By Bill Bigelow with contributions from members of the Taíno Community

This role play begins from the premise that a genocide was committed in the years after 1492, on the islands inhabited by the Taíno. Many Indigenous scholars estimate somewhere around 5 million Taíno inhabited the Greater Antilles pre contact.

Who — and/or what — was responsible for this genocide? This is the question students confront in this activity.

The intent of the lesson is to prompt students to examine the roots of colonial violence. When I first taught a version of this trial role play, it came at the conclusion of a longer unit about the meaning of the European arrival in the western hemisphere, one which included reading Taíno scholar José Barreiro’s “The Taíno: ‘Men of the Good,’” in Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years, which explicitly critiques the notion of the Taíno as “primitive.” As Barreiro writes, “The Taíno strove to feed all the people, and maintained a spirituality that respected most of their main animal and food sources, as well as the natural forces like climate, season, and weather. The Taíno lived respectfully in a bountiful place so their nature was bountiful.” Barreiro notes that “There was little or no quarreling observed among the Taíno by the Spaniards.”

Students and I also read excerpts from Columbus’s journal when he encountered the Taíno Nation, the Lukayan on the island of Guanahaní (probably San Salvador/Watlings Island), included in Rethinking Columbus, which hints at the violence to come: “They do not bear arms or know them, for I showed them swords and they took them by the blade and cut themselves through ignorance” — a quote that students find chilling. On the third day of Columbus’s first encounter with the Taíno, October 14, 1492, Columbus bragged that “with 50 men they would be all kept in subjugation and forced to do whatever may be wished . . .”

The more students learn about the Taíno, Spain, Columbus’s voyages, and details of Columbus’s strategies to steal wealth and land from the people of the Caribbean — and Taíno resistance — the more effective this trial activity will be. But a caveat: The trial is not an introductory activity. A critical look at colonialism begins with the people being encountered prior to colonization, not with the state of siege that they experienced.

This lesson was originally written in 1991. Many things changed over my 30-year teaching career, but one thing stayed sadly consistent: Year after year, my high school U.S. history students had never heard of the Taíno people. Early in my classes, I asked students if they could name the person some people say “discovered America.” There was never any shortage of students calling out “Columbus!” Then I asked, “OK. Who did he supposedly ‘discover’? Who was here first?” Sometimes a few students would say, “Indians.” But I’d say, “No. I mean what was the specific name of the people he found?” In all my years of teaching, I never had a single student say: “The Taíno” — much less be able to name any individual Taíno. I told my students their name, and that there were possibly millions on the islands of the Caribbean. “What does it say,” I asked, “that we all know the name of the fellow from Europe, a white man, but none of us can name who the original peoples of the Caribbean are?”

“The Taíno vs. Columbus, et al.” was — and is — part of a broader effort to bring Taíno peoples into the curriculum. Although this lesson is not designed to introduce students to Taíno culture, the enormity of what happened to the Taíno is at the heart of the lesson. Columbus’s actions against the Taíno meet the United Nations’ definition of genocide (“acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group”) — as well as internationally recognized crimes against humanity, war crimes, and environmental crimes. But there has been an almost complete curricular erasure of the Taíno peoples. Thus, it is up to us as educators to address these gaps, and consult and collaborate with those harmed to address misleading colonial narratives in our classes.

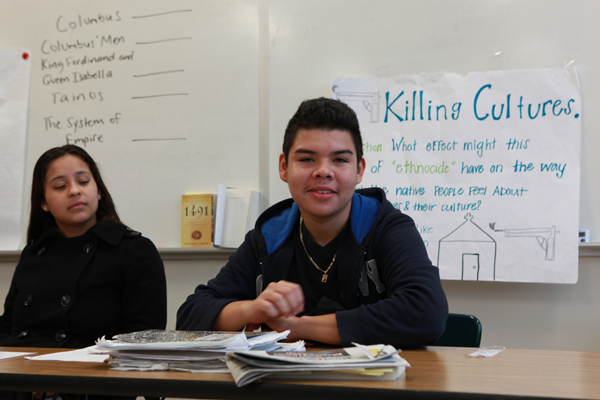

The updated version of this activity centers the Taíno people as the people harmed and includes indictments for four colonial offenders: Columbus, Columbus’s Men, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, and the System of Empire.

A pedagogical note: Recently, there has been much discussion — and controversy — about role plays. It’s a term that embraces strategies the Zinn Education Project supports, and others we oppose. Some school activities — “role plays” — demand that students “recreate traumatic experiences,” in the words of Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Ohio State University professor. No Zinn Education Project activity engages in this kind of teaching. In this and other ZEP role plays, we do not ask students to perform. Although Columbus enslaved Taíno people, and ordered his men to spread “terror,” as documented by the Spanish priest Bartolomé de las Casas, students do not act any of this out in this role play. Instead, the role play asks students to attempt to represent different individuals’ and social groups’ points of view, to wrestle with who or what was responsible for the crimes against the Taínos. The “drama” in this activity is sparked by the intellectual and ethical questions students discuss, not by reenacting historical events. [Read How to — and How Not to — Teach Role Plays.]

Read suggestions for adapting to upper elementary classroom

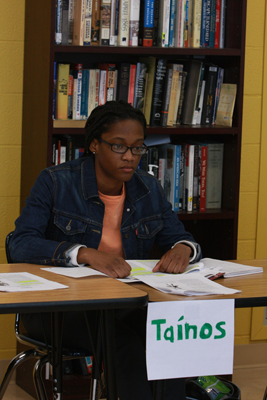

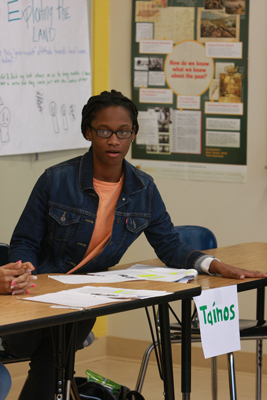

Taínos

The trial role play is excerpted from Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years, which includes more context for the events dealt with in the lesson, including “The Taínos: ‘Men of the Good,'” by José Barriero; a critical reading activity of Columbus’s diary on his first contact with Indigenous people; a timeline of Spain, Columbus, and Taínos with teaching ideas; and an adaptation from the writings of Bartolomé de las Casas on the first Spanish priest to denounce the Spanish brutality in Hispaniola.

The trial role play is excerpted from Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years, which includes more context for the events dealt with in the lesson, including “The Taínos: ‘Men of the Good,'” by José Barriero; a critical reading activity of Columbus’s diary on his first contact with Indigenous people; a timeline of Spain, Columbus, and Taínos with teaching ideas; and an adaptation from the writings of Bartolomé de las Casas on the first Spanish priest to denounce the Spanish brutality in Hispaniola.

We also recommend Indigenous Cuba: Hidden in Plain Sight by José Barreiro in the National Museum of the American Indian and Whose History Matters? Students Can Name Columbus, But Most Have Never Heard of the Taíno People by Bill Bigelow in the Zinn Education Project “If We Knew Our History” series.

Authors

Bill Bigelow is curriculum editor of Rethinking Schools magazine and co-director of the Zinn Education Project. Read more.

Members of the Taíno Community. This version of the lesson was revised in collaboration with Tanya Rodriguez (National Institute for Racial Equity) and the Grandmothers Council Bohio Atabei — Verona Iriarte and Naniki Reyes Ocasio. Additional feedback was provided by the United Confederation of Taíno People.

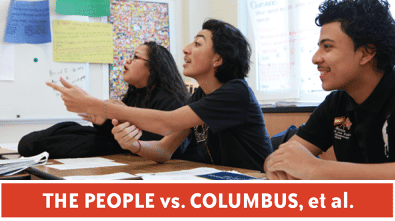

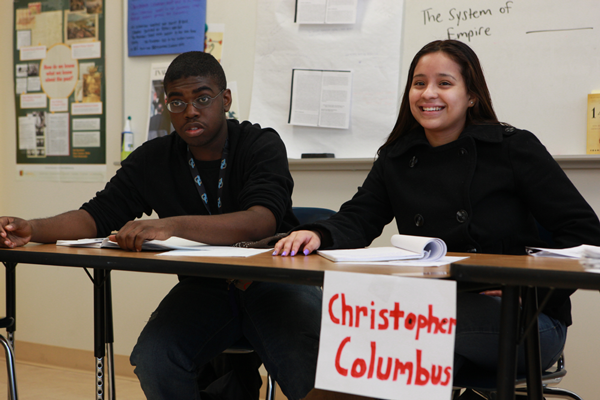

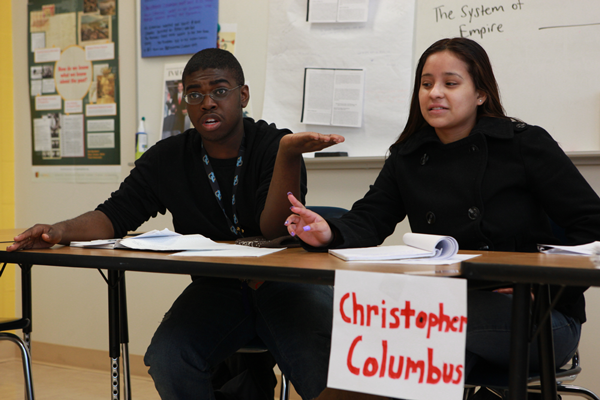

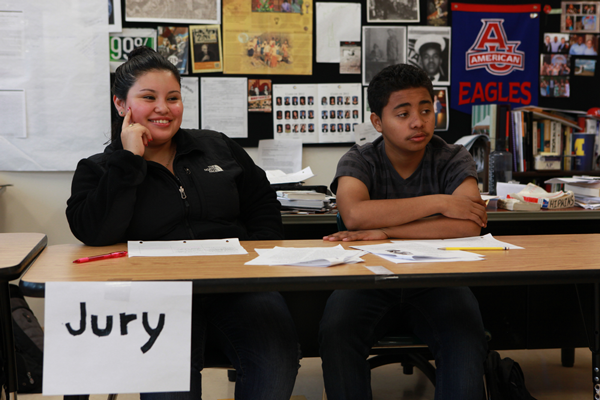

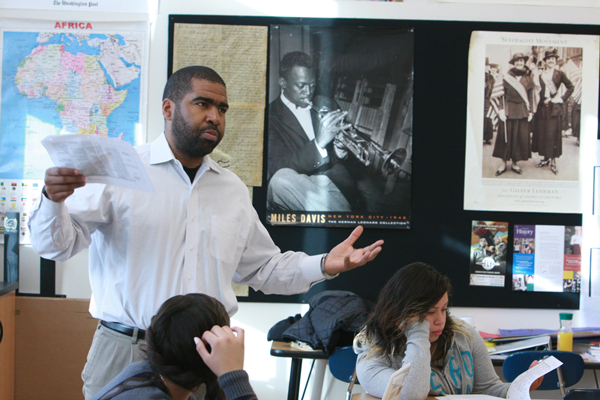

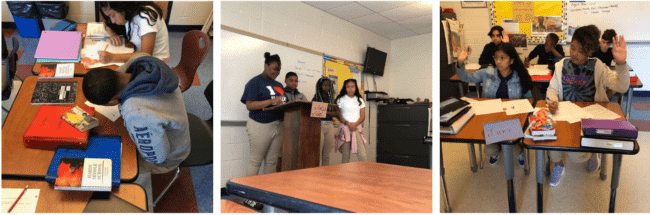

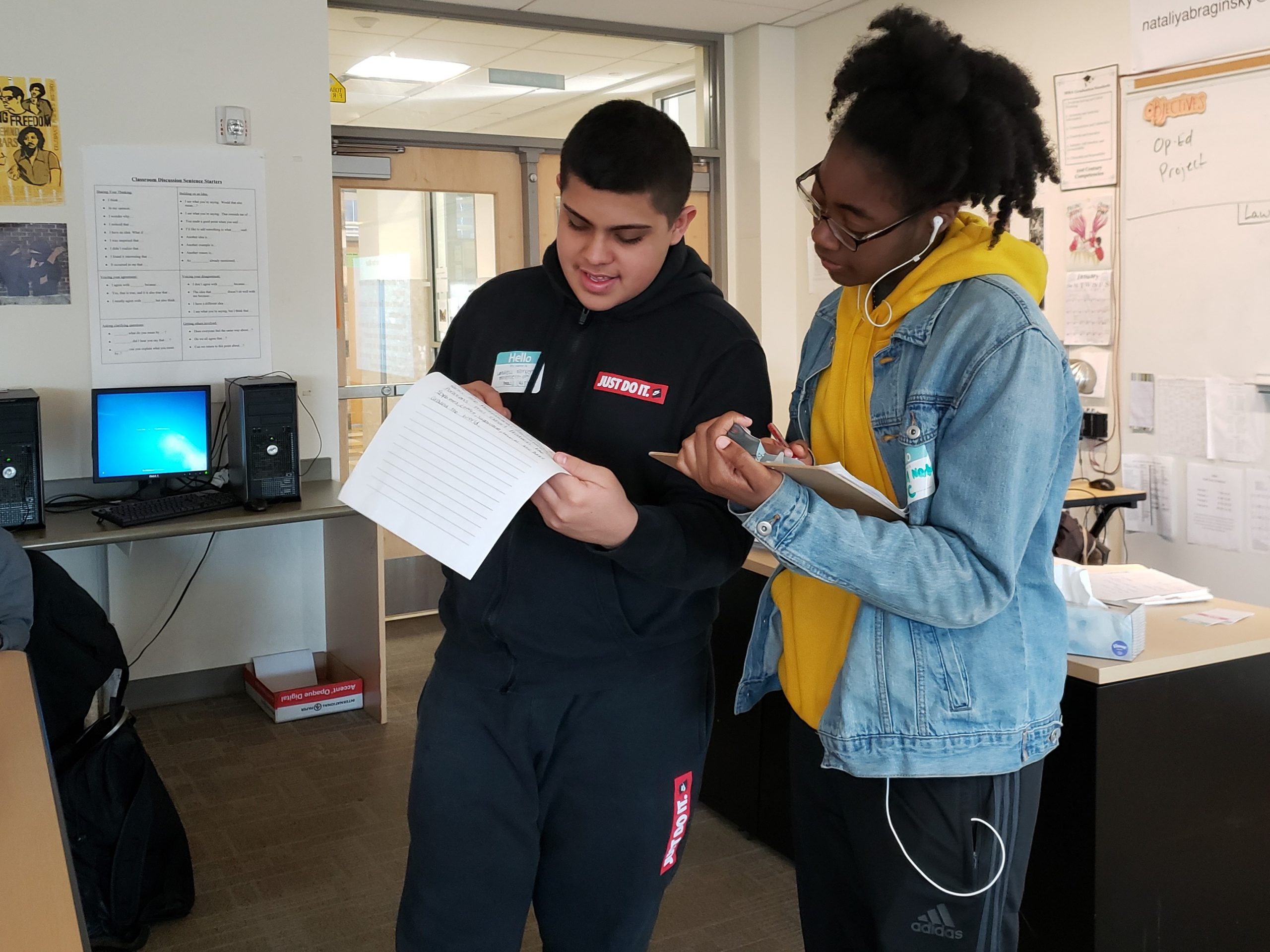

Scenes from the Classroom

Students engaged in the People vs. Columbus trial. (Teacher: Julian Hipkins, 11th grade at CCPCS in Washington, D.C. Photographer: Rick Reinhard, 2012)

Stories from the Classroom

“Guilty or Innocent? Hardy Middle School Students Put Columbus on Trial”

By Cierra Kaler-Jones

If you had to put Christopher Columbus on trial for murder, would he be considered guilty? Students in Caneisha Mills’ 8th-grade U.S. History class at Hardy Middle School in Washington, D.C. grappled with this question when they were assigned the task of deciding who would be considered guilty for the deaths of millions of Taínos on the island of Hispaniola in the 1490s . . .

Continue reading this play-by-play account of The People vs. Columbus, et al. at DC Area Educators for Social Justice.

The People vs. Columbus trial has been my most successful and popular lesson in the two years I taught it. Not only do students get to learn the extent of the atrocities committed by Spanish colonizers, but they get to engage in higher order thinking (one of my grad school buzzwords I think about a lot!) on the factors that cause historical atrocities to occur.

I LOVE how “the system of empire” is one of the options for students to blame or defend. This has generated some of the most challenging discussions I’ve seen in my class so far, as students say, “The king and queen would not have sent Columbus if they hadn’t been acting within the system!” and retort, “But the system is made up of individuals, and each have their own choices!” This thinking about structure vs. agency is a level of thinking in social studies that was not made explicit to me until college, and I am thrilled that this assignment has given my students an opportunity to delve into core disciplinary questions.

They get excited about it, too ― I’ve had students leap up in the trial, hollering their positions to each other in attempts to convince a jury of their peers. At the end of the trial this year, as the jury came back with the verdict, one of my students reflected, “I think that Columbus is like Trump, and the Tainos are like the Mexican people…” This prompted a discussion about how colonial-type oppression works in our current society, leading one student to observe, “You know, I think WE live within a system.” I asked them if they thought that they had any agency within the system, and they had a really thoughtful conversation about it.

Your resources truly fill a well left dry – not by forgetfulness, but by the same racist systems that perpetuate the injustices my students face on a daily basis in schools.

The Zinn Education Project made untold history come to life for students working on the People vs. Columbus tribunal. Students were immersed in building background knowledge by reading the indictments, working together, and using teacher-created graphic organizers to build a defense and a strong prosecution.

The lesson captivated the attention of my students in the online environment, fostered collaboration and highlighted rigorous writing, reading, and speaking & listening standards as we work our way through a delicate piece of history that not many know and everyone should appreciate.

Students remarked at the end of the first day in trial how fun and engaging the work was and how much they were learning by working together, interacting with the teacher and rereading the indictments to write argument pieces to present to class. Seeing the students produce quality work aligned to standards and related to our curriculum content is a magical feeling for a teacher and I for one am humbled it happened in my classroom.

I am grateful I had robust materials to use, a guide for instruction, and the opportunity to create. I am eager to continue to use more Zinn Education Project resources with my students in the future.

This school year has been riddled with uncertainty and confusion. For my students, it has also been distant. Socially distant, limited engagement, cameras off, muted, seldom chat. The People vs Columbus, et al. lesson stands out as an outlier for participation. Even over Zoom, students became active participants, engaged, and passionate about their opinions. While working in groups there was very real collaboration that led to detailed and nuanced arguments. The activity pushed students into discomfort about facing the actual history of trying and horrendous acts.

The trial really allowed students to dig into the nature of responsibility and actions. It showed students the difference between individual actions and the responsibility attributed to the systemic nature of power and privilege. The structure of the trial, one splitting the class into different perspectives, allows students to push beyond their own assumptions and point of view, to see the issues of the past, and apply them to a contemporary dilemma.

Lancaster, Pennsylvania Teacher

In U.S. history with my 11th-grade students, we began the year by corroborating Columbus’s story and used texts from A Young People’s History, traditional textbooks, videos, and other primary sources. They were shocked and surprised at his actions but also surprised that they hadn’t learned this information before.

A perfect culmination to this set of lessons was The People vs. Columbus, et al. The students used their various resources to craft an argument and counter-arguments, and we had a debate about who was responsible for the genocide. They passionately took on their roles and characters, using textual evidence and thinking critically. It has been one of their favorite lessons since the school started and I know they want to participate in more debates!

This lesson perfectly combined speaking, listening, reading, and writing skills, all so that students could have a better understanding of the past.

The science teacher told me that students were arguing during lunch about The People vs. Columbus et al. trial and who was to blame. This was the first time all school year he has heard students really talking about what they were learning outside of class time. To hear ninth graders thinking critically about how much of a person’s action reflects individual choice vs. what society compels them to do and then applying that to major events in world history is amazing. Thank you, Zinn Education Project.

I have used the lesson on colonization and the genocide of the Taínos for many years with my 7th graders. I give them primary and secondary sources to read first so that they can analyze perspective and bias. Then I put them in roles as defense lawyers for each of the teams, witnesses, court reporters, a jury, and a judge. The lawyers read the indictments from the Zinn Education Project and use the sources to help them come up with arguments to defend their sides. The jury summarizes the indictments to be read during the trial. The lawyers come up with opening and closing statements and witness questions. The witnesses prepare responses to the questions they will be asked, the judge prepares a script to be read during the trial.

The mock trial format of the lesson helps students to think critically about the history of the genocide and to craft arguments using evidence to enhance their position. Students become really passionate about the trial and many express their desire to be a lawyer at the end of it. Ultimately, students are divided about who they think is to blame for the genocide, which sets up a really nice conversation with students that there is no “right or wrong” and that many people, as well as the system of the empire, are to blame.

This has fostered really high-level discussions in my class and has allowed students to use their voice effectively while developing persuasive arguments. I love how organized the Zinn Education Project is and how they foster engagement in students. It is something I will continue to use for years.

I have used so many Zinn Ed Project lessons, but the People vs. Columbus, et al. lesson had a profound impact on my students. They really got into the debate on imperialism and how attitudes of white superiority really cause most of the problems for marginalized people. It was really eye opening to hear their thoughts.

My students really appreciated reading from the different perspectives and looking at the event through different lenses. Plus, anytime they have the opportunity to discuss and debate it’s a plus. Students don’t usually get the opportunity to see events from different lenses, and this is so important for historical thinking skills. I appreciate all the Zinn Ed Project materials that provide this.

The People vs. Columbus trial was a perfect start of the year assignment for my 8th graders, and they were absolutely excited to put Columbus on trial and develop questions and statements to roleplay the characters that they were assigned. I will definitely be using this lesson again in the future.

Additionally, it was a great way to get the other teachers on campus involved in my classroom since the students asked and got other teachers and administrators to come in and help judge the trial with me. They were excited to show other staff members the work they were doing to counteract the systems of oppression that were set up at the start of colonization. As Brown and Black students, they were excited to really look into the history of oppression that exists in our nation and argue about what or who made the underlying factors in developing the systems of oppression in the United States. The trial also helped develop conversations about why the systems still exist.

When I first came across this website, one of the first activities I read was People vs. Columbus, et al. and I immediately began preparations to use it in my world history classes. After providing background information from A People’s History and various primary sources, we set the trial up.

My students’ reactions after the trial concludes can easily be described as unsettled. Never before had they heard of the crimes committed against the indigenous peoples of the “new world.” Never before did they realize the impact Europeans had on the indigenous peoples of the western hemisphere.

I have a writing assignment attached to this activity. In two paragraphs, I ask that they tell me who they think is to blame for the crimes. I also ask if they think we should still celebrate Columbus Day.

Afterward, we take a look at our textbook. We look at the one paragraph devoted to Columbus in which it describes his ability to persuade Queen Isabella in 1492. That’s it. That’s all it says. Thanks to the Zinn Education Project, my students have a better understanding of the impact left by him and other Europeans. Now, they know more than just the year he sailed and the color of the ocean.

I always begin my U.S. history course with the People vs. Columbus, et al Trial. It is amazing how engaged students become to not only learn the truth but also be able to defend themselves using the evidence provided. Students love creativity and this case allows students to come to their own conclusions.

I used the The People vs. Columbus, et al. lesson plan when I was a student teacher during the school year of 2020–2021. The lesson was very engaging and it encourages students to think about the causes and effects of European arrival to America.

Students were able to generate their authentic ideas regarding the slaughter of the Taíno Community. The lesson allows students to think about history from different perspectives and the activity encourages students to develop critical thinking skills. Since students have to participate in a trial, they were also able to develop public speaking skills.

In my years in the classroom, I utilized several lessons from the Zinn Education Project. Most notably, I utilized the People vs. Columbus, et al. lesson and accompanying activities. As luck would have it, one year I had a student teacher who was pursuing education as a second career — his first being a lawyer! That year the trial was exceptionally professional.

Something I always included after the People vs. Columbus, et al. lesson is presenting students with the book Encounter by Jane Yolen. First, I check out many children’s books about Columbus from the local library and have students flip through them. Then, after getting a general consensus about them, I showcase Jane Yolen’s book, which is one of the only books I’ve ever come across that presents the story of Columbus from the Taínos’ point of view — and a child’s perspective at that!

More Classroom Stories

As a teacher, the Zinn Education Project website is invaluable because it provides activities that directly relate to A People’s History. Last week we did The People vs. Columbus, et al. which places all the parties involved in the arrival of Columbus on trial for the murder of the Tainos. The activity was so interactive that teachers from other classrooms had to ask us to quiet down. Students were able to better understand the motives and consequences behind the arrival.

Even though A People’s History can be a bit difficult for some students, the activities on the Zinn Education Project website makes the content accessible regardless of their reading level.

Every year when I discuss the European Age of Exploration with my students, I spend time using the materials included in Bill Bigelow’s excellent The People vs. Columbus, et al. lesson. However, instead of making it a trial that students participate in directly, I have it set up as a murder mystery: who is responsible for the deaths of all of these people? Though the format that I use is different than what Mr. Bigelow recommends, students still find the lesson engaging — the idea that they not only get to be critical of historical decision-makers, but also get to have agency over which one is the worst gets them involved with the topic.

Within this murder mystery, students act as a detective, gathering evidence from Mr. Bigelow’s summaries and from other sources I have gathered. In the end, they need to write up a police report and prepare information to present to a grand jury. Students share their findings and then they debate who they believe is most guilty of the deaths of the Taíno people.

My students were completely engaged in The People vs. Columbus trial we held about the massacre of the Taíno people. They loved it! They were so outraged that Columbus Day is a federal holiday that I suggested we send letters to the editors of local newspapers and our city council. They were so excited. Most of the students chose to send letters. When a student’s letter was published the next day advocating for our city to celebrate Indigenous People’s Day, the students who had not yet sent letters immediately began to write their own.

It was a powerful lesson in civics, especially since my students are disenfranchised and feel like they don’t have power to effect change politically.

When I do the Christopher Columbus lesson, the students are blown away. They are usually so surprised at the truth behind Columbus. They also love the role-playing. This year, when I was doing the lesson, my assistant principal walked in just as one of the students who usually sits quietly during social studies was standing up and asking a fiery round of questions to the defendants on the stand. I was so impressed with it. The lesson also gets students who I usually don’t get a lot of participation out of to debate with the students who I do. I love it!

The People vs. Columbus trial was so effective. I taught it in a Native American Studies course and the students spent a lot of time exploring primary source documents from Columbus and Las Casas.

It was powerful to watch them transform into excellent and passionate litigators, but basing their arguments upon historical evidence. Also, the power of role plays to induce empathy and compassion for various points of view was evident.

My students are all Native American and they are all too familiar with the concepts of genocide and exploitation. However, many of them did not know about the Taíno and were curious to learn more. At the conclusion we watched the film Even the Rain to enhance their understanding of the texts, and also to learn more about the Cochabamba water war to piece together an interdisciplinary unit about water that they were engaged in.

The Christopher Columbus trial is a phenomenal lesson to use with students. First, it forces them to think about the construct of our globalized world in a new and critical manner. Americans are bred upon the unchallenged idea of superiority and equality, and it is troubling for them to have to see that the true pillars of trade, colonization, exploration, and expansion are instead rooted in forced inferiority and exploitation. This lesson further challenges students to give up the stereotypes and nostalgia surrounding Native Americans (in this case on Hispaniola) and see them as people who had functioning societies and belief systems. The most powerful aspect of the lesson, however, is the way it forces students to research, utilize primary resources, think in a debate-like manner, and justify their positions with evidence.

One of my students returned to visit me last month to inform me that because of partaking in this lesson last year, he joined an online group advocating the end of Columbus Day. I was impressed to have a 10th grade student not only take a firm stand on something, but actually take action to incite change. Another of my students said that this “was the best lesson I ever learned because it helped me believe that there is ‘real’ history I can learn from.”

The People vs. Columbus lesson was transformative in my classroom. Students were initially motivated by the competitive aspect of the lesson in trying to “win” during the trial. During the preparation of this lesson, students were able to really practice historical contextualization by looking through various points of view.

Additionally, I supplemented this lesson with primary sources from Voices of a People’s History. Working with the primary sources provoked deep discussion about why certain points of view are omitted or de-emphasized in American History. We compared Las Casas to Columbus and discussed the development of racism and ethnocentrism.

On the day of the trial, students were completely engaged in the process of argumentation, viewing history (in many cases for the first time) as more than just fact, but a series of arguments presented through various frameworks. By the end of the trial, it was clear that blame was very difficult to lay on just one group. It encouraged them to think more critically about a complex web of contingencies that all led to the genocide of the Taínos. They were engaged through the entire unit, practiced presentation skills, research, historical argumentation, and more.

I teach U.S. history to juniors. Our first unit is on the first peoples of North America. Our second unit begins exploring the impact European colonization had the the indigenous people of the Americas. At the end of this second unit, we use The People vs. Columbus, et al in order to critically examine the forces that created and maintained imperialism. I supplement by focusing more time on the Taínos, their rebellions, and their leaders.

Besides being incredibly informative and an excellent way to teach claim and evidence, this Zinn Education Project lesson is also really fun for students. Every year, my students say it is one of their favorite things from the school year, especially for those who enjoy getting into character and “embellishing.” For example, I had lawyers attempt to bribe jury members or the judge, dramatic reenactment of specific conversations or crimes, and more. At the same time, students understand and respect the gravity of the history lesson and the genocide of the Taínos.

I am the secondary guide (middle school teacher) in Davis, West Virginia, at the Mountain Laurel Learning Cooperative, a Montessori learning center for students age 3-14. I developed this middle school program last year, so this is our inaugural year and a big success so far. Our curriculum is centered around social justice, environmental stewardship, and mindfulness.

I rely heavily on the Zinn Education Project for the social justice component of our program. One of the best experiences I had with my students this year was on Columbus Day when we followed the mock trail lesson, People vs. Columbus, et al. The students really got into this activity. The upper elementary students (grades 4-6) joined us to be the jurors and audience. Fervent speeches were made and thoughtful and powerful discussion ensued. My students noted this activity as one of their highlights this fall. Thank you so much for the resource.

The People vs. Columbus, et al. was a unique way to bring the often hidden story of the Taíno peoples to my class. Many students had never been exposed to the unjustified treatment of the Taíno. The activity immersed students in the past and allowed them to hear a new perspective of the “founding” of the Americas. Thank you Zinn Education Project.

Every year I use the Columbus trial lesson from the Zinn Education Project. It’s by far my most popular activity all year. It’s amazing to see all the critical thinking that’s set on fire. It prompts so many arguments, discussions, and discoveries in their outside research. When seniors who’ve had my class come in and see the desks rearranged for the trial, they always exclaim, “Oh, they’re doing the Columbus trial? I remember that! I miss that!” It helps them see the power of greed and how that mindset has affected subsequent historical events. Thank you so much for helping promote so much important learning in my classroom.

Our students were incredibly engaged in the reading and learning and had meaningful group discussions that focused on choices made by Columbus and other explorers and their impact on the world.

Overall, having access to the Zinn reading and activities has encouraged my students to be excited about reading and history, show self-motivated engagement, and look at both the positives and negatives in history without the rose-colored tint that other resources often provide for students.

Maryland does not celebrate Columbus Day, so students are in school. To show the impact of Columbus’s voyage on Indigenous people, this exercise provided an eye-opener for students as well as instructors. It was done with four GED classes that were at various learning levels. Students were randomly selected from each class to participate in the trial and one class served as observers and writers of the exercise. Students were able to show clear critical thinking skills that we rarely use with our other learning materials. The students and instructors truly enjoyed the exercise and it was reported in our newsletter.

I have used the Columbus trial lesson from the Zinn Education Project website, and it went fantastically well. I teach high school Spanish, and this lesson completely changed their outlook on: (1) Who Columbus actually was; and (2) What we as Americans value as a society. I saw their critical thinking skills broaden before my eyes, and the lesson was so easy to maneuver for me!

Plus, the Spanish version of “Los cargos” made it that much easier to differentiate the lessons. Now that they understand the beginning of Europeans in the New World, we’ll continue through the study of Latin American history throughout the next two years. I felt it important that they understand where much of the ill will started in this history, and between Columbus and Pizarro, I now believe that they have a good grasp of that. Thanks for your help in making this AWESOME unit!

In a blog post about this lesson in action, Adrian Hoppel at the Talking Stick Learning Center describes how his students found all parties except the Taíno guilty — and apologized to the Taíno for being charged and being brought to a trial for their own genocide.

In a blog post about this lesson in action, Adrian Hoppel at the Talking Stick Learning Center describes how his students found all parties except the Taíno guilty — and apologized to the Taíno for being charged and being brought to a trial for their own genocide.

Each of the defendant groups did an amazing job defending themselves, pulling all of the obvious rationalizations you’d expect, but also surprising me with some very creative defenses. For example, when attempting to defend The System of Empire, the defendant stated that “while my system, unfortunately, allows for abuse and atrocities, it does not require them; you still have to choose, on your own, to commit them.” I thought that was surprisingly astute.

By working hard to defend each of these groups, the hope was that each group would be examined for its complicity in this crime, and I feel this was most definitely accomplished.

Beyond the Classroom

Student Film Critiques Textbook Accounts and Hero Worshipping

High school student filmmakers Jared, Ana Marie, Jonah, and Mayra (not pictured) made “Columbus – The Hidden Story” for the 2011 National History Day competition.

D.C. high school teacher Julian Hipkins III used The People vs. Columbus, et al. lesson with his 11th grade U.S. history class at Capital City Public Charter School and introduced them to Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States. Four of his students (Jared, Ana Marie, Jonah, and Mayra) were inspired to make a film called Columbus—The Real Story. Using feature film clips and interviews with school staff, the film critiques and analyzes textbook accounts of Columbus. Columbus—The Real Story was selected as a D.C. citywide entry for the 2011 National History Day competition.

Columbus – The Hidden History from Nonchalant Filmmakers on Vimeo.

Has anyone successfully done this project with Middle Schoolers? What suggestions would you give to adapt it to their age?

What America has done to our Shawnee and Delaware People is yet an obscenity and good reason for Christians to repent before they go to hell after the karma of their reincarnations of becoming the people they hated and extirpated -In fact I only half exist since I’m half extinct with Savage Envy.

The Columbus v. the People et al. lesson was transformative in my classroom. —Mia Drabick, high school social studies teacher, Durham, NC

I have used the Columbus Trial lesson from the ZEP website, and it went fantastically well. I teach high school Spanish, and this lesson completely changed their outlook on 1) Who Columbus actually was and 2) What we as Americans value as a society. I saw their critical thinking skills broaden before my eyes, and the lesson was so easy to maneuver for me! Plus, the Spanish version of “Los cargos” made it that much easier to differentiate the lessons. Now that they understand the beginning of Europeans in the New World, we’ll continue through the study of Latin American history throughout the next two years. I felt it important that they understand where much of the ill will started in this history, and between Columbus and Pizarro, I now believe that they have a good grasp of that.

Thanks for your help in making this an AWESOME unit! —Madelynne Brazile, high school Spanish teacher, Florida

I used the Christopher Columbus mock trial this year. My son (a senior in high school), was at my school that day to volunteer after school. He came into my last class of the day and observed the lesson. He said, “Now I know why all my friends loved your class. That was awesome.” —Jeri Shaffer, middle school social studies teacher, Cantonment, FL

My first class graduated this past June and in conversations with them they always tell me how much they enjoyed Social Studies, and will never forget Columbus and how much fun they had learning the truth. Thank you for providing us with such incredible resources over the years. —Ian Godfrey, middle school social studies teacher, Stillwater, NY

The impact from “The People v. Columbus et al” resource is multifaceted. The level of engagement and rigor that this activity can bring about in my students is unmatched by other activities for studying the time period during which Europeans first began to arrive to the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries. I believe that the way in which ZEP pushes students to understand history through a critical lens has made my classroom more engaging, more rigorous, and has prepared my students to be the types of citizens this world desperately needs. —Jose Valenzuela, middle school social studies teacher, Boston, MA

When I used the People v. Columbus, et. al last year, the students were absolutely energized! —Grace Struiksma, middle school social studies teacher, Draper, UT

Maryland does not celebrate Columbus Day; so students are in school. To show the impact of Columbus voyage on indigenous people, this exercise provided an eye opener for students as well as instructors. It was done with 4 GED classes that were a various learning levels. Students were randomly selected from each class to participate in the trial and one class served as observers and writers of the exercise. Students were able to show clearly critical thinking skills that we rarely use with other learning materials. The students and instructors truly enjoyed the exercise and it was reported in our newsletter. —Verona Iriarte, GED preparation in Maryland

The impact has been great. For both cases, I used the Columbus on Trial activity – one at a graduate institute and the other at a proven-risk youth organization for individuals involved with or affiliated with crime and gang activity. Both instances had the participants, ages 17 to 30, invested in the trial and who they were representing – shedding more than just a “holiday weekend (as this activity was done just after the holiday weekend).” More specifically, it opened up for a specific participant to speak about his Tainos background. The activity got a lot of love. —Nick Pelonia, Lowell, MA

Our students were incredibly engaged in the reading and learning and had meaningful group discussions that focused on choices made by Columbus and other explorers and their impact on the world. … Overall having access to the Zinn reading and activities has encouraged my students to be excited about reading and history and show self motivated engagement and look at both the positives and negatives in history without the rose colored tint that other resources often provide for students. —Coral Edwardsen, middle school humanities teacher, Los Angeles, CA

The impact that this had on the classroom is that the students developed a sense of wonder and investigative spirit as they learned the truth about the things that they have learned all their life were incorrect. —Stefeny Anderson, high school social studies teacher, Seattle, WA

When I do the Christopher Columbus lesson, the students are blown away. They are usually so surprised at the truth behind Columbus. They also love the role playing. This year, when I was doing the lesson, my assistant principal walked in, just as one of the students who usually sits quietly during social studies was standing up and asking a fiery round of questions to the defendants on the stand. I was so impressed with it. The lesson also gets students who I usually don’t get a lot of participation out of to debate with the students who I do. I love it! —Chris Olsen, middle school social studies teacher, Chicago, IL

We spend a significant amount of time in our SS curriculum learning about “perspective” and how perspective plays a key role in how we understand history. This trial deeply solidified the students understanding of perspective in a more concrete way. We did this trial on the days after Columbus Day and students continue to reference it when we bring “perspective” up. It’s really wonderful to see a lesson have that big of an effect on student learning while making it fun. —Chloe Hansen, middle school social studies teacher, Wellesley, MA

The Christopher Columbus trial is a phenomenal lesson to use with students. First, it forces them to think about the construct of our globalized world in a new and critical manner. Americans are bred upon the unchallenged idea of superiority and equality, and it is troubling for them to have to see that the true pillars of trade, colonization, exploration, and expansion are instead rooted in forced inferiority and exploitation. This lesson further challenges students to give up the stereotypes and nostalgia surrounding Native Americans (in this case on Hispaniola) and see them as people who had functioning societies and belief systems. The most powerful aspect of the lesson, however, is the way it forces students to research, utilize primary sources, think in a debate-like manner, and justify their positions with evidence. One of my students returned to visit me last month to inform me that because of partaking in this lesson last year, he joined an online group advocating the end of Columbus Day. I was impressed to have a 10th grade student not only take a firm stand on something, but actually take action to incite change. Another of my students said that this “was the best lesson I (she) ever learned because it helped me (her) believe that there is ‘real’ history I (she) can learn from. —Sara Pierce, high school language arts/English teacher, Hollywood FL

I think the People vs. Columbus et al was so effective. I taught it in a Native American Studies course and the students spent a lot of time exploring primary source documents from Columbus and Las Casas. It was powerful to watch them transform into excellent and passionate litigators, but basing their arguments upon historical evidence. Also, the power of role plays to induce empathy and compassion for various points of view was evident. My students are all Native American and they are all too familiar with the concepts of genocide and exploitation. However, many of them did not know about the Taino and were curious to learn more. At the conclusion we watched the film, Even the Rain, to enhance their understanding of the texts, and also to learn more about the Cochabamba water war to piece together an interdisciplinary unit about water that they were engaged in. —Lisa Longeteig, high school social studies teacher, Santa Fe, NM

My students were completely engaged in the trial we held about the massacre of the Tainos. They loved it! They were so outraged that it’s a federal holiday that I suggested we send letters to the editors of local newspapers and our city council. They were so excited. Most of the students chose to send letters. When one of the students letters was published the next day advocating for our city to celebrate Indigenous People’s Day, the students who had not sent letters immediately began to write. It was a powerful lesson in civics especially since my students are disenfranchised and feel like they don’t have power to effect change politically. —Laura Farrelly, high school social studies teacher, Eugene OR

Every year on student evaluations many students point to this role play as one of their favorite projects. After the trial, it is clear that students sense of this history is completely changed. Students often question why we celebrate Columbus Day and why he is seen as a hero. Throughout the year as we move through U.S. history, students come back to the trial and talk about what happened and what they learned in relation to constitution, slavery, and manifest destiny. —Kathryn Cates, middle school social studies teacher, Portland, OR

I am a retired bilingual-bicultural teacher in Chicago. For 17 years I taught second grade in a gifted program at Orozco Academy, in Pilsen, mostly Mexican neighborhood in the city.

Even before Rethinking Schools, published Rethinking Columbus, I always asked my students: “Why we don’t have classes on October 12?” There were many answers, some of them were “Es el día de Cristobal Colon” or “Es el cumleaños de Cristobal Colon” or “Es el Dia de la Raza” or “I don’t know…”

We started the journey of finding out who was that señor Cristobal Colon, Christopher Columbus. Where was he worn, in what time did he lived, what he has to do with us, what believes people have about the world at that time, etc. We look for information,the students designed a questionnaire with 5 questions to ask their parents, or other relatives, like “Did you celebrated Columbus Day in Mexico?” “What do you know about the character” “Should be celebrate what happened in October 12, 1492?” “Was this part of the world inhabited”

etc., etc. By the end of the lesson, the students created a picture book with 12 pages, on each page they draw something related to the “holiday” and wrote one or two sentences for each drawing, and we created a show outside the classroom with all the books. The older students and the teachers were very interested and came to ask questions to our class. They were intrigued why the young second graders decided that October 12 was not a day of celebration, but a time to commemorate the fight of indigenous people in the continent of America, since 1492 to this day, for their rights and dignity.

The trial worked very well on Friday (1/27/2012). Students were very engaged and thoughtful. After school at our staff meeting, one of the Physics teachers shared that he had students arguing in his classroom during lunch and he was about to break them up and send them out when he realized they were talking about the Columbus Trial and who was to blame. He reflected that this was the first time all school year he has heard students really talking about class content outside of class time (even though for his class, students had to solve a murder mystery as their last lab!). I especially loved hearing the “System of the Empire” groups present their arguments and then have other students question them. To hear 9th graders thinking critically and debating how much of a person’s action reflects their individual choice vs. what society compels them to do and then applying that to major events in world history is amazing. Thanks for the resource! – Barrie Moorman, U.S. history teacher, 9th grade, Washington, D.C.

I do research prior to this activity and we read a variety of articles on the topic of Columbus and the Taino’s, including for example, las Casas. Then students write a paragraph answering the question: Should we celebrate Columbus Day. They have to cite sources and support their reasoning. The high level of critical thinking and engagement for the trial is wonderful, as they already have set some ideas up, this activity allows them to rethink.

Jennifer Glowacki

Its a great activity. I conduct this simulation every year.

I always begin my U.S. history course with this case. It is amazing how engaged students become to not only learn the truth but also be able to defend themselves using the evidence provided. Students love creativity and this case allows students to come to their own conclusions. Although, I must say, some of my students have become frustrated with me for not providing them the “answer” to who or what was responsible for killing the Tainos. All I tell them is there is no right answer!