. . . This sudden outburst of student activism was, in fact, not so sudden. Over the year, Linda’s and my class focused on issues of social justice and resistance — ours was a “talk back” curriculum. We wanted students to feel themselves part of an American, even international, tradition of struggle against oppression. From Taíno Indian resistance against Columbus and Spanish colonialism, to Shays’ Rebellion of poor farmers after the American Revolution, to the Abolition movement, to our most recent unit on the U.S. labor movement, we hoped students would draw inspiration and wisdom from the past. Linda and I thought they ought to know that if they act against injustice, they’re in good company. “History is not just stories about dead people,” we told them the first day of class. “History should be of use.”

. . . This sudden outburst of student activism was, in fact, not so sudden. Over the year, Linda’s and my class focused on issues of social justice and resistance — ours was a “talk back” curriculum. We wanted students to feel themselves part of an American, even international, tradition of struggle against oppression. From Taíno Indian resistance against Columbus and Spanish colonialism, to Shays’ Rebellion of poor farmers after the American Revolution, to the Abolition movement, to our most recent unit on the U.S. labor movement, we hoped students would draw inspiration and wisdom from the past. Linda and I thought they ought to know that if they act against injustice, they’re in good company. “History is not just stories about dead people,” we told them the first day of class. “History should be of use.”

Through role plays, simulations, improvisations, class discussions, and assignments of imaginative and personal writing, we tried to encourage critical thought and student initiative.

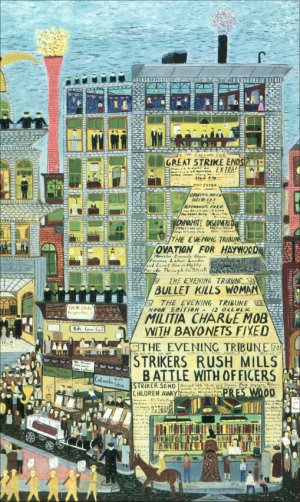

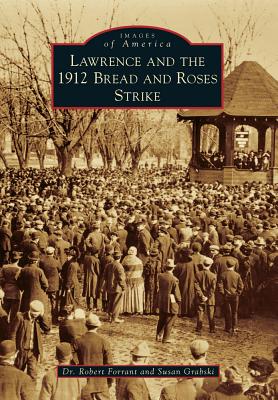

In brief, this was the pedagogical context that may have provoked students’ response to Willamette Week’s attack — not to mention that this was an extraordinarily talented, big-hearted group of young people. But a role play students had just completed on the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and the 1912 Lawrence, Massachusetts, textile strike — “the singing strike” — shaped the specific form of student actions.

Twitter

Google plus

LinkedIn