By Bill Bigelow

In Portland, Oregon, where I live, the 4th of July holiday offers an excuse for a wonderful annual blues festival in Waterfront Park downtown. Unfortunately, in my neighborhood, it also provides cover for people to blow off fireworks that terrify young children and animals, and that turn the air thick with smoke and errant projectiles. Last year, the fire department here reported 260 fires sparked by toy missiles, defective firecrackers, and other items of explosive revelry during the 4th of July “fireworks season” from late June through early July.

Veterans suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder are also at risk. “The sounds of repeated explosions can trigger fits of anger or suicidal thoughts,” warns the Blinded Veterans Association. And there are other health effects of fireworks. The Washington State Department of Ecology warns that “Breathing fine particles in fireworks smoke can cause or contribute to serious short- or long-term health problems. They include: Risk of heart attack and stroke. Lung inflammation. Reduced lung function. Asthma-like symptoms. Asthma attacks.”

Apart from the noise pollution, air pollution, and flying debris pollution, there is something profoundly inappropriate about blowing off fireworks at a time when the United States is waging war — and underwriting war — with real fireworks around the world. In just one example, Airwars.org, which monitors civilian harm from airpower-dominated military attacks, found that almost 30,000 U.S.-led air strikes in Iraq and Syria over the past four years killed at least 6,321 civilians. The pretend war of celebratory fireworks thus becomes part of a propaganda campaign that inures us — especially the children among us — to current and future wars half a world away.

But the yahoo of fireworks also turns an immensely complicated time in U.S. history into a cartoon of miseducation. For example, check out Ray Raphael’s “Re-examining the Revolution” at the Zinn Education Project, an article that every history teacher should read before wading into the events leading up to 1776. Raphael analyzed 22 elementary, middle school, and high school texts and found them filled with inaccuracies—some merely silly, but others that leave students with important misunderstandings about U.S. history, and how social change does and does not happen.

Raphael offers some context for the Declaration of Independence:

In 1997, Pauline Maier published American Scripture, where she uncovered 90 state and local “declarations of independence” that preceded the U.S. Declaration of Independence. The consequence of this historical tidbit is profound: Jefferson was not a lonely genius conjuring his notions from the ether; he was part of a nationwide political upheaval.

Similarly, Raphael reports that

[I]n 1774 common farmers and artisans from throughout Massachusetts rose up by the thousands and overthrew all British authority. In the small town of Worcester (only 300 voters), 4,622 militiamen from 37 surrounding communities lined both sides of Main Street and forced British-appointed officials to walk the gauntlet, hats in hand, reciting their recantations 30 times each so everyone could hear. There were no famous “leaders” for this event. The people elected representatives who served for one day only, the ultimate in term limits. “The body of the people” made decisions and the people decided that the old regime must fall.

As Raphael concludes, “Textbook authors and popular history writers fail to portray the great mass of humanity as active players, agents on their own behalf.” Instead, textbooks credit Great Men — Washington, Franklin, Jefferson — and render all others as “mere followers.”

As Raphael concludes, “Textbook authors and popular history writers fail to portray the great mass of humanity as active players, agents on their own behalf.” Instead, textbooks credit Great Men — Washington, Franklin, Jefferson — and render all others as “mere followers.”

And there is a lot more that complicates the events surrounding the 4th of July and the Revolutionary War. As Raphael notes, “Not one of the elementary or middle school texts [I reviewed] even mentions the genocidal Sullivan campaign, one of the largest military offensives of the war, which burned Iroquois villages and destroyed every orchard and farm in its path to deny food to Indians.” For use with students, see “George Washington: An American Hero?” in Rethinking Columbus, published by Rethinking Schools. In an excerpt included in Rethinking Columbus, Washington wrote to Gen. John Sullivan on May 31, 1779:

The expedition you are appointed to command is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians with their associates and adherents. The immediate object is their total destruction and devastation and the capture of as many persons of every age and sex as possible.

It will be essential to ruin their crops now on the ground, and prevent their planting more. . . .

Parties should be detached to lay waste all settlements around . . . that the country may not be merely overrun, but destroyed. . . .

Those are the orders of a war criminal.

Nor do texts mention the indigenous resistance movements of the 1780s in response to American “settler” expansion, which Raphael calls “the largest coalitions of Native Americans in our history.”

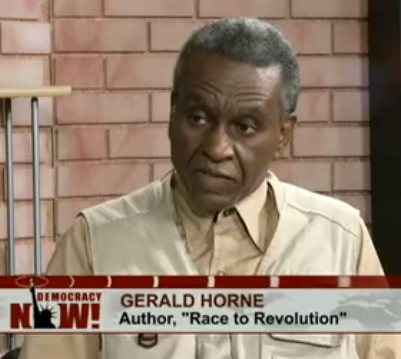

In a recent episode of Democracy Now!, Gerald Horne, author of The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America, points out that more enslaved Africans in the American colonies fought with the British than with the American colonists. As Horne told Democracy Now! hosts Juan Gonzalez and Amy Goodman, “It makes little sense for slaves to fight alongside slave masters so that slave masters could then deepen the persecution of the enslaved. . . .”

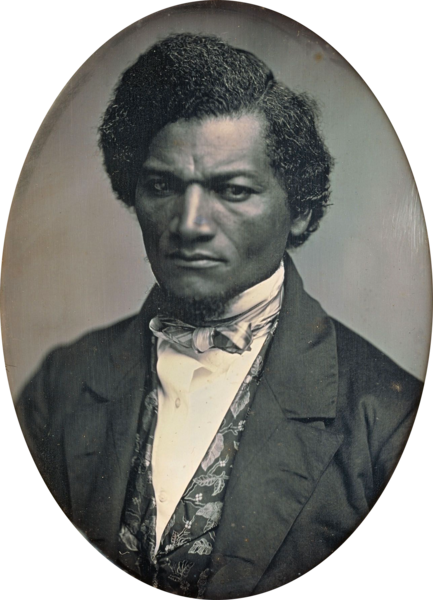

Included at the Zinn Education Project site is a link to Danny Glover, who performs one of history’s most passionate denunciations of U.S. racism and hypocrisy: Frederick Douglass’ “The Meaning of July 4th for the Negro.” Howard Zinn introduces Glover at one of the remarkable “The People Speak” events. Douglass delivered the speech on July 5, 1852 in Rochester, New York, at a Declaration of Independence commemoration:

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sound of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants, brass-fronted impudence; your shout of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanks-givings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of the United States, at this very hour.

Douglass delivered his speech four years after the United States finished its war against Mexico to steal land and spread slavery, five years before the vicious Supreme Court Dred Scott decision, and nine years before the country would explode into civil war. His words call out through the generations to abandon the empty “shout of liberty and equality” on July 4, and to put away the fireworks and flags. In the spirit of Frederick Douglass, the Zinn Education Project urges teachers to use July 4 as a time to rethink how we equip students to reflect on the complicated birth of the United States of America.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

Published on: Huffington Post | Popular Resistance | ZNet.

© 2014 The Zinn Education Project; updated 2018.

Image Credits

- Fireworks over New York City: Wikicommons

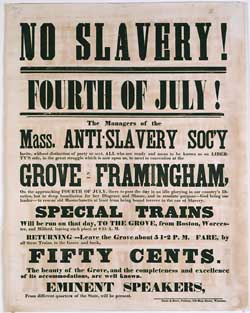

- “No Slavery” broadside: Massachusetts Historical Society website

- Danny Glover Reads Frederick Douglass: Voices of a People’s History

- Frederick Douglass portrait: Wikicommons

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn