Pedagogy of the Oppressed is one of the foundational texts in the field of critical pedagogy, which attempts to help students question and challenge domination, and the beliefs and practices that dominate.

Pedagogy of the Oppressed is one of the foundational texts in the field of critical pedagogy, which attempts to help students question and challenge domination, and the beliefs and practices that dominate.

First published in Portuguese in 1968, Pedagogy of the Oppressed was translated and published in English in 1970. Paulo Freire’s work has helped to empower countless people throughout the world and has taken on special urgency in the United States and Western Europe, where the creation of a permanent underclass among the underprivileged and minorities in cities and urban centers is ongoing.

This 50th anniversary edition includes an updated introduction by Donaldo Macedo, a new afterword by Ira Shor and interviews with Marina Aparicio Barberán, Noam Chomsky, Ramón Flecha, Gustavo Fischman, Ronald David Glass, Valerie Kinloch, Peter Mayo, Peter McLaren and Margo Okazawa-Rey to inspire a new generation of educators, students, and general readers for years to come. [Publisher’s description.]

ISBN: 9781501314131 | Bloomsbury

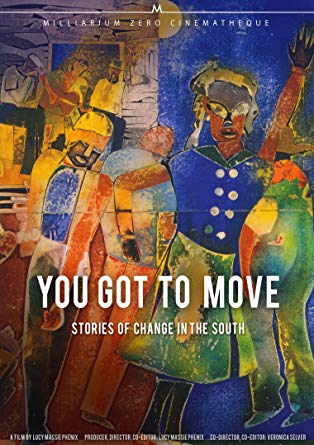

Watch this film on 9/19/2021: 5 pm Pacific / 8pm EST HotHouse FB Live: https://fb.me/e/1GG2b50kC HotHouse Twitch TV: https://www.twitch.tv/hothouseglobal

Excerpt from Pedagogy of the Oppressed

A revolutionary leadership must accordingly practice co-intentional education. Teachers and students (leadership and people), co-intent on reality, are both Subjects, not only in the task of unveiling that reality, and thereby coming to know it critically, but in the task of re-creating that knowledge. As they attain this knowledge of reality through common reflection and action, they discover themselves as its permanent re-creators. In this way, the presence of the oppressed in the struggle for their liberation will be what it should be: not pseudo-participation, but committed involvement.

. . . .A careful analysis of the teacher-student relationship at any level, inside or outside the school, reveals itself its fundamentally narrative character. This relationship involves a narrating Subject (the teacher) and patient, listening objects (the students). The contents, whether values or empirical dimensions of reality, tend in the process of being narrated to become lifeless and petrified. Education is suffering from narration sickness.

The teacher talks about reality as if it were motionless, static, compartmentalized, and predictable. Or else he expounds on a topic completely alien to the existential experience of the students. His task is to “fill” the students with the contents of his narration — contents which are detached from reality, disconnected from the totality that engendered them and could give them significance. Words are emptied of their concreteness and become a hollow, alienated, and alienating verbosity.

The outstanding characteristic of this narrative education, then, is the sonority of words, not their transforming power. “Four times four is sixteen; the capital of Pará is Belém.” The student records, memorizes, and repeats these phrases without perceiving what four times four really means, or realizing the true significance of “capital” in the affirmation “the capital of Pará is Belém,” that is, what Belém means for Pará and what Pará means for Brazil.

Narration (with the teacher as narrator) leads the students to memorize mechanically the narrated content. Worse yet, it turns them into “containers,” into “receptacles” to be “filled” by the teacher. The more completely he fills the receptacles, the better a teacher he is. The more meekly the receptacles permit themselves to be filled, the better students they are.

Education thus becomes an act of depositing, in which the students are the depositories and the teacher is the depositor. Instead of communicating, the teacher issues communiqués and makes deposits which the students patiently receive, memorize, and repeat. This is the “banking” concept of education, in which the scope of action allowed to the students extends only as far as receiving, filing, and storing the deposits. They do, it is true, have the opportunity to become collectors or cataloguers of the things they store. But in the last analysis, it is men themselves who are filed away through the lack of creativity, transformation, and knowledge in this (at best) misguided system. For apart from inquiry, apart from the praxis, men cannot be truly human. Knowledge emerges only through invention and re-invention, through the restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry men pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other.

In the banking concept of education, knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing. Projecting an absolute ignorance onto others, a characteristic of the ideology of oppression, negates education and knowledge as processes of inquiry. The teacher presents himself to his students as their necessary opposite; by considering their ignorance absolute, he justifies his own existence. The students, alienated like the slave in the Hegelian dialectic, accept their ignorance as justifying the teacher’s existence—but, unlike the slave, they never discover that they educate the teacher.

The raison d’etre of libertarian education, on the other hand, lies in its drive towards reconciliation. Education must begin with the solution of the teacher-student contradiction, by reconciling the poles of the contradiction so that both are simultaneously teachers and students.

About Paulo Freire — A brief biography from the Freire Institute

Paulo Freire was born on September 19, 1921 in Recife, Brazil. In 1947 he began work with illiterate adults in North-East Brazil and gradually evolved a method of work with which the word conscientization has been associated.

Until 1964 he was professor of history and philosophy of education in the University of Recife and in the 1960s he was involved with a popular education movement to deal with massive illiteracy. From 1962 there were widespread experiments with his method and the movement was extended under the patronage of the federal government. In 1963 – 64 there were courses for coordinators in all Brazilian states and a plan was drawn up for the establishment of 2000 cultural circles to reach 2,000,000 illiterates.

Freire was imprisoned following the 1964 coup d’etat for what the new regime considered to be subversive elements in his teaching. He next appeared in exile in Chile where his method was used and the UN School of Political Sciences held seminars on his work. In 1969—70 he was visiting professor at the Centre for the Study of Development and Social Change at Harvard University.

Myles Horton, Paulo Freire, and adult educators at Highlander, 1987.

He then went to the World Council of Churches in Geneva where, in 1970, he took up a post as special consultant in the Office of Education. Over the next nine years in that post he advised on education reform and initiated popular education activities with a range of groups.

Paulo Freire was able to return to Brazil by 1979. Freire joined the Workers’ Party in Sao Paulo and headed up its adult literacy project for six years. When the party took control of Sao Paulo municipality following elections in 1988, Paulo Freire was appointed as Sao Paulo’s Secretary of Education.

Freire died in 1997.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn