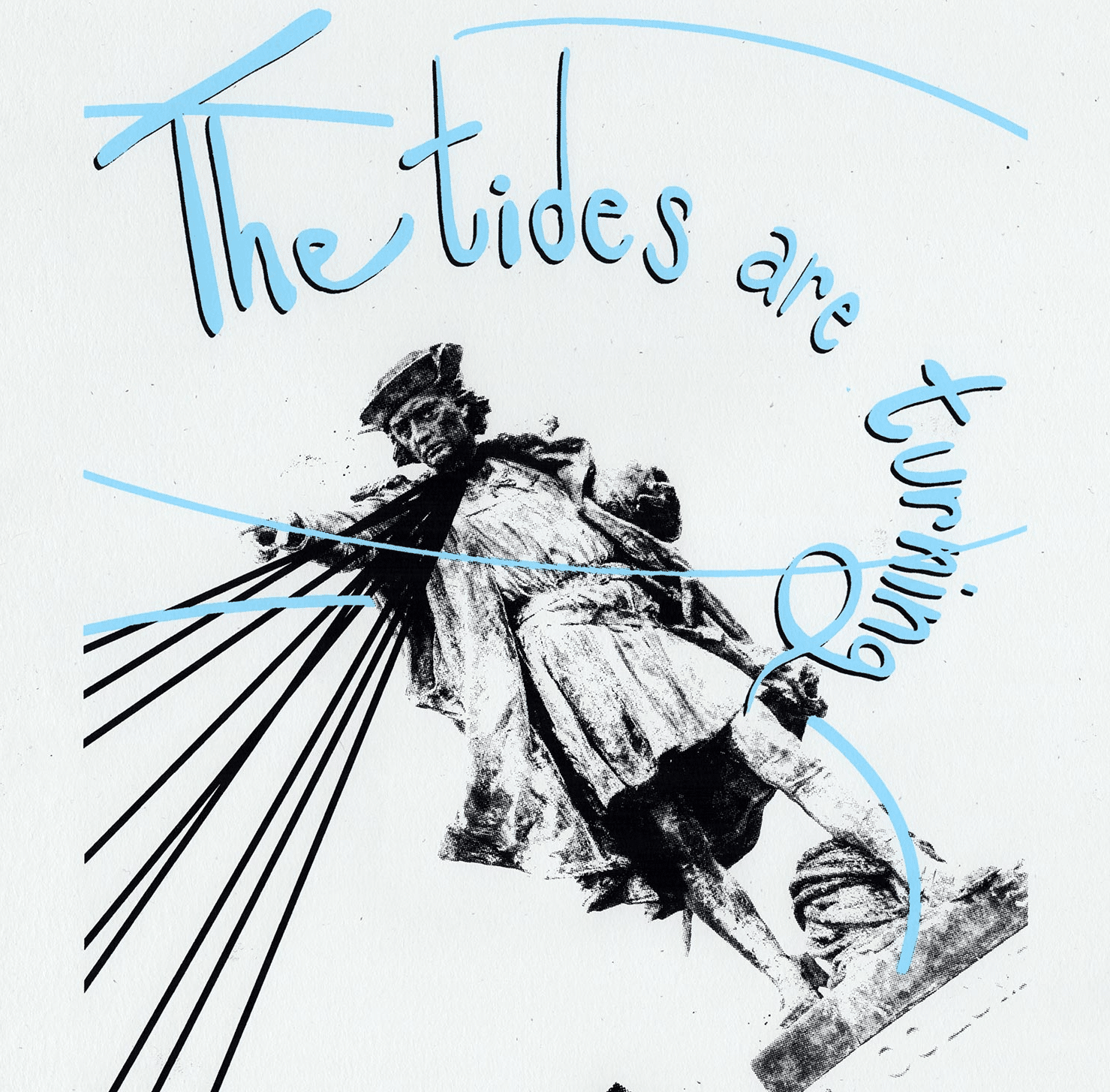

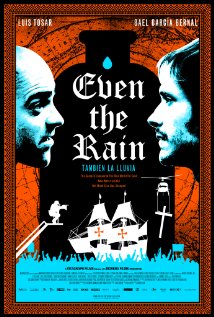

TOP: Some of the books banned in Tucson. BOTTOM: The film “Precious Knowledge” captures the impact and effectiveness of the Ethnic Studies program in Tucson.

By Bill Bigelow

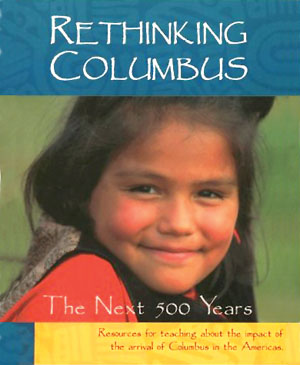

This past January, almost exactly 20 years after its publication, Tucson schools banned the book I co-edited with Bob Peterson, Rethinking Columbus. It was one of a number of books adopted by Tucson’s celebrated Mexican American Studies program — a program long targeted by conservative Arizona politicians.

The school district sought to crush the Mexican American Studies program; our book itself was not the target, it just got caught in the crushing. Nonetheless, Tucson’s — and Arizona’s — attack on Mexican American Studies and Rethinking Columbus shares a common root: the attempt to silence stories that unsettle today’s unequal power arrangements.

* * *

For years, I opened my 11th-grade U.S. history classes by asking students, “What’s the name of that guy they say discovered America?” A few students might object to the word “discover,” but they all knew the fellow I was talking about. “Christopher Columbus!” several called out in unison.

“Right. So who did he find when he came here?” I asked. Usually, a few students would say, “Indians,” but I asked them to be specific: “Which nationality? What are their names?”

Silence.

In more than 30 years of teaching U.S. history and guest-teaching in others’ classes, I’ve never had a single student say, “Taínos.” So I ask them to think about that fact. “How do we explain that? We all know the name of the man who came here from Europe, but none of us knows the name of the people who were here first — and there were hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of them. Why haven’t you heard of them?”

This ignorance is an artifact of historical silencing — rendering invisible the lives and stories of entire peoples. It’s what educators began addressing in earnest 20 years ago, during plans for the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the Americas, which at the time the Chicago Tribune boasted would be “the most stupendous international celebration in the history of notable celebrations.” Native American and social justice activists, along with educators of conscience, pledged to interrupt the festivities.

In an interview with Barbara Miner, included in Rethinking Columbus, Suzan Shown Harjo of the Morning Star Institute, who is Creek and Cheyenne, said: “As Native American peoples in this red quarter of Mother Earth, we have no reason to celebrate an invasion that caused the demise of so many of our people, and is still causing destruction today.” After all, Columbus did not merely “discover,” he took over. He kidnapped Taínos, enslaved them — “Let us in the name of the Holy Trinity go on sending all the slaves that can be sold,” Columbus wrote — and “punished” them by ordering that their hands be cut off or that they be chased down by vicious attack dogs, if they failed to deliver the quota of gold that Columbus demanded. One eyewitness accompanying Columbus wrote that it “did them great damage, for a dog is the equal of 10 men against the Indians.”

In an interview with Barbara Miner, included in Rethinking Columbus, Suzan Shown Harjo of the Morning Star Institute, who is Creek and Cheyenne, said: “As Native American peoples in this red quarter of Mother Earth, we have no reason to celebrate an invasion that caused the demise of so many of our people, and is still causing destruction today.” After all, Columbus did not merely “discover,” he took over. He kidnapped Taínos, enslaved them — “Let us in the name of the Holy Trinity go on sending all the slaves that can be sold,” Columbus wrote — and “punished” them by ordering that their hands be cut off or that they be chased down by vicious attack dogs, if they failed to deliver the quota of gold that Columbus demanded. One eyewitness accompanying Columbus wrote that it “did them great damage, for a dog is the equal of 10 men against the Indians.”

Corporate textbooks and children’s biographies of Columbus included none of this and were filled with misinformation and distortion. But the deeper problem was the subtext of the Columbus story: it’s OK for big nations to bully small nations, for white people to dominate people of color, to celebrate the colonialists with no attention paid to the perspectives of the colonized, to view history solely from the standpoint of the winners.

Textbook depictions of Columbus are often filled with misinformation and distortion or are justified with references to manifest destiny. The bottom image is a woodcut by Theodor De Bry, in the 16th century, based on the writings of Bartolome de las Casas.

Rethinking Columbus was never just about Columbus. It was part of a broader movement to surface other stories that have been silenced or distorted in the mainstream curriculum: grassroots activism against slavery and racism, struggles of workers against owners, peace movements, the long road toward women’s liberation — everything that Howard Zinn dubbed “a people’s history of the United States.”

Which brings us back to Tucson: One of the most silent of the silenced stories in the curriculum is the history of Mexican Americans. Despite the fact that the U.S. war against Mexico led to Mexico “ceding” — at bayonet point — about half its country to the United States, this momentous event merits almost no mention in our textbooks. At best, it is taught merely as prologue to the Civil War.

Mexican Americans were central to building this country, but you wouldn’t know it from our textbooks. They worked in the Arizona copper mines, albeit in an apartheid system where they were paid a “Mexican wage.” In the 1880s, the majority of workers building the Texas and Mexican Railroad were Mexicans, and by 1900, the Southern Pacific Railroad had 4,500 Mexican workers in California alone.

They worked the railroad and they worked for their rights. In 1903, Mexican and Japanese farm workers united in Oxnard, California to form the Japanese-Mexican Labor Association. As Ronald Takaki notes in A Different Mirror, “For the first time in the history of California, two minority groups, feeling a solidarity based on class, had come together to form a union.” They struck for higher pay, writing in a statement that, “if the machines stop, the wealth of the valley stops, and likewise if the laborers are not given a decent wage, they too, must stop work and the whole people of this country suffer with them.”

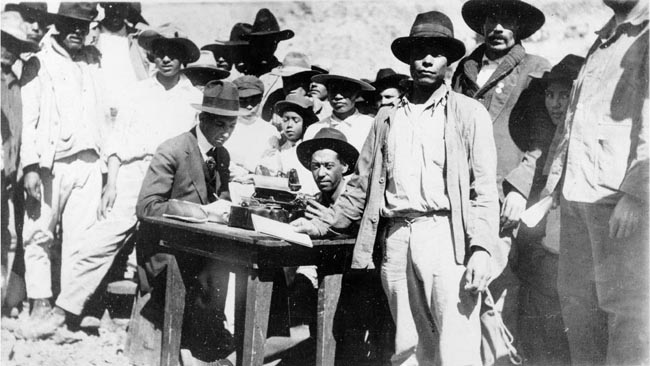

Miners sign up for membership in the Western Federation of Miners in Morenci, Ariz. in 1916. Source: © Henry S. McCluskey Collection, ASU.

Nowhere was this rich history of exploitation and resistance being explored with more nuance, rigor, and sensitivity than in Tucson’s Mexican American Studies program. Like Rethinking Columbus, Mexican American Studies teachers aimed to break the classroom silence about things that matter — about oppression and race and class and solidarity and organizing for a better world. Watch Precious Knowledge, the excellent film that offers an intimate look at this program — and chronicles the fearful, even ludicrous, attacks against it — and you’ll get a sense of the enormous impact this “rethinking” curriculum had on students’ lives.

Let’s continue to use this and every so-called Columbus Day to tell a fuller story of what Columbus’s voyage meant for the world, and especially for the lives of the people who’d been living here for generations. And let’s push beyond “Columbus” to nurture a “people’s history” curriculum — searching out those stories that help explain how this has become such a profoundly unequal world, but also how people have constantly sought greater justice. This is the work on which educators, parents, and students need to collaborate.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

This article is part of the Zinn Education Project’s If We Knew Our History series.

Published at: GOOD magazine.

© 2012 The Zinn Education Project, a project of Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn