We waited a long time for those folks to do something to improve our schools, but they let us down and so we have decided to do the job ourselves. — Jefferson High School student, 1968

The quote above opens Jeanne Theoharis’ chapter in A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History on young people in the Civil Rights Movement. That chapter also formed the basis for her People’s Historians Online conversation with Rethinking Schools editor Jesse Hagopian on April 10, 2020.

The quote above opens Jeanne Theoharis’ chapter in A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History on young people in the Civil Rights Movement. That chapter also formed the basis for her People’s Historians Online conversation with Rethinking Schools editor Jesse Hagopian on April 10, 2020.

This was the second in our series on the Black Freedom Struggle: From Reconstruction to the Civil Rights Movement.

About 150 people joined the discussion, including teachers, parents, students, historians, and community activists. Jeanne talked about the role of teenagers, including Barbara Johns, Claudette Colvin, and the students in the high school walkouts. She noted that many of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee activists were teenagers when they took on organizing in places that everyone else deemed impossible.

Contemporary Youth Activists

To highlight the ongoing role of young people, Jeanne and Jesse welcomed two contemporary high school activists: climate justice and educational equity activist Karma Selsey of New York City’s Teens Take Charge and Jaeden Thomas, a member of Seattle’s NAACP youth council. Selsey talked about a campaign to pressure the mayor to provide students access to enrichment opportunities over the summer. The petition was posted in the chat box and signatures poured in from the session participants. Thomas talked about the fight for ethnic studies in Seattle Public Schools and suggested people follow @Wastatenaacpyouth on Instagram.

Recording

A recording of the full session (except for the breakout rooms) can be viewed below.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: I’m happy to be in conversation today with our guest historian and author Jeanne Theojaris. She got in touch with me last year to help; she wanted to speak to the Black Student Union at the high school that I work at because she is creating a young adult version of her book, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks. She wanted to get student feedback and input about how to best translate her book into a YA edition. That was an incredible experience and opportunity for us to work with her on that project throughout the year. So, I want to welcome Jeanne Theoharis.

Jeanne Theoharis: Great to be here. I’m excited for our conversation today.

Hagopian: No doubt. Me too. So, let’s just jump right into it. I want to start with the master narratives that are told about the Civil Rights Movement, because I think there are so many things that we are taught incorrectly about about the Civil Rights Movement. So, there’s a master narrative about the Civil Rights Movement, that it was the product of great men, and you have a chapter in your book about the great man myth and you take it down so brilliantly in many ways. But, I think we should acknowledge there are certainly great men who were part of leading the Civil Rights Movement — Martin Luther King, Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael), or Bayard Rustin, who often gets left out of the discussion of the great men because of him being gay. His sexuality has often meant that he’s invisibilized in the movement.

But there are several things wrong with this master narrative. First, it often leaves out the leading role of women in the movement like Fannie Lou Hamer, Diane Nash, Ella Baker, Septima Clark, Jo Ann Robinson, [and] Rosa Parks. I mean, we could go on and on about the women who really organized and led the struggles all across the country. But it also erases the collective nature. When we say that the changes were made by great men here or there, it erases the collective nature of the struggle and the collaborations of millions of people whose names we don’t even know who are critical to winning the advances of the Civil Rights Movement.

I think what we want to focus on today is the fact that this great man myth misses the critical role that young people played in the movement. So, I’m hoping you can talk about the master narratives about the Civil Rights Movement, and how they’re used to both obscure the role of young people in the movements and also how the Civil Rights Movement has weaponized, as you say in the book, against young activists today.

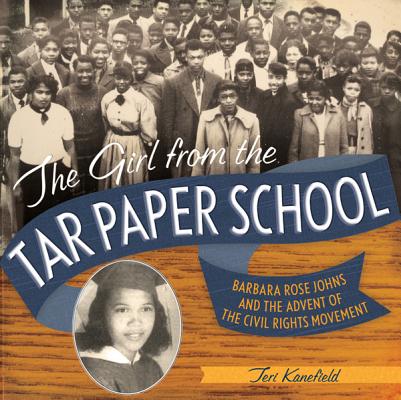

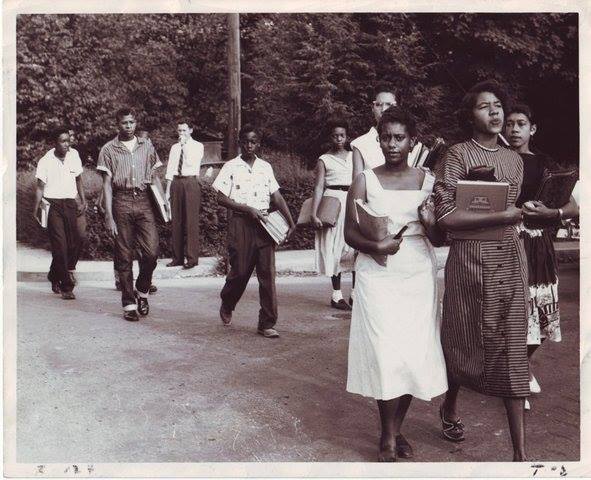

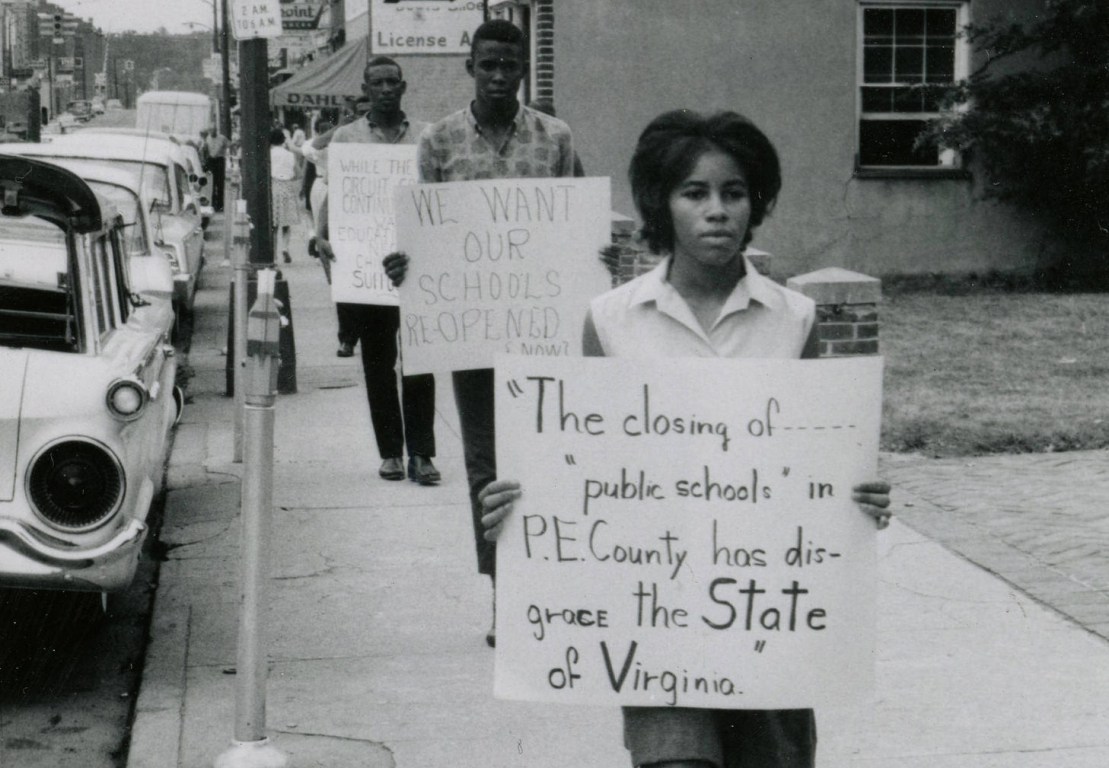

Theoharis: I think one of the ways we really get the Civil Rights Movement wrong is that we miss, at so many key junctures, how young people take it forward and take it forward, at times, against the wishes of their parents, against the wishes of their teachers, against the common sense of adults in the community. So many moments that we even have heard of actually have young people at the lead. I want to talk about a couple. The first is Brown v. Board of Education. I would bet everyone in this class today has heard of Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 Supreme Court decision. That case is actually the product of five cases that went to the Supreme Court. But here’s a case, it’s actually a number of cases rolled into one, so Brown has five cases. One of the cases in Brown, a case that came out of Prince Edward County, Virginia, actually began by a high school student strike, led by a 16-year-old by the name of Barbara Johns.

Hagopian: Barbara Johns is just incredible. She’s incredible.

Theoharis: Part of what’s really interesting about Barbara Johns and her friends is that some of her friends are working at the white high school, like that’s their job after school. They realize that the white high school in town, and this is in Virginia, is much nicer than their high school. Barbara Jones thinks that’s very unfair and she thinks, well, we should go on strike. They go to Mountain High School, so they decided to organize a strike. They called the NAACP for help and the NAACP, the national office, decided to send down a couple of lawyers to basically tell these young people, “Don’t do that. You’re going to just get in trouble, you’re going to get hurt. This is not the place to do it’ it’s going to be too violent.” And these young people are just not deterred.

So these lawyers in the NAACP come down, and they can’t stop Barbara Johns. They can’t stop these striking students. In fact, these striking students turn the NAACP lawyers around and basically this becomes one of the cases in Brown. So the lawyers and the students and their parents agreed to be a case to push forward this challenge that the national NAACP is now mounting against school segregation. But it starts with high school students because their high school wasn’t equal to the white high school in town. Except that’s not how we learn the story of Brown. We don’t learn the story of Brown as partly a story of the courage of teenagers.

Hagopian: Yeah. It seems like, of course, we can’t learn about it in terms of the courage of teenagers, because the way that we’re taught to understand change in society is we have to leave it up to the experts. So, the Civil Rights Movement was launched by lawyers who negotiated this in court. In fact, when we dig deeper, that story is just brilliant about how teenagers led a walkout that was really one of the catalysts for the entire Civil Rights Movement. You write in A More Beautiful and Terrible History, which everybody should get this book that just systematically debunks all of the master narratives of the Civil Rights Movement, but you write, “Even though many civil rights memorials are aimed at uplifting youth, the central role young people played in the Black Freedom Struggle, from Brown to Birmingham to the Los Angeles blowouts, is often omitted. So, maybe you can tell us about some of those other struggles as well?

Theoharis:. I think sometimes the Civil Rights Movement gets weaponized against us. Today, if you do learn about the role that either high school students or college students play in the Civil Rights Movement, now the edges are sanded off. So it seems like everybody supported them, when, in fact, at the time, a lot of adults found their confrontational activism scary. They found it to not be the right way to go about it. Similar criticisms waged against Black Lives Matter [activists] today were waged against these young people, whether it was Barbara Johns, whether it was the student sit-ins in the 1960s that lead to the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, whether it is high school student strikes — and we’re going to talk more about that — many times when young people take this more confrontational action, adults are like, “No, no, no, no. That’s not the right way to do it.” Similar to the criticisms we heard about, and we continue to hear about, Black Lives Matter — “You’re not going about it the right way.” And I think that’s very dangerous, because I think it both misses how the Civil Rights Movement actually proceeded and the tactics that actually push the movement forward. Not being honest about the ways that, even during the Civil Rights Movement, lots of people were like, “No, no, no. That’s not the right way to go about it.” But young people pushed forward anyway. And certainly there were older people who were supportive of that. So, as you mentioned, people like Ella Baker, very much Rosa Parks, mentored younger activists because they so appreciated that spirit, that energy, that militancy. It’s not that there are no older people who are with these young people, but there were also older people who were like, “No, no, no, don’t do that like that.”

Hagopian: Right, absolutely. Do you want to tell us about a couple of those other stories, like Birmingham?

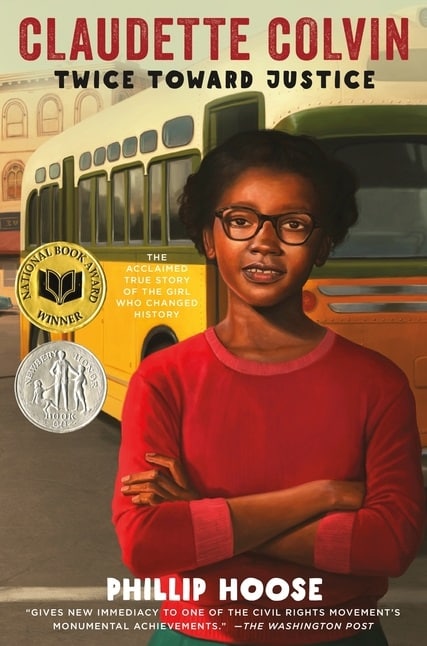

Theoharis: Well, let’s start in Montgomery, because I can never get past Montgomery. Most of us, I think, have now heard of Claudette Colvin, right? Claudette Colvin is the 15-year-old in Montgomery eight months before Rosa Parks who refuses to give up her seat on the bus and is arrested. Montgomery’s Black community for a time organizes with her around her case, but ultimately decides not to push forward with a boycott or a legal case. That’s the way we’ve now started to tell Colvin’s story. And Colvin, I think, is increasingly part of how we tell the story of Montgomery. Except we actually miss the second half of her story, which is that Rosa Parks makes her stand and they decide to pursue a legal case. In Rosa Parks’ case, she decides to, but this is a state case.

One of the things they learned years before with a case by another woman by the name of Viola White is that the state would often tie up these cases in state court and not let them go up on appeal. So the lawyer for Rosa Parks, a young 25-year-old named Fred Gray decides what we’re going to do, we’re going to file a case directly into federal court to try to get around this tactic of the state. He wanted plaintiffs for that case and he wanted a minister on that case. No ministers were willing to be on this case that Fred Gray is going to file in federal court. But, four women are on that case. The title woman is 38-year-old midwife by the name of Aurelia Browder. There’s an older woman on it and there are two teenagers on the case, Claudette Colvin and Mary Louise Smith. So, four women on that federal case, [they had] no men and no ministers, [because] they didn’t want to be associated with it. It was too scary. But two teenagers. I think we don’t always tell the full story of Colvin and the courage she summons that second time to be willing to be on that federal case. And it is that federal case that goes all the way to the Supreme Court and leads to the desegregation of Montgomery’s buses. So, I think again we miss, even in these moments that we think we know, we miss the role of young people.

You mentioned Birmingham, right? What actually galvanized John F. Kennedy’s attention and gets the federal government to act in the spring of 1963 is that young people start to join the downtown protests and are getting arrested day after day after day. And it’s controversial. People are very critical of King and of the SCLC for letting young people be part of it. They’re arrested in huge numbers. But, in many ways it is those young people — because there weren’t enough adults willing to do that — that really take the movement and Birmingham forward in 1963.

Hagopian: That is so inspiring to know. I feel like just being reminded of these stories makes me want to redouble my efforts when schools reopen and make sure that my students learn all of these stories. I thought maybe I could squeeze one more question in before the final question, just about the role of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, because I think it often also gets left out or briefly mentioned in textbooks as one of the players in the Civil Rights Movement. Yet so much of the Civil Rights Movement was organized by young people in the organization, right?

Theoharis: A couple of things about SNCC. So, SNCC was really started, again, by teenagers and by college students in February of 1964. College freshmen in Greensboro, North Carolina decide that they’re tired of the ways that Black people can shop at downtown stores, but they’re not served equally. They can’t go to the lunch counter, but the stores are willing to take their money. They’re also tired of people talking about how it’s an injustice but not acting. They’re fed up with the older generation for not really being willing to confront [racism; the system] head on. So these four friends go down to the Woolworths, ask to be seated, and before they do so they buy some school supplies because they want to demonstrate that they’re willing to take their money but not let them eat at the counter. Then they ask to be served and they basically say they’re not going to leave until they are served.

And Woolworths is like, “Oh, they’ll just go away.” That first day they just kind of ignored them. Then they go back and word of their protests has reached campus, they go to North Carolina A&T. The next day those four are joined by 23 others, including young women students at a Black women’s college in Greensboro named Bennett College. So four becomes 27, and the next day it’s 63. By the next day they’re overflowing, well versed in their craft. By the next week there are students now not just in Greensboro, but in Raleigh and Durham. And these students spread across many, many cities and towns. It is these young people, these college teenagers in their early 20s who then come together in April 1960, to work to form SNCC, or the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. And Ella Baker plays a huge role there, too. Even though she uses money from the SCLC to get the meeting started, she doesn’t want the young people to be subsumed in these other organizations.

Hagopian: Didn’t she actually have to argue with Martin Luther King that SNCC should be a separate organization?

Theoharis: Yeah, because I think she was worried, for good reason, that their energy and their vision would be constrained if they became just a youth branch of the SCLC or the NAACP. SNCC will really push the struggle forward, particularly around voting rights, around building freedom schools, around really cultivating local leadership in many places across the deep South. But, it’s the work, again, of 18, 19, [and] 20 year olds. I think sometimes when SNCC becomes part of the narrative of how we tell the Civil Rights Movement, we forget that these are actually 18, 19, [and] 20 year olds.

Hagopian: What incredible courage and political vision and leadership that SNCC played in the Civil Rights Movement. Thank you for sharing that. It also just made me think that yes, I think teenagers were some of the the backbone of the Civil Rights Movement, but you even have examples, like Ruby Bridges, of very young people playing an important role in the movement. Ruby Bridges came to Seattle just a few years ago to give a speech at one of the local schools, John Muir Elementary School, and she inspired them to launch Black Lives Matter at School, which now is a national movement. So, maybe you could just say a word about Ruby, and then I’ll ask my last question?

Theoharis: Well, again, when we think about school — and again, most schools refuse to desegregate — but again, if we think about the halting wave of school desegregation, that happens both in the 1950s and increasingly in the 1960s. That’s tiny, tiny people going into situations — whether Ruby Bridges, whether it’s what happens in Little Rock — and people have written about how many of those young people were actually young women.

Hagopian: Okay, cool. Well, I want to ask a question that gets at our reality today. I think, and you point this out in your book a lot, that young Black Lives Matter activists today are often chastised for not following the blueprint of the Civil Rights Movement and being too strident in their criticism of police brutality. As you write in A More Beautiful and Terrible History, “CNN’s Wolf Blitzer criticized protests in Baltimore as not being in quote ‘in the tradition of Martin Luther King’, and Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed invoked the history of King to celebrate Atlanta’s tradition of free speech, but then admonished protesters, [saying] ‘Dr. King would never take the freeway’.” Maybe you could tell us about some of the militant protests that students actually did lead in this era, junior high and high school walkouts and protests in the late 1960s and 1970s, from LA to Boston. What were their demands? I was really amazed by how similar demands are around police on campus, curriculum, more Black teachers, that kind of thing.

Theoharis: I also think that those criticisms of Black Lives Matter really get Dr. King wrong. Over and over, Dr. King is saying disruption is necessary. Over and over Dr. King is talking about police brutality. Over and over Dr. King is criticizing the role of liberals and moderates in saying they’re with the movement. So, I think that gets Dr. King wrong. I think there’s a way we tend to look back on the Civil Rights Movement like it’s sepia toned; it sort of seems like all the decent people were with it. And this really is not right. Most Americans during the Civil Rights Movement did not approve of the Civil Rights Movement, and that’s not just a product of the South.

For instance, in 1964, The New York Times surveyed New Yorkers and a majority of New Yorkers think the Civil Rights Movement has gone too far. Well, in 1964, the year before the Voting Rights Act, and one of the things that these New Yorkers are reacting to is a growing movement in New York City around school equity and school desegregation. That had culminated on February 3, 1964, with a massive school boycott. Almost half a million students and teachers stay out of New York City public schools to protest a lack, or even a plan for, comprehensive desegregation in the city.

Part of what’s happening in New York City at this point is the city schools are segregated. They’re growing more segregated, again, because this is a period where more and more African Americans and Puerto Ricans are moving to New York City. Schools in Black and Latino neighborhoods are growing more and more overcrowded. One of the board of education’s suggestions in the early 1960s is not to even out schools by desegregating them, but to move Black and Latino schools to double session days. Basically, some kids go during the first half of the day, and some kids go to the second half of the day. So, you have a growing movement in the city of parents, young people, and some teachers that culminates in what is the largest protest of the 1960s. We typically think of the March on Washington, but actually the numbers of the school boycott in New York City were almost twice as many.

And we’re going to see these kinds of school walkouts and school boycotts again throughout the late 1960s, particularly as high school students, as you mentioned in LA, in Boston, in New York, in many cities, walk out of schools protesting overcrowding, protesting things like inadequate bathrooms, protesting the lack of Black and Latino history in the curriculum, protesting the lack of Black and Latino faculty, protesting police on campus. There’s a huge wave of school walkouts in the late 1960s by both Black and Latino students, and I think there’s a lot more work to be done in terms of talking about the interconnections between African American and Latino history in that period.

[breakout rooms]

Hagopian: I’m excited to hear from a couple of young activists that we have with us here today. I’m going to start by turning it over to Jeanne to introduce our first student activist.

Theoharis: I live in Brooklyn, so one of the movements that I’ve been really inspired by here in New York City is a movement of young people called Teens Take Charge. In many ways, Teens Take Charge is carrying on some of the work we’re just talking about in terms of the struggle for desegregation and school equity here in New York City. Sometimes I ask my students, “When did New York City schools desegregate?” It’s a trick question because, of course, they didn’t. So, I wanted to welcome Karma Selsey to introduce herself and also to introduce some of the work that Teens Take Charge is doing here in New York City.

Karma Selsey: I’m Karma and I’m a senior at New York City Lab School and an incoming freshman at Brown University. For those of you who don’t know, Teens Take Charge is essentially a youth-led educational equity organization. We started in 2017 and our origins were actually student testimony, which is basically just students sharing about their experiences living in a segregated school system in the modern day when the narrative is generally that segregation is completely over. But, we also engage in direct action, and that can look like anything from a small meeting with a few representatives and people from the DoE [Department of Education] or a large protest.

Last year, on June 6, we had a rally on the steps of the DoE’s office, right across from City Hall. Right now, obviously, we’re not able to organize protests like that, but what’s been happening recently is the Summer Youth Employment Program, which is basically a New York City based program where about 75,000 students every summer, based on a lottery, get the chance to engage with paid internships or jobs over the summer. That program has been canceled and Mayor de Blasio stated public health and safety concerns, even though it’s clear that that’s not really the full truth because a lot of CEOs and organizations that normally hold positions for SYEP were more than ready to offer remote and virtual enrichment opportunities via SYEP, and they can’t do that without the program. So, we recently started a petition to urge de Blasio to take action and to rethink what he’s doing. He talks a lot about injustice and he claims to be a very progressive person, but when it comes to actually changing the system and not just trying to save face he usually doesn’t step up.

Based a call on with WNYC with speaker Cory Johnson, our representative from TTC helped convince some members of the city council to be on board with this, help urge de Blasio to reinstate SYEP, and allow for enrichment opportunities over the summer so that we don’t actually have a public health and safety concern where a bunch of young people are just outside over the summer and they don’t have anything to do. There are statistics that we know SYEP decreases violence, so if you’re really worried about public health and safety then you would be worried about these things, as opposed to just allowing them to continue.

Hagopian: Excellent work, Karma. We wish you all the best in your struggles and we’re looking forward to hearing about a victory out there soon. I want to now introduce Jaden Thomas, who was a senior at Franklin High School here in Seattle, where we live. He’s been a member of the NAACP Youth Council for the past couple of years and he has served as one of the council’s vice presidents for the past year. Jaden uses his voice as an advocate for students and families, and I’ve seen that myself. The Black Lives Matter at School movement, he’s been a participant in. I saw his brilliant dance troupe perform at our Young, Gifted and Black talent showcase to wrap up the Black Lives Matter at School week. He’s also been a leader in the fight for ethnic studies that he’s going to talk to you all more about now. So Jaden, welcome.

Jaden Thomas: Good afternoon, everybody. Yes, as Jesse mentioned, I am a part of the NAACP Youth Council here in Seattle, Washington. First of all, we call it NYC, which can be confusing because we have people from New York here. But, in the NYC we have a list of demands, and one of our demands is to fight for ethnic studies. Ever since I joined the Council about two years ago that’s been one of our main focuses, fighting for ethnic studies to be taught in classes and at all grade levels. In the Seattle Public School District ethnic studies at one point was offered as an elective class, but we wanted it to be mandated so everybody has to take it at all times. And throughout, they learned about it from kindergarten through 12th grade. A lot of people don’t get it until they’re in high school. Then, sadly, the program was cut; the person who was fighting to keep it in the schools and was building up the curriculum, it was cut for reasons beyond their control. So, at this point we’re still fighting to get the budget built back into Seattle Public Schools for it to be made available for all students.

As I said in the small group discussions, history just really repeats itself. The conversations that we’re having right now are conversations that my grandparents were fighting for and my parents were fighting for. Now, me being 18, we’re still fighting for the same things. We’ve come so far, but we really have a far way to go for it to be equal or to be an ideal situation that we want. So, like I said, in our list of demands with ethnic studies, a couple others in the council are still working on trying to build a curriculum, as well. We have representatives who helped build the curriculum for all the courses and, like I said, for each specific grade level we have people that have gone into the schools, to some kindergarten classrooms, and then we have a few people that have taught some ethnic study lessons at their Sunday school, because we had people that worked for Sunday schools. That’s really our fight at the moment. That’s one of our fights. We have a lot of other demands that we’re working on to just build up a voice for the youth in Seattle Public Schools, and also in our schools because we want to see equity for all the children. So, thank you.

Hagopian: Right on. Thank you so much, Jaden, for sharing that. People should really know that the NAACP Youth Council was one of the main driving forces that actually got the Seattle school district to form an ethnic studies department and to demand that every child have the right to learn about the ethnic and cultural diversity that makes up the Seattle schools. You all have been an inspiration to me, so keep up your struggle.

Jeanne, I was hoping you could talk to the group more about Diane Nash, how the Freedom Rides got started, and the role of young people in seeing those through?

Theoharis: Just so we know where we’re at, our timeline is the students didn’t start in the winter, but the first meeting of SNCC happened in April 1960. Then they have a second meeting, and then in 1961, a group, Congress of Racial Equality [CORE] decides to organize the Freedom Rides. The idea behind the Freedom Rides is that the Supreme Court has made two different decisions, one saying that interstate bus travel must be desegregated — and that’s actually a decision they made in the 1940s — but then they’d also made a second decision the previous year that interstate bus terminals that serve interstate buses also had to be desegregated.

So, what CORE decides they’re going to do is they’re going to organize a Freedom Ride to try to force the federal government to enforce its own laws, because, in fact, even though the Supreme Court had ruled this, in parts of the United States it wasn’t being upheld. So, the idea behind the Freedom Rides is that they would basically get on the bus in D.C. and they ride all the way down through the South and end up in, originally, in New Orleans. Although that’s not where they end up, ultimately. They would test both the bus itself and also the bus terminals. So they head out and it’s an interracial group, 13 people, both black and white, and they’re doing okay until they get to Alabama. They’re riding on two different buses. One’s a Troy and one’s a Greyhound and they encounter massive violence. One bus in Anniston, Alabama is firebombed and then the second bus, in Birmingham the Klan attacks it. The police know what’s going to happen and they give the Klan 15 minutes to attack. And the FBI knows this is going to happen and they stand by. There’s this massive violence and the Freedom Riders get very hurt. Nobody gets killed, but they get very hurt. And CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, decides that this violence is even worse than they had expected, sso they need to suspend the rides. And SNCC, particularly Diane Nash — who was a young woman who had grown up in Chicago but was attending Fisk University in Nashville — decides that can’t happen, that basically to suspend the Freedom Rides and the young people on the Freedom Rides would be to let violence win. SNCC young people were very worried that the message would go out to white segregationists that all it would take is violence, that you would see this uptick in violence but also that there was this sense that the movement could be defeated.

So these young people, in the midst of this incredible violence, are like, “We’re going to continue this.” And Diane Nash drives the Kennedy’s crazy because they see this as a problem. They see this as getting in the way of their foreign policy. They think it’s making the United States look bad. They think the Freedom Riders are making the United States look bad, but SNCC is undeterred. They basically send young people down to pick up the rides again in Alabama, and they encounter massive violence again in Montgomery — massive violence, people sustained permanent injuries, both white and Black people who joined the SNCC part of the ride, and yet they kept going and they basically forced Kennedy’s hand. Many of us may have heard of the Freedom Rides, but I think the ways that young people basically play this decisive role in saying we can’t let violence win and going when older people had been like, “No, no, maybe this is too much” I think is not always the way we tell that story.

Hagopian: Thank you. We were getting a few questions that I wanted to try to get to in our remaining time. One question that came in said they would love to hear Dr. Theoharis contextualize these two eras in terms of a timeline. Are we collectively expecting the youth to move too fast and accomplish too much in too short of a time period?

Theoharis: We haven’t talked that much, but I don’t want to miss the role that, because we’ve spent a lot of time talking about southern young people. Certainly one of the things that happens in the later 1960s, we talked a little bit about 1964 in New York City, but in the later 1960s, you have student walkouts happening in many, many northern cities and many western cities. Again, these walkouts in some ways are picking up where parents and community members in many of these cities had been struggling. For instance, in Boston around issues of school equity for more than a decade at this point. Then young people step in and are like, “We’re going to take the struggle into the high schools and we’re going to start walking out.” So you see all these walkouts in 1968, 1969, and 1970, protesting many things that are unfortunately still with us — lack of ethnic studies in the curriculum, not enough diverse teachers, non working bathrooms, not good facilities, science or music are not as good as some other kids are getting.

I think we see this activism come back in terms of student walkouts every couple of decades, where we see young people having to pick up the same fight. I think we’re in another moment of this, where we see the same conditions on unequal resources. The other thing that I think we see today that we also saw in the 1950s and 1960s in northern and western cities, they didn’t want to be seen as segregationist. They didn’t want to be seen as racists. So, how they often justified their unequal schools was by what I and many scholars called “culture of poverty,” this idea that Black and Latino families and communities had developed dysfunctional behaviors or values that got in the way of school success. So the reason that Black students or Puerto Rican students were struggling in school was because their communities didn’t properly value education, or they didn’t have the right values for success. These kinds of arguments come back, like we see all the time today, to justify the kind of inequality we see in schools today.

One of the things that I think is really useful about studying these movements of the late 1960s and these young people’s walkouts is that they’re pushing back explicitly on this idea that we don’t value school, we don’t have the right values for success, and forcing the issue. Because one of the things that you’re going to see school officials, again in LA and Boston and New York, basically saying is, “We don’t have inferior schools, we have inferior students.” Using this language around problem kids. Again, it’s a language that I think we see today. There’s this whole myth that Black students don’t value education the way other students do. But, it’s a myth that is used to justify the unequal resources and unequal access to college prep.

Again, one of the things they’re fighting for in the school walkouts in the late 1960s is also access to college classes; [there] not enough. We see that in struggles today and I think certainly we can’t expect high school students to have to bear the brunt of this activism. I think what we have to do is imagine movements where high school and college students are leading but also where parents, teachers, and community members are leading, because again, this cannot fall on the backs and shoulders of young people.

Hagopian: Thank you. Thank you so much. There are a couple questions for our student activists I’d like to get to. Mason said, “I’d love to ask Jaden and Karma what or who inspired them to be so engaged at a young age, and if they’ve encountered obstacles or resistance, specific to their age?” Then Katie asked Jaden and Karma, “How can adults help nonpolitical students get involved in activism, not just signing an online petition? How can we inspire them to go somewhere and take action?” So Karma and then Jaden, are you interested in answering those questions?

Selsey: For the first question about how I got involved with this work. I think for me it really starts back when I was really young and when I realized that systemic injustice was a thing and that my race and gender matter to people in ways that they really shouldn’t. Right before I turned 10, a couple weeks before I turned 10, Trayvon Martin died. I went to a predominantly Black elementary school and the next day, or whenever the next time we had school was, we all just collectively decided to wear Black hoodies in solidarity with each other. That was when I realized something’s wrong with our country, with the world, and the way that we interact with each other. Once I got to middle school and mainly high school I had a lot more opportunities for activism. I figured now that I’m older and I have more independence I owe it to myself and to my community to do whatever I can. In junior year I came across Teens Take Charge and I found out that they were doing their rally on the steps of Tweed Courthouse. That was just kind of it for me and I’ve been really involved ever since.

I also do some work in the climate justice movement. I’m not as heavily involved in that, but overall I just think that it was really that moment when I was almost 10 that just made all the lessons that my parents have taught me about how I have to act differently, and how I have to always comply with the police, with authority. That’s when it all clicked for me.

Then for the second question, I think it’s really just about making people understand why certain issues either affect them or affect people that they know, because I think that it’s really difficult for people to get involved with certain movements if they don’t have some personal stake in it. It’s not necessarily about using all of this really fancy jargon, like complicated definitions of things. For example, if I were to explain the ways that school segregation affects people that I go to school with, I’m in a colocated building and the school below me has none of the resources that my predominantly white school has. So, something as easy as that I could make somebody realize, “Oh, this is unfair.”

Hagopian: That’s brilliant, and I love the way you described your intersectional approach to understanding how racism and sexism overlap and then taking up other issues like climate change and how all these issues are interwoven. Thank you for sharing that.

So, there’s a question about ethnic studies that I think is worth us thinking about. Somebody said, “I’m interested in teaching all classes with an ethnic studies lens versus teaching an actual class called Ethnic Studies. Which approach would be better in the long run?” Maybe I’ll say a quick word about that, as somebody who has done both, and then Jeanne, if you have any perspective on that, too, let me know.

I think that both are valuable, and that we should struggle for both. I think that we need to fight to integrate ethnic studies approaches into all of the existing courses because right now the standard American history courses are mostly Eurocentric history courses. They mostly teach a white people’s history. I think part of the struggle in Seattle that’s been so brilliant is to say, “We want ethnic studies in K through 12, and we also want it integrated into the current curriculum.” There’s been some incredible mostly women of color who have really led that struggle here in Seattle, like Tracy Castro-Gill, who led this struggle and then became the director before she was forced out for her advocacy. People like Rita Green from the NAACP, and many others wanted this to be integrated into the current classes. I think that’s such a powerful message, to say there’s something wrong with the way all of our classes are being taught and we want to change that. I think that’s very valuable.

At the same time, I’ve also taught an ethnic studies class that’s a standalone course. I think some of the power of having a standalone course is that the students who are in it know that they are in a course that’s part of a tradition that started with young people. Young college students in 1968 and 1969, in Berkeley and at San Francisco State lead the longest student strikes in U.S. history and shut the campuses down demanding that they get to learn about their own histories that have been forced out and getting to walk into a class called Ethnic Studies and learn that it was young people that fought to get that class. I’ve found it brings a new attention and urgency for students in that course. I think that there’s value in having that course at the same time we fight to integrate the ethnic studies approach into the existing courses.

Theoharis: Just to pick up on that in a couple of different ways. Part of what we are trying to do, even in this little mini course, is to show that even if there’s not space — and here I’m talking more to educators, although students, I think, would agree that — even if you have to teach a particular curriculum with a particular textbook, there are different ways to teach the stories that are in there. I think sometimes we want to have an ethnic studies class or we want to have an ethnic studies curriculum, and then the political forces where we are make that impossible. In some sense, we get a bit paralyzed. So I think part of why we were doing this little mini course today is that some of the stories that are in the books, whether it’s Rosa Parks, whether it’s Brown v. Board, whether it’s what King did in Birmingham, are stories that we can teach differently, talk about differently, understand the lessons differently. But like Jesse said, I was an African American Studies major in college and the class I’m teaching at Brooklyn College is a class on the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. It’s not American history, it’s expressly just focused on this time period. And I think ethnic studies perspectives need to be all over the curriculum. That’s not the only way we do it, and to have African American Studies classes where we’re just studying the Civil Rights and Black Power movements are so amazing and valuable, too. I think we can want both and struggle for both. But again, at base even the political forces where you live make both of those impossible. That doesn’t mean that we have to put up with the stories that we’re given. I guess I would want us to understand that no matter what, we have access and we can do differently.

Hagopian: Right on. Well, Jeanne, do you have any last thoughts about why this history is important for us today and where we go forward with this?

Theoharis: My last thing would be, I guess, where we started. [There are] two points that I just wanted to finish with. The first is: What does it mean to center and to see young people in so many parts of the Civil Rights Movement, even that we know young people are in the vanguard, and they are in the vanguard at moments and in ways that are making adults in their community, Black and white adults, very uncomfortable. I think we need to understand that and reckon with it. My book is called A More Beautiful and Terrible History, [which is] a James Baldwin quote where he’s talking about American history. Baldwin writes, “American history is longer, larger, and more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything that anyone’s ever said about it.” It’s a beautiful quote. I think it gets to how we often sand off the edges of the history we tell. I think we don’t talk about the way that young people lead and we don’t talk about the ways that they were often opposed. So, when we get into the present — and here we are in the midst of new movements, where some of you and adults in our communities are nervous about those movements — we can put that in historical perspective and say, “That’s been true all along, that movements are not necessarily embraced in the moment that they are in.” To carry that with us, that your righteousness is not necessarily going to be recognized in the moment, and I think that’s a really important lesson. I think oftentimes, because of the way history is told, it’s very demoralizing because struggle is so hard and because the way that we’re taught is that somehow Rosa Parks sits down and everybody realizes there’s an injustice, we band together, and we forget that that’s in fact not exactly how it worked. So I guess that’s where I would want to leave us, that the picture we’ve been given of the Civil Rights Movement, it was much harder than we’ve been given. And the young people really led the way in many, many of the places that we are now most proud of today.

Hagopian: Absolutely. Thank you so much for sharing those lessons. For me, I just feel like they’re much sharper in my own mind. I’m going to be more effective in my instruction this year and I hope the same for many educators here.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Breakout Session Discussions

During the breakout sessions, participants highlighted a number of questions, including:

Is there a map somewhere of youth school boycotts or walkouts? Kind of like the Indigenous peoples day map on the Zinn Ed Project site? [At ZEP we don’t know of one, but it would make a great student National History Day project.]

We talked about things we taught/learned in our classroom, but also the importance of students being directly involved in organizing/activism (not just reading about it). Some key questions from our breakout group: How can teachers make sure students feel empowered day to day? What are teachers doing to do that right now? What would it look like for students to lead a movement now in this moment especially around equity in education?

How do the youth know where to start? How does one start organizing?

How do young people stay involved during social distancing?

Reflections and Lessons Learned

Participants shared what they learned and appreciated about the session in their closing evaluation. Here are some examples:

I had no idea how much of an impact youth have had on the Civil Rights Movement. It was shocking since at school we only focus on big figures like Martin Luther King Jr.

Leaving the contributions of young people out of the narrative of history helps reinforce the idea that the youth of today are powerless against the injustices they experience and observe in the world.

I love all of the examples — both historical and contemporary — that were given to tell the story of how young people are leaders. It is also a very good reminder that teaching a full story is always better than teaching a moment.

I need to look for youth activists in the struggles I already cover. After hearing this, I’m sure that they are there. Then I need to pull those struggles through to today, even if briefly.

The most important thing I took away was actually knowing that there are so many other educators working towards the same goal with what resources we have!

This highlighted the need to make sure I am including ways for students to feel empowered even within my own classroom. It makes me want to push my own practice further and make sure students can have the space to advocate for themselves daily rather than at the end of the semester. Therefore, they know they can have their voices heard and they do have power.

It was so helpful to be reminded that struggle is a struggle and that young people have so often been leaders of change. Would be great to talk more with folks about how grown-ups can both support and get out of the way.

Two things: The first is Dr. Theoharris’ point that many adults were in fact NOT on board with student activism or their methods during the Civil Rights era, and that despite this, students and young people organized and worked for change. This makes me really re-think how educators and adults guide/support youth activism today. The second takeaway was the way that CORE and SNCC had to collaborate to make the freedom rides successful — that adults would start out this project, but when faced with incredible violence, students would pick up the baton despite the known dangers is such a powerful story. Also, Jesse Hagopian facilitated the conversation masterfully, and I LOVED hearing from not just Jeanne Theoharris, but also Karma and Jaedon. Seamless transition from whole group to/from breakouts. Fantastic online session!

I think it worked really, really well. The balance of this critical history and hearing the voices of youth in the struggle today was perfect. Dr. Theoharris and Mr. Hagopian do such an amazing job of making history come alive and help us see how to share these important stories with our students. I also appreciated the opportunity to connect in the breakout, especially as I was lucky enough to be placed in a breakout with three young people and learn from them. (Shout out to Miles, Jessica, and Quinn!)

One of the most interesting things that I learned about today was how Northern and Western cities fed into the myth that Black and Latino students were inferior in school. They used this myth to perpetuate the inequities that existed between minority schools and white schools.

The entire conversation was a great reminder to include young people’s actions as part of the CRM and not as something separate or only briefly touched on. Their history is our history and should be included in the movement at large not as a side note.

One important thing I learned today was how voices of youth have been historically silenced, even within the activist community. However, these same youth have ignored this critique and brought about meaningful change anyways. I plan to share this idea and the example of youth activism with my middle school students over the course of the next two weeks. I will do this as a way to provide historical examples of youth activism as they begin choosing independent projects to work on in our PBL classroom. This is exactly what I needed and the timing could not have been more relevant. I look forward to the next mini-course!

I loved the breakout sessions, it was a great way to require connections in a time when we are craving them. I liked the author’s speaking session in the beginning which provided a good overview and enriched the later sessions. My favorite part was hearing from today’s youth, both in the panel and breakout sessions. I didn’t expect to see students in the chat and it was a great surprise! I will recommend that my students join the next mini-class.

This was an incredible session. It was informative and invigorating. I am looking forward to many more. Thank you for making this accessible.

I appreciate you all! Thank you for doing such important work! I hope that even after physical distancing is over, you will still offer these opportunities. It was really great to be in a breakout group with people with such different experiences and from all over the world.

Resources

Here are some of the resources shared by the presenters and also by participants in the chat box.

|

The Girl from the Tar Paper School: Barbara Rose Johns and the Advent of the Civil Rights Movement by Teri Kanefield. Illustrated book about teenager Barbara Rose Johns, who led a student walk out to protest substandard conditions at a Virginia high school in 1951. |

|

Mighty Times: The Children’s March This student friendly documentary from Teaching Tolerance tells the story of how the young people of Birmingham braved arrest, fire hoses, and police dogs in 1963 to end segregation. |

|

A compilation of stories by Teaching for Change of young activists from throughout U.S. history. |

|

An online collection of historical materials, profiles, a timeline, a map, and stories on SNCC’s voting rights organizing. Many of the profiles feature stories about teen activists. |

|

Renee Gokey from the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) participated in the session and shared a story in the chat box of a young Native American activist who challenged school segregation before Brown v. Board. She was Alice Piper (June 7, 1908 – August 22, 1985), a Paiute (Nüümü) girl residing in Big Pine, California, who petitioned to attend the newly built Big Pine High School in 1923 and was denied entry due to her race. At that time, California educational law prohibited Native American children from attending a public school if a separate government run Indian school was established within three miles of the public school. Piper, along with six other Indian children, sued the district for the right to attend. [Renee Gokey also shared the key resource, Native Knowledge 360. Another child who, along with her family, challenged school segregation is Syliva Mendez.] |

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn