By Cierra Kaler-Jones

Despite a heavy windstorm that ripped through the Northeastern region of the country that caused internet connectivity challenges for many students in Bethany Hobbs’ social studies class, they eagerly met on Monday, April 13, to share abolitionist autobiographies they wrote as part of Bill Bigelow’s ‘If There is No Struggle’: Teaching a People’s History of the Abolition Movement lesson. In this role play, every student portrays a member of the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS), an organization founded in 1833 that aimed to end slavery in the United States. Each student wrote an autobiography of how they came to be an abolitionist and detailed how their commitment to refuting the 200-year-old institution began. Hobbs encouraged the 9th- and 10th-grade students to choose and examine their identities — gender, age, race, social class, and geographic region — while crafting in-depth narratives to deepen their understanding of the individuals who persisted in the fight to radically change society.

Despite a heavy windstorm that ripped through the Northeastern region of the country that caused internet connectivity challenges for many students in Bethany Hobbs’ social studies class, they eagerly met on Monday, April 13, to share abolitionist autobiographies they wrote as part of Bill Bigelow’s ‘If There is No Struggle’: Teaching a People’s History of the Abolition Movement lesson. In this role play, every student portrays a member of the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS), an organization founded in 1833 that aimed to end slavery in the United States. Each student wrote an autobiography of how they came to be an abolitionist and detailed how their commitment to refuting the 200-year-old institution began. Hobbs encouraged the 9th- and 10th-grade students to choose and examine their identities — gender, age, race, social class, and geographic region — while crafting in-depth narratives to deepen their understanding of the individuals who persisted in the fight to radically change society.

These are a few of the prompts that were shared as a guide for how students might prepare their autobiographies:

You escaped from slavery. You know from your own experience the horrors of being enslaved.

You are a free Black person living in the North. Although you have never personally been enslaved, your mistreatment in the North has sensitized you to the plight of Black people everywhere.

Your father was a slave owner. You witnessed firsthand the conditions of enslaved African Americans.

To spark deeper conversation between students, Hobbs placed students into four breakout groups in Zoom. She encouraged them to share their autobiography aloud to their peers and then the rest of the group members affirmed one aspect of the autobiography they liked or that stood out to them. Students presented moving accounts:

My name is Mabel Hillington and I’m a former slave. I live with a few other freed people. When I was young, I was taken from my family and the other slaves I worked with taught me to work at the pace everyone else was working to protect ourselves from being overworked. The slaveowner would yell at us and tell us we were working too slow. One night, I, among a few others, slipped away in the night. At the time, the Fugitive Slave Act made it easy to get people back on their plantations, so I had to be careful.

My name is James Mormon and I’m the son of a slaveowner, Max Mormon. Until I was 16 years old, I never thought much of the slaves that lived on our plantation. However, the day after I turned 16, I saw my father beat a woman and her child. I witnessed firsthand the brutal violence of enslavement and I made sure that after that I would stand up for enslaved people.

After writing and sharing their autobiographies, the next section of the lesson builds on students’ understanding of abolition and asks students to discuss the dilemmas and challenges that the AASS faced. Some of those questions from the lesson included:

Should the AASS support “colonization” schemes to send people freed from slavery to Africa?

Should the AASS spend time and money opposing racial discrimination in the North as well as attempting to end slavery in the South?

Should the AASS support efforts to gain greater equality for women?

Should the AASS support armed enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act?

As students returned back to the main room, Hobbs left students with a question to think about in preparation for their next class meeting,

What do you think (in your character) is the best course of action within that situation? Include evidence as to why you think that’s a good idea.

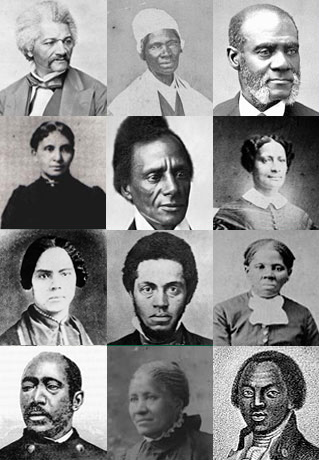

For the next meeting, Hobbs told them they would be put into three groups to discuss the different choices for the movement while remaining in character and considering what the abolitionist they were embodying might decide. Each group will report out on their actions and then share why they came to that conclusion. At the end of the unit, students will read a selected piece from Teaching a People’s History on Abolition and the Civil War to be able to compare what their group came up with to what actually happened in history.

As Hobbs was explaining the next steps, Bill Bigelow, who Hobbs invited to observe students sharing their autobiographies, joined the conversation and provided some words of inspiration:

We are building a legacy of activism. We’re not just checking boxes in lessons and also not checking boxes in history, but we’re seeing how the past is connected to the present in so many ways. What is the relevance of what is going on right now? What does it tell us about this particular moment?

Although Hobbs is allotted only one hour a week to set up a virtual classroom space, she ensures that she not only provides interactive ways for students to grapple with a difficult history and its connections to the present but to check in on student wellness. One of the challenges she shared with me after the lesson is that some students aren’t able to fully connect to the internet because of the rural region they live in and some will only be able to connect with both their sound and video off. Because of this, she worries about them feeling disconnected, so she tries to provide as much support and encouragement as possible.

She ended the class with these encouraging words:

Don’t stop, keep going! The work that you’re doing is so important and makes a difference. I appreciate you showing up today! What will we create as our path forward?

Cierra Kaler-Jones is the Education Anew Fellow with Communities for Just Schools Fund and Teaching for Change. She is also a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Maryland – College Park studying minority and urban education.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn