. I usually get to be behind the scenes, so it’s nice to be on this side of the conversation today. Welcome to everyone here on behalf of the Zinn Education Project for our session on the Black Left: 1930s to the Early 50s.

Some of you are joining us for the first time and some have participated in one or each of our sessions over the past nine weeks. It truly is a gift to be able to share this time together and I thank you for being in virtual community with us. My name is Cierra Kaler-Jones and I’m the Education Anew Fellow at Teaching for Change, through the Communities for Just Schools Fund. I’m also a PhD candidate at the University of Maryland, College Park studying education.

The Zinn Education Project is hosting this session today and offers free, downloadable people’s history lessons that many of you have used and will reference in the chat box for middle and high school classrooms from the Zinn Education Project website. The Zinn Education Project is coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change.

I am very honored and feel very blessed to be able to be in conversation with and introduce Dr. Robin Kelley. He is a distinguished professor and Gary B. Nash Endowed Chair in U.S. History at UCLA. His books include Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination and Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression, which doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface of his scholarship.

So, as we launch into the conversation, as I think back to my experience in my K through 12 schooling, I didn’t learn anything about how Black people organized before the modern Civil Rights Movement. The Civil Rights Movement wasn’t even referenced as organizing when I learned it in school, but rather was described as a result of a few courageous leaders. Something that we’ve been exploring over these past couple of weeks together. It actually wasn’t until I was in graduate school that I was introduced to the rich history of Black radical tradition. We don’t learn much at all about the Communist Party in U.S. history, and when we do, McCarthyism ensures that it is not positive. So, Dr. Kelley, for our conversation today on the Black left in the 1930s to 1950s, I would love to hear your thoughts on the major miseducation that happens around the Communist Party and Black activism, and why it’s so important to push back towards a different understanding.

Robin D. G. Kelley: Well, first of all, thank you for inviting me. I’m so excited and honored, partly because you know my work better than me. I haven’t read these books in a long time. Also, the Zinn Education Project is one of the most important interventions that we need right now. Like, right now. So I really appreciate this conversation. Let me just begin with this: The most obvious thing is just the sheer silence on the history of the left, period. Let alone the silence on the history of organized labor. Black workers’ struggles in the Civil Rights Movement have been pretty consistent, even to this day.

But let me begin with three basic myths about the Communist Party, and why we don’t know much about it. One myth is that all the communists were white. All 25 of them, right? They’re all white. The second myth is that there were no communists in the South. There was a communist threat, and communism became just an epithet to attack the Civil Rights Movement generally, as opposed to actual people who were members of the Communist Party and its allies. The third myth — if you watch MSNBC all the time then you’ll believe this — that communists were basically the espionage wing of the Soviet Union; that they don’t really exist as activists committed to social justice. Again, the folks in this room clearly have a different take. But this is the common lore.

One thing I should add is that even though the press, historians, the FBI, and McCarthyism have all kind of conspired to erase the legacy of the left, broadly speaking, we have to put some of the onus on Black mainstream leadership. People in the NAACP, like Walter White and Roy Wilkins, spent a lot of time red baiting and attacking people like Paul Robeson and W.E. B. Du Bois. I’m not saying that it was always that case. Walter White of the NAACP who had a working relationship with Du Boi, even though they didn’t like each other, for many years. But the pressure of McCarthyism compelled a lot of middle class Black leadership to basically break ties.

Then there’s another story, which is the story of the anti-Stalinist left, which includes African Americans like A. Philip Randolph, for example, who, of course, was a very important labor leader who came out of the Socialist Party, and had a lot of opposition, not initially, but later to the Communist Party. So those sort of internal conflicts.

One last thing I want to add to this issue is something we don’t talk much about, and that is the anti-Communist folklore, which was really important for generating fear of communism, that communism was associated more with interracial sex and socialism. I mean, that was the bugaboo. The mythology about communism is that white women would be available to Black men under the Communist system, right? That upset white people more than the threat of socialism. In fact, much of the anti-communist rhetoric, which silenced the Communist Party, didn’t talk about socialism as a challenge to free enterprise. That’s not their thing. They were conservative intellectuals who talked about that. But, for the most part, it was why folks were terrified of the threat of Black men having sexual access to white women, of white women being treated as property. So, that’s what’s interesting about the American anti-communist trajectory in culture.

Kaler-Jones: So many good points in that. I’m just reflecting on, as you said, anti-communist folklore and how that continues to come up. It appears in so many history textbooks. I’m thinking about my personal experience, and equating communism with red. It was always Red Scare. I would love to open up another poll to bring some more folks into the conversation. The question is with regard to Black activism and organizing in the decades leading up to the modern Civil Rights Movement, and you can check all that apply here.

Another point that you brought up that I found to be really interesting from reading your work is around the relationship between the Black Communist Party in Alabama and NAACP, specifically around the Scottsboro case, and how that strained a lot of their relationship as they tried to bring it to an international stage.

Kelley: Sure. That’s an excellent question. I should begin by saying one of the bits of information or statistics I discovered that shocked me was that in 1931, Communist Party membership in Alabama and Birmingham was close to 500, and the NAACP had six dues paying members. In other words, the communists probably just dwarfed the NAACP at the local level. But, that said, the Scottsboro case was probably the beginning of a whole series of competitions between the Communist Party’s role in struggling for criminal justice.

I want to say a couple of things about that. One of the foci of the Communist Party was the racist criminal justice system, incarceration, which wasn’t considered mass incarceration, but the incarceration of Black people being thrown in jail for things they didn’t do. And also police brutality. So, the International Labor Defense (ILD) was an organization formed by the Communist Party in the early 1920s to defend what they called “class war prisoners.” Class war prisoners were those who they felt were being railroaded into prison, being attacked by the police, and being surveilled by the FBI because they were fighting for social justice and for labor rights.

It turns out that with Scottsboro — and even before Scottsboro — when the Party got involved and the ILD got involved in anti-lynching campaigns, that’s when the the definition of class war prisoner expanded to include lynch victims. The Party wasn’t the first to fight lynching; I mean, Black people were fighting it all the time. But it’s really fascinating to see how the entry of the International Labor Defense forced the NAACP to take on cases that they would not have taken on. They were reluctant to jump into Scottsboro at first. They were reluctant to jump into other cases involving a gentleman named Willie Peterson, who was being falsely accused of rape in Birmingham.

Later, they got involved in cases in the post war period, like Rosa Lee Ingram and Willie McGee. In these cases, the NAACP was forced and compelled to get involved because the Black left had jumped in and that produced a great deal of tension between the organizations. Some of the most heroic and important figures in the NAACP had taken the position — people like Charles Hamilton Houston — that we need to eliminate the communists, that the communists are a problem.

By the late 1930s, what you begin seeing is Black Communist Party members joining the NAACP in large numbers, and at the local level really kind of redirecting its work. I’m not saying it’s the Communist Party’s initiative that did this, but the NAACP became a mass organization in the 1940s, at the time when its doors were opening up to people who they normally saw as a threat. And those same communists ended up being thrown out of the NAACP in the post war period, just before the NAACP was declared a communist organization by Southern segregationists. They end up being outlawed in the South. It’s an interesting thing.

And I hope we can talk about criminal justice at some point, because I just set this up by saying that our image of the Civil Rights Movement often pivots around the struggle for access to public accommodations — desegregating public accommodations, access to education, the right to vote — and this is all true. And the Communist Party supported these things. But they put a lot of emphasis on police violence and criminal justice that was probably more important than anything in the 1930s, 1940s, and into the 1950s. There are some really good stories I could tell but I’ll save that.

Kaler-Jones: I love that, because we’re definitely going to talk about that. One of the questions that I do have — and I’m excited to have all of this history together — but I want to go back just a little bit. In thinking about a lecture that you gave for WGBH Forum Network on your book Freedom Dreams, you said, “We often talk about why movements fail, but not so much about what they hope to achieve.” The Communist Party hadn’t ventured South before 1929, and in Hammer and Hoe you explore the Alabama Communist Party. So, I’d really love for you to share more about the Alabama Communist Party’s demands at the time and what their campaigns were, because I’m excited to see how that leads us to present day conversation.

Kelley: That’s such a great question. I mean, it’s also important to acknowledge that the Communist Party last year celebrated its 100th birthday. So, 100 years. What I’m saying here is that demands and agendas change over time. The Communist Party in Alabama has a history that begins, as you point out, in 1930.

And last, and even beyond my book, it was almost dead by 1950, but it continued to exist. So, if we take the first part, the early agenda with the early demands, centered around things like fighting for money and resources for the unemployed, this is before the New Deal. There was no New Deal. In the 1930s, there were local organizations giving relief. So they fought for more state and federal relief funds; they fought for jobs for the unemployed; they fought to end evictions of people being thrown out of their homes because they couldn’t pay the rent; they fought for unions to have the right to organize; they fought for provisions for sharecroppers, because in those days, when you sharecropper during the winter you don’t get provisions from the landlord. You have to figure out a way to survive, and people are starving.

And of course, SNCC has a story like this, where people are trying to get provisions for people during the winter. This is an ongoing thing. So, they organized for equal wages for cotton pickers, irrespective of gender or age. They fought against the racist criminal justice system. Then, by the late 1930s and 1940s, their demands changed, or I should say, expanded. They expanded to things like having organizations like the Right to Vote club in Alabama, which the Communists took over. They had the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which a lot of Communist Party members participated in organizing. The Southern Negro Youth Congress was formed and established its headquarters in Birmingham in 1939.

On the legal end, a group of southern white youth got together and what did they fight for? They fought to build a stronger industrial union movement. They fought racism in the armed forces and in federal jobs. They launched a voter registration campaign. They investigated police brutality cases and civil liberties violations and protested those. They waged a campaign to end segregation on buses. This is in the 1940s. In 1944, Louis Burnham, one of the leaders of the Communist Party and leaders of the Southern Negro Youth Congress, formed a Black political party — which we don’t even talk about — under the slogan of nonviolence and non-cooperation. This was 1944. And of course, the Southern Negro Youth Congress was the forerunner of SNCC.

To sum up, in addition to fighting for basic things like fair wages, decent and desegregated housing, education, fair and desegregated education, health care, for racial equality, equal rights for women, they also called on the global scale for anticolonialism (which they saw as a crime against humanity), the end of U.S. imperialist wars (in this particular instance, Korea), and they opposed the Cold War and opposed nuclear war. This is sort of the evolution of their demands. You could see how those sets of demands, which centered around Black working class life and then the masses of Black people, end up being foundational to the demands of the Civil Rights Movement. But, to be fair, if you look at those demands and put them on a list, you can find them in the 1860s, these are the fundamental demands going back to the end of slavery and the beginning of Reconstruction — the right dignity, the right to livelihood, the right to equality and fairness, to equity and safety. So, in some ways, the Communist Party wasn’t this sort of weird stretch. What’s ironic is how little they actually spoke about socialism.

Kaler-Jones: I appreciate so much how you lay out this timeline and within the framework of talking about these demands that we are still, in essence, fighting for. I just want to point our attention back to the poll, as we’re thinking about the timeline that you’ve beautifully laid out for us, Dr. Kelley. In answering the poll question, 75% of us did not learn about this history in middle or high school. Then a number of you, 35%, don’t teach about this history yet, but are here to learn so that you can in the future. And 70% teach this history at home, and 32% teach about this already. Only 11% learned about this in middle and high school. So, I think that’s fascinating within understanding this conversation today, as we’re all here together to learn. I would love to continue to expand upon this timeline that you were laying out for us in talking about the period after 1935, when the Alabama Communist Party came aboveground.

Kelley: By the way, I just had one little thing. I love this poll; it’s so great. I didn’t learn about this stuff in college, except in the library and in our study groups. I come from a background where a lot of people I know who are participating, some of whom I know, come from a very similar background, being involved in a left wing organization, where study groups and self study was our introduction to these things, not the classroom. And I’m old, but I’m not that old. But in the 1980s, that’s how we figured some of this stuff out.

Now, I love this question you ask because it makes me think that I actually had it wrong in my book. What I mean by that is, if you look at the history of the Communist Party on the national level, it is true that the early period was considered the underground period. When the Communist Party was directed by the Communist International, which was the body in Moscow made up of leaders of Communist parties around the globe, they were directed to build a popular front against fascism, partly to defend the Soviet Union.

In Alabama, it was the opposite. The Party was actually overground; I mean it was still underground, but it was much more visible in the early 1930s. In fact, this is when they were having shootouts with police in rural Alabama. This is when they were out protesting in front of City Hall under the banner of the Communist Party. And boy, if I could just get some of the police film clips of those protests from 1932, that would be amazing. But, what happened in 1935, when the Party was directed to embrace a popular front against fascism, they had to turn to the local liberal, to the southern liberals. But southern liberals are not like red curious; they’re not. They’re not necessarily friendly to communism in a way that, say, New York liberals or Chicago liberals might be. These were liberals committed to Jim Crow, who insistently believed that Black people were second class citizens.

What it required was for communists to actually suppress their own agenda, to play down that agenda. Actually, one could argue, and I argue this in my book, they kind of abandon the Black and the white working classes in the south in Alabama in favor of trying to make friends with people who don’t like them in the first place. So, on the one hand, you see these things happen like all these wildcat strikes that take place among relief workers, many of whom are Black women working for the WPA, the Works Progress Administration, working for slave wages. They’re writing letters to Roosevelt saying, “They’re treating us like slaves.” They had these strikes, and the Communist Party at first was helping them organize the strikes. But the labor movement in Alabama is saying these strikes are illegal, these strikes are strikes against the government. You signed an agreement with the government so we’re not going to allow relief workers to strike. We’re just going to let you basically hang. The Communist Party in its attempts to maintain or build stronger lines with mainstream labor leaders and liberals actually began to step back and not support the strikes.

So, in some ways it was a loss. On the other hand, the popular front also opened up space for a different kind of radical movement. I mentioned the Southern Negro Youth Congress and the Young Southerners, a new group of young Black and some white, but mostly Black, intellectuals and activists who converged in Birmingham and adopt a really militant program that did not abandon the working class, but in fact supported CIO organizing, and went to the rural areas and held schools. I mean, what we think of as freedom schools today, or at least that emerged in the early 1960s. You see freedom schools like those formed by the SCLC in the late 1930s and early 1940s. So, it’s out of that antiracist militancy that emerges during the popular front in Alabama that you get groups like the Southern Conference for Human Welfare.

Some of you may be familiar with that organization, the Southern Conference for Human Welfare, which ends up becoming the Southern Conference Educational Fund, which is led by none other than Anne and Carl Braden, who were in Birmingham for a while and ended up in Tennessee and Kentucky. They were amazing, militant organizers who came out of that space of recognizing that you cannot build an alliance with Southern liberals who don’t like you, but what you can do is build a movement that’s deeply antiracist and fight on that score, and bring in anyone who wants to be part of that without having to insist that they’re members of the Communist Party. So, there’s a positive element that came with it, but then the negative was that some of the working class organizations collapsed as their best organizers went into organizations with the CIO.

Kaler-Jones: Wow, that is such powerful history. I’m looking at my next question and I’m so excited to ask this one. One of the pieces of history that often gets pushed to the side is what you talk about when you talk about “infer politics and oppositional culture.” In Hammer and Hoe you say, “Black communists were not blank sheets when they entered the movement and said they were born and reared in communities with a rich culture of opposition, a culture that enveloped and transformed the Party into a movement more reflective of African American radical traditions than anything else.” In your work, you talk about the individualized resistance and infer to politics that Black working class use as opposition to oppression, from singing to theft, dressing up and dancing on the weekends to Black members of the Communist Party bombarding social workers with postcards to push them to give workers relief. So, I would love it if you would share some of those stories of oppositional resistance.

Kelley: Absolutely. I have to give credit, I would not have seen it had it not been for two teachers of mine. One was Cedric Robinson, who passed away a few years ago, who really, his imprint is all over my work. He was the one who kept saying to me, “If you’re trying to figure out how the communists mobilized Black people, you’re asking the wrong questions. Your question is, what did Black people bring to the movement? What is the radical tradition?” In other words, they didn’t need Europe, they didn’t need Marx, they didn’t need any of that stuff to be able to bring it. This doesn’t mean that didn’t matter. It mattered, but that’s not what they brought.

And then George Lipsitz, my other teacher, wrote a book about Ivory Perry, which is a wonderful book called A Life in the Struggle: Ivory Perry and the Culture of Opposition, a beautiful book which talks about a culture of opposition. That is to say that out of his own experiences he figured out what hurt him and his people, what were the barriers and what were the strategies that actually worked so that they could come back the next day and fight.

So, to go back to Alabama, these were very organized people. If anyone says you’re organizing the unorganized, it’s such a myth. These were some of the most organized people on the planet. They’re organized into churches, they’re organized in the lodges, they’re organized in mutual benefit associations, and they were organized in gospel quartet circuits. So many communists came out of gospel quartets, it’s amazing. These Negros could sing and organize! These were the organizations that already pre-existed, and they tapped into those. But they’re not just organizations, they’re cultures, cultures in which the Bible carries way more weight to explain injustice and how to change that. What is the just world? They found that in the Bible, they found it in the way they talked about how the bottom rail shall rise to the top.

They also found a kind of oral culture, an oral tradition that they carried with them. A history. The history of Reconstruction, they didn’t have to read the books. They didn’t have to read Benjamin Brawley, didn’t read any of that stuff, to know from the people who they grew up with, their grandparents, who said, “I remember when we had the vote. I remember when we actually pulled out our guns and protected ourselves from the klan. I remember when we actually exercised democracy and when I was taken away.” That memory is very powerful because it allowed them to see an organization like the Communist Party as automatic allies. It allowed them to see themselves as part of a larger movement.

Let me tell you one story, and then give you some examples. One of my favorite stories, which I talked about in the new preface to the book, involves this man named Lemon Johnson. Lemon Johnson has since passed away. He lived in Hope Hull, Alabama, Lowndes County. I went to go interview him [because] he was involved in the cotton picker strike in 1935. I walk into his house and there’s a hole in the roof. He’s got a picture of white Jesus and a picture of Martin Luther King on his wall, he’s got a bed, a chair, and a table, and I have to sit on the bed. So I asked, “How did you all organize the strike?” and he opens his drawer up and pulls out a copy of Lenin’s What Is To Be Done? and he puts it on the bed. Boom. Then he pulls out a box of shotgun shells, puts it next to the copy of Lenin and says, “Theory and practice. Theory and practice.”

Then he went on to tell me that they were not afraid because they knew that if the landlords would come out and start trying to lynch Negros, they not only had their guns, the men and women to protect themselves. But they knew that if things got really bad that Stalin would send ships across the Atlantic, through Mobile, and send the Red Army to protect them. He said there would be seven ships, and each ship would have contingents of seven men. And with all that said, that’s the culture. That’s the culture. He didn’t believe that, but it’s the stories that carried the weight. What kind of strategies emerge?

So, the story is very powerful of militancy, but when it came to actual grassroots organizing on the ground, this is an organization that knew they could die. They knew they had to protect themselves and defend themselves. In some cases, they did. In many cases, actually, they engaged in armed self-defense. But in most cases, they would do things slyly. When people’s electricity, for example, would go out, they’d come out with jumper cables and connect it to the city streetlights to give them electricity. When their water would be turned off for lack of payment, they would come in and turn the water on with tools. When there were evictions, or potential evictions, they would either approach a landlord with a committee and say, “Look, if you evict this family I can’t tell you what’s going to happen to your house. Because people do need firewood, you know. So, my suggestion to you is that maybe you might want to keep them in the house to protect it, and maybe pay them $1 a month for the work of taking care of your house. It’s up to you.” You find out what’s going to happen, or send penny postcards to social workers who would take away relief from people because the whole system of welfare was always based on policing. These were incredible victories.

Also, the way they would distribute information; going to work they would have leaflets and a worker would open up his lunchbox, let the leaflets out, and then they’d fly and blow everywhere and say, “Well, I don’t know where those came from!” Or people who worked in laundry, domestic servants, would go into houses and sometimes use their identity as a laundress to smuggle in mimeograph sheets to communists, and that sort of thing. All of this was really underground. In other words, they did not necessarily need to put up a front of militancy to be militant, because they wanted to be most effective. And the trickster was part of the trope of an African American culture that they adopted. That’s not always the case, but those are just some of the ways in which they brought the culture to the movement.

Kaler-Jones: I love those stories. My personal favorite is the story of the mimeograph and the Black woman, when doing laundry, bringing them into the homes. There are a number of things that you mentioned that stick with me. Just the idea of memory, that we are seeing ourselves as part of a larger movement, the second piece about theory into practice, so imagining into organizing and fighting for a more just world that’s rooted in justice, joy and liberation. Also the idea that you talk about of radical imagination and using imagining as a collective practice for transformation.

[breakout rooms]

I hope that you had incredible conversations. I know that we did. One of the things that I really appreciated and really enjoyed about this entire series of people’s historians online is the emphasis and the focus on the powerful Black women who have been at the helm of our nation. In thinking about Black women for this next question, there are so many beautiful narratives about the Black women of the Black left, so I would love to invite Dr. Kelley to share more about these women. Women like Estelle Milner, who was a school teacher, Claudia Jones, and Mildred McAdory, who has a connection to a common theme that we’ve been talking about throughout this series, Mrs. Rosa Parks. So, Dr. Kelley, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Kelley: One of the things I’m disappointed about was, I bought this book 30 years ago and wish I had more in depth research on these extraordinary Black women in the Party, both within the Communist Party in Alabama but also extending beyond that.

You mentioned Estelle Milner. She was someone who I actually was inspired to do a little bit more research on and she’s a woman at the turn of the century who became a school teacher. Because of her activism, she ended up losing her job because, by 1940, she ended up being a domestic worker living in Birmingham. But this is one militant, courageous person who was an organizer for the sharecroppers’ union and grew up in Camp Hill, in Tallapoosa County. She had her skull fractured when she was being attacked by mobs because of her organizing work, and she never wavered, she continued to do that work.

I mentioned in the book some women like Helen Longs, a domestic worker and organizer for the Communist Party whose story about being beaten in Fairfield jail mirrors that of Fannie Lou Hamer. You mentioned some other women like Claudia Jones, the Trinidad immigrant, who moves to New York and ends up being really the highest ranking Black woman in the Communist Party. She is probably its most important theoretician, who wrote a very important essay called An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman!, which is a critique of not just race and gender and their relationship to class, but the Party’s on race and gender politics. She is deported and ends up in England being one of the most important organizers in the UK. There are lots of examples of that.

One thing we’re going to end up talking about at some point, I think, is the Southern Negro Youth Congress, which probably had the most dynamic group of Black women leaders, people like Esther Cooper Jackson and Dorothy Burnham. One person who we don’t always talk about, an amazing militant, is named Sallye Davis. Sallye Davis had two daughters, Fania Davis and Angela Davis. Angela, of course, one could argue was a product of this kind of left culture as a child. These were women who were not just extraordinary for their courage and for their willingness to stand up to power, but because their political work put them directly in touch with working class families and middle class families. The emphasis was on improving lives and working class people at whatever the cost.

So, to me, as a future project for new students to go back and find these names, look, figure out who these people are, do deeper research to understand that these Black women were not simply the cannon fodder of the Party, they were not simply running mimeograph machines, but they were also the intellectuals theorizing about how to build a movement devoted to class struggle and the emancipation of all human beings — emancipation from gender, from patriarchy, emancipation from racism and Jim Crow. They thought through these things, wrote about them, lived them, and practiced them.

Kaler-Jones: I appreciate that so much, because I felt that same sentiment as I was reading more about these women. I was like, “I have to dig in more. I have to get more history. I have to know their whole stories,” because, as you talk about, the Party press didn’t really talk about Black women at all. So, it’s fascinating to really start to dig into some of those powerful stories. Can you speak more about how the politics of the 1860s and abolitionism have a connection to leftist politics?

Kelley: I’ve got a censor myself because I could talk about that for three days straight. There are some threads, and I hinted at those threads. Those threads are around what Du Bois called Abolition Democracy, threads around fair wages and the right to organize, threads that centered around the right for Black self determination and Black autonomy. What that means is the right to land, the right to education; not just the right to vote, but the right to representation, and to make decisions about the future.

The vision of the 1860s and 1870s that formerly enslaved people brought to the realm of politics, I argue, was the first iteration of what we call social democracy. If you pick up a textbook you’d think social democracy began in Europe in the 1890s. No, it begins at least in the United States in the 1860s and 1870s, led by Black people. Now, that said, much of what they were trying to do — besides defend themselves and build institutions like churches. You can’t argue that it was socialist, per se, but what you can argue is that wealth accumulation was very, very important. Not inequality, not at the expense of others, but trying to build a basis in wealth for Black people who had had property before. That’s a very radical position. But it’s one that’s specific to that moment.

If you look at the period after 1877, you see a shift in Black radical politics. It’s still people fighting for land, people fighting for the vote, people still having to vote for the Republican Party, but they’re joining other parties, like the Knights of Labor, joining the Greenback Labor Party. They’re joining the registers with an emphasis on class, on wages, on good working conditions, on ownership and control of the means of production. And that’s where you get people like Lucy Parsons, formerly a slave who ends up one of the most important anarchists in the United States.

Jump to the 1930s, and it’s a little different in that land is not as important. It’s not that it’s not important. It’s certainly important for the sharecroppers. But now you see much more emphasis on fair wages, housing, desegregation, what we think of as the other part of social democracy, a strong welfare state that could provide for people. And when I say provide for people, I don’t mean handouts, I mean libraries, schools, institutions, parks, good jobs, protection for people at work, and most importantly, protection for people from lynching by the police and state violence. Those connections and things, of course, go back to the 1860s and 1870s, go back to the beginnings of slave ships. But, there’s some things that are slightly different.

And just one last thing about that. It’s not to say that there wasn’t talk of socialism in the 1870s and 1880s; there was a lot of talk about it. But to talk of socialism in the 1930s takes on a different kind of resonance, because now you have something you didn’t have in the 1880s, and that is a “successful” socialist country. That becomes a model for what socialism is. It’s not a good model, but a model nonetheless. And that shapes the discourse in some ways.

Kaler-Jones: As you’re talking about police violence and state sanctioned violence in this larger conversation, would you share about the infrastructure that was laid by Black communist organizing of the 1930s through the 1950s for civil rights, organizing the Black Power movement, and contemporary social movements today around police violence, mass incarceration, and the ongoing struggle for Black liberation? And how do you consider the relationship between these periods?

Kelley: I’ll begin with one big statement, which is that the Communist Party and the organizations that it spawned — specifically the National Negro Congress, the Southern Negro Youth Congress, Sojourners for Truth and Justice, which is a Black women’s organization, and the Civil Rights Congress — all put racist state violence and the criminal justice system at the top of the agenda. This is very, very important because, again, if we think of the Civil Rights Movement as prioritizing public accommodations, desegregation — I’m not saying that’s always true, but that’s the image we have. For them, state violence, police violence, was most important, and especially for working people.

The Southern Negro Youth Congress, with women in the leadership — I mentioned Dorothy Burnham, Sallye Davis, Ethel Lee Goodman, Minkah Makalani, Augustus Strong — all these, they were protesting police killings of people like Oday Henderson, John Jackson, Timothy Hood, these were the folks who were the Michael Browns and Eric Garners of their days in the 1940s. They formed the Jefferson County Committee Against Police Brutality in 1941. They’re the ones who made criminal justice the main priorities.

There’s one story I want to share real quickly, because it’s just the way it goes back. We know the story through Rosa Parks. Rosa Parks has been like the premier organizer around questions of state violence, violence against men and women. She did a lot of this work early on and she did this work oftentimes through the NAACP and in concert with the International Labor Defense. The International Labor Defense was formed precisely to do this work around criminal justice reform, incarceration, police violence, and lynching.

So, in 1934, the International Aid Labor Defense defended in Selma, Alabama a Black man named Ed Johnson. Johnson was charged with raping a white woman. He was a city employee. And here’s the amazing thing: This is in the midst of the Scottsboro case. The Scottsboro case changed the dynamics because what the Scottsboro case did was change the narrative. They went to the Communist newspapers and the protests humanized the defendants. That is, they pushed against the stereotypes of Black men as violent, dangerous rapists, and against the stereotype of white women as all being pure, virtuous victims, and instead made the state the criminals and Black people being accused of this violence the victims.

So, go back to Selma, [where Johnson] gets arrested. The state or the sheriff has to dismiss the charges because the white woman who they tried to get to accuse him recanted. She says, “He didn’t do anything to me.” In fact, her exact words were, “I will not be like Victoria Price, but like Ruby Bates. I will tell the truth.” Ruby Bates was the person who in the Scottsboro case recanted and said, “You know what, this never happened.” She ends up being a hero of the Communist Party and she goes on tour with Angelo Herndon. Victoria Price was the one who said, “You have to stick with it. These people need to go to the electric chair.”

That’s not the end of the story. The story ends with the sheriff trying to hand Johnson over to a lynch mob. What happens is that the ILD shows up with an armed contingent of ex-servicemen to protect them. What I’m saying is that part of the story of the left’s intervention in police violence is not the people who died and that they protested, but the people who lived, and they lived because they defended them through armed self-defense. All that stuff led to a William L. Patterson’s historic book We Charge Genocide, a book that I’m sure most people are familiar with, which is a compilation since the end of World War II to 1951 of all these cases of police violence. What’s important here is that for them, police violence, state violence, vigilante violence was a form of genocide and genocide that the state was participating in or complicit with. So where did they go with this document? They went to the United Nations. They went to the United Nations, to the Commission on Human Rights, and they did exactly what other left organizations did. The National Legal Congress did the same thing. They submitted a petition to the United Nations saying that the U.S. government is actually violating our human rights and is engaged in genocide.

This was huge. You can’t understand the the Black Panther Party’s position on police violence and state violence, its demand for a UN plebiscite for self-determination, you can’t understand We Charge Genocide or the Dream Defenders, or the wealth of actions and movements, all those movements that emerge putting at the center state violence, vigilante violence. Black Lives Matter comes directly out of these kinds of struggles because, for them, the right to live — not just with dignity, but to actually live — the ending the war on Black people, was the fundamental struggle which connected all the other struggles together. So, that’s how I see it, and that history really needs to come out in order to understand the long, long history of why state violence, and why something like the murder of Emmett Till was way more important than Brown v. Board of Education in terms of stimulating a movement.

Kaler-Jones: Wow. Most of these stories, we don’t teach them in school. Just like you said at the beginning, when you would go to the library and in your study groups as a form of resistance, of reclaiming this knowledge that didn’t get taught in the classroom. As we wrap up our time today, I’m just thinking about resistance against state violence, resistance against poverty, resistance against oppression, against the war and Black people. One of the quotes from your book, I’ll end here on a quote that really grounds me and continues to guide me that I would love to share with everyone on the call. You say, “Resistance is our heritage, and resistance is our healing. Through collective struggle, we alter our circumstances, contain escape, or possibly eviscerate the source of trauma, recover our bodies, reclaim and redeem our dead, and make ourselves whole.” That’s something that keeps me going in this greater fight for justice. Thank you so much for taking time, what a gift it is to be able to be in conversation with you and everyone on the call for your thoughts.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

Here are many of the resources recommended by the presenters and also by participants in the chat box.

Books

All Gods Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw by Ned Cobb as told to Theodore Rosengarten

Claudia Jones: Beyond Containment edited by Carole Boyce Davies

Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression by Robin D. G. Kelley

Left of Karl Marx: The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones by Carole Boyce Davies

Three Strikes: Miners, Musicians, Salesgirls, and the Fighting Spirit of Labor’s Last Century by Dana Frank, Robin Kelley, and Howard Zinn.

Lessons and Textbook Critiques at the Zinn Education Project Website

Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union: Black and White Unite? by Bill Bigelow

Disguising Imperialism: How Textbooks Get the Cold War Wrong and Dupe Students by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca

W. E. B. Du Bois to Coretta Scott King: The Untold History of the Movement to Ban the Bomb by Vincent Intondi

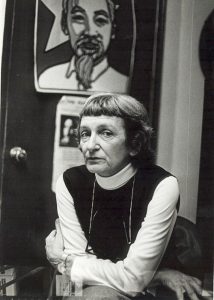

Anne Braden in the SCEF office where she edited The Southern Patriot, Louisville. Photo from Wisconsin Historical Society.

Films and Radio

Anne Braden: Southern Patriot. “A magnificent portrait of the Anne Braden I knew: courageous, militantly anti-racist to the core. Anne Braden changed my life; this film will change yours. — Robin D. G. Kelley

The Great Debaters. Feature film about the debate team at Wiley College in Texas and includes a scene with the Southern Tenant Farmers Union.

How ‘Communism’ Brought Racial Equality to the South. Michel Martin interviews Robin Kelley for “Tell Me More” on NPR.

Salt of the Earth. This classic, powerful film about a miners strike in New Mexico can be used to teach about the intersection of class, race, national origin, and gender.

Scandalize My Name. Documentary about the impact of the McCarthy era on African Americans in the film industry.

Key Events, Groups, and People

|

Lemon Johnson Mildred McAdory |

Estelle Milner Cedric Robinson |

Participant Reflections

Here are some of the responses by participants from the session evaluation.

What was learned.

It’s so hard to pick one thing! The idea of the memory of Reconstruction was so powerful to me. We learn history in these hermetically sealed chunks, and don’t think about how they might affect each other. But obviously southern Blacks would remember Reconstruction and recognize Communist organizing when they saw it as something they wanted to be a part of. SO POWERFUL!

The importance of bringing organizing history from Reconstruction through to Civil Rights and more. Instead of making it seem like events that “just handed.”

Everything. This is one topic that has flown under my radar. I especially loved the “Theory and Practice” story because it’s a true example of resilience and the fight for our rights.

I learned that there were Black Communists in number greater than the NAACP members.

What did Black communists bring to the Party, rather than the other way around. Use this to teach history in totality, rather than the compartmentalized version in standard textbooks.

The agency of the left prior to Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Teaching about activists goals of curbing state violence and advancing criminal justice as core goals of the Civil Rights Movement.

The story of Lemon Johnson — theory and praxis. All the names of Black women in the movement, some of whom I hadn’t heard of before whom I’m looking forward to learning more about.

Lemon Johnson’s story was one that I hadn’t heard. Another is the realization that Black folks brought their culture of organized resistance with them to this movement.

It is very hard to choose. I learned the longevity of resistance and collective and effective struggle of people who were enslaved. I plan to see how I can include some of this history into my Becoming a Social Justice Educator course for first-year college students who plan to become teachers.

The right to live and to end the war on Black People is at the center of every social justice movement for emancipation and liberation. I just really appreciate every bit of history and detail because it is in these narratives that we can reimagine and organize around a more just future. Thank you.

The idea that the Communist party was less about “socialism” and more about advocating for human rights and basic needs.

I was inspired by some of the anecdotal histories that illustrated the broader face of the struggle for human dignity. I was fulfilling to be in a space where people didn’t recoil at the sound of the word “communism” or the ideal of an equitable “welfare state.”

There were so many salient stories and ideas presented today. The first was the lesson that there were African Americans in the South who were Communists (and that Bayard Rustin wasn’t the only African American Communist in the movement). Moreover, I appreciated the language of “anti-Communist folklore.” I didn’t realize that African American Communists have likely intentionally been disappeared from history and textbooks because of the fear that Communism was associated with interracial sex, more than socialism, and a fear of Black men having access to the white female body. Finally, learning about the Southern Negro Youth Congress was also very helpful and the long history of state violence and organizing against the long history of state violence will stay with me. “Resistance is our heritage.”

This talk was so timely as I’m learning more about transformative justice and redefining safety. I used to feel overwhelmed by all the various causes and calls to action, but Dr. Kelley’s revelation that state violence was a priority for all these groups puts things in perspective. I want to find this thread in future research and help uncover that concept in all resistant communities.

So much important stuff! I loved hearing this broad timeline of the Black Freedom Struggle, and how even in the 1930s, organizers were inspired by the movements during Reconstruction. Too often we are taught (and teach!) that the Civil Rights Movement is contained between Brown v. BOE and the Voting Rights Act. I also loved hearing anecdotes about powerful organizers, especially women, like the laundresses who would smuggle literature. These sorts of anecdotes are what really stick with my students, and I can’t wait to pull them into my classroom to show how ordinary people can do extraordinary things, and have been doing so throughout our history!

Wow. I went to middle school in Georgia. I remember our textbook was called Georgia on our/my mind. With the little bit of Alabama’s history that we learned today, my textbook did not scratch the surface of Georgia’s history. Timelines matter, where the timelines start matters, the voices and perspectives amplified matter. Thank you for reminding us to always seek knowledge outside of our textbooks and teacher’s lectures.

Two things. 1. Everyday stories of resistance by Alabama CP members, and 2. The long persistence of resistance to police brutality and state sanctioned violence as a priority of civil rights organizing in the very long term, Reconstruction to now. I’m working on building ways to help high school US history students see patterns over time in US history (re: the “justice” system and land/housing/wealth/property) and both these things can help me provide students stories/models of everyday people resisting — things that even they could do and that have concrete, see-able effects (connecting electricity, postcard threats to landlords). I really want students to see themselves as effective actors, and I really want students to see the vastness of the activism and resistance to larger systems of oppression. And this, hopefully, allows them to see movements like Black Lives Matter or Criminal Justice Reform as not new things or anomalies, but as historically-rooted, natural outgrowths of the past.

So much — took three pages of notes! But loved the story-telling (Lemon Johnson!) and the idea that the culture and organizations of the Black community influenced the way the CP operated in the South. Also good reminder that the Black left in the CP was primarily based in practice, not ideology (which concerns me when I listen to the jargon of *some* of the Black left today). And . . . the memory of enslavement and Reconstruction (“they didn’t have to read DuBois”) . . . and so many connections to the kind of organizing we were doing in SNCC in terms of basing the organizing on the actual needs of the communities we were working with. Shoot — I learned so much from Robin in this short session that I can’t even list it all!

There were many important stories and ideas shared by Dr. Kelley, but one theme resonating with me was the importance of stories and the role of memory in teaching and organizing for freedom in the radical tradition. Communist organizers in the South during the end of the Populist Era used “tropes of the trickster” to create engagement in participation. “Stories that carried weight” galvanized communities to action, politicizing, educating, and inspiring urgency and activism amongst working class Southern African Americans. What may I do with what I learned? As a high school teacher of social studies and humanities, I am further committed to always inject stories of resilience and resistance when teaching events of extreme oppression, violence, and trauma; that people by nature are always in conversation with another and within that dialecticism, victimhood is never stasis or singular, but coupled with a people’s agency to resist and dissent their conditions, as well.

So much great information; hard to choose. I was inspired by the way folks brought organizing experience from churches, lodges, mutual benefit associations, and gospel quartets (!) into the movement — seems like a great model for today.

The format.

Having attending many sessions now, I really appreciate the format every time!

Excellent format. Pre-reading options. Excellent and engaging speaker to introduce deeper thinking and consideration, time to break it out into smaller groups for discussion and bringing it back.

Terrific use of the rooms. I appreciate the structure, the format, the content.

I appreciate the increase in time and structure for breakouts! Could we, by chance, have two more minutes?

The interview format worked really well for me. The breakout facilitation worked great to hear others’ views and to put my thinking together.

I was concerned about the breakout session at first, but it actually helped me process some of the information and make meaning of the details that we learned. I don’t have any complaints or suggestions for improvement.

The breakout room this week could have lasted for a long time. There was a lot of energy in that room I could have learned from.

The chat box is amazing but since there are so many participants, I was distracted trying to keep up with the presenter and the chat! But that’s a good problem to have.

The format was excellent. Although I first thought twelve minutes was too short, it acted as an momentum maintainer, and led to more questions — always a good thing.

I loved the inclusion of the poll and the use of breakout rooms to give space for conversation. It would be nice to have a longer breakout session. We only really got through 1.5 questions.

Breakout session was too brief!

Think this should be 90 minutes long so can have more time in breakout rooms.

Format was excellent. breakout groups spaced out the content/listening and were the right length of time.

The format was incredible! The presenters were incredibly engaging, and the breakout groups were a perfect way to digest and reflect on the material. The size of the group was great, and having questions after the group was really effective.

Breakouts were just a hair too short with the number of participants; I think most folks would be fine with going until 3:30? Chat box is always impossible for me to follow . . . hope it comes with the recording!

I see the format improving every week, which is such a feat because distance/virtual facilitation is hard. The group is over 200 people and yet the learning feels so accessible and personal.

Loved the size of the breakout groups for this conversation. It is so wonderful to be able to chat with such a huge variety of people — both times I’ve had high school students in my chat and have loved seeing them there and hearing their thinking.

I thought the format was great. I would be willing to go for 90 minutes if we could have a longer breakout session — I found it really useful to hear from other people to understand their perspectives and how they planned to use the info.

One of the better run webinars I’ve been to, and to have any kind of breakout group when there were 200+ participants is incredibly impressive. I’ve been running tech for study groups of 20-30 people and it’s so chaotic!

Additional comments.

This was amazing. I have another book to add to my reading list.

This routine has really been helpful to me professionally and mental health-wise during this time!!!!

Amazing work. This is such a great series.

Thank you for organizing these Freedom Friday’s sessions! I have learned sooooooo much over the course of these Fridays. Today’s session was even more meaningful for me since I knew so little about the Black Left. Also, Cierra did a great job facilitating the conversation.

WILL THESE ONLINE WEEKLY SESSIONS CONTINUE AFTER COVID? I HOPE SO!!!! AS ALWAYS, A HUGE, HUGE, HUGE THANK YOU! FOOD FOR AN EDUCATOR’S SOUL.

What an incredible opportunity — it was a nice, bite-sized bit of info that allowed me to identify new topics to study without overwhelming me. I really appreciated the opportunity to process with others. I could hardly believe that it was free!

This was amazing! It is good to be reminded of all the things I do not know, and this was exactly that. I was exposed to so many new stories and ideas. I am excited to continue researching these topics and to find ways to use this history to contextualize current events for my students.

This was a totally fascinating and energizing session! I can’t tell you how much I learned! Plus, it gave me the energy to do the pile of work I have on my plate on this rather overcast day. Thank you Robin . . . and Cierra . . . and all the ZEP folks for organizing this. It really was a wondrous session!

Thank you for this session — it was brilliant. During the breakout room session a participant shared his experience teaching this specific era and shared, “I had only taught them as victims of Jim Crow.” There was a moment of reflection for everyone in the group. With that, thank you for the work that you do.

Presenters

| Robin Kelley is Distinguished Professor and Gary B. Nash Endowed Chair in U.S. History at UCLA. His books include Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination and Africa Speaks, America Answers!: Modern Jazz in Revolutionary Times. Kelley’s research includes the history of social movements in the United States, the African Diaspora, and Africa; Black intellectuals; music; and more. |

| Cierra Kaler-Jones is the Education Anew Fellow at Teaching for Change through the Communities for Just Schools Fund. She is also a Ph.D. student in the Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy, and Leadership at the University of Maryland, College Park. Her work examines how Black girls use arts-based practices (such as movement and music) as forms of expression, resistance, and identity development. |

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn