Did you know that the biggest civil rights demonstration of the 1960s

happened in New York City?

Did you know that at the same time people were pressing for desegregation in Montgomery and Birmingham, they were doing so in Los Angeles, Milwaukee, and Boston?

Participants learned about these stories and more in our Zinn Education Project People’s Historians Online mini-class on the Civil Rights Movement in the North on April 17.

This was the third in our series on the Black Freedom Struggle: From Reconstruction to the Civil Rights Movement. Author Jeanne Theoharis provided the history lesson, in conversation with Rethinking Schools editor Jesse Hagopian.

About 120 teachers, union activists, and students joined the class from around the United States. The chat box buzzed with conversations and questions about the hidden history of the Civil Rights Movement in their respective communities, including Milwaukee, Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Chicago, and New York.

Highlights

One participant wrote,

This completely changed how I think about the Civil Rights Movement. I grew up in New York, went to college in New York, and now teach in New York, and until I read today’s texts and listened to the discussion, I didn’t know about the New York City boycott or others.

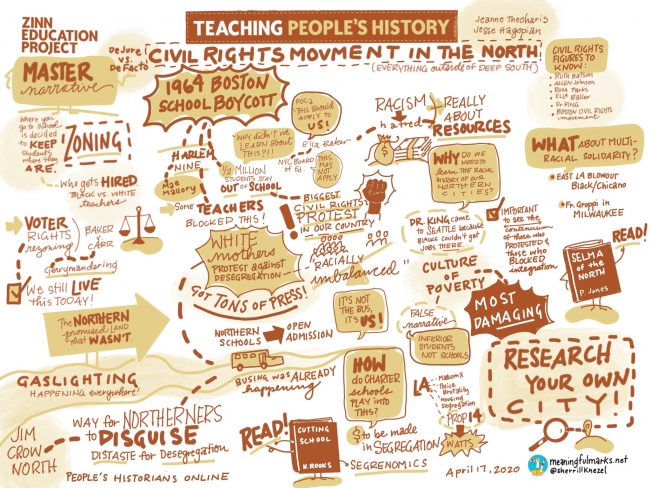

Another participant, Sherrill Knezel, turned her notes into a beautiful graphic summary of the session.

Participants shared more insights and teaching ideas from the session.

Many things stood out to me! One quote that I appreciated from early on was “God doesn’t draw those lines, they are created by government officials. They can be redrawn.” And the many systems that are created (and therefore possible to recreate) connecting education and political systems.

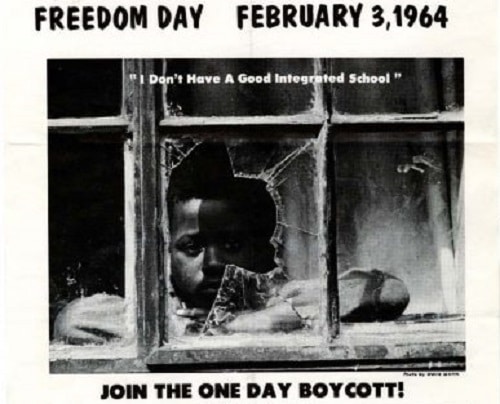

Before this series, I did not know that the largest civil rights protest in U.S. history was in 1964 related to school segregation and education equity issues! I always thought it was the Great March on Washington. . . I will find out more and teach this in the future.

There was so much good content, but one specific activity that I thought of based on Theoharis’s talk was having students look at side-by-side comparisons of articles from the same journalist covering the Civil Rights Movement in the South vs. in the journalist’s home town.

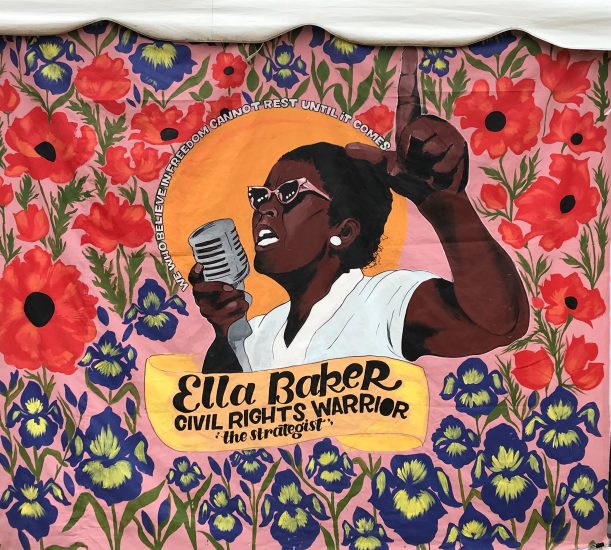

I hadn’t known much about Ella Baker and the 1964 New York City protest. Now I am looking forward to how I can incorporate it. I help with the teacher materials for the Minnesota National History Day, including identifying topics students can consider for each year’s theme. I am DEFINITELY going to get that in there.

Jesse Hagopian wrapped up the session with an invitation to research the Civil Rights Movement in participants’ own cities. Based on the enthusiastic response, we expect that will happen. To begin that research, participants can draw on many of the resources shared during the session, including those listed below.

Audio

Listen to the recording of the session on these additional platforms.

Resources

|

|

BooksThe Strange Careers of the Jim Crow North: Segregation and Struggle Outside of the South edited by Brian Purnell and Jeanne Theoharis with Komozi Woodard The Selma of the North Civil Rights: Insurgency in Milwaukee by Patrick D. Jones |

|

|

Cutting School: The Segrenomics of American Education by Noliwe Rooks Reds at the Blackboard: Communism, Civil Rights, and the New York City Teachers Union by Clarence Taylor See also: Lessons from the Heartland: A Turbulent Half-Century of Public Education in an Iconic American City by Barbara Miner |

|

Lessons“Teaching the 1964 New York City School Boycott” by Adam Sanchez “How Red Lines Built White Wealth: A Lesson on Housing Segregation in the 20th Century” by Ursula Wolfe-Rocca |

|

|

Articles“Rethinking ‘Busing’ in Boston” by Matthew Delmont (Smithsonian Magazine, December 27, 2016) “What Happened to the Civil Rights Movement After 1965? Don’t Ask Your Textbook” by Adam Sanchez (Zinn Education Project, June, 14, 2016) |

|

|

Court Cases |

|

People and GroupsMae Mallory and the Harlem Nine Rosa Parks in the “Northern promised land, that wasn’t”

|

||

FilmsSegregated by Design An animated 18-minute documentary of how the federal, state and local governments unconstitutionally segregated every major U.S. metropolitan area through law and policy. Walkout The true story of the Chicano students of East L.A., who in 1968 staged several dramatic walkouts in their high schools to protest academic prejudice and dire school conditions. ’63 Boycott In 1963, 250,000 students boycotted the Chicago Public Schools to protest racial segregation. |

||

|

PodcastsSchool Colors A narrative podcast that focuses on the story of Ocean Hill-Brownsville in Brooklyn, where “Black and Puerto Rican parents tried to exercise power over their schools and they collided headfirst with the teachers’ union — leading to the longest teachers’ strike in U.S. history.” |

|

Video

Watch a full recording of the public portions of the session.

Transcript

Click below for the full transcript with resources mentioned in the discussion.

Transcript

Jesse Hagopian: I want to welcome Jeanne Theoharis. It’s great to be back with you today. We’re really excited to have you back here, Jeanne. Thanks for doing this with us today. We’ll jump right into the questions.. So, we’re talking about the Civil Rights Movement in the north, the one that often gets overlooked and hidden in the curriculum of the North.

Jeanne Theoharis: Right, we’re using the term the way activists at the time did, which means we’re talking about everything from the northeast to the West Coast. When we talk about the North, oftentimes the phrase “the North” is used as a way to separate the whole rest of the country from the South, which is where supposedly the race problem in this country occurred. So, we’re just talking about the North today. This is everything outside of the Deep South, basically.

Hagopian: Right. Thank you for that clarification. I think so much of what we learned in history class has told us that racism is confined to the South in our country. But, I want to read something that you wrote in your book, A More Beautiful and Terrible History — which I highly recommend everybody get, I think it’s one of the most important studies of the Civil Rights Movement that really just systematically goes through and debunks the master narratives that were mistaught in school about the Civil Rights Movement — you said, “Many scholars and journalists since the 1960s have clung to this false distinction between a Southern du jour segregation and the Northern de facto segregation, making Northern segregation more innocent and missing the various ways such segregation was supported and maintained through the law and political process.” So, could you talk more about the master narratives that we learned in America about how racism was a Southern problem?

Theoharis: I would be curious for people to use the chat to talk about if you ever learned in school the ways that segregation . . . So we have this idea of Jim Crow segregation, and when you say that phrase “Jim Crow segregation,” what supposedly you’re talking about is the legalized system of segregation in the South. And certainly, Jim Crow encompasses that. But what me and a number of scholars are now arguing is that we have to use that term — that idea of a legalized system of segregation — to understand also what’s happening outside of the South, and it works as the law in different kinds of ways.

It didn’t necessarily say Black students and white students have to go to different schools. But what it did say, what school you go to is based on what you were zoned, that phrase zoning, which basically is the Board of Ed or whatever educational body governs your school where you live, draws lines to say these students will go to this school and these students will go to that school. God doesn’t draw those lines; they’re not naturally made on the earth. They are made by public officials, and they can be redrawn.

One of the things that’s really interesting about the period we’re going to be talking about is you will see school districts like New York, LA, and Boston constantly redrawing those lines to keep the schools the way they are, to keep schools majority white, majority Black, majority Latino in some places. They’re constantly redrawing them. So, that’s one of the ways that we’re going to talk about segregation in the law, segregation and policy.

The first one we need to talk about is zoning. The second is how do they decide what teachers go where? How do they decide what resources go where? Again, it doesn’t come from on high, it doesn’t just fall down from the sky. Teachers are assigned by the Board of Ed, by the law if you will, and therefore some schools have lots of experienced teachers and some schools have lots of substitute teachers. This is another way that segregation is working through and in the law; who gets hired. If we’re talking about the north, actually, one of the big problems in terms of school segregation in the north is that Black and Latino teachers have a very, very difficult time getting hired. In fact, the numbers of Black and Latino teachers being hired in cities like New York or LA are much lower than the population. Even people with the qualifications are finding it hard to get hired today.

Hagopian: That’s a problem that was [ongoing] then and today as well, right?

Theoharis: If we’re going to talk about something like voting rights, if we think about the South, one of the issues of voting rights in this period is voter registration. We were talking about this a couple of weeks ago with Rosa Parks and how there were these barriers in terms of the tests that were given or poll taxes. The barriers in the North are not necessarily in the area of registration, they’re in the area of districting, of how your district is drawn. There’s that word gerrymandering, [which] means that districts are drawn in particular ways to favor particular groups of people. And very much the way districts were drawn was to weaken or make almost impossible Black people to elect people to represent their interests.

There’s this really pivotal court case in 1962 — which I’m sure none of us learned about; I didn’t learn about it until I was a professor — called Baker v. Carr in 1962. Basically the Supreme Court in 1962 says, in fact, that the voting districts have been drawn in a way to disadvantage Black voters, to disadvantage urban voters. They make many major northern cities have to redraw those districts. So that’s how we get a John Conyers; that’s how we get a Shirley Chisholm is that it comes out of that Baker v. Carr decision. But again, when we tend to learn about voting rights in school, it’s very much focused on the South.

Hagopian: Yeah, no doubt. I appreciate that. So often we only learn about segregation as a Southern phenomenon, yet we’re living segregation every day here in Seattle, right? I mean, we see it in our school buildings, we see it in the differences between the advanced classes and the gen ed classes. So even though segregation is an everyday part of our lives across this country, somehow they get away with teaching over and over again that this is confined to the South. I think the same way that they talk about segregation being a phenomenon only in the South, they also talk about the Civil Rights Movement being a phenomenon only in the South.

I think one of the basic narratives that I’ve learned about the Civil Rights Movement that I think is problematic is that the Southern Civil Rights Movement achieved the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act and it was only then that the Black Freedom Struggle moved North and turned into the Black Power movement. It’s the idea that there wasn’t a civil rights struggle by Black folks before the Black Power movement in the North and they weren’t simultaneously struggling during the Civil Rights Movement. So, I want to go more in depth to some of those specific struggles, but just generally talk about that framework and what’s wrong with it.

Theoharis: I think you’ve pinpointed it right, which is that there’s this idea that somehow Black people in the North were basically satisfied. It’s a narrative we often talk about that turns on this idea of the Great Migration and that the North is a promised land. Certainly people were leaving the South because of racism, because of racial terrorism, because they were wanting more opportunities for their kids and for themselves in terms of schools in particular. But what they find in the North — to use my favorite Rosa Parks phrase — is the Northern Promised Land that wasn’t, which means that some things are different, certainly, but the systems of segregation and housing and job discrimination and police brutality are relatively similar. Again, Parks would say she didn’t find too much difference.

In fact, in the post World War II period, what you’re seeing in many Northern cities from New York to Seattle is these cities are actually growing more segregated, because we have large scale migration of African Americans and Puerto Ricans in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. In terms of school segregation they keep redrawing these lines, so you have parents who are active civil rights activists, you have union members in the North pushing against this. But you have Northern white people very invested in saying “We’re not racist. It’s open and fair up here.” So there’s this kind of gaslighting constantly of the Civil Rights Movement in the North.

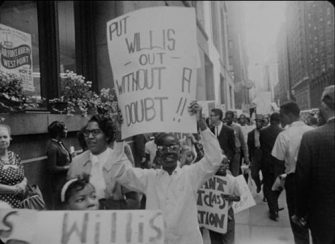

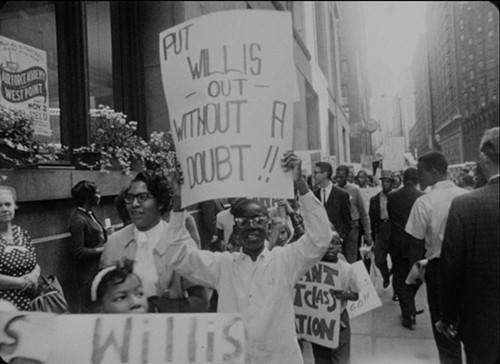

Hagopian: Absolutely. I want to get into some detail now about what those struggles looked like in the North, because they’re just fascinating and breathtaking. I feel so cheated that I never got to learn about these struggles. So, let’s begin with the epic 1964 school boycott in New York City. I mean, this is considered the largest civil rights protests in U.S. history and yet there’s so little that we get taught about it. There’s so little discourse in mainstream media and in society, it’s left out of textbooks, [and] there were very few remembrances of it when the anniversary came. So, why did most people not learn about this struggle in 1964 in New York, and what happened?

Theoharis: It’s a decade long struggle because once we have Brown v. Board of Ed, just like people in Montgomery celebrated, just like people in Atlanta celebrate it, you have Black people in New York City celebrating that decision saying this is going to apply to us. You have people in Boston celebrating that this is going to apply to us. You begin to see parents and civil rights leaders start to push to say this should apply to us. And the reaction in New York is not the same as what you see in many southern places. New York’s board of ed and New York’s superintendent, they’re celebrating the decision in a larger sense. But they keep saying, “Well, we just don’t know if it applies to us.” You begin to see civil rights activists like Ella Baker, we often associate Ella Baker with the South, but Ella Baker was actually running the Harlem NAACP in the mid-1950s. She’s very much like, “This should apply to us. We have segregation here, and we want to make this real here.” So, you began to see Ella Baker and a number of parents and activists organizing, trying to get the Board of Ed to change.

They had a big demonstration in 1957, at the beginning of school outside of City Hall. Again, New York’s response is like, “Well, we don’t think it applies to us, so (in what is a classic northern tactic) let’s form a committee to study it.” They decided to put two of their biggest critics on that committee, it’s actually called the commission, and that’s Ella Baker and Kenneth Clark, [who are] both on that commission. And that commission comes back and says, “Hey, you know what, there’s a lot of things wrong here. There are a lot of things you’re doing that need to change, including re-zoning, including teacher placement in the Board of Eds.” “Nah, nope.” And so they just ignore their own commission.

Then in 1958, you have nine mothers who keep their kids home in Harlem because they don’t want to send their kids to these under-resourced segregated schools. The mothers get brought up on charges. These are called the Harlem 9. If you don’t know that story, it’s an amazing story. Again, the Board of Ed finally decides, and this is another northern tactic, they’re like, “Okay, we’ll give your kids a different option. Not the million kids in the district, but your kids.” Then parents and activists keep pressing in the early 1960s and are getting nowhere. So finally in 1964, February 3, 1964, almost a half a million students and teachers stayed out of New York City public schools to protest the fact that we are a decade after Brown, a decade after the Supreme Court said segregation is unconstitutional, and we still need to have a plan for desegregation here. Not that we’re even doing it; we don’t even have a plan. And the powers that be in New York hate it, and the New York Times hates it. The New York Times calls it violent, they call it reckless, they call it irresponsible, and they call it violent. I think one of the things is also some of the people who helped to push the southern movement forward. I would say Northern journalists have a very different reaction and play a very different role when the struggles are closer to home.

Hagopian: I’m just fascinated by how many students took part in this struggle and the fact that teachers joined in with it.

Theoharis: I do not know what the union’s position was or how consolidated at that point, I don’t know. The board threatens to punish the teachers at first and then ultimately backs off. I’m not sure in 1964. I don’t know. There had been this whole radical teachers movement in New York City. Communists were one part of it, the TU. If people don’t know Clarence Taylor’s work, Reds at the Blackboard is amazing. There had been a strand of teacher organizing and activism that had allied with parents, but many, many teachers stood in the way in New York City. That’s a really hard story, I think, to have to tell. But, when you begin to see civil rights activists in the late 1950s pressing for changes in teacher placement, one of the big pushbacks is coming from certain teachers, not all teachers, absolutely, but certain teachers. But I’m not sure what the UFT did in terms of the school boycott.

Hagopian: I’m going to have to look that up and get some more details on that. I mean, the unity between students and teachers today, building the Black Lives Matter at School movement has been critical. It’s just really important to see precedent for what we’re doing all the way back to the 1930s, like you said in the TU. I mean, those stories are incredible to learn about how there were textbooks being taught to students in New York glorifying the Klu Klux Klan, saying they were a savior organization, and to see radical teachers joined together with some folks from the NAACP and others to make their own textbooks, to build struggles and protests, and then see that continuing — this kind of boycott is amazing. The biggest civil rights protest in our history was in New York in 1964. Education was a focal point of the civil rights struggle in the North. I wonder if you could talk more about the busing wars, especially in Boston?

Theoharis: Before we get to Boston we have this massive bus boycott in February, and white parents start to get nervous that the Board of Ed is going to respond to this. So, in March of 1964, about 15,000 white parents, mostly white mothers, marched over the Brooklyn Bridge to protest the board of ed’s floating of a modest school parents program pairing about a couple dozen schools to do a little bit of desegregation. These white parents don’t want anything to do with it, so they marched over the Brooklyn Bridge to protest their rights. They’re using civil rights tactics, but it’s basically [calling for] no desegregation. Interestingly, it gets massive media coverage and that media coverage is playing basically in the background as the U.S. Congress debates the Civil Rights Act.

So, one of the underbellies of the Civil Rights Act that again we don’t talk about very much is that the northern congressmen who are leading the fight to get the Civil Rights Act also realize they don’t want this coming back to their constituents. They end up putting this loophole. One of the things the Civil Rights Act is going to do is it’s going to tie federal funding for schools to desegregation. But they don’t want that to happen to their schools so they put this loophole in. Basically there’s a part of the Civil Rights Act that defines desegregation, but they put this loophole in basically assigning students to correct racial imbalance, because that’s how northerners talk about their schools. They’re racially imbalanced. So they put a loophole into the Civil Rights Act that is effectively preventing the passage of the Civil Rights Act.

Parents and activists in Chicago try to use the Civil Rights Act to challenge Chicago segregation. Basically, that loophole allows for the Chicago Board of Ed not to do anything. Similarly in Boston. Part of what’s happening, if we’re going to skip to the Boston story, is you have this longstanding — and I saw somebody write about this in the chat — we also have this longstanding movement in Boston. Similarly, people have been organizing before 1954, like one of my heroes, Ruth Batson. There again we get Brown and parents and activists in Boston are like, “Okay, we’re finally going to get some desegregation here.” They’re organizing all sorts of things. They’re organizing rallies, they’re organizing parent groups, they started to organize their own busing programs in the early 1960s, too.

One of the things Northern schools do is they start to pass these things called open admission. If you can get to this school, and if they happen to have a spot where you could go. They do this in Boston and a Black parent group basically forms this thing called Operation Exodus to pay for their own buses to get their kids to these schools. They think they’re going to shame the school committee into doing it and they don’t. But, I think one thing that reminds us of the busing is present — whether it’s in New York, whether it’s in Boston, whether it’s in LA — the bus is present in these cities long before busing, and it’s being used for a lot of things. But one of the things it’s being used for is to maintain segregated schools in a city like Boston.

So, the way that we tend to talk about busing in the late 1960s and 1970s, acquiesced to white parent discourses. They didn’t want to seem like they were like racist Mississippians and so they’re like, “We’re not against it; we’re not segregationists. We just don’t like busing.” Your kids are being bussed already, but you don’t see the media pressing that issue. So, in Boston 85% of kids are bussed before busing and yet that’s not the story we tell about Boston — that white parents in Boston, white political leaders in Boston, realize how useful this language of busing is by the early 1960s so you begin to see them talking about “We’re against busing. We’re against busing,” and they realize how useful this language is.

Hagopian: I think that points worth underscoring, that they were already busing their kids. So it wasn’t that they were against busing, it’s that they were against desegregation.

Theoharis: Right. As Julian Bond would say, “It’s not the bus, it’s us.”

I think we had a moment, as people may remember, last summer in one of the first Democratic Party debates, where we began to have maybe an inkling of we were going to have a real honest conversation about this and about what it meant for the fact that Biden’s national political career begins with siding with white parents against busing, what that really was about. We had a brief moment when we saw Kamala Harris challenge him and then obviously she folded on that issue. But I think to really talk honestly about what it meant to be anti-busing was about how Northerners wanted a more palatable way to disguise their vehement opposition to desegregation. I think that’s one thing we have to really reckon with is that opposition to school desegregation was as strong in the North as it was in the South. It didn’t necessarily take the same forms, but as I think somebody brought up in the chat, when UCLA put out that study of where are the most segregated school systems, the top one is New York.

Hagopian: And the schools in the north today are more segregated than in the south in general. I taught at an elementary school in D.C. when I first started, and it was a 100% Black school. Most schools are highly segregated still to this day. Nikole Hannah Jones writing about school segregation has been really important. Why is it so persistent and why is school segregation such a big part of the way institutional racism functions in the north?

Theoharis: Well, it gets to this question that I think sometimes we reduce racism to hatred. I think that’s an aspect of racism. But I think what grappling with this history of the North forces us to see is that it’s about resources. It’s about hoarding resources and feeling like you deserve what you have. I mean, school segregation is so prevalent precisely because it allows certain people to get more at the expense of everyone. But then to create a system where that somehow seems justified, because Americans are also very invested in “We’re all on an equal playing field.” That’s how we talk about our educational system is that education gives us all a chance. But, obviously what separation does is it gives some people a better chance.

One of the things you see in northern cities in this period, again, as you’d have this large-scale migration, is that schools educating Black and Latino students are getting more and more crowded in this period. Instead of being willing to change the zoning to make them less crowded, what you see is that that board of ed in New York or in LA, they start to say, “Okay, we should have double sessions. Some kids go to school in the morning, and some kids go to school in the afternoon.” And Black and Latino parents are organizing against this, but it shows how the fight to really fairly distribute these resources would have meant changing the advantages that some people were getting through this system.

Hagopian: Absolutely. You saw just how hard white folks were willing to fight to keep those advantages in Boston; watching some of the videos of the attacks on Black students on buses is just terrifying to see. The last question before we break out into rooms and talk, are there any civil rights leaders outside of the South that we should know more about, that people should look up and read more and study?

Theoharis: I started my career teaching at Jeremiah E. Burke High School in Dorchester, Boston. That’s where my interest in this history begins. If you don’t know Ruth Batson, Alan Jackson, and many of the leaders in Boston’s Civil Rights Movement, that would be the first place I would say to start. In fact, Boston figures into the way that the traditional narrative tells it, which is we have civil rights to Black Power. Then we have the Boston busing crisis, where white people get to play the main role, as opposed to a much more honest grappling, which is that you have a 25 year movement in Boston where they try everything.

In many ways, I think Ruth Batson has a little bit of that kind of Rosa Parks spirit of just trying different things over and over. You try organizing parents, you try having rallies, you try having sit-ins, you try having independent busing programs, and then you try a federal court case. I mean, in many ways what happens in Boston is that the federal court case is the last [attempt]; they’ve tried everything [else]. Then in 1972, the NAACP decided that they needed to go to court. But to start the story in 1972 misses both everything they’ve tried and how much resistance they have encountered.

I think to deal honestly with what happens in Boston is to understand how hard white people had fought not to desegregate. And it’s not just people in South Boston. I think there is a way that we tend to portray racism as kind of redneck, as kind of about working class people. And it wasn’t just working class white people in Boston that didn’t want desegregation. Middle class neighborhoods as well, both in 1974, were a part of the resistance to desegregation, but also have fought for years as well. So, the Civil Rights Movement in Boston.

I would also say, and Jesse and I are going to be talking more about this on May Day, but I also think we have to go back to the figures we think we know. I would say, obviously, Rosa Parks, but really learning about Ella Baker in New York City. But on May Day Jessie and I will be talking about Dr. King.

Turning to Dr. King, one of the things I’ve gotten really interested in is how much Dr. King is talking about Northern segregation in the 1950s and early 1960s, and how we completely ignore that whole side of Dr. King. Even as people have more recently gone back to really excavate the radical King, somehow the King that has been challenging Northern liberalism, really since they started the SCLC, he’s talking about Northern liberalism and the limits of it, but we don’t know that King.

Hagopian: I’m really excited for that conversation. A point that you made to me earlier just about how when we can relegate racism to the South that can make white liberals in the North feel like they’re off the hook for any other problems. I think reclaiming this history of the Northern Civil Rights Movement is just so powerful and reframes all of American history.

[breakout rooms]

I want to start with a question about the stakes of this conversation and why it’s important that we have this conversation about the Civil Rights Movement in the North. But, if other people have questions please throw them out in the chat and we’ll try to get to them in the next few minutes.

I want to talk about why we need to learn the histories of struggle in our own cities in the North and what happens if you’re robbed of the story of the struggle for racial justice in your city. Living in a northern city, me being in Seattle, one of the things that I always do is make sure that my students do a mural walk in my school building because we have a mural that tells the history of our school and the Central District, which is the historically Black neighborhood in Seattle. One of the images on the wall is of Martin Luther King, and many students just think it’s there because he’s a great civil rights leader. But what they learn through the mirror walk, and in fact, is that he’s painted there because he came to Seattle one time. On his trip to Seattle he actually spoke at Garfield High School, right there at our own school. What I emphasize with them is that he didn’t just speak about the Southern movement and what he’d been doing in the struggle in the South, he spoke to the fact that Black people couldn’t get decent jobs in Seattle. He spoke to the fact that this neighborhood was redlined, meaning that Black people were forced to live in that neighborhood and refused loans if they tried to leave the Central District. They’re amazed to hear that the struggle happens right here in our own city. So, Jeanne, can you comment on why it’s important that people learn the history of struggle in their cities?

Theoharis: One of the things we were talking about was local struggles in the cities that either they’re in or they’re teaching about and what it would mean to actually get to teach that in school, and what it would mean for students to get to see the place that they live as a place of struggle. I was telling Jesse and Cierra that I did my first book talk a couple of months ago at a prison. I’d never done one before. I was at Wallkill [Correctional Facility], which is about an hour and a half north of New York City. The men there, most of whom are from New York City, had read A More Beautiful and Terrible History and we had this great conversation about Northern injustice. They were thinking about their own school segregation experiences. But, over and over they said to me what it would have meant to see this place that they had lived in as being full of heroes. The figures who challenged that are often presented more as figures that are not political, and what it would have meant to see all of these political activists. So, I think one of the stakes is what does it mean to be able to imagine both yourself in a continuum of activism and of the places that you’re in having a kind of systemic injustice that both needs to be challenged and that people have challenged.

I think one of the stakes is that part of how northern racism survives is that it has this gaslighting tendency towards it, which is that it’s both there but it’s constantly denying itself. So, one of the things that you see if you study the Civil Rights Movement — whether it’s in New York or Boston or LA or Seattle — constantly what you’re seeing political leaders in these cities do is they’re constantly saying to Black activists, “Prove it. We’re colorblind. We’ll even keep records. We don’t even know what students are going where.” They say this. I mean, they must be reading the same manual because when I studied Boston, New York, and LA and these two school officials said the same exact things. So there’s this gaslighting tendency, there’s this way that Northern segregation is constantly there and constantly saying, “No, this is not. No, it’s not. No, it’s not.”

One of the most devastating ways I think that Northern racism is justified is through arguments that say, what I would call culture of poverty arguments, arguments that place the existence of inequality onto behaviors and values that communities develop that are antithetical to success. Again, these kinds of arguments are with us today. You have these narratives that certain parts of the Black community just don’t value education enough; they don’t have the values to succeed in school, which is why you have Black students not doing as well. You see these arguments from the jump after Brown in northern cities. As they said in Boston, “We don’t have inferior schools, we have inferior students.” You see the school committee members saying that in the early 1960s.

So, to me one of the biggest differences between Northern segregation and Jim Crow — and I actually just edited a book with Brian Purnell of new research on the north, called The Strange Careers of the Jim Crow North, because I think we have to talk about the North as Jim Crow — but one of the one of the key differences, I think, is the ways that northerners don’t tend for the most part to be willing to celebrate segregation now and forever, and instead have a variety of different discourses used to mask and justify inequality. The most damaging is this recourse to these cultural arguments, and those students carry with them to this day. They also internalize that idea that certain communities don’t work hard enough or that if you just have different values for success, that that’s how communities succeed, as opposed to some schools that have class sizes of 35 and some schools that have class sizes of 21.

Hagopian: Exactly. Excellent. Well, we’re getting some good questions coming in so I want to ask you a couple of these. Professor Theoharis, do you agree with the idea that the groundwork for the Civil Rights Movement in the North was laid in the 1950s by Malcolm X, the NOI, arts leaders like Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis, and the whole culture of resistance that coincided with or even predates what we understand as the Civil Rights Movement?

Theoharis: I mean, I certainly think that’s one strand. But I think that where I would be a little hesitant is that it also privileges certain leaders we know and misses, I would argue, parent activists. So again, I talked about it very briefly, but one of my favorite stories of New York is the Harlem 9, and the mothers who organized to keep their kids out of school. That’s in the later 1950s. One of my favorite activists in that struggle is Mae Mallory. Mallory is one of those mothers who keeps her kids home, and she’s gotten increasingly enraged about her kids’ schools, including that they don’t have functioning toilets in many of the schools in Harlem at this time. And including that her son comes home and starts to count the pipes under the sink, and she’s like, “What are you doing?” It turns out that this was the teacher’s assignment. [Mallory] asks why they’re having this assignment and it’s basically because the teacher is grooming her son to be a plumber. And not to go on. So, tracking is a huge feature of segregation, and particularly segregation in these Northern cities.

So I would say, absolutely there is a strand of people like that. Again, we can think of Malcolm X also as a local civil rights leader, and he’s based in New York, in Harlem and Queens. He lives in Queens, but there’s also other local activists on the scene, too. At the same time as this, if we think of the narrative of the Southern heroic movement in the post-1954 era, we have the same people in New York doing things right alongside — whether it’s in Little Rock, whether it’s in Birmingham, you have people in all these other places outside of the South doing these things at the same time. It’s not just after 1965, which is where I think you started our conversation today.

Hagopian: Right. Excellent. Well, we have another question from Mason, who is interested in how the current controversy around charter schools plays into the desegregation conversation. On the one hand, they rely on privileges like transportation and pull money from public schools. On the other hand, they provide a public alternative for families that are struggling in the school districts and can’t afford or aren’t able to opt into private school.

Theoharis: Noliwe Rooks has this great book, Cutting School. I think one of the things she always reminds us of is how much money there is to be made in segregation. There’s both how much money there is in keeping the school segregated, but then these constant solutions, that we can’t understand charter schools as a solution because they’re constantly touted as a solution to help our Black kids without understanding that they trade on segregation. They profit from segregation in many ways.

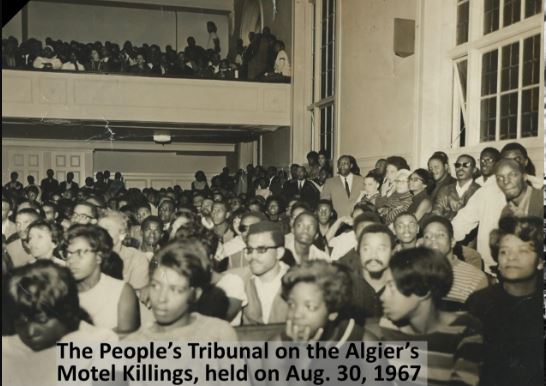

I saw somebody asked a question about LA. LA is also near and dear to my heart. I mean, one of the most damaging narratives, I think, found in our textbooks is this idea that Watts explodes out of nowhere. They tend to get written, we have the voting rights and then three weeks later Watts exploded. And that’s typically the first time we see them in the sections of our textbooks on the civil rights era. But how would it change that textbook if we actually had a history of the Civil Rights Movement in LA pre-1965? A Civil Rights Movement that was taking on school segregation; a Civil Rights Movement that was taking on police brutality?

If we’re going to talk about Malcolm X, in 1962 in LA there’s a confrontation between the police and the Nation of Islam that leaves Ron Stokes and a number of members of the Nation wounded. You begin to see this united front struggle around police brutality in the city, and Malcolm comes out to join it. Elijah Muhammad calls him home. This is a really pivotal moment, I think, in why Malcolm is going to leave the Nation. We often talk about that just in moral terms, but I think we need to also talk about the political, and people do. There’s this movement around police brutality for years before 1965 that gets nowhere, and the city is constantly gaslighting it and constantly saying, “Black people are the problem; we’re not the problem.”

And then you have this whole long struggle in LA and in California around housing segregation. Finally, in 1963, a law passed at the state level outlawing discrimination in rental and sale of property. And what do you get? You get it because in California you have those propositions, you have realtors and local white people get together and get a proposition on the ballot in 1964, basically to repeal the Fair Housing Act. And they succeed. In 1964, Californians — by two to one majority — send Lyndon Johnson back to the White House, and at the same time by a two to one majority, they say we want the right to be able to discriminate in the sale and rental of our property.

Dr. King will talk about this, as King is in LA a whole bunch in 1964, joining with groups fighting Prop 14. He will talk about this as a vote for ghettos and this being one of the — if we’re going to see the various things that lead to the Watts rebellion — one of them is this whole long struggle around fair housing and then the passage of Prop 14.

Thank you for raising the struggle in LA, because I think the Watts uprising looks very different when you see years of struggle that has really gotten nowhere on school segregation, this backlash against progress on housing segregation, and then again, also no progress on police brutality.

Hagopian: I want to ask one last question. But first, I’m so glad that you raise Professor Rooks’ work in the book Cutting School. I would highly recommend everybody read that book. She introduces the term “segrenomics.” Like you said, the money that’s to be made off of segregation. I don’t blame teachers or Black families at all that are looking for an alternative to the racism that exists in traditional public schools and are looking to get out of there and try charter schools as a hope for something different. But when you look at the statistics, charter schools are actually more segregated than the rest of the public schools. Then you look at the way that they siphon off money from the rest of the public schools. In the world’s richest nation, we could fully fund education and have community schools that have wraparound services. I mean, it is a crime against humanity that there’s not a nurse in every school in America. We could afford that. And now in this time of COVID-19, we know that it’s a crisis if we don’t, and yet people want to have a separate school system rather than just fully fund the entire school system. So I appreciate you raising that point, as well.

There’s a question also about how struggle occurred, multiracial solidarity and struggle and what it looked like. Maybe you could talk about some of the walkouts in LA and other groups, Mexican and Asian resistance and multiracial solidarity?

Theoharis: The fight against Prop 14 that I was just mentioning was a multiracial coalition. You see Asian American groups, Chicano groups, Black groups, working in 1964 to try to prevent the passage of Prop 14. One of my personal favorites in LA is what we tend to call the East LA blowouts. In 1968, Chicano students blow out of five high schools on the eastside of LA. But what we don’t often put in that narrative is that there’s also Black students who walked out on that very same day in south LA. We often segregate this history. I’ve gotten really interested in these moments where you see people coming together. I have started to research that and I’m trying to figure out how Black and Chicano students, where they’re meeting and how they come to this. But, you see both Black and Chicano students saying in 1968 that they’re picking up the struggle of their parents, that their parents had been struggling against these conditions and basically had gotten very little change. Then you see this younger generation picking up the struggle.

I also noticed people talking about Milwaukee. I grew up in Milwaukee. If you haven’t read Patrick D. Jones’ Selma of the North, it’s really a lovely history of the Civil Rights Movement in Milwaukee. And it’s really interesting. People mentioned Father James Groppi, this white Catholic priest who worked with this group of Black Power youth. This really interesting movement develops in Milwaukee and obviously some of the scenes from Milwaukee, particularly as they’re engaging this open housing struggle in Milwaukee, if we didn’t know they look like they’re in the south, with that violence and anger, the visuals.

Hagopian: Yeah, absolutely. There is so much rich discussion that we’ve had today, and I hope that it will spark people’s curiosity and they’ll go forward and read more. I hope it leads them to research their own cities and learn about the history of struggle in their own cities. It’s just been a pleasure sharing this time with everybody here today. These are really scary and difficult times as we face the global pandemic of Coronavirus, and building this community of resistance together and discussing these lessons has been really meaningful to me.

While this transcript was edited, there may be minor errors or typos — if you notice something you believe to be incorrect please contact us at zep@zinnedproject.org.

Please consider making a donation so that we can continue to offer people’s history lessons, resources, workshops — and now online mini-classes — for free to K–12 teachers and students. We receive no corporate support and depend on individuals like you.

Sign up for the next session, Peoples Historians Online: Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, on April 24.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn